-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

SAH Archipedia Highlights: Native American Heritage Month

Oct 31, 2023

by

SAH News

In celebration of Native American Heritage Month and the formation of the SAH Indigenous Architecture Affiliate Group, below is a selection of SAH Archipedia content highlighting the contributions of Native American architects. Additionally, a thematic essay on Gulf Coast Tribes explores the building activities of the Calusa, the Apalachee, the Chitimacha, and the Karankawa along a shared body of water. This essay was written by the 2017 Charles E. Peterson Fellow, Willa Granger. Applications for the 2024 Peterson Fellowship are currently open to graduate students until December 31, 2023.

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution

Photograph by Carol Highsmith

The siting of the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall is significant, particularly the building's confrontational engagement with the Capitol building, a form of acknowledgment and contempt for federally supported genocides of Native peoples throughout the nation's history. Prior to the design of the structure, the Museum engaged in a three-year dialogue with Native communities in the United States, Canada, and Mexico to develop a guiding document, "The Way of the People," which shaped the design of the building. One of the most important goals was to highlight that Native communities were not restricted to their anthropological pasts, but instead were alive and active. The museum hired a collaborative group of Native American architects—Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot), Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee/Choctaw), Donna House (Dine/Oneida), and Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi)—to design a building that contrasted neighboring cultural institutions. Most obviously, the building does not follow the modernist and classical forms of the other Smithsonian museums. Even in orientation, the National Museum of the American Indian incorporates Native customs by facing east toward the rising sun. Architecturally, the building’s distinctive curvilinear form evokes a wind-sculpted rock formation not unlike those of the Medicine Rocks in Montana. The five-story structure is clad in golden-toned Kasota stone, a dolomitic limestone from Minnesota. READ MORE

Bosque Redondo Memorial

Courtesy of the Friends of the Bosque Redondo Memorial

The Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner State Monument commemorates the site where thousands of Mescalero Apache and Navajo people were imprisoned between 1862 and 1868. The journey to Bosque Redondo, now known as “The Long Walk,” and the subsequent hardships internment imposed were devastating. Of the 11,000 Navajo (Diné) who departed for Bosque Redondo beginning in 1864, only 6,800 returned in 1868. Bosque Redondo translates from the Spanish as “circular grove of trees.” This inspired architects David Sloan (Diné) and Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee-Choctaw) to design the memorial as a ring of cottonwoods with a visitor center wedged into its northwest side. The arrangement of the trees includes two openings with sightlines toward the Mescalero and Diné homelands. The restoration of the Pecos River watershed along the western edge of the circle offers an exemplary site for teaching the importance of conserving the land. READ MORE

