-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

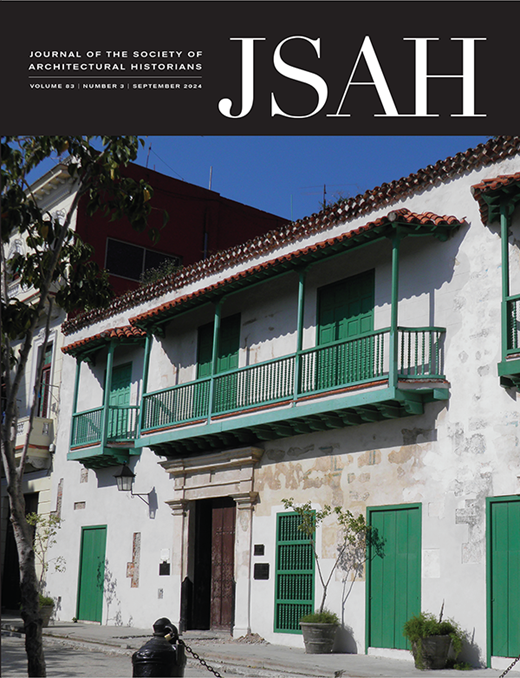

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Difference and Dissent in the American Landscape: Queering Northern Louisiana

Sep 24, 2024

by

Stathis Yeros, Recipient of H. Allen Brooks Traveling Fellowship 2024

Architectural historian and designer Stathis G. Yeros is the Mellon Fellow in Democracy and Landscape Studies, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C. His research focuses on LGBTQ+ spaces, critical urbanism studies and spatial activism. He is the author of Queering Urbanism: Insurgent Spaces in the Fight for Justice, forthcoming from the University of California Press. He earned a PhD in architecture and a Master of Architecture from University of California, Berkeley.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, will spend three months travel the U.S. Deep South to collect evidence of queer and trans social life in the physical environment of a region where queer people’s rights have historically been repressed and are currently under attack. He plans to partner with LGBTQ+ nonprofits and university departments in the region to organize six workshops for local LGBTQ+ people to share their stories and views about what constitutes queer space.

______________________________________________________________________

The recent controversies surrounding drag shows, transgender participation in sports, and the teaching of queer history in the Southern United States highlight a persistent struggle over the true access that public spaces afford to queer and transgender people. Despite the broad international recognition that LGBTQ+ cultural producers have achieved, significant parts of American society still perceive certain bodies—particularly those of queer, transgender, and non-binary people of color—as “too risky” to be allowed into public spaces. These conflicts are contemporary expressions of the longstanding racial, class, and gender tensions that have shaped LGBTQ+ movement history from the 1950s to the present.

While legal advancements have expanded the national body politic to include queer and transgender people as members of the broader community of citizens, it remains less clear how these legal frameworks and discourse about LGBTQ+ rights foster local attachments in the Deep South, where hostility and discrimination against LGBTQ+ people are often part of everyday life. The Deep South, stretching from South Carolina and Georgia to the Florida Panhandle, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, coastal eastern Texas, and parts of Arkansas and Tennessee along the Mississippi River, is a region deeply shaped by the history of slavery, segregation, and the civil rights movement. It is also home to nearly one million LGBTQ+ people.

In August 2024, I embarked on a three-month journey through the Deep South to explore spaces where queer and trans people have historically built social and political networks, engage with as many individuals as possible, and observe LGBTQ+ festivals throughout the region. My aim is to document these spaces and record my observations, capturing a snapshot of queer and trans life in the United States during a period of significant social change and political turmoil. My broader goal is to investigate how LGBTQ+ cultures have historically intersected with race and class divisions to create a landscape of political dissent, and why lateral connections across experiences of marginalization and dispossession have often failed to build broader coalitions. I believe that understanding this landscape is crucial for addressing the deepening polarization in American society. This and the subsequent two “dispatches from the queer South” will chronicle my raw observations and reflections on the road, laying the groundwork for later analysis.

My journey begins in Louisiana and Mississippi, where I focus on three types of spaces: entertainment and socializing venues, domestic spaces, and sites of service and advocacy, including medical clinics and protest sites. The first category encompasses both commercial spaces, such as bars, clubs, and bookstores—historically the most visible manifestations of queer life—and nonprofits like community centers. Before arriving in Shreveport, the first stop on this journey, I spent a week delving into the rich collections of LGBTQ+ material at Georgia State University and the Georgia Historical Society in Atlanta. Leafing through newsletters, magazines, private correspondence, and photographs dating back to the 1950s—a generous gift from the first generation of openly queer Americans who deliberately created a historical record for those of us who now take some of this history for granted—I realized that a key characteristic of queer spaces is their impermanence. For a long time, much of queer life happened behind closed doors. These interiors evolved over time, shaped by new leases, new tastes, and what Foucault might describe as new “economies of pleasure.” But queer life also thrived in rural retreats and annual festivals that were embedded in the local economies where they took place, adding complexity to the work of historians of the built environment. With this journey, I aim to follow the archival traces wherever they may lead me.

From Shreveport with Love

Shreveport, Louisiana, was founded in 1836, a year after the Shreve Town Company—a corporation established to develop a trading post along the newly navigable Red River—coerced the Caddo Indians into selling their land during the period of Indian Removal, a tragic chapter in U.S. history marked by the forced migration of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories. Incorporated as a city in 1871, Shreveport emerged in a landscape dominated by plