-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

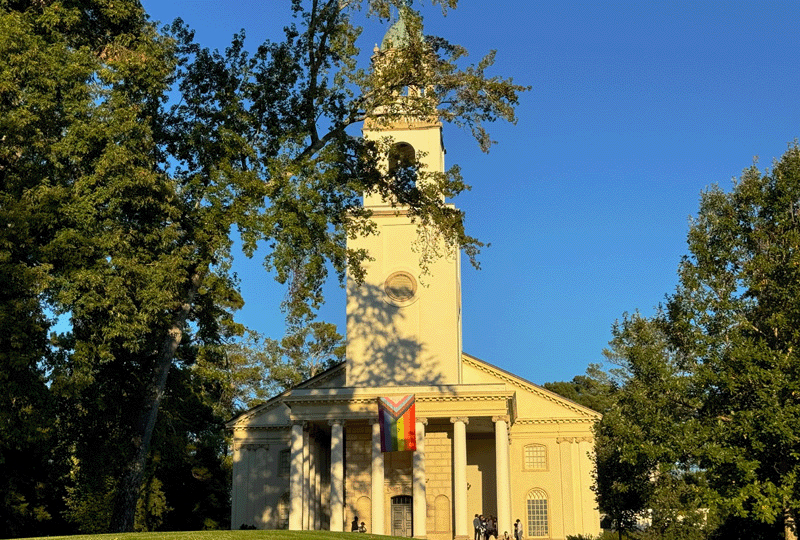

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

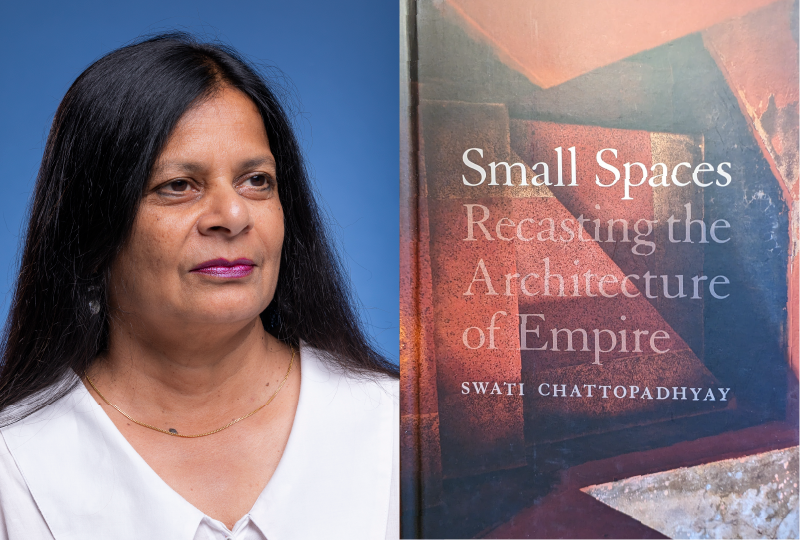

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Call for Papers: Infrastructure in Times of Crisis. Imagining and Designing Worlds That Reflect Climate Change

Proposals for completes articles should be sent by e-mail before 25 February 2025 to the Cahiers de la Recherche Architectural et Paysagere (CRAUP)’ editorial office: craup.secretariat@gmail.com For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email

France

Aude Clavel

For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email https://journals.openedition.org/craup/14806

For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email https://journals.openedition.org/craup/14806

Add to:

The dawn of the 21st century has been described as an “infrastructural turn” by many humanities and social science researchers. The spectrum of disciplines interested in “infrastructure” as a field of study has significantly increased, going beyond technological or functional dimensions to question the political, societal and cultural impacts. This break with the Prometheus myth and promises of infrastructural modernity reveal wide-ranging adversities and inadequacies whether endured or challenged.

Over the last two decades, repeated crises of various kinds (ecological, economic, energy, etc.) have continuously underlined infrastructural vulnerability, along with its strategic role (robustness) in responding to these situations through the short, medium and long term. Infrastructure has also been associated with new values, virtues and capacities, intended to contribute to a more sustainable, equitable and responsible future. Do these new “promises” create yet another type of “infrastructural turn”?

With this in mind, the present issue takes a closer look at the changing design practices of spatial discipline actors, given the infrastructural challenges sparked by crises.