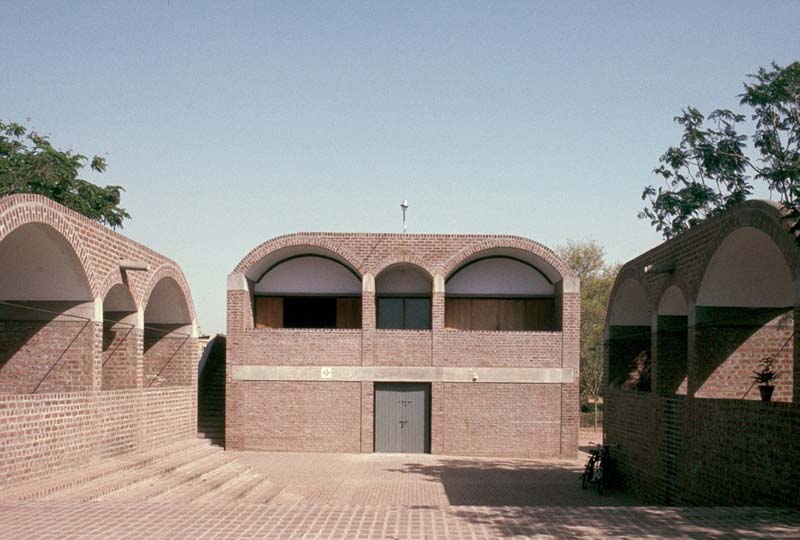

Four Winds High School

Photograph by Steve C. Martens

Working closely with the tribal council, Native American architects from three tribal nations collaborated on the design of this school in Fort Totten, North Dakota. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) design review committee, comprised mainly of Euro-Americans, was reluctant to accept a circular building because of concerns for the cost of such an unorthodox geometric configuration. The local tribal council and Native American architects for the building regarded the unifying tradition of the circle and practical space planning as compatible goals. As constructed, the plan is circular, except for a rectangular extension that contains the gymnasium. Corridors lead from entrances at the four cardinal points to the central space where there is a symbolic eagle enclosure that controls light and sound. In the interest of energy conservation, the school’s exterior has no windows, but desirable daylight is admitted through skylights, and the walls are bermed into the site. Surrounded by Enemy designed vertical concrete signposts at each entrance that are ornamented by abstract representations of an animal or natural spirit (buffalo, bird, elk, and thunder) associated with the cardinal directions. An overall design objective was to increase consciousness and pride in cultural traditions among students attending the school. READ MORE

Gulf Coast Tribes

Mound K, Crystal River Archaeological State Park, Florida. Photograph by Steven Martin

Scholars often subdivide the study of Native American culture into vast, multistate regions, including the Northeast, the Plains, and the Southwest, to name a few. The Southeast represents a zone bounded by present-day Texas, Missouri, Georgia, and Florida. This swath is expansive, and covers multiple environmental geographies: from the tropical tip of the Florida Keys to the Ozark Highlands. A quick survey of Native American building typologies from this region is equally expansive, and includes the famous earthen mounds of Cahokia in Illinois as well as the post-and-lintel chickee huts of the Seminoles in Florida. Honing this scope even further, however, we can examine a series of tribes with a major geographic commonality: the Gulf Coast. Many tribes settled along this slow arch of coastline, inhabiting land that today stretches from Florida to Texas; a selection of these groups, moving east to west, included the Calusa, the Apalachee, the Chitimacha, and the Karankawa. READ MORE

Row White

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row BG Green

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row Gray

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row Green

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Row CP Dark

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 1

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 2

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 3

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 4

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 5

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

lead

Blockquote: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

- List Item

Two Buttons in one paragraph

Expandable List

At the center of SAH Celebrates is the Charnley-Persky House (1891–1892), a National Historic Landmark and a Chicago Landmark designed by Louis Sullivan with assistance from Frank Lloyd Wright, that serves as SAH headquarters. SAH Celebrates highlights the importance of fostering a supportive community whose efforts ensure the stewardship of architectural gems like the Charnley-Persky House.

Proceeds benefit the ongoing maintenance and care of the Charnley-Persky House and SAH's educational programs and publications, including SAH Archipedia and Buildings of the United States.

T. Gunny Harboe, FAIA

Founder, Harboe Architects

Michelangelo Sabatino, PhD

Professor, Director of Ph.D. Program in Architecture, Inaugural John Vinci Distinguished Research Fellow, Illinois Institute of Technology

Founder, Harboe Architects

Michelangelo Sabatino, PhD

Professor, Director of Ph.D. Program in Architecture, Inaugural John Vinci Distinguished Research Fellow, Illinois Institute of Technology

Laurence O. Booth, FAIA

Booth Hansen Architects

Rebekah Coffman

Chicago History Museum

Stuart Cohen, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Thomas M. Dietz

Alison Fisher

Art Institute of Chicago

Scott Fortman

Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, Chicago-Midwest Chapter

Keith Goad

The Keith Goad Group, Berkshire Hathaway Home Services Chicago

Chandra Goldsmith

IIT CoA Board of Advisors

Barbara Gordon

Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

Eleanor Gorski

Chicago Architecture Center

Stuart Graff

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Julie Hacker, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Sarah Herda

Graham Foundation

Harry Hunderman, FAIA

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc

Lisa Key

Driehaus Museum

Nancy and Thomas Klein

SAH Chicago Chapter

Thomas Leslie

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Jen Masengarb

AIA Chicago

Bonnie McDonald

Landmarks Illinois

Justin Miller

Docomomo US/Chicago

Ward Miller

Preservation Chicago

Heather Hyde Minor

University of Notre Dame

Keith N. Morgan, FSAH

SAH Past President

Sarah Rogers Morris

University of Illinois at Chicago

John K. Notz Jr.

