-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Çatalhöyük: The Dawn of the Architectural Dream

Apr 1, 2025

by

Francesca Sisci, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Francesca Sisci is an architect and adjunct professor at Polytechnic of Bari, Italy. She has a PhD in Architectural Representation and her approach of research is distinctive in its integration of multiple disciplines, including art history, architectural theory, and photography. She focuses on exploring aspects of visual perception and how these can be translated into images.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Sisci is exploring the feminine imaginary as it applies to architecture from ancient to contemporary structures. She will explore this important question by trying to identify the types of architectural spaces that in different ways are connected with the female gender. In the course of a 6-month itinerary she will visit sites in Sardinia, Malta and Gozo, Türkiye, Crete, UK and Ireland, Norway, Greenland, the northeastern United States, and Mexico. All photographs are by the author.

_______________________________________________

I chose to study architecture not out of mere curiosity about the profession, but because of a deeply personal need. Looking back, I now see that need as a search for origins—a fundamental essence that connects all human beings. It is the same essence that, over time, has shaped the way we conceive and choose the spaces we inhabit, turning them into reflections of our beliefs and values. In the end, the places we live in are not just where we reside—they become a part of us, just as we become a part of them.

To do this, to rediscover the original connection between people and the spaces they live in, I decided to travel back in time, trying to reach a lost era when the word 'image' could only correspond to reality or dream. A time when everything had a physical presence, and the form of each carefully crafted object was a clear reflection of a need, with little outside influence or reference.

The journey to this privileged time, in which the need for imagination preceded the image, begins at the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük (7400-5200 BC).

The archaeological site is located in the present-day province of Konya, specifically in the Çumra district, at the southern edge of the Turkish Anatolian Plateau. Its discovery dates back to the mid-20th century, and the first excavation campaigns were led by the archaeologist James Mellaart between 1961 and 1965, followed by those directed by Professor Ian Hodder from 1993 until 2017.

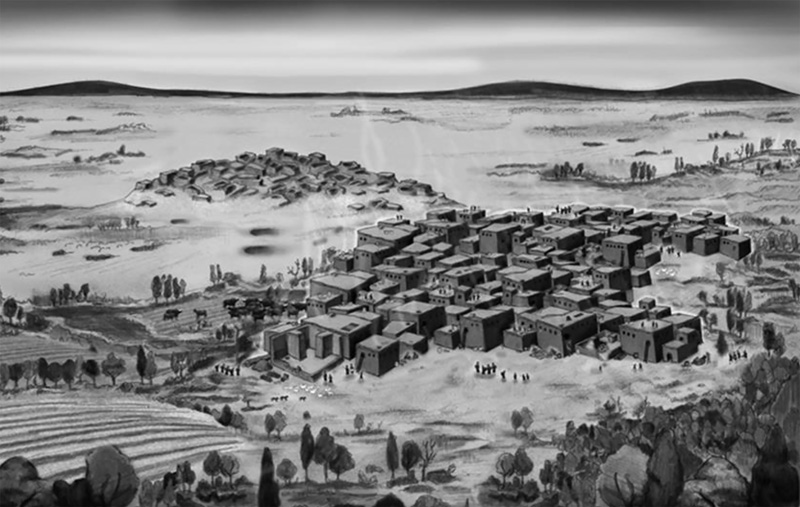

The archaeological area consists of two large mounds that rise above the flat plateaus, about 1000 meters above sea level. Known as the West Mound and East Mound, both have been excavated and, since 2012, have been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 East and West Mounds at Çatalhöyük. Çatalhöyük Research Project.

The remarkable fame that the archaeological site of Çatalhöyük has gained, even among those outside the field, is due to the discovery of two artifacts that have sparked different interpretations due to their characteristics. Both are housed at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, which represents a true gateway to the deeper history of the region.

The first artifact, and perhaps the most famous, is the molded clay figurine depicting a seated woman on a throne, flanked by a pair of leopards, found in a seed storage compartment. The second, no less important, is the wall painting, considered from the outset to be one of the earliest urban representations in human history. Much has been written about each of these artifacts, but no definitive and agreed upon interpretation of their use and meaning has been reached. These are things that often happens with everything that reaches us in the form of a fragment from another reality. However, questioning the ambiguity of these two artifacts is nothing more than another layer of uncertainty and doubt that permeates the entire archaeological site of Çatalhöyük.