Beyond movement control infrastructure

Imagining cities and territories with regard to movement (of people, goods, energy, or information), along with the changing character and speed thereof, has permeated and often dominated the history of architectural and urban production in the modern industrialized world. Physical infrastructure has fed this imagined narrative, both in terms of time and scale, by distinguishing itself as being designed and built to interconnect populated areas spatially and over time—i.e., highways, railroads, etc.—or to adapt natural environments to human activities—i.e., dykes, bridges, dams, etc. Further, their conceptualization is a long-term process, involving irregular phases that are inevitably flexible to various territorial developments and periods. As such, they must contend with contexts in which there exist factors that transcend the technical entity or system itself, constantly shifting and of a cyclical, structural, hypothetical or unknown nature. Moreover, the ever-present vision of exponential growth has rendered them devices for territorial and environmental control, giving rise to extensive systems and artifacts designed to exploit, integrate or channel these movements. Such infrastructure defines scales of intervention that challenge modern forms, whether superstructures or megastructures, in their capacity to serve societal purposes. Other infrastructure was described as a “megamachine,” according to Lewis Mumford, considered as social and political systems in social science disciplines, comparable to the technological systems in the fields of architecture and urban design. How can various disciplines reappropriate material and societal infrastructure as a field of investigation?

Crises as a Way of Rethinking the Role of Infrastructure

The ecological, economic and social crises of the early 21st century have prompted us to rethink the role of infrastructure in the movement of goods, living things, energy and information; specifically, in terms of society’s core values (i.e., eco-responsibility, energy conservation, or accessibility) and transformed considerations (i.e., coexistence of living organisms, social interaction, or health safety). As a result, designers must adapt their knowledge to the growing and shifting uncertainties of the contexts in which infrastructure is planned, as well as to the manifold pressures it faces. Characterized by their indefinite timeframes, recurrence and peaks, crises have become key concerns in many designers’ approaches. We posit that these developments are renewing infrastructural design principles and practices, especially by reintroducing narratives, imagined worlds and fictional representations into design devices. This opens up spaces for reflection and exchange with the various players involved, incorporating these crisis-specific factors and displaying them to generate greater understanding. These principles are increasingly being adopted when it comes to mobility infrastructure. In Europe, for example, researchers and designers are exploring ways in which extreme circumstances can be used to rethink urban and regional planning, founded on ideas of an “unthinkable future.” Similarly, in Japan, excessive transport networks are being challenged by the demographic crisis, leading to alternative ecological narratives depicting an immediate decreased metropolitan future. In other words, designers may once again be using probability as an operative device, to portray possible or potential future scenarios whether basic or extreme. But what about other types of infrastructure?

This call for proposals invites authors to submit articles in line with one or more of the following three themes, exploring the relationship between existing or imagined infrastructure arising from climate-related risks.

1. Exploring and representing infrastructural vulnerabilities

For urban planners and architects alike, thinking about infrastructure has involved figurative explorations of future scenarios, described as imaginary or visionary, emphasizing technical innovation, uninhibited aesthetics and even new societal models. More rarely, however, it has given rise to representations incorporating the limits and risks associated with increased and, especially, accelerated movement. Today, various crises and their aftermath have brought the topic of acceleration to the fore, along with existing pressure on mobility infrastructure and (how it affects) environments. Over the past ten years, the COVID-19 crisis and changing lifestyles have transformed the use of this infrastructure, highlighting tensions between its permanent nature versus its obsolescence. Contributions should explore the interplay between time and space, as illustrated by situations of infrastructural obsolescence, vulnerability and nuisance, leading to their dismantling in the wake of natural disasters or political decisions. Examples may include natural resource depletion, biodiversity collapse, increasing disasters (including health catastrophes), reduced mobility or, conversely, high levels of migration resulting from geopolitical conflicts. In these recurring and random situations conducive to vulnerability, do scales of time and space require new tools for reflection and systems of representation (scenario, fiction, narratives, etc.)? Expected contributions will be based on critical analyses of various kinds of infrastructural vulnerability, both historical and current, addressed through exploratory approaches and systems of representation linked to environmental issues. Contributions may also focus on technical (obsolescence, carbon impact, etc.) or reflective questions relating to vulnerability.