SAH Benefactor Member

Keith Olsen

Olsen Vranas Architects

Abby Persky

Chicago, IL

Laurie Petersen

Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Charlie Pipal

School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Deborah Slaton

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Assocites, Inc.

Cynthia Vranas

Mies Van der Rohe Society

Cynthia Weese, FAIA

Weese, Langley, Weese Architects and Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Ernie Wong

Commission on Chicago Landmarks

Booth Hansen Architects

Rebekah Coffman

Chicago History Museum

Stuart Cohen, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Thomas M. Dietz

Jaeger Nickola Kuhlman & Associates

Art Institute of Chicago

Scott Fortman

Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, Chicago-Midwest Chapter

Keith Goad

The Keith Goad Group, Berkshire Hathaway Home Services Chicago

Chandra Goldsmith

IIT CoA Board of Advisors

Barbara Gordon

Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

Eleanor Gorski

Chicago Architecture Center

Stuart Graff

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Julie Hacker, FAIA

Cohen-Hacker Architects

Sarah Herda

Graham Foundation

Harry Hunderman, FAIA

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc

Lisa Key

Driehaus Museum

Nancy and Thomas Klein

SAH Chicago Chapter

Thomas Leslie

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Jen Masengarb

AIA Chicago

Bonnie McDonald

Landmarks Illinois

Justin Miller

Docomomo US/Chicago

Ward Miller

Preservation Chicago

Heather Hyde Minor

University of Notre Dame

Keith N. Morgan, FSAH

SAH Past President

Sarah Rogers Morris

University of Illinois at Chicago

John K. Notz Jr.

SAH Benefactor Member

Keith Olsen

Olsen Vranas Architects

Abby Persky

Chicago, IL

Laurie Petersen

Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Charlie Pipal

School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Deborah Slaton

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Assocites, Inc.

Chris-Annmarie Spencer, AIA, NOMA

AIA Chicago Foundation

Cynthia Vranas

Mies Van der Rohe Society

Cynthia Weese, FAIA

Weese, Langley, Weese Architects and Charnley-Persky House Board Member

Ernie Wong

Commission on Chicago Landmarks

Download the prospectus for information about sponsorship and advertising opportunities. Please contact Ben Thomas at 312-573-1365 if you have questions.

Category Dropdown

OOTB Cards

Card

Card.Alt

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card.Simple

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card.Hero

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card Title

Card Text - Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Card ButtonCustom Cards

List.Custom Card

List.Custom Card 2 Column

List.Custom Card 3 Column

List.Custom Card 4 Column

Detail.Card

Detail.Card Alt

Annual Conference Fellowships

Conference fellowships support session chairs and speakers participating in the SAH Annual International Conference.

Detail.Card Simple

Another Card Title With Extra Text

This is a card summary. Has a limit of 255 characters. We can increase that if you think we need more text.

Detail.Card Hero

Content Types

Blogs

Blog List

Events

Events List

Events Home Blocks

News

News List

SAH Archipedia Highlights: Native American Heritage Month

Oct 31, 2023

by

SAH News

In celebration of Native American Heritage Month and the formation of the SAH Indigenous Architecture Affiliate Group, below is a selection of SAH Archipedia content highlighting the contributions of Native American architects. Additionally, a thematic essay on Gulf Coast Tribes explores the building activities of the Calusa, the Apalachee, the Chitimacha, and the Karankawa along a shared body of water. This essay was written by the 2017 Charles E. Peterson Fellow, Willa Granger. Applications for the 2024 Peterson Fellowship are currently open to graduate students until December 31, 2023.

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution

Photograph by Carol Highsmith

The siting of the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall is significant, particularly the building's confrontational engagement with the Capitol building, a form of acknowledgment and contempt for federally supported genocides of Native peoples throughout the nation's history. Prior to the design of the structure, the Museum engaged in a three-year dialogue with Native communities in the United States, Canada, and Mexico to develop a guiding document, "The Way of the People," which shaped the design of the building. One of the most important goals was to highlight that Native communities were not restricted to their anthropological pasts, but instead were alive and active. The museum hired a collaborative group of Native American architects—Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot), Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee/Choctaw), Donna House (Dine/Oneida), and Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi)—to design a building that contrasted neighboring cultural institutions. Most obviously, the building does not follow the modernist and classical forms of the other Smithsonian museums. Even in orientation, the National Museum of the American Indian incorporates Native customs by facing east toward the rising sun. Architecturally, the building’s distinctive curvilinear form evokes a wind-sculpted rock formation not unlike those of the Medicine Rocks in Montana. The five-story structure is clad in golden-toned Kasota stone, a dolomitic limestone from Minnesota. READ MORE

Bosque Redondo Memorial

Courtesy of the Friends of the Bosque Redondo Memorial

The Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner State Monument commemorates the site where thousands of Mescalero Apache and Navajo people were imprisoned between 1862 and 1868. The journey to Bosque Redondo, now known as “The Long Walk,” and the subsequent hardships internment imposed were devastating. Of the 11,000 Navajo (Diné) who departed for Bosque Redondo beginning in 1864, only 6,800 returned in 1868. Bosque Redondo translates from the Spanish as “circular grove of trees.” This inspired architects David Sloan (Diné) and Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee-Choctaw) to design the memorial as a ring of cottonwoods with a visitor center wedged into its northwest side. The arrangement of the trees includes two openings with sightlines toward the Mescalero and Diné homelands. The restoration of the Pecos River watershed along the western edge of the circle offers an exemplary site for teaching the importance of conserving the land. READ MORE

Four Winds High School

Photograph by Steve C. Martens

Working closely with the tribal council, Native American architects from three tribal nations collaborated on the design of this school in Fort Totten, North Dakota. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) design review committee, comprised mainly of Euro-Americans, was reluctant to accept a circular building because of concerns for the cost of such an unorthodox geometric configuration. The local tribal council and Native American architects for the building regarded the unifying tradition of the circle and practical space planning as compatible goals. As constructed, the plan is circular, except for a rectangular extension that contains the gymnasium. Corridors lead from entrances at the four cardinal points to the central space where there is a symbolic eagle enclosure that controls light and sound. In the interest of energy conservation, the school’s exterior has no windows, but desirable daylight is admitted through skylights, and the walls are bermed into the site. Surrounded by Enemy designed vertical concrete signposts at each entrance that are ornamented by abstract representations of an animal or natural spirit (buffalo, bird, elk, and thunder) associated with the cardinal directions. An overall design objective was to increase consciousness and pride in cultural traditions among students attending the school. READ MORE

Gulf Coast Tribes

Mound K, Crystal River Archaeological State Park, Florida. Photograph by Steven Martin

Scholars often subdivide the study of Native American culture into vast, multistate regions, including the Northeast, the Plains, and the Southwest, to name a few. The Southeast represents a zone bounded by present-day Texas, Missouri, Georgia, and Florida. This swath is expansive, and covers multiple environmental geographies: from the tropical tip of the Florida Keys to the Ozark Highlands. A quick survey of Native American building typologies from this region is equally expansive, and includes the famous earthen mounds of Cahokia in Illinois as well as the post-and-lintel chickee huts of the Seminoles in Florida. Honing this scope even further, however, we can examine a series of tribes with a major geographic commonality: the Gulf Coast. Many tribes settled along this slow arch of coastline, inhabiting land that today stretches from Florida to Texas; a selection of these groups, moving east to west, included the Calusa, the Apalachee, the Chitimacha, and the Karankawa. READ MORE

News Home Blocks

SAH Archipedia Highlights: Native American Heritage Month

Oct 31, 2023

by

SAH News

In celebration of Native American Heritage Month and the formation of the SAH Indigenous Architecture Affiliate Group, below is a selection of SAH Archipedia content highlighting the contributions of Native American architects. Additionally, a thematic essay on Gulf Coast Tribes explores the building activities of the Calusa, the Apalachee, the Chitimacha, and the Karankawa along a shared body of water. This essay was written by the 2017 Charles E. Peterson Fellow, Willa Granger. Applications for the 2024 Peterson Fellowship are currently open to graduate students until December 31, 2023.

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution

Photograph by Carol Highsmith

The siting of the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall is significant, particularly the building's confrontational engagement with the Capitol building, a form of acknowledgment and contempt for federally supported genocides of Native peoples throughout the nation's history. Prior to the design of the structure, the Museum engaged in a three-year dialogue with Native communities in the United States, Canada, and Mexico to develop a guiding document, "The Way of the People," which shaped the design of the building. One of the most important goals was to highlight that Native communities were not restricted to their anthropological pasts, but instead were alive and active. The museum hired a collaborative group of Native American architects—Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot), Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee/Choctaw), Donna House (Dine/Oneida), and Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi)—to design a building that contrasted neighboring cultural institutions. Most obviously, the building does not follow the modernist and classical forms of the other Smithsonian museums. Even in orientation, the National Museum of the American Indian incorporates Native customs by facing east toward the rising sun. Architecturally, the building’s distinctive curvilinear form evokes a wind-sculpted rock formation not unlike those of the Medicine Rocks in Montana. The five-story structure is clad in golden-toned Kasota stone, a dolomitic limestone from Minnesota. READ MORE

Bosque Redondo Memorial

Courtesy of the Friends of the Bosque Redondo Memorial

The Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner State Monument commemorates the site where thousands of Mescalero Apache and Navajo people were imprisoned between 1862 and 1868. The journey to Bosque Redondo, now known as “The Long Walk,” and the subsequent hardships internment imposed were devastating. Of the 11,000 Navajo (Diné) who departed for Bosque Redondo beginning in 1864, only 6,800 returned in 1868. Bosque Redondo translates from the Spanish as “circular grove of trees.” This inspired architects David Sloan (Diné) and Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee-Choctaw) to design the memorial as a ring of cottonwoods with a visitor center wedged into its northwest side. The arrangement of the trees includes two openings with sightlines toward the Mescalero and Diné homelands. The restoration of the Pecos River watershed along the western edge of the circle offers an exemplary site for teaching the importance of conserving the land. READ MORE

Four Winds High School

Photograph by Steve C. Martens

Working closely with the tribal council, Native American architects from three tribal nations collaborated on the design of this school in Fort Totten, North Dakota. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) design review committee, comprised mainly of Euro-Americans, was reluctant to accept a circular building because of concerns for the cost of such an unorthodox geometric configuration. The local tribal council and Native American architects for the building regarded the unifying tradition of the circle and practical space planning as compatible goals. As constructed, the plan is circular, except for a rectangular extension that contains the gymnasium. Corridors lead from entrances at the four cardinal points to the central space where there is a symbolic eagle enclosure that controls light and sound. In the interest of energy conservation, the school’s exterior has no windows, but desirable daylight is admitted through skylights, and the walls are bermed into the site. Surrounded by Enemy designed vertical concrete signposts at each entrance that are ornamented by abstract representations of an animal or natural spirit (buffalo, bird, elk, and thunder) associated with the cardinal directions. An overall design objective was to increase consciousness and pride in cultural traditions among students attending the school. READ MORE

Gulf Coast Tribes

Mound K, Crystal River Archaeological State Park, Florida. Photograph by Steven Martin

Scholars often subdivide the study of Native American culture into vast, multistate regions, including the Northeast, the Plains, and the Southwest, to name a few. The Southeast represents a zone bounded by present-day Texas, Missouri, Georgia, and Florida. This swath is expansive, and covers multiple environmental geographies: from the tropical tip of the Florida Keys to the Ozark Highlands. A quick survey of Native American building typologies from this region is equally expansive, and includes the famous earthen mounds of Cahokia in Illinois as well as the post-and-lintel chickee huts of the Seminoles in Florida. Honing this scope even further, however, we can examine a series of tribes with a major geographic commonality: the Gulf Coast. Many tribes settled along this slow arch of coastline, inhabiting land that today stretches from Florida to Texas; a selection of these groups, moving east to west, included the Calusa, the Apalachee, the Chitimacha, and the Karankawa. READ MORE