-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

One-crop country: Agricultural and Trading Heritage in Gambia

Oct 9, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this third installment of his travel blog, he explores structural remnants of past regimes still serving present-day peanut industry. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo."

Part Two: "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future"

___________________________________________________________________________

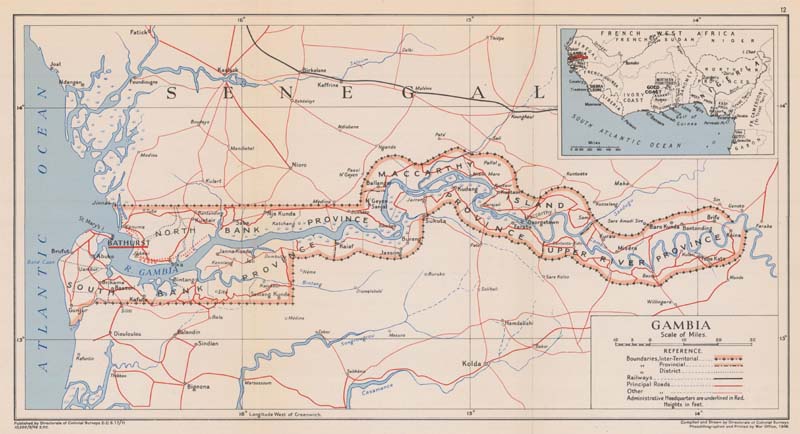

Narrow as it is along the bends of the watercourse that runs its entire length—a whole country made up of the two opposite banks of the river—The Gambia seems to lend itself readily to a simplification that would be unlikely for the other places I’ve visited in the past months. I look at its shape on an old map. It’s one of those artificial boundaries that could only have emerged from a colonial fantasy. Not a straight line through empty land, but a succession of semicircles traced with a compass, taking the bends of the river as the center. This fixed on paper an agreement reached after a long colonial rivalry, culminating in the formalization of British control over the area surrounding the Gambia river, roughly for the length of its navigability, while the French retained control of the surrounding land.

I look at the map, and it reminds me of something I read in a report on commercial activities in the area, written by one of the largest colonial companies operating in West Africa, which I had noted in my journal. The Gambia—the report states, referring to the economic dynamics of the country in the 1950s—is a one-crop country, with virtually no natural resources or industries. For the purpose of the study, such ‘simplicity’ offered an opportunity that other regions like Nigeria, Ghana or Congo, in which the company operated, could not offer: it can be observed “with the precision of a laboratory experiment.” 1

A rather crude way to flatten differences and dismiss the nuances of history, but bluntness, as I came to learn, is a skill that colonial administrators and businessmen alike quickly learned to appreciate. And yet, despite my annoyance with such hasty representations, I admit that that sentence I had noted down is part of the reason why I decided to come to Gambia.

That 'one-crop country' from the country report piqued my curiosity and led me to further research. The 'one crop' was, of course, groundnuts, or peanuts, introduced to the country as an export product in the early 19th century by British traders and since then, one of the material symbols of historical transformation and cultural resilience, embedded in the nation’s story of colonialism, independence, and the daily life of its inhabitants.

Fig. 1: Map of Gambia, Directorate of Colonial Surveys, 1948.

Fig. 2: “FAO - Food for Mankind”. Gambian circulating commemorative coin depicting peanuts. Author’s collection.

Thought experiments

The Kachikally Museum consists of a series of small circular huts with conical roofs, connected by a portico and scattered throughout a garden. It’s in Bakau, the first neighborhood you encounter along the Atlantic coast when leaving Banjul. This architectural motif, a parodic version of a hypothetical village designed for foreign visitors, is quite popular in this part of Africa. I’ve found it in several of the places I’ve stayed during these weeks and tourists seem to love it.

Each circular room is decorated with portraits of more or less well-known figures from the country’s history, painted directly on the white plaster of the outer wall. However, the real attraction of the place, the one that brings tourists in large jeeps from coastal hotels, is a pool of water where five or six particularly docile crocodiles bask in the sun. Under the bored gaze of a couple of local guides, they take turns petting them. Fortunately, I’m here during the low tourist season. There are few visitors, and I reach the garden on foot, walking through a neighborhood filled with single-story houses.

According to a story that everyone in Bakau tells, the original village is said to have grown around this holy crocodile pool. Only much later did the area on the windy cape, overlooking the mouth of the Gambia River on one side and the open ocean on the other, became a sought-after destination. First for the private residences of colonial administrators, and later for resorts catering to foreign tourists.