There are several ways to reach Konya, the main city near Çatalhöyük, but traveling slowly and independently is in itself an essential experience, almost preparatory. Leaving the bustling capital, Ankara, and heading toward the interior of Anatolia means a gradual departure from the signs of a Turkey dedicated to progress: layer upon layer of suburbs, where new lonely skyscrapers already seem outdated, a reminder of a burnt-out desire (fig. 2). Outside the urban areas, the steppe stretches endlessly on the horizon, occasionally interrupted by futuristic service areas or small agricultural villages.

Fig. 2 A view of Ankara's suburbs.

The winter light that accompanies my journey makes the colors vivid and the contours of the landscape sharp, gradually shifting the perception of the surrounding space into an alternative dimension. The city, with its chaos, its visual and temporal disorder, is now behind me. I drive for miles on straight roads without meeting another car, surrounded by a snowy desert, and I say to myself: "Robert Zemeckis is right: a straight road, a DeLorean, and you can travel through time" (figs. 3, 4).

Figs. 3, 4 Views of the Konya Plateau.

Küçükköy is the last village before the final destination: a few dozen old rural houses, piles of firewood at the entrance and many agricultural vehicles worn out by time and work. The modest, perhaps somewhat neglected, but quite authentic aura that you feel as you pass through the village suddenly disappears as you reach the entrance to the Çatalhöyük Visitor Center. Funded by UNESCO, the new wooden structure was designed with landscape protection in mind, and inside it houses a museum that has been built using innovative methods and tools, with a special emphasis on active visitor participation. Büsra is my guide and with her I travel through several millennia of history in just one hour. She tells me how these same plateaus, now cold and arid, were once fertile and mild: flora and fauna thrived, and for millennia the area now known as Çatalhöyük was the setting for the life of a civilization in transition. In fact, the earliest dates go back to 7400 B.C., placing it in that limbo that lasted for several centuries, during which, along with a climate shift toward milder temperatures, the social organization of Homo sapiens adapted from nomadic hunter-gatherers to settled herders and farmers. It is during this period - the early stages of the Neolithic, marked by significant changes and the emergence of new needs - that the first form of architecture appears in the history of our species.

With Büsra, I continue my journey, and after placing the site in a temporal and environmental context, we move on to the mounds and what they have carefully preserved to this day. I am very surprised to realize that the shape of the mound itself is derived from the way this place was conceived and used by this lost civilization at the dawn of time. In fact, the stratification that makes up the mounds of Çatalhöyük is not only the normal condition in which any archaeological site presents itself to scholars due to the passage of time, but also the result of how the same community for millennia stacked one dwelling and sanctuary on top of another, creating the largest and oldest human settlement in history. Thus, the mounds of Çatalhöyük are the sum of at least 18 different layers built over 2200 years by the same civilization (eastern mound 7400 BC to 6200 BC, western mound 6200 BC to 5200 BC). The mounds rise about 20 meters above the Konya plain, and in this small depth lies a time that surpasses the history we know, surpasses the years we mark on our calendars. Trying to imagine this space-time gives me a sense of dizziness and wonder. I had chosen to come here, the heart of Anatolia, with little information, following the instinct of an intuition and entrusting the journey with the task of educating myself. I did not expect that something much greater would happen: a true and profound emotion.

In the many layers that make up the mounds, there are houses on top of houses, shrines on top of shrines, burials on top of burials... lives on top of lives.

I thank Büsra, and before ending the visit with the rooms dedicated to the reconstructions of the dwellings, I decide to go directly to the excavation to observe it with fresh eyes, to imagine it without images, but by trying to remember. After all, the civilization to which I belong is an evolution whose total time is shorter than that of the last inhabitant of Çatalhöyük. Something must have remained, something in my gestures, in my needs, even if unconsciously, it must still be a part of me.

Fig. 5 Çatalhöyük, East Mound.