2. Infrastructural adaptation to risk

Since the 1960s, imagined apocalyptic societies have sought to alert and to exist, contrasting with those of a more progressive nature. Think of the ideas of architects such as Cedric Price or the Archigram group (Walking City, 1961). In the midst of the Cold War, with nuclear angst and ecological catastrophe looming on the horizon, these designers rallied an imagination radically at odds with the promise of growth, even to the point of suggesting the demise of the industrial world’s perennial infrastructure. Today, plans for infrastructural transformation, adaptation and disassembly are emerging in response to emergencies, in terms of migration, increased tourist flow and logistics. Regardless of whether they concern the creation, repair, alteration or dismantling of different forms of infrastructure (mobility, logistics, energy, ecology, etc.), do these devices present common and reproducible features? What design methodologies and forms of implementation are shared by architects, urban planners, landscape architects and actors from other disciplines? To what extent and how do the “new” fundamental values attributed to infrastructure give rise to a renewal of the design devices of architects, urban planners or landscape architects? Could forms of reversibility also be imagined to adapt to crises? In this respect, generalizations are to be expected. Based on specific case studies (contemporary infrastructure projects) that present alternate design and representation devices in time of crisis, contributions may also offer a new perspective on the history of imagined risk, as it relates to mobility infrastructure and the evolution of environmental issues.

3. Anticipating future infrastructure

Today, we must consider the role of imaginary worlds in design, as they integrate an awareness of extreme but very real phenomena, already at work. The majority of these imagined infrastructural projects have contributed to shaping representations of possible futures, applying supposedly controllable solutions to common timeframes and parameters involved in movement control, whatever they may be. Yet they have often overlooked the risk and uncertainty inherent in physical movements, whether massive or irregular, growing or shrinking, lasting or temporary. In this context, exploring imagined worlds or alternative forms of representation actively propelling infrastructural design will enable us to identify emerging practices. Which imagined worlds are at work when thinking about territorial resilience? The proliferation of risk factors and accelerating changes in infrastructural use have transformed territories and natural environments. It is now clear that climate-related extremes cannot be managed solely through new defensive infrastructure. What new forms of infrastructure will result from these situations? How does such anticipation come about? Who are the players involved, and what are the devices and forms of representation? How do they participate in renewing conceptual and possibly operational approaches to infrastructure in a more resilient environment? Does consideration of the inherent risks and uncertainties associated with emergency or extreme situations, whether real or imagined, create alternative forms of design and representation that envision a less anthropized world? Contributions should provide a critical reflection and analysis of projects that incorporate uncertainty factors as a means of anticipating future infrastructure. Examples include renewable energy (i.e., the use of waves and wind), infrastructure welcoming living organisms (i.e., biodiversity zones, restoration programs), and so on. Contributions may also feature anticipatory narratives (utopias, literature, fiction, etc.) depicting future crises and uncertainties. To what extent can anticipatory projects represent the future?

SubmissionDeadline

Proposals for full articles must be sent by email before February 25, 2025 to the editorial secretariat of the Cahiers de la recherche architecturale, urbaine et paysagère : craup.secretariat@gmail.com For more information, contact Aude Clavel at 06 10 55 11 36

Articles must not exceed 40,000 characters, including spaces.

Accepted languages: French, English.

Articles must be accompanied by:

- 1 biobibliographical notice between 5 and 10 lines (first and last name of the author(s), professional status and/or titles, possible institutional affiliation, research themes, latest publications, email address).

- 2 abstracts in French and English.

- 5 keywords in French and English.

- The title must appear in French and English.

Row White

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row BG Green

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row Gray

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row Green

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row CP Dark

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 1

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 2

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 3

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 4

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 5

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

lead

Blockquote: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

Two Buttons in one paragraph

Expandable List

At the center of SAH Celebrates is the Charnley-Persky House (1891–1892), a National Historic Landmark and a Chicago Landmark designed by Louis Sullivan with assistance from Frank Lloyd Wright, that serves as SAH headquarters. SAH Celebrates highlights the importance of fostering a supportive community whose efforts ensure the stewardship of architectural gems like the Charnley-Persky House.

Proceeds benefit the ongoing maintenance and care of the Charnley-Persky House and SAH's educational programs and publications, including SAH Archipedia and Buildings of the United States.

T. Gunny Harboe, FAIA

Founder, Harboe Architects

Michelangelo Sabatino, PhD

Professor, Director of Ph.D. Program in Architecture, Inaugural John Vinci Distinguished Research Fellow, Illinois Institute of Technology

Founder, Harboe Architects

Michelangelo Sabatino, PhD

Professor, Director of Ph.D. Program in Architecture, Inaugural John Vinci Distinguished Research Fellow, Illinois Institute of Technology

Laurence O. Booth, FAIA

Booth Hansen Architects

Rebekah Coffman

Chicago History Museum

Stuart Cohen, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Thomas M. Dietz

Alison Fisher

Art Institute of Chicago

Scott Fortman

Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, Chicago-Midwest Chapter

Keith Goad

The Keith Goad Group, Berkshire Hathaway Home Services Chicago

Chandra Goldsmith

IIT CoA Board of Advisors

Barbara Gordon

Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

Eleanor Gorski

Chicago Architecture Center

Stuart Graff

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Julie Hacker, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Sarah Herda

Graham Foundation

Harry Hunderman, FAIA

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc

Lisa Key

Driehaus Museum

Nancy and Thomas Klein

SAH Chicago Chapter

Thomas Leslie

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Jen Masengarb

AIA Chicago

Bonnie McDonald

Landmarks Illinois

Justin Miller

Docomomo US/Chicago

Ward Miller

Preservation Chicago

Heather Hyde Minor

University of Notre Dame

Keith N. Morgan, FSAH

SAH Past President

Sarah Rogers Morris

University of Illinois at Chicago

John K. Notz Jr.

SAH Benefactor Member

Keith Olsen

Olsen Vranas Architects

Abby Persky

Chicago, IL

Laurie Petersen

Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Charlie Pipal

School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Deborah Slaton

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Assocites, Inc.

Cynthia Vranas

Mies Van der Rohe Society

Cynthia Weese, FAIA

Weese, Langley, Weese Architects and Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Ernie Wong

Commission on Chicago Landmarks

Booth Hansen Architects

Rebekah Coffman

Chicago History Museum

Stuart Cohen, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Thomas M. Dietz

Jaeger Nickola Kuhlman & Associates

Art Institute of Chicago

Scott Fortman

Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, Chicago-Midwest Chapter

Keith Goad

The Keith Goad Group, Berkshire Hathaway Home Services Chicago

Chandra Goldsmith

IIT CoA Board of Advisors

Barbara Gordon

Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

Eleanor Gorski

Chicago Architecture Center

Stuart Graff

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Julie Hacker, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Sarah Herda

Graham Foundation

Harry Hunderman, FAIA

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc

Lisa Key

Driehaus Museum

Nancy and Thomas Klein

SAH Chicago Chapter

Thomas Leslie

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Jen Masengarb

AIA Chicago

Bonnie McDonald

Landmarks Illinois

Justin Miller

Docomomo US/Chicago

Ward Miller

Preservation Chicago

Heather Hyde Minor

University of Notre Dame

Keith N. Morgan, FSAH

SAH Past President

Sarah Rogers Morris

University of Illinois at Chicago

John K. Notz Jr.

SAH Benefactor Member

Keith Olsen

Olsen Vranas Architects

Abby Persky

Chicago, IL

Laurie Petersen

Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Charlie Pipal

School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Deborah Slaton

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Assocites, Inc.

Chris-Annmarie Spencer, AIA, NOMA

AIA Chicago Foundation

Cynthia Vranas

Mies Van der Rohe Society

Cynthia Weese, FAIA

Weese, Langley, Weese Architects and Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Ernie Wong

Commission on Chicago Landmarks

Download the prospectus for information about sponsorship and advertising opportunities. Please contact Ben Thomas at 312-573-1365 if you have questions.

Category Dropdown

OOTB Cards

Card

Card.Alt

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card.Simple

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card.Hero

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card ButtonCustom Cards

List.Custom Card

List.Custom Card 2 Column

List.Custom Card 3 Column

List.Custom Card 4 Column

Detail.Card

Detail.Card Alt

Annual Conference Fellowships

Conference fellowships support session chairs and speakers participating in the SAH Annual International Conference.

Detail.Card Simple

Another Card Title With Extra Text

This is a card summary. Has a limit of 255 characters. We can increase that if you think we need more text.

Detail.Card Hero

Content Types

Blogs

Blog List

Events

Events List

Call for Papers: Infrastructure in Times of Crisis. Imagining and Designing Worlds That Reflect Climate Change

Proposals for completes articles should be sent by e-mail before 25 February 2025 to the Cahiers de la Recherche Architectural et Paysagere (CRAUP)’ editorial office: craup.secretariat@gmail.com For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email

France

Aude Clavel

For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email https://journals.openedition.org/craup/14806

For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email https://journals.openedition.org/craup/14806

Add to:

The dawn of the 21st century has been described as an “infrastructural turn” by many humanities and social science researchers. The spectrum of disciplines interested in “infrastructure” as a field of study has significantly increased, going beyond technological or functional dimensions to question the political, societal and cultural impacts. This break with the Prometheus myth and promises of infrastructural modernity reveal wide-ranging adversities and inadequacies whether endured or challenged.

Over the last two decades, repeated crises of various kinds (ecological, economic, energy, etc.) have continuously underlined infrastructural vulnerability, along with its strategic role (robustness) in responding to these situations through the short, medium and long term. Infrastructure has also been associated with new values, virtues and capacities, intended to contribute to a more sustainable, equitable and responsible future. Do these new “promises” create yet another type of “infrastructural turn”?

With this in mind, the present issue takes a closer look at the changing design practices of spatial discipline actors, given the infrastructural challenges sparked by crises.

Beyond movement control infrastructure

Imagining cities and territories with regard to movement (of people, goods, energy, or information), along with the changing character and speed thereof, has permeated and often dominated the history of architectural and urban production in the modern industrialized world. Physical infrastructure has fed this imagined narrative, both in terms of time and scale, by distinguishing itself as being designed and built to interconnect populated areas spatially and over time—i.e., highways, railroads, etc.—or to adapt natural environments to human activities—i.e., dykes, bridges, dams, etc. Further, their conceptualization is a long-term process, involving irregular phases that are inevitably flexible to various territorial developments and periods. As such, they must contend with contexts in which there exist factors that transcend the technical entity or system itself, constantly shifting and of a cyclical, structural, hypothetical or unknown nature. Moreover, the ever-present vision of exponential growth has rendered them devices for territorial and environmental control, giving rise to extensive systems and artifacts designed to exploit, integrate or channel these movements. Such infrastructure defines scales of intervention that challenge modern forms, whether superstructures or megastructures, in their capacity to serve societal purposes. Other infrastructure was described as a “megamachine,” according to Lewis Mumford, considered as social and political systems in social science disciplines, comparable to the technological systems in the fields of architecture and urban design. How can various disciplines reappropriate material and societal infrastructure as a field of investigation?

Crises as a Way of Rethinking the Role of Infrastructure

The ecological, economic and social crises of the early 21st century have prompted us to rethink the role of infrastructure in the movement of goods, living things, energy and information; specifically, in terms of society’s core values (i.e., eco-responsibility, energy conservation, or accessibility) and transformed considerations (i.e., coexistence of living organisms, social interaction, or health safety). As a result, designers must adapt their knowledge to the growing and shifting uncertainties of the contexts in which infrastructure is planned, as well as to the manifold pressures it faces. Characterized by their indefinite timeframes, recurrence and peaks, crises have become key concerns in many designers’ approaches. We posit that these developments are renewing infrastructural design principles and practices, especially by reintroducing narratives, imagined worlds and fictional representations into design devices. This opens up spaces for reflection and exchange with the various players involved, incorporating these crisis-specific factors and displaying them to generate greater understanding. These principles are increasingly being adopted when it comes to mobility infrastructure. In Europe, for example, researchers and designers are exploring ways in which extreme circumstances can be used to rethink urban and regional planning, founded on ideas of an “unthinkable future.” Similarly, in Japan, excessive transport networks are being challenged by the demographic crisis, leading to alternative ecological narratives depicting an immediate decreased metropolitan future. In other words, designers may once again be using probability as an operative device, to portray possible or potential future scenarios whether basic or extreme. But what about other types of infrastructure?

This call for proposals invites authors to submit articles in line with one or more of the following three themes, exploring the relationship between existing or imagined infrastructure arising from climate-related risks.

1. Exploring and representing infrastructural vulnerabilities

For urban planners and architects alike, thinking about infrastructure has involved figurative explorations of future scenarios, described as imaginary or visionary, emphasizing technical innovation, uninhibited aesthetics and even new societal models. More rarely, however, it has given rise to representations incorporating the limits and risks associated with increased and, especially, accelerated movement. Today, various crises and their aftermath have brought the topic of acceleration to the fore, along with existing pressure on mobility infrastructure and (how it affects) environments. Over the past ten years, the COVID-19 crisis and changing lifestyles have transformed the use of this infrastructure, highlighting tensions between its permanent nature versus its obsolescence. Contributions should explore the interplay between time and space, as illustrated by situations of infrastructural obsolescence, vulnerability and nuisance, leading to their dismantling in the wake of natural disasters or political decisions. Examples may include natural resource depletion, biodiversity collapse, increasing disasters (including health catastrophes), reduced mobility or, conversely, high levels of migration resulting from geopolitical conflicts. In these recurring and random situations conducive to vulnerability, do scales of time and space require new tools for reflection and systems of representation (scenario, fiction, narratives, etc.)? Expected contributions will be based on critical analyses of various kinds of infrastructural vulnerability, both historical and current, addressed through exploratory approaches and systems of representation linked to environmental issues. Contributions may also focus on technical (obsolescence, carbon impact, etc.) or reflective questions relating to vulnerability.

2. Infrastructural adaptation to risk

Since the 1960s, imagined apocalyptic societies have sought to alert and to exist, contrasting with those of a more progressive nature. Think of the ideas of architects such as Cedric Price or the Archigram group (Walking City, 1961). In the midst of the Cold War, with nuclear angst and ecological catastrophe looming on the horizon, these designers rallied an imagination radically at odds with the promise of growth, even to the point of suggesting the demise of the industrial world’s perennial infrastructure. Today, plans for infrastructural transformation, adaptation and disassembly are emerging in response to emergencies, in terms of migration, increased tourist flow and logistics. Regardless of whether they concern the creation, repair, alteration or dismantling of different forms of infrastructure (mobility, logistics, energy, ecology, etc.), do these devices present common and reproducible features? What design methodologies and forms of implementation are shared by architects, urban planners, landscape architects and actors from other disciplines? To what extent and how do the “new” fundamental values attributed to infrastructure give rise to a renewal of the design devices of architects, urban planners or landscape architects? Could forms of reversibility also be imagined to adapt to crises? In this respect, generalizations are to be expected. Based on specific case studies (contemporary infrastructure projects) that present alternate design and representation devices in time of crisis, contributions may also offer a new perspective on the history of imagined risk, as it relates to mobility infrastructure and the evolution of environmental issues.

3. Anticipating future infrastructure

Today, we must consider the role of imaginary worlds in design, as they integrate an awareness of extreme but very real phenomena, already at work. The majority of these imagined infrastructural projects have contributed to shaping representations of possible futures, applying supposedly controllable solutions to common timeframes and parameters involved in movement control, whatever they may be. Yet they have often overlooked the risk and uncertainty inherent in physical movements, whether massive or irregular, growing or shrinking, lasting or temporary. In this context, exploring imagined worlds or alternative forms of representation actively propelling infrastructural design will enable us to identify emerging practices. Which imagined worlds are at work when thinking about territorial resilience? The proliferation of risk factors and accelerating changes in infrastructural use have transformed territories and natural environments. It is now clear that climate-related extremes cannot be managed solely through new defensive infrastructure. What new forms of infrastructure will result from these situations? How does such anticipation come about? Who are the players involved, and what are the devices and forms of representation? How do they participate in renewing conceptual and possibly operational approaches to infrastructure in a more resilient environment? Does consideration of the inherent risks and uncertainties associated with emergency or extreme situations, whether real or imagined, create alternative forms of design and representation that envision a less anthropized world? Contributions should provide a critical reflection and analysis of projects that incorporate uncertainty factors as a means of anticipating future infrastructure. Examples include renewable energy (i.e., the use of waves and wind), infrastructure welcoming living organisms (i.e., biodiversity zones, restoration programs), and so on. Contributions may also feature anticipatory narratives (utopias, literature, fiction, etc.) depicting future crises and uncertainties. To what extent can anticipatory projects represent the future?

SubmissionDeadline

Proposals for full articles must be sent by email before February 25, 2025 to the editorial secretariat of the Cahiers de la recherche architecturale, urbaine et paysagère : craup.secretariat@gmail.com For more information, contact Aude Clavel at 06 10 55 11 36

Articles must not exceed 40,000 characters, including spaces.

Accepted languages: French, English.

Articles must be accompanied by:

- 1 biobibliographical notice between 5 and 10 lines (first and last name of the author(s), professional status and/or titles, possible institutional affiliation, research themes, latest publications, email address).

- 2 abstracts in French and English.

- 5 keywords in French and English.

- The title must appear in French and English.

Events Home Blocks

Call for Papers: Infrastructure in Times of Crisis. Imagining and Designing Worlds That Reflect Climate Change

Proposals for completes articles should be sent by e-mail before 25 February 2025 to the Cahiers de la Recherche Architectural et Paysagere (CRAUP)’ editorial office: craup.secretariat@gmail.com For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email

France

Aude Clavel

For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email https://journals.openedition.org/craup/14806

For more information, contact Aude Clavel on 06 10 55 11 36 or by email https://journals.openedition.org/craup/14806

Add to:

The dawn of the 21st century has been described as an “infrastructural turn” by many humanities and social science researchers. The spectrum of disciplines interested in “infrastructure” as a field of study has significantly increased, going beyond technological or functional dimensions to question the political, societal and cultural impacts. This break with the Prometheus myth and promises of infrastructural modernity reveal wide-ranging adversities and inadequacies whether endured or challenged.

Over the last two decades, repeated crises of various kinds (ecological, economic, energy, etc.) have continuously underlined infrastructural vulnerability, along with its strategic role (robustness) in responding to these situations through the short, medium and long term. Infrastructure has also been associated with new values, virtues and capacities, intended to contribute to a more sustainable, equitable and responsible future. Do these new “promises” create yet another type of “infrastructural turn”?

With this in mind, the present issue takes a closer look at the changing design practices of spatial discipline actors, given the infrastructural challenges sparked by crises.

Beyond movement control infrastructure

Imagining cities and territories with regard to movement (of people, goods, energy, or information), along with the changing character and speed thereof, has permeated and often dominated the history of architectural and urban production in the modern industrialized world. Physical infrastructure has fed this imagined narrative, both in terms of time and scale, by distinguishing itself as being designed and built to interconnect populated areas spatially and over time—i.e., highways, railroads, etc.—or to adapt natural environments to human activities—i.e., dykes, bridges, dams, etc. Further, their conceptualization is a long-term process, involving irregular phases that are inevitably flexible to various territorial developments and periods. As such, they must contend with contexts in which there exist factors that transcend the technical entity or system itself, constantly shifting and of a cyclical, structural, hypothetical or unknown nature. Moreover, the ever-present vision of exponential growth has rendered them devices for territorial and environmental control, giving rise to extensive systems and artifacts designed to exploit, integrate or channel these movements. Such infrastructure defines scales of intervention that challenge modern forms, whether superstructures or megastructures, in their capacity to serve societal purposes. Other infrastructure was described as a “megamachine,” according to Lewis Mumford, considered as social and political systems in social science disciplines, comparable to the technological systems in the fields of architecture and urban design. How can various disciplines reappropriate material and societal infrastructure as a field of investigation?

Crises as a Way of Rethinking the Role of Infrastructure

The ecological, economic and social crises of the early 21st century have prompted us to rethink the role of infrastructure in the movement of goods, living things, energy and information; specifically, in terms of society’s core values (i.e., eco-responsibility, energy conservation, or accessibility) and transformed considerations (i.e., coexistence of living organisms, social interaction, or health safety). As a result, designers must adapt their knowledge to the growing and shifting uncertainties of the contexts in which infrastructure is planned, as well as to the manifold pressures it faces. Characterized by their indefinite timeframes, recurrence and peaks, crises have become key concerns in many designers’ approaches. We posit that these developments are renewing infrastructural design principles and practices, especially by reintroducing narratives, imagined worlds and fictional representations into design devices. This opens up spaces for reflection and exchange with the various players involved, incorporating these crisis-specific factors and displaying them to generate greater understanding. These principles are increasingly being adopted when it comes to mobility infrastructure. In Europe, for example, researchers and designers are exploring ways in which extreme circumstances can be used to rethink urban and regional planning, founded on ideas of an “unthinkable future.” Similarly, in Japan, excessive transport networks are being challenged by the demographic crisis, leading to alternative ecological narratives depicting an immediate decreased metropolitan future. In other words, designers may once again be using probability as an operative device, to portray possible or potential future scenarios whether basic or extreme. But what about other types of infrastructure?

This call for proposals invites authors to submit articles in line with one or more of the following three themes, exploring the relationship between existing or imagined infrastructure arising from climate-related risks.

