-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Tracing Italian imperial ‘duress’ beginning in the city of deep dish pizza

Apr 16, 2025

by

Amalie Elfallah, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Amalie Elfallah is an architectural-urban designer from the Maryland–Washington D.C. area, which she acknowledges as the ancestral and unceded lands of the Piscataway-Conoy peoples. As an independent scholar, her research examines the socio-spatial imaginaries, constructions, and realities of Italian colonial Libya (1911–1943). She explores how narratives of contemporary [post]colonial Italy and Libya are concealed/embodied, forgotten/remembered, and erased/concretized.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Amalie plans to travel along the eastern coast of the United States before departing for Italy, China, Albania, Libya, and the Dodecanese Islands in Greece. Her itinerary focuses on tracing the built environment—buildings, monuments, public spaces, and street names—linked to a selection of Italy’s former colonies, protectorates, and concessions from the early 20th century. All photographers are her own except otherwise noted.

_____________________________________________________

Chicago, Illinois, USA

During my first trip to Chicago, I stumbled upon many architectural and artistic works I had studied early in my education—including various buildings by Mies van der Rohe, Studio Gang’s Aqua Tower, and Alexander Calder’s Flamingo. Among them, Bertrand Goldberg’s Marina City (c. 1967) stood out with its striking presence along the Chicago River—a building I had not known before, but an urban intervention that left an impression. Yet, my time in Chicago went beyond a fleeting appreciation of modernist and contemporary architectural achievements. I found myself drawn to deeper questions surrounding Modernist discourse—particularly how its forms and ideologies intersect across geographies and historical moments. Central to this observation in Chicago was the role of Italian Modernism during the fascist imperial era (era imperiale fascista) of the early twentieth century.

Fig. 1 – Looking north from the contested Balbo Drive, inaugurated during the Chicago World’s Fair, 1933 (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

I came to this city to see what remains of the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, held under the theme “A Century of Progress,” with particular interest in the Italian Pavilion—its former building footprint now located in Burnham Park. To get there from downtown, I walked down Balbo Drive toward the lakefront [Fig. 1], a street named in honor of a man who wore many hats, but is most notably remembered as the fascist aviator and fanatical PR wingman to Benito Mussolini: Italo Balbo.

As I walked along the edge of Lake Michigan, I was reminded of strolling along a lungomare—those monumental seafront promenades that define many Italian seaside cities and towns. Whether strolling past the various copies of Cristoforo Colombo in Liguria or walking along the streets beside Bari’s fortified walls—reminiscent of Tripoli’s Medina Kadima—a striking sense of familiarity emerged. Yet as I was walking along the lakefront, I was fully aware of what awaited me at my destination: a tangible remnant of history, deeply entangled in the contested discourse surrounding diplomatic gifts from Italy’s colonial—or perhaps more accurately, imperial—era. I do not use these terms lightly, but rather in deliberate reference to the rhetoric of the fascist regime (regime fascista) just one century ago—language that has come to seem disturbingly relevant today.

I had nearly passed what I was looking for, the Balbo Monument, as it sat behind a patch of trees from the pedestrian path. As noted by the Chicago Park District website, the Balbo Monument was a “gift” of Mussolini notably “dedicated on Italian Day in 1934” to not only declare empathy towards his Italian community in the US but most importantly to inaugurate Balbo’s transcontinental flight a year prior at the pavilion’s opening in 1933. Supposedly the column comes from the Roman port of Ostia as scribed in the base of the monument, one panel in English, another panel in Italian. On site, there is no plaque or signage about the monument nor its association to the former grounds of the Italian pavilion.