The mounds are not far from the new cultural center, a wooden walkway marks the path next to the small former museum. It is 26°F (-3°C) and the snow has turned the landscape white. There are very few visitors besides me, and on the way to the shell that protects the north excavation area of the eastern mound, I try to imagine what the place must have been like over 9000 years ago: lush with trees, including fig trees, and with leopards hidden among the branches, ready to hunt (fig. 5, 6). As I enter the protective structure of the excavation, the striking view offered by the exposed remains is imposing, yet at the same time imbued with a quiet aura. The intact parts of the walls and floors seem to be silent witnesses (fig. 7). The individual bricks, made of a mixture of mud and straw, reconstruct a landscape that deceives the eye, leading me to ask myself: “was the mound there first, with these spaces excavated within it, or was it the earth that gradually covered them forming a mound? Looking more closely, despite the perfect chromatic continuity between the ground and the structures, I begin to distinguish rooms, living units, leftover spaces, and the points where the hearths and burials were arranged (figs. 8, 9, 10).

Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10 Çatalhöyük, East Mound excavation area.

The excavation reveals only a tiny part of what the actual size of the village must have been. I stay for a long time to observe the excavation, using all the vantage points that the prescribed path allows me. I try to imagine the gestures and reasons that led to these forms - what kind of life unfolded in them?

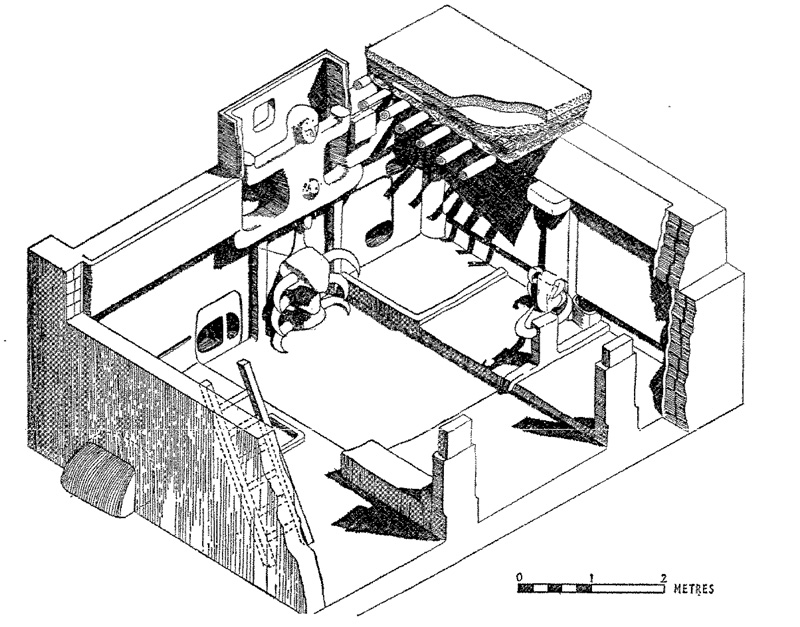

The true purpose of these spaces remains a subject of ongoing debate and unresolved discussion. Many hypotheses have been proposed over time. James Mellart in his Çatal Hüyük: A Neolithic Town in Anatolia (1967), suggests the existence of two distinct uses for the spaces: domestic and sacred, i.e., homes and shrines. More recently, Ian Hodder, in Çatalhöyük: The Leopard's Tale (2006), argues that such a clear division does not exist, believing instead that the spiritual aspect was perfectly integrated into the process of foundation, construction, and demolition of both the entire dwelling unit and its internal arrangement of elements. Hodder supports his theory with various archaeological findings, such as the discovery of burials in the foundation layers of buildings, particularly at thresholds, or the discovery of ritual objects such as animal bones or female figurine fragments embedded in domestic elements, such as clay domes used as ovens . Domestic space and sacred space were one and the same. The home was a place to live and perform rituals, and everything was perfectly integrated into the social dynamic. In this light, the very act of piling houses on top of each other becomes an expression of both ritual and necessity. In some cases, this phenomenon occurred several times for a single dwelling, leading Professor Hodder to propose the theory of History Houses , a term he uses to describe a group of individual, independent dwellings that underwent a ritual process of demolition - tearing down, burning the remains and preserving only certain elements considered important, such as parts of skeletons from previous burials - and rebuilding on the same site, incorporating the saved elements into the new house. Amazingly, in some cases this ritual was repeated up to six times for the same dwelling, at intervals of 70 to 100 years, for a total span of several centuries (fig. 11).

Fig. 11 A diachronic perspective on the South Area at Çatalhöyük. In Bleda S. Düring. “The Articulation of Houses at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey”.

The house, the domestic space, connects us directly to the deepest history of humanity. The cramped spaces of the temple houses at Çatalhöyük enclose a cosmos and are at the same time a tangible expression of it. Like shells that had to be entered through a hole in the ceiling with a ladder above the hearth, they offered shelter from the harsh outside world (fig. 12). In this dichotomy of outside/inside, the walls of raw brick were the thin membrane of separation between danger and safety, and within them everything had to fit: all the parts that make up and participate in the unfolding and development of human life. In the houses of the village, which usually consisted of a single large room next to narrow service rooms, people cooked, ate, slept, stored provisions, maintained social relationships, made decisions, dreamed, conceived, gave birth, died, buried their dead, honored their ancestors, performed rituals... and everything started again, so the house stratified its history, which coincided with that of the people who had created and inhabited it. Houses as families, homes as individuals, with their own personal body and history, body and memory.

Fig. 12 Reconstruction of a dwelling of Çatalhöyük (the window on the left wall does not exist in reality).

Then I begin to think that the impossibility of separating the sacred, and thus the ritual, from the domestic space lies in the fact that the house was the guardian of life, and life must have been perceived as the most sacred thing. So what did architecture mean to those who built the village of Çatalhöyük? Perhaps the deepest reason that drove them to imagine permanent, structured dwellings for the first time was the need for a space capable of protecting life, allowing it to happen and unfold, and at the same time protecting its most delicate and fragile moments.

Building and inhabiting a space born from this deep sense of necessity and sacredness meant creating something that went beyond the mere technical act. In this regard, among the various features noted by archaeologists, one is particularly interesting and symbolic. Except for a few rare cases, in the vast majority of cases the houses, although built very close to each other, maintain their independence. In other words, a principle of economy that would involve sharing a wall to create adjoining units was not applied. This led to the creation of a very unique layout, made up of blocks placed very close to each other but never touching, with narrow remaining spaces that are not always usable as walkways. They seemed to have technical skills, as they were able to reinforce areas subject to ground movement. What remains to be hypothesized is that this individuality was a deliberate choice: a dwelling as a body, a body with its life cycle of birth, growth, death, rebirth, growth, death.

One could say that the inescapable cyclicality of existence and its fragile ability to persist in the world were among the main themes around which this Neolithic civilization shaped its social and ritual model. It is known that from even earlier times, going back to the Paleolithic, a cult known today as the Mother Goddess was widespread. The word cult seems difficult to contextualize in relation to such a distant era, but what the archaeological evidence suggests is the existence of a social and ritual role for women, since, as we have seen, these two levels are difficult to separate.

Many studies have been conducted on the different roles based on gender - male or female - and the conclusion presented by Professor Hodder is that the social organization of the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük was basically egalitarian. Scientific data, such as the analysis of diet, grave goods, or the frequency and manner of gender representation in paintings or figurines, did not reveal a clear superiority of one gender over the other. In a context of balance, age seemed to be the determining factor. Whether male or female, the elderly had an important social role.

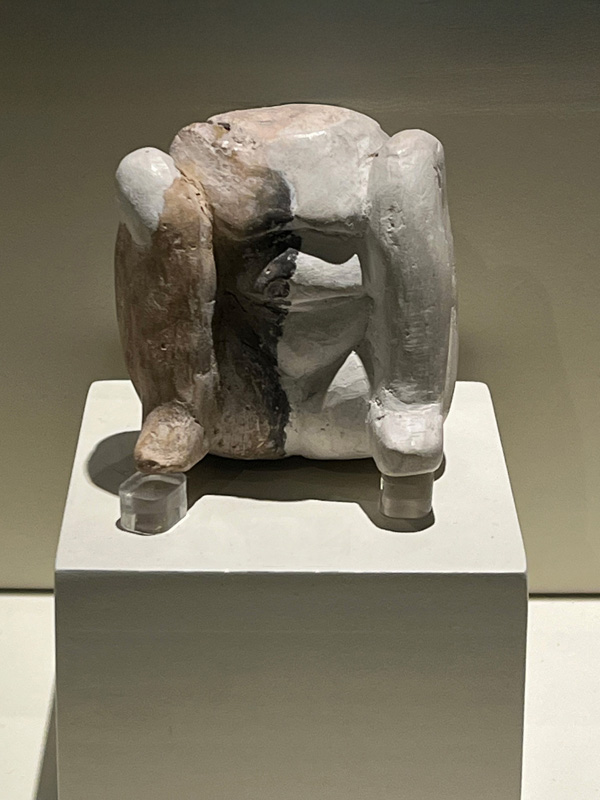

Fig. 13 Goddess Figurine, terracotta, Çatalhöyük 5750 bc. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

To confirm that a woman could take on the role of group leader, one could look at the figure of the Woman sitting on a throne flanked by two leopards (fig. 13). Her posture, her imposing presence, and especially the two animals, symbols of both strength and a strong sense of motherhood, convey authority to all who look at her. In addition, many other female figurines of various sizes and types have been found. Many are on display in the Neolithic section of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara and come from different sites but same geographical area. These small statues are striking for their beauty and elegance, but also because they share recurring physical characteristics: ample breasts and hips, a prominent abdomen (perhaps pregnant) (figs. 14, 15, 16), and in some cases they depict postures closely associated with the act of childbirth (figs. 17, 18).

Figs. 14, 15, 16 Female figurines.

Figs. 17, 18 Female figurines in childbirth pose.

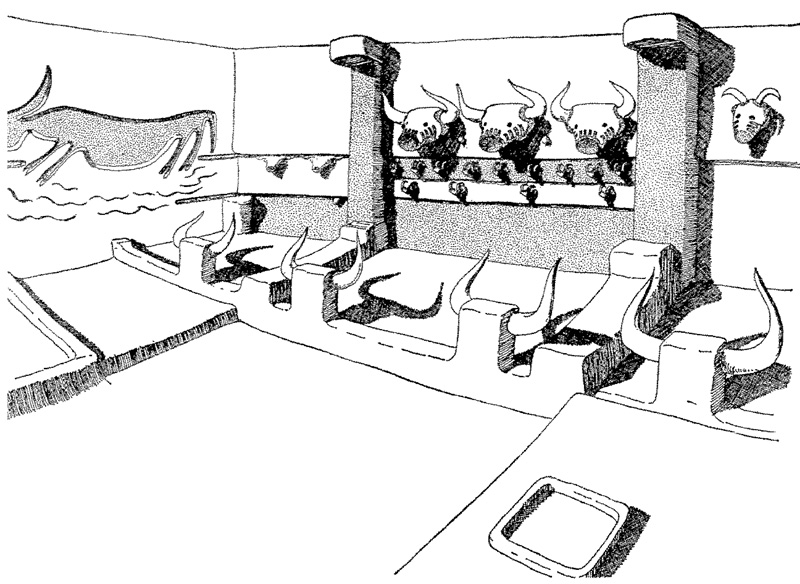

Marija Gimbutas, in her famous book The Language of the Goddess, in the chapter Vulva and Birth, shows that this symbolism is an ancient legacy, with its first interpretations dating back over 30,000 years. She traces the evolution of representation from two-dimensional to three-dimensional. In the Birth Shrines section, she even hypothesizes the existence of actual spaces where rituals related to childbirth and birth itself took place. She specifically mentions the Red Shrine, so named by Mellart in his document Excavations at Çatalhöyük, 1965. Fourth Preliminary Report for the red ochre color that covered the entire floor and walls. This peculiarity, found nowhere else, along with other elements such as chevron patterns and figures depicted with their legs apart - a stylization of the birthing pose - led the archaeologist to hypothesize that this room had a specialized function (fig. 19). As with any subject related to the ancient, in this case almost lost world, interpretations can be more or less correct but they all offer significant opportunities for reflection. Any interpretation makes it clear that no object is isolated, whether it's a figurine of a goddess or an entire structure, and this becomes even more evident when each object or place is assigned a meaning that transcends its materiality and enters the realm of the symbolic and ritual.

Fig. 19 In James Mellart, Excavations at Çatal Höyük, 1965. Fourth preliminary report, plate XLIX.

My journey to Çatalhöyük has taken me to the point of contact between the real and the dreamlike, that point where architecture has emerged as a tangible expression of an inner world, made up of objects as symbols and places to be welcomed like maternal wombs. The form of this architecture, as well as its dimension, are not adaptations to a type or a model, but real evidence of a feeling.

Fig. 20 In James Mellart, Çatal Höyük. A Neolithic Town in Anatolia, p. 127. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York 1967.

Fig. 21 In James Mellart, Çatal Höyük. A Neolithic Town in Anatolia, p. 128. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York 1967.

Fig. 22 View of the Konya Plateau.