1. Exploring and representing infrastructural vulnerabilities

For urban planners and architects alike, thinking about infrastructure has involved figurative explorations of future scenarios, described as imaginary or visionary, emphasizing technical innovation, uninhibited aesthetics and even new societal models. More rarely, however, it has given rise to representations incorporating the limits and risks associated with increased and, especially, accelerated movement. Today, various crises and their aftermath have brought the topic of acceleration to the fore, along with existing pressure on mobility infrastructure and (how it affects) environments. Over the past ten years, the COVID-19 crisis and changing lifestyles have transformed the use of this infrastructure, highlighting tensions between its permanent nature versus its obsolescence. Contributions should explore the interplay between time and space, as illustrated by situations of infrastructural obsolescence, vulnerability and nuisance, leading to their dismantling in the wake of natural disasters or political decisions. Examples may include natural resource depletion, biodiversity collapse, increasing disasters (including health catastrophes), reduced mobility or, conversely, high levels of migration resulting from geopolitical conflicts. In these recurring and random situations conducive to vulnerability, do scales of time and space require new tools for reflection and systems of representation (scenario, fiction, narratives, etc.)? Expected contributions will be based on critical analyses of various kinds of infrastructural vulnerability, both historical and current, addressed through exploratory approaches and systems of representation linked to environmental issues. Contributions may also focus on technical (obsolescence, carbon impact, etc.) or reflective questions relating to vulnerability.

2. Infrastructural adaptation to risk

Since the 1960s, imagined apocalyptic societies have sought to alert and to exist, contrasting with those of a more progressive nature. Think of the ideas of architects such as Cedric Price or the Archigram group (Walking City, 1961). In the midst of the Cold War, with nuclear angst and ecological catastrophe looming on the horizon, these designers rallied an imagination radically at odds with the promise of growth, even to the point of suggesting the demise of the industrial world’s perennial infrastructure. Today, plans for infrastructural transformation, adaptation and disassembly are emerging in response to emergencies, in terms of migration, increased tourist flow and logistics. Regardless of whether they concern the creation, repair, alteration or dismantling of different forms of infrastructure (mobility, logistics, energy, ecology, etc.), do these devices present common and reproducible features? What design methodologies and forms of implementation are shared by architects, urban planners, landscape architects and actors from other disciplines? To what extent and how do the “new” fundamental values attributed to infrastructure give rise to a renewal of the design devices of architects, urban planners or landscape architects? Could forms of reversibility also be imagined to adapt to crises? In this respect, generalizations are to be expected. Based on specific case studies (contemporary infrastructure projects) that present alternate design and representation devices in time of crisis, contributions may also offer a new perspective on the history of imagined risk, as it relates to mobility infrastructure and the evolution of environmental issues.

3. Anticipating future infrastructure

Today, we must consider the role of imaginary worlds in design, as they integrate an awareness of extreme but very real phenomena, already at work. The majority of these imagined infrastructural projects have contributed to shaping representations of possible futures, applying supposedly controllable solutions to common timeframes and parameters involved in movement control, whatever they may be. Yet they have often overlooked the risk and uncertainty inherent in physical movements, whether massive or irregular, growing or shrinking, lasting or temporary. In this context, exploring imagined worlds or alternative forms of representation actively propelling infrastructural design will enable us to identify emerging practices. Which imagined worlds are at work when thinking about territorial resilience? The proliferation of risk factors and accelerating changes in infrastructural use have transformed territories and natural environments. It is now clear that climate-related extremes cannot be managed solely through new defensive infrastructure. What new forms of infrastructure will result from these situations? How does such anticipation come about? Who are the players involved, and what are the devices and forms of representation? How do they participate in renewing conceptual and possibly operational approaches to infrastructure in a more resilient environment? Does consideration of the inherent risks and uncertainties associated with emergency or extreme situations, whether real or imagined, create alternative forms of design and representation that envision a less anthropized world? Contributions should provide a critical reflection and analysis of projects that incorporate uncertainty factors as a means of anticipating future infrastructure. Examples include renewable energy (i.e., the use of waves and wind), infrastructure welcoming living organisms (i.e., biodiversity zones, restoration programs), and so on. Contributions may also feature anticipatory narratives (utopias, literature, fiction, etc.) depicting future crises and uncertainties. To what extent can anticipatory projects represent the future?

SubmissionDeadline

Proposals for full articles must be sent by email before February 25, 2025 to the editorial secretariat of the Cahiers de la recherche architecturale, urbaine et paysagère : craup.secretariat@gmail.com For more information, contact Aude Clavel at 06 10 55 11 36

Articles must not exceed 40,000 characters, including spaces.

Accepted languages: French, English.

Articles must be accompanied by:

- 1 biobibliographical notice between 5 and 10 lines (first and last name of the author(s), professional status and/or titles, possible institutional affiliation, research themes, latest publications, email address).

- 2 abstracts in French and English.

- 5 keywords in French and English.

- The title must appear in French and English.