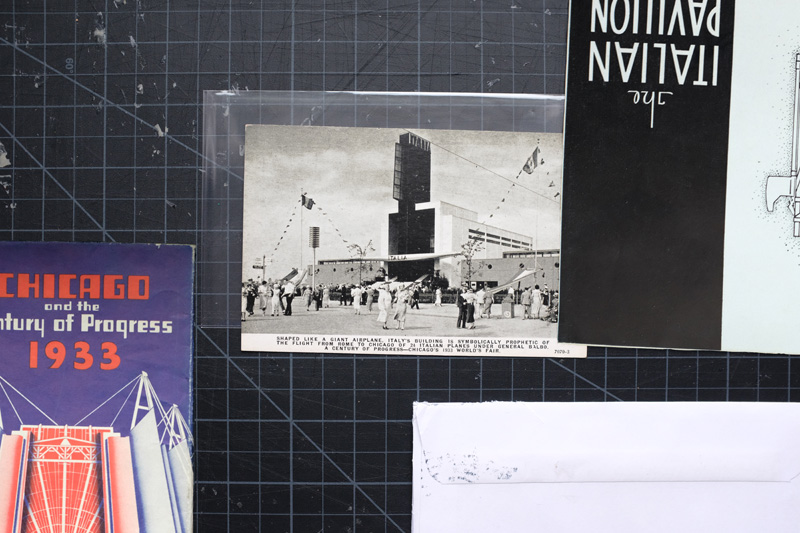

Fig. 2 – Primary material for the Italian Pavillion and the Chicago World’s Fair, “A Century of Progress”, 1933 (Source: personal archive of Amalie Elfallah)

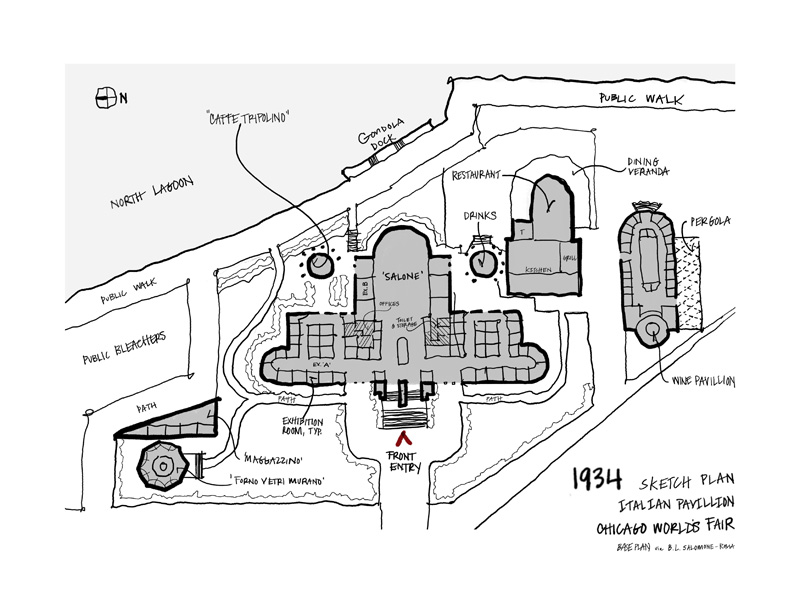

Fig. 3 – 1934 sketch floor plan of Italian Pavillion, Chicago World’s Fair (Source: sketch by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