In the first room of the museum’s small ethnographic collection, an introductory panel, printed on a laminated sheet and affixed with four staples to a wooden board, opened with a phrase that stayed with me: "Gambia is a small fragile country." This was followed by generic information about the physical and human geography of the country, the kind that hardly captures attention. Perhaps, after the grand narratives of the large African countries I had visited in the previous months, those two adjectives—"small" and "fragile"—struck me for their almost yielding nature. The phrase lingered in my mind for the rest of my journey.

I found myself wondering to what extent the subdued image of Gambia, reduced to a thought experiment and shaped by colonial narratives, remains embedded in the country’s collective imagination more than half a century after independence. How much of that image still informs the way Gambia tells its own story today?

Fig. 3: View of the Atlantic coast from Bakau.

Fig. 4: The Arch 22 and the stands behind it on Independence Drive, Banjul.

Switching sides

When the British administration in Gambia decided to establish a capital city for the territories adjacent to the banks of the Gambia River, the most obvious choice was to settle at the river's mouth, where it flows placidly into the Atlantic Ocean. The bias toward the coast is a typical feature of colonial interventions, and territories like these, viewed by European administrators and traders primarily as extended outposts for river and ocean trade, were no exception.

Some doubt must have arisen over which of the two banks would be the most suitable. On the left bank, the southern one, a trading outpost with a dozen shacks had been set up on an island originally called Banjul, later renamed St. Mary's Island by the British. On the opposite bank, a strip of land along the coast—the "ceded mile"—had been secured by colonial administrators to prevent any interference with trading vessels heading into the interior. This side of the river had a more prominent history of trade encounters, being the ‘land of the seven villages’ in the prestigious Kingdom of Niumi. However, at the time, history and prestige were deemed less important than the ability to manage the growing commercial traffic without disturbance, and the choice fell on Banjul.

Given the size of the river at its mouth—which, even today, despite much improved transportation, still constitutes a significant barrier—the decision to establish the new colonial capital city on the southern shore marked a watershed moment in the history of the two strips of land on opposite banks of the river. From then on, St. Mary’s Island, where the colonial settlement of Bathurst, named after the Secretary of State for the Colonies at the time, was established, and its hinterland, connected by extensions of marshy terrain, developed into the most populated areas of the country. A couple of centuries later, it's no coincidence that most foreign visitors, myself included, begin their journey right here.

Fig. 5: Historic architecture in Banjul, Gambia National Museum.

Fig. 6: A barge in the Banjul port.

Fig. 7: The entrance to Fort Bullen, Barra.

A few days after my arrival, I took the ferry to cross to the northern shore, to Barra. My timing was not very fortunate. On the very day I chose for the crossing, a diplomatic meeting was scheduled at the Barra port, and the president, along with his large entourage, was traveling on the same boat. As partial compensation for the many hours of delay spent under the scorching sun, I got to witness the entire boarding ceremony, complete with armored vehicles and red carpets. During the crossing, I amused myself watching the fast motorboats filled with security personnel nervously circling the slow ferry, repeatedly pushing away unaware small wooden boats, loaded with goods and passengers, that regularly cross this stretch of sea at the river’s mouth.

Barra is small and, outside the bustling market area next to the ferry terminal, it is calm. On the farthest tip of the town stands a fort, built in the first half of the 19th century. A friendly couple, the caretakers of Fort Bullen, let me wander inside and take a few photos from the well-preserved towers, adorned with rusted cannon batteries. The view is beautiful, there’s absolutely no one around, and I read the brief descriptions provided for visitors. The history of the site is told in a way that celebrates—perhaps overestimates—its role in the British anti-slavery campaign in the area. Almost no mention is made of the fact that the fort, like many others dotting the West African coast, primarily served to protect trade routes and, consequently, the commercial interests of the various colonial powers that succeeded one another in these territories.

Next to the fort, I notice the colorful workshop of a boat builder. The boats are so vividly decorated that I initially think they must be intended for some special festivity. Only later, on my way back, do I realize that they are the same boats that, overcrowded, cross multiple times a day towards Banjul.

Fig. 8: A boat workshop in Barra.

Fig. 9: Unloading passengers.

Upriver

I munch on roasted peanuts constantly during these weeks. They are found almost everywhere at roadside stalls, sold in plastic bottles or in convenient walking portions wrapped in thin plastic bags.

As soon as you cross the Denton Bridge, which connects Banjul Island to the mainland and Bakau—after passing over a secondary stretch of water at the border between the river and the ocean, crowded with fishing boats and moored barges—you see large peanut processing plants lining both sides of the road. In search of other traces left by the groundnut production cycle on the built and natural landscape, I traveled upriver, passing through areas that have since developed into commercial outposts.

Fig. 10; 11; 12: GPMB warehouses and machineries in Kuntaur.

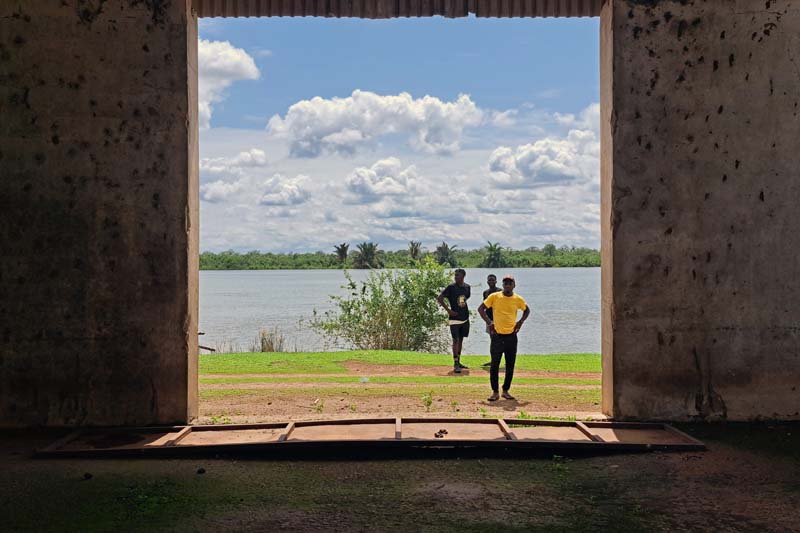

I arrived in Kuntaur, which the same document detailing the geographic unfolding of trade routes in 1950s Gambia described as the last major river port, allowing further inland access, beyond which only land transport is recommended. The area is known to non-local visitors for the large nature reserve on the opposite bank of the river and for one of the most famous archaeological sites of Senegambia, the Wassu megalithic stone circles. But the port area reveals another chapter of the recent history of this region. Among the various warehouses and industrial plants, the most imposing are those still bearing the inscription GPMB, Gambia Produce Marketing Board—formerly the Gambia Oil Seeds Marketing Board—an institution established in 1948 to stabilize the price of peanuts by purchasing directly from local producers at fixed rates. It remained a major player until the sector was privatized in the early 1990s.

A row of warehouses with large gates opens directly onto the river, now occupied—since the harvest season is still far off, as my guide assures me—only by a few goats wandering among the concrete slabs and metal pylons. Alongside are large machines for loading and unloading barges. Despite my guide’s vague reassurances, the entire complex appears underutilized. With the construction of two main roads on the north and south banks of the river, much of the transport of goods is now done by trucks, leaving riverside equipment like that in Kuntaur as relics of their former selves. 2

A little further on, a series of buildings with a style revealing their late colonial origin are spaced along a wide strip of land parallel to the river. A few small structures have been added over time, but the original administrative offices, staff accommodations, and communal buildings remain almost intact. Some of the bungalows are still inhabited. One of the buildings has been converted into a school, and, interestingly for a country with a vast Muslim majority, the small Catholic church, with a statue of Saint Anthony on the façade still appears to be in use.

Fig. 13; 14: Inside the empty groundnut storage rooms.

Fig. 15; 16; 17: Residential and communal buildings in the GPMB compound.

Janjabureh, on the other hand, is an island nestled further inland, where the river noticeably begins to narrow compared to its expansive size near the Atlantic Ocean. Here too, much like at Fort Bullen in Barra, the colonial narrative that casts the island as a heroic outpost of the British anti-slavery movement tends to overshadow and obscure the perhaps less emotionally charged but more historically accurate account of the settlement's primarily commercial role.

The long building surrounded by a wide veranda overlooking the northern branch of the river, which stands in front of the small ferry dock that I take every day to cross from the opposite bank, is remembered as a ‘slave house’. A footnote on the sign next to the building hesitantly admits that the structure most likely housed merchants, accountants, and perhaps goods that were part of the extensive network of trade exchanges that animated the banks of MacCarthy Island (as it was renamed in the early 19th century) for two centuries.

The grid of streets that once outlined Georgetown, the European settlement, is still perfectly recognizable. These streets were mainly occupied by the trading firms of the colonial period, such as the Compagnie Française d'Afrique Occidentale (CFAO) or the Maurel and Prom Company, but many of their houses, which doubled as shops and warehouses, now seem to be in a state of rapid decay. So much so that I find myself navigating through a streetscape that still evokes what must have been the atmosphere of the original commercial outpost, but has already significantly changed from the information I had gathered before arriving. And so, of the wooden house that was the only genuine trace testifying to the presence of the community of Liberated Africans who were sent in from Freetown in 1832, only the foundations remain after, as I was told, it completely burned down not long ago.

The grid of streets that once outlined Georgetown, the European settlement, is still perfectly recognizable. These streets were mainly occupied by trading companies during the colonial period, such as the Compagnie Française d'Afrique Occidentale (CFAO) or the Maurel and Prom Company. Many of the houses, which served as both shops and warehouses, now appear to be in a state of decay. Walking through the streets, I still catch glimpses of the atmosphere of the original commercial outpost, though much has changed since the information I gathered before my visit. For instance, the wooden house that stood as the only surviving testament to the presence of Liberated Africans, who were relocated from Freetown in 1832 3, has been reduced to just its foundations after it reportedly burned down not long ago.

Fig. 18; 19: The so-called ‘slave house’ in Janjabureh, a trader shop, warehouse, and house.

Fig. 20: Entrance to the ‘Georgetown’ Methodist church, one of the oldest in West Africa.

Fig. 21: The remaining of the wooden house who belonged to members of the community of Liberated Africans.

Fig. 22: The ruins of a trader shop in the center of Janjabureh.

Visible history

If this journey was motivated by the desire to continue my investigation of the physical and cultural landscapes, both current and past, of agribusiness in Africa, Gambia required me to deconstruct the way of seeing things that I’ve built over these past months. Perhaps it’s the history of this country, or maybe it’s simply the fact that, unlike oil palms, which are easily recognizable with their dense fronds in Congolese plantations, peanuts grow underground. Peanut fields have a far less distinctive profile. The image of this ‘one-crop country,’ which colonial practices and narratives helped to construct, may not lie in the vast, expansive plantations that visibly mark the landscape, in company towns, or in ambitious development projects.

In groundnuts production, the plants are small, with bright green leaves that form dense, compact clusters. Before harvest, the fields have a low, bushy appearance, resembling a sea of green with no sign of the peanuts themselves. The absence of large, visible agro-industrial plants in this country, especially as you proceed inland, and the small farms scattered across the countryside give the impression of dispersed production. It’s when you start recognising the small machineries for shelling peanuts and the collective granaries that are scattered across the landscape, when you come across large cargo barges and the increasingly frequent lines of trucks filled with peanuts wrapped in white sacks, that you are reminded of what this crop represents for the country.

In Tanzania, the idea of producing vegetable oil on a large scale for export is a late colonial-era concept, implemented with disproportionate and highly ineffective public investments. In Gambia, the development of groundnut production had a much more organic history and became deeply rooted in the country’s social structures. Although there were examples of ambitious agricultural development projects, such as the so-called 'Eggs Project'—the first major failure of the newly established Colonial Development Corporation, launched in 1948 and closed by 1950—Gambia did not have its own Groundnut Scheme.

Nonetheless, a phenomenon like that of ‘strange farming,’ a historical practice during the colonial period when seasonal non-native farmers, often from other regions or countries, were brought into or attracted to Gambia to cultivate groundnuts, has strongly shaped the country’s cultural identity. 4 These "strange farmers" were primarily migrants, often from neighboring countries like Senegal, Mali, and Guinea. They were unfamiliar, or "strange," to the local communities—hence the term—but made agreements with local communities to seasonally migrate, forming partially autonomous and temporary but recurrent groups and settlements. By making the area surrounding the Gambia River a crossroads for different ethnic groups, the rise in the demand for peanut crops indirectly contributed to the country's cultural diversity and its uniquely rich, layered cultural landscape.

As Jori Lewis points out in reference to neighboring Senegal 5, Gambia is not the only place affected by the establishment of this trade. However, in this country, it took on such a predominant role among economic activities that, in some ways, it makes Gambia unique. And yet, this heritage of trade encounters, cultural mixing, and migratory trajectories seems more difficult to communicate, and is thus obscured by narratives that foreground the unmediated contribution of the colonial actor. And the history of this ‘small and fragile’ country perhaps teaches us that an honest account of its encounters with both its constructed historical and natural landscapes does not require grand heroic narratives. Rather, alternative ways of telling these stories are no less rich, but they demand an exploration of approaches that still seem yet to be fully uncovered.

23 – Manual machineries for peanut shelling.

24 – A granary for peanuts in Lamin Koto.

[1] (1953) “Trading the Gambia”, Statistical and Economic Review: the United Africa Company Limited, n.11

[2] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/photo-story-cockle-farmers-chieftains-portraits-life-banks-gambia-river

[4] Sarr A. (2016), Islam, Power, and Dependency in the Gambia River Basin: The Politics of Land Control, 1790-1940, University of Rochester Press.

[5] Lewis J. (2022) Slaves for Peanuts: A Story of Conquest, Liberation, and a Crop That Changed History, New Press.