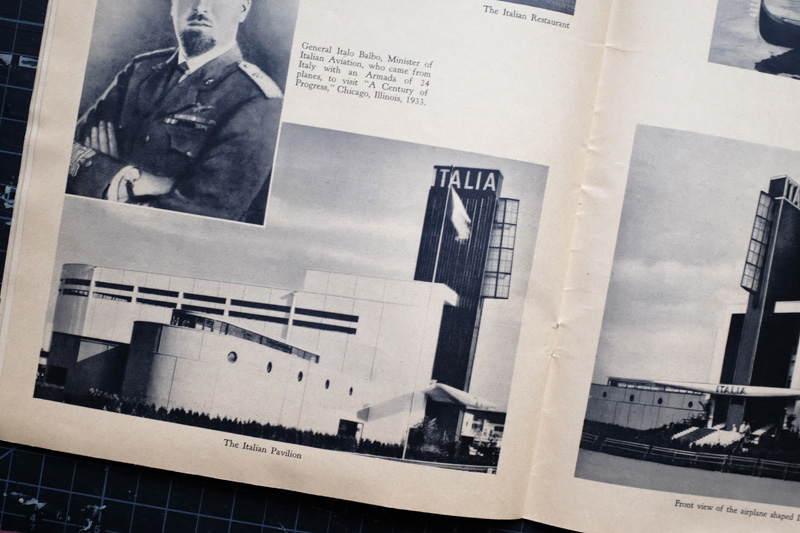

The World’s Fair gathered under the theme “A Century of Progress” in 1933 which encompassed not only international pavilions but also exhibitions from various U.S. states. Thanks to the archivists at the Special Collections and Preservation Division at the Chicago Public Library, I was able to explore a range of primary documentation—pamphlets, postcards, and photographs—that offered initial insights into the fair [Fig. 2]. Some exhibitions within the Italian pavilion were designed to highlight Italy's advancements in aviation, a theme reflected clearly in the building’s architecture. According to the Official Book of the Flight of Gen. Italo Balbo and His Italian Air Armada to A Century of Progress housed in the digitized library of the University of Illinois Chicago, the pavilion itself was constructed in the shape of a “giant airplane” to commemorate the transatlantic flight of Balbo and his armada. The Italian pavilion was designed by Mario de Renzi and Adalberto Libera, who also designed the Mostra della rivoluzione fascista (Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution), which incorporated the fascio littorio—the fascist symbol depicting a body of reeds and an axe. On the Italian Pavillion in Chicago, the fascist symbol became a dominating element on the western façade at the building’s main entry. The rear of the pavilion, as lived, often was garnished with gondolas on the lagoon adding to the essence of Italianità to the site.

In the pavilion’s introductory booklet The Italian Pavillion (1933), visitors were told that Italy had long been “the Mecca of the student, the teacher, and the world tourist.” The text promised an experience that spanned “vestiges of ancient Rome, the splendor of Renaissance Italy, and the history-making progress of modern Italy, through the period of unification, the World War, and under the masterful leadership of Premier Mussolini.” This theme of progress extended beyond the pavilion. Some visitors received a commemorative pin featuring the message 'Welcome General Italo Balbo,' along with an image of Balbo, a plane, and intertwined American and Italian flags, as sold as memorabilia today.

Other fair booklets used Italy’s colonial territories as a stage for promoting the advancements of Italia d’oltremare to showcase its overseas empire often coined as “impero moderno” (modern empire). Brochures depicted colonial holdings like Libya and Rodi as modern extensions of Italian civilization, complete with hotels and infrastructure. This framing might explain the planned “Caffé Tripolino” at the northeast end of the 1934 edition of the pavilion. Although I was unable to find information or images of the café itself, the round space is drawn on the floor plan within the only Italian-language booklet I encountered at the Chicago Public Library [Fig. 3]. Caffé Tripolino appears to have been a deliberate inclusion in the landscape of the pavilion—a café mirrored from a beverage stand (Bibite) on the lagoon side of the building. The pavilion floor plan reinforces Italy’s cultural and political ambitions. There is a strong possibility that, if built, the café spatially evoked Tripoli as a site of Italian influence and leisure—a colonial possession orientalized, as was typical in Italian expositions such as Naples’ Mostra d’Oltremare (1940). As referenced in Brian L. McLaren’s Modern Architecture, Empire, and Race in Fascist Italy (2021), particularly the chapter “An Architecture of Racial Prestige,” an exoticized caffè experience was also inserted into the program of the Padiglione della Libia. Italy’s colonial presence within the Chicago Italian pavilion underscores how colonial spaces were aestheticized and integrated into a narrative of national modernity and imperial identity—even abroad.

Fig. 4 - Surveillance between the brush of path and parking, Italo monument, Chicago (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 5 - Looking through the fence surrounding the Italo Balbo monument, Chicago (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

The location of the Balbo Monument is not too difficult as it sits between the brush of the pedestrian path and a fenced cycling path along the former fair lagoon that is cramp with private boats. One may stumble upon the monument easily by walking from the series of paths from the Field Museum or Adler Planetarium, walking through the ‘Gold Star Families Memorial and Park’ that offers a view of Soldier Field in its full glory. As a local Chicago historic preservation urban planner Susie Trexler noted on how she found the building, “And when I say stumbled upon, I mean it was on the horizon for quite some time and I was drawn in like a moth to light.” The neo-classical foothold to the renovated stadium remains since the World’s Fair. From afar, it feels reminiscent of the Monumento Nazionale a Vittorio Emanuele II—also known as "Vittoriano" or "Altare della Patria”—in front of Piazza Venezia in Rome. The stadium, ironically, was planned in tangent with the Italian pavilion where the column sits today.

Though nothing remains of the pavilion except for the Balbo Monument, the column still rises as high as the surrounding trees that now partially conceal it [Fig. 6]. The monument is well documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey of the Balbo Monument. On the face of the column’s pedestal, a weathered panel bears an English inscription—barely legible—that reads: “This column / twenty centuries old / erected on the beach of Ostia / port of Imperial Rome / to safeguard the fortunes and victories / of the Roman triremes / Fascist Italy, by command of Benito Mussolini, / presents to Chicago exaltation, symbol, memorial / of the Atlantic Squadron led by Balbo / that with Roman daring flew across the ocean / in the 11th year / of the Fascist era.” The Italian version of this inscription remains in better condition—though unfortunately not accessible or useful to most visitors in the city of Chicago [Fig. 7]. The axes of the fasces, once visible at each corner of the rectangular pedestal, have been removed.

Fig. 6 – Behind the fence looking up at the ‘Ostian’ column, Balbo Monument, Chicago (Source: personal archive of Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 7 – Condition of corner fasces and inscriptions, Balbo Monument, Chicago (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

In a more recent article, “What future for Forgotten Monuments?” (2022), professor and archeologist Morag M. Kersel and her students including the co-author, Jack Tessman, explore the challenges to this ideologically fraught monument. They discuss the dissonance of maintaining this Fascist-era relic around a site dedicated to American military sacrifice framing it within broader debates over historical memory and public space. The amnesia that arises from this manmade heritage is reflected in the polarities that can be expressed in Chicago’s WTTW interview “History or Hate? Chicago’s Controversial Monuments and Street Names”, which reveals the polar opinions on how to 'deal' with street names and monuments. In hearing what surrounds this place, I ask myself: What should accompany the monument to contextualize the history of this heritage? What signage and/or intervention can counter the static legacy of Balbo with/without total erasure? In one of many group tours continuing to question the legacy of the site, a working group recounted (Re)visiting the Past in the Present: The Power of Place and the Malleability of Monuments (2024). There is without a doubt, continuing forms of intellectual resistance to the way the Balbo Monument stands today, stripped from context.

Fig. 8 – Portrait of Italo Balbo and the Italian Pavillion in official fair booklet of the Chicago World’s Fair, 1933 (Source: personal archive of Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 9 – [Third]-hand archival collection of Italo Balbo seen in various ceremonies during the late 1930s Italian colonization of Libya (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2024)

Perhaps unknowingly—and largely uncontested—Balbo’s name has been excused from his role in Italy’s colonial history. Italy’s colonial projects, justified under the term sviluppo (development) within Modernist discourses, masked brutal crimes against humanity and the built environment—for which I can personally attest in the case of Libya. If not for knowing Balbo’s complicity in terms of the knowledge and communication with military officials in the schemes of ethnic cleansing and mass migration-settlement plans for Libya—officially documented as ricostruzioni etniche followed by colonizzazione demografica—his monument might not seem so “difficult” to contest.

When I left Chicago, I did not so much think about the monument itself as it stands today but the events that gave it its fame, its heritage. I kept thinking about one of the most striking and uncanny events from the World’s Fair: Balbo’s induction as “Chief Flying Eagle” into the Sioux Tribe at the site of the “American Indian Villages”—one of several curated “villages” on the fairgrounds. Given Balbo’s complicity in the ethnic cleansing of peoples in eastern Libya (Cyrenaica), the irony of the ceremony is difficult to overlook. Had Native American leaders been aware of Balbo’s role in his impending colonial venture, what might the outcome—or resistance—of the ceremony have been? This moment underscores a troubling historical amnesia between diplomatic spectacle and colonial violence—an amnesia that must be confronted when reflecting on the legacy of the Balbo monument.

Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Fig. 10 – Missing replica of a Capitoline Wolf, North Ogden and West Grand, Chicago (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

A fresh coat of metallic paint inscribes, “Il Governatore Di Roma Alla Citta Di Cincinnati” (The Governor of Rome to the City of Cincinatti) below the replica of the Capitoline Wolf in Cincinnati’s Eden Park. What is not re-gilded in a metallic is “1931 – Anno X” [Fig.13] denoting the fascist year the monument was gifted by Mussolini to honor Cincinnati’s namesake, the Roman hero Cincinnatus. This wolf, Remus and Romulus, sit in a neighborhood park overlooking the Ohio River [Fig.11/12].

Unlike Chicago’s Balbo Monument, Cincinnati’s wolf is accompanied by two descriptions: a grounded plaque and a raised signage about the history of the monument. The plaque is casted in that grainy aggregate concrete typical of many public parks. It recounts the origins of the monument as a “a gift from the City of Rome, Italy […] dedicated in 1931” followed by describing the “folklore” around the story of Remus and Romulus. What is null from this description is that it was gifted by the Italian fascist regime in a series of years which diplomatic “gifts” were sent in various places across the globe. However, the ADA accessible signage— appearing to be recently installed—provides further details about the history of the monument. The signage notes the original replica of the Capitoline Wolf was commemorated September 20, 1931 by local Italian community chapter Order Sons of Italy in America (OSIA) Rome. This gesture was more than diplomatic—it was supposedly a bold declaration for Italian immigrants.

Fig. 11 - Eden community park where the Capitoline Wolf stands overlooking the Ohio River, Cincinnati, Ohio (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 12 - Viewing the recently "rededicated" Capitoline Wolf along the path of Eden Park, Cincinnati, Ohio (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 13 - Statue description below Capitoline Wolf, Cincinnati, Ohio (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 14 - Viewing up close the "2023 Rededicated" Capitoline Wolf, Cincinnati, Ohio (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

As noted in the updated signage, the statue’s physical journey has been fraught with contestation. In 2022, the wolf was taken, leaving only the paws and twins at the base. The official rededication in 2023 transformed the statue, for some, a testament to cultural perseverance. The wolf’s meaning has both evolved and dissolved. Its latest iteration may no longer carry the weight of its fascist-era origins. As one patron told me passing by the monument, their dog was startled when the new wolf had been installed [Fig.14]. Although my visit was brief at Eden Park, I was reminded that public artifacts are never static—they are contested, erased, and remade, much like the identities they commemorate and the ones they silence.

It’s telling that when one Capitoline Wolf went 'missing in action' in Cincinnati, another surfaced in Italy’s formerly occupied territory: Benghazi. There on the Mediterranean coast, it was not a diplomatic gift—the rediscovered Capitoline Wolf in Libya stood instead as the long forgotten symbolic expression of colonial rhetoric and territorial dominance. In August 2023, “Libya recover[ed] colonial wolf statue sold as scrap and found on a farm,” discovered near Benghazi. The 80-year old owner bought it admitted it looked similar to a statue on the port when he was young. Under Italian occupation, both a Capitoline Wolf and a Venetian Lion stood on columns along the lungomare in Benghazi, just like Tripoli. It’s a strange, haunting coincidence—how the Capitoline Wolf continues to reappear across geographies like a ghost, reminding us that the past never fully disappears waiting to be seen again.

Washington D.C. USA

Before traveling overseas for this fellowship, I set out to trace local remnants that reminded me of the 'duress' of Italy’s imperial past. As Ann Laura Stoler writes in Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times, duress is 'a trace but more often an enduring fissure, a durable mark,' and it is 'tethered to time but rarely in any predictable way.' After studying and living in Milan during my master’s program—where I began to recognize the 'duress' of an erased colonial history—I wanted to use this fellowship as an opportunity to trace a broader constellation of duress: one stemming from, or brushed off from, Roman antiquity and its modern ghost, fascism.

In this momentous time, I am indebted to speak about the prominent fascio on the George Washington monument in the public park on the university grounds of George Washington University. The fascio stands nearly three-quarters the height of George. The monument, like the previously discussed tangible heritage, has been fraught with physical contestation most recently during the student encampments protesting the ongoing genocide of the Gaza strip and ethnic cleansing of Palestine. This might explain the newly fashioned retractable steel gate casted on concrete piers.

Not unlike many DC employees, university faculty, and tourists in the vicinity of the Foggy Bottom neighborhood nearly one year ago in 2024, I witnessed the student encampments. I had visited on a Friday during Salat Al-Jumma’, meaning Friday Prayer, comparable to Sunday Church day: a sermon followed by prayer [Fig. 16]. I remember students inhabiting the public space with their tents surrounding the monument, community members managing the first aid tent, students passing to classes and eating lunch at the round tables nestled in the building courts while people gathered on rugs and mats aligned to Mecca. The atmosphere was peaceful and the fleeting temporal moment of this urban space lasted just days before its forceful dismantlement.

Fig. 15 – Newly barricaded University Yard Park in front of George Washington Monument, University Yard, Washington D.C. (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 16 – Student Encampment extending past the George Washington Monument, University Yard, Washington D.C. (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2024)

Fig. 17 – Detail of base fasce, George Washington Monument, University Yard, Washington D.C. (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Now, the George Washington monument sits in pristine condition, as if it were never touched [Fig. 17]. Though many details from a year ago linger in my memory, one moment is seeing a paper-folded kite sway in the wind at the base of the monument tethered by a string to a piece of duct tape. The kite read, “If I must die, let it bring hope. Let it be a tale. – Dr. Refaat Alareer.” The kite, which would soon disappear like the tents, leave no trace in sight. The copy of Edward Said’s Orientalism in the tent labeled “Art Supplies,” gone. Signs written in Sharpie acknowledging, “There are no more universities left in Gaza” taken down. But the legacy, like the Palestinian poet Refaat Alreer—his life taken away during the genocide—have left their tales across encampments and those who continue to discuss the ongoing genocide—'urbacide’ and ‘scholasticide’ in the Gaza Strip—taken place, as recently acknowledged and condemned by the Organization of American Historians (OAH).

Like on the George Washington Monument, fasce appear all across Washington D.C. The National Park Service even describes the fasce as a ‘Secret Symbol of the Lincoln Memorial’ when clearly it is an appropriated element from ancient Rome. One may also find this symbol around the National Mall, for example, in front of the National Archives [Fig. 18]. It seems pertinent before departing to Italy to share examples of this ‘imperial duress’ that thrived off desires to recreate a ‘modern’ Rome re-imaging this ideology.

Fig.18 – Fascio symbol held by statue in front of the National Archives undergoing preservation, Washington D.C. (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig.19 – Bronze copy of Capitoline wolf, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 20 – Copy of Capitoline Wolf in the Georgetown neighborhood, Washington D.C. (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

After walking past the National Archives, I walked into the strip of Smithsonian Museums to see another replica of the Capitoline Wolf at D.C’s National Gallery of Art [Fig. 19]. It stood in the center of the room, spotlit among an eclectic mix of objects on pedestals. Later, I encountered yet another replica—this time in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. [Fig. 20]. Like the layers of fascist symbolism, from its ancient origins to its modern reinvention under Mussolini, these figures often sit stripped of context, their ideological weight rendered nearly invisible. As I continue my journey to Italy, I hope to trace these ghosts embedded in the built environment and confront the lingering tensions they carry.

Around Milan, Italy

By regional train from Milan, I made my way to the quiet suburb of Riozzo located in the Commune of Cerro di Lambro near the city of Melegniano. There, I had planned on visiting a monumental arch that reminded me of the Italian architect Florestano di Fausto’s l’Arco dei Fileni which “famously” marked the “roman crossroads” between eastern and western Libya known as “Tripolitania and Cyrenaica.” In the section ‘from Tripoli to Benghazi’ of a common Touring Club Italia guide from the 1930s, the arch was described as: “31 meters high and in modern colonial style, st[ood] 680 km from Tripoli, far from any inhabited center, where the coastal road ha[d] cost the greatest sacrifices and where it [could] also serve to remember the ancient Arae Philaenorum.” The arch was more than a imperial gesture but a monumental backdrop for publicity by the fascist regime notably upon Mussolini’s spectacularized visit to Libya in 1937. What stands in Riozzo, is it a mock-up, standardized form, or even replica of Libya's Arco del Feleni?

Fig. 21 - Road signage of Via della Vecchia Chimica near the towering arch, ex-military chemical plant, Riozzo, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 22 – ‘Humana’ donation bins in front of the recycle area in front of the towering arch, ex-military chemical plant, Riozzo, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

While the Arco dei Fileni no longer exists, the arch in Riozzo stands nearly 30-40 meters high. The location of this arch in a former industrial chemical site [Fig. 23] sits in ominous grounds. The site is catalogued as cultural heritage by Italy’s Ministry of Culture: Ex Stabilimento Chimico Militare (Former Military Chemical Plant) although notably cited from “1941-48.” According to a local news outlet, the enclosed area are the remnants of the former Saronio Chemical Industry founded in 1926. The 1998 local newspaper clipping from Città di Melegnano discusses the history of the chemical industry. A more recent article, the area is referred to as a “former military plant […] famous for the production of chemical weapons during Mussolini’s regime” but is set for a major transformation in these years to come. You can see the remaining structures in a 2011 interview by Italia Nostra -- a National Association for the Protection of the Historical, Artistic, and Natural Heritage of the Nation -- entitled “Fantasma di cemento, Milano Sud” (Concrete Ghost, South Milan). As the reporter Isabella Schiavone, noted, “you can find all kinds of material, rubble, decay, crumbling buildings with black walls from the fumes produced by the factory before it became a military training area and was then abandoned."

It was evident when I walked around the site there is a ghostly presence being countered by new construction near the local dog park which shares the wall of the site’s enclosure.

Sentiments expressed to me by a local patron are also reflected in articles and interviews: The concern for the degradation of the site has been prominent for many years. The gentlemen I spoke with worked in the area directly in front of the arch surrounded by a parking lot. As patrons came to dispose of things— like household items, metal scraps, ectara— I introduced myself asking questions about the arch above us. When I asked him about it, he immediately referenced Mussolini and thought that “it was a structure that was used to contain water.” He continued saying that they did “military chemical things” and there was a “factory where they made bombs and chemical weapons.” It is evident that the transparency about the site is known by the community, yet, life has developed around it notwithstanding the possible health concerns.

Fig. 23 – Building conditions looking thought the gates, ex-military chemical plant, Riozzo, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 24 – Cats inhabiting the ex-military chemical plant, Riozzo, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 25 – Cat signage on the gate around the ex-military chemical plant, Riozzo, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

On the opposite side of the enclosed site, one will find a gate with a straight axis to the arch lined with abandoned and degraded buildings [Fig.23] belonging to the former industrial site. There are cats that pass freely in and out through the boundary that also inhabit the degraded structures [Fig.24]. Next to adhoc installation of a series of stacked small-scale homes that house a community of cats, a sign posted on the gate notes, “Cats are protected by the state […]. It is forbidden to take them away from the places where they usually find refuge, food and protection. […] Citizens are allowed to feed and care for cats in compliance with their good health and hygiene rules” [Fig.25]. As I walked the underpass that splits Melegnano from Riozzo, a split made by the regional train track, my thoughts brought me back to the words of additional notes by Stoler on duress: “The acrid smell of industrial rubble masks, and is often more palpable than, the toxins of imperial debris.” The arch, and the ghosts that mask the past, are merely a sign for the amnesia that remains about its associated history.

When I returned to Milan, even when I planned to attend to do tourist activities beyond an itinerary, there was a constant unintended encounter with the colonial past. This happened when I attended the ongoing exhibition of the Italian artist Arnaldo Pomodoro, known for his bronze sculptures across the globe. I was in awe of the immense, mysterious, and intricate sculptures [Fig. 26] in Open Studio #3, but only momentarily.

My mind was taken back to a couple years ago in Rome when I passed by one of Pomodoro’s sculptures outside the diplomatic archives. When I approached the exhibition’s metal filing cabinets that archived Pomodoro’s install locations, I pulled the drawer ‘Roma’ knowing I would see the ‘la sfera sul piazzale’ [Fig. 27]. I was reminded not only by the sculpture outside the Palazzo della Farnesina, but my memories attending the archives in the building which this sculpture embellishes. The only photo I had taken that captured the sculpture focused on the pedestrian crosswalk that capped a landscape barrier [Fig. 28]. As expected when I opened the drawer at the exhibition, a rush of memories, rather scars of witnessing the images and documentation of Italy’s occupation in Libya, within the Palazzo della Farnesina, returned. And rather letting those images flood the mind of endless connections to the constellation of this dissolved history, it reminded me that, again, there is a constellation of connections of the past with the present.

Fig. 26 - Fig. White model of studio work by Arnaldo Pomodoro, ‘Open Studio #3’ Exhibition, Milan, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 27 - Documentation of Arnaldo Pomodoro’s sculpture outside Rome’s Palazzo della Farnesina, ‘Open Studio #3’ Exhibition, Milan, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 28 – Crosswalk to the Diplomatic Archives, plaza with sphere by Arnaldo Pomodoro, Rome, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2022)

Pomodoro’s sculpture in Rome stands in front of the former Littorio Palace—the headquarters of the former National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) and its related bodies—now housing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. Nearby, a towering obelisk, nearby, is scripted vertically with “MVSSOLINI” above “DVX” and a fascio littorio. The monumental complex, especially the former PNF headquarters is a reminder of Italy’s imperial past. In my case, it was a reminder of the concealed narrative of what happened in Libya not well known nor acknowledged in Italy today. At the diplomatic archive, I was able to witness printed photographs of the concentration camps (campi concentramento) in Cyrenaica during what some scholars like Eric Salerno, Ali Abdulatif Ahmida, and Giorgio Rochat have referred to as a genocide in Cyrenaica. The amnesia surrounding what happened in these enclosed desert camps is largely perpetuated by the static descriptions that remain attached to them—such as the label accampamento romano (Roman encampment) found in Milan’s civic archive—which horrifically reduces both the conditions of these places and the experiences of those who survived them. Narratives from the concentration camps remain as oral histories yet to be coalesced. Some accessible narratives have been documented through poetry and interviews from 1929-24 collected by professor Ali Abdullatif Ahmida in Shar: A Hidden Colonial History of Libya (2021). In every tangible reminder, encounter with colonial history, it become increasingly clear that histories too make narratives invisible. In a conscious step along this fellowship, I aim to deconstruct what Marie-Louise Richards refers to as ‘hyper-visible invisibility’ to continue tracing the poetics of the unseen.

As I continued walking from Pomodoro’s studio along the Navigli di Milano, a well-known area along the canal system of the city of Milan, there was a flea market of countless goods including second-hand trinkets and clothes [Fig.29]. I came across a tent selling old stamps and thought I may find a ‘modern relic’. Indeed, under ‘colonie,’ I found both unused and used postage stamps extracted from letters and postcards from Libya and Rodi during the Italian colonial period [Fig. 30]. I had seen the images of such stamps before, but having Di Fausto’s Arco dei Fileni reappear just after a visit to Riozzo’s arch brought yet another unintended encounter with Italy’s colonial history.

Fig. 29 – Flea markets, Navigli di Milano, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)

Fig. 30 - Unused and used postage stamps extracted from letters and postcards from the Italian colonial period, flea market along Navigli di Milano, Italy (Source: photograph by Amalie Elfallah, 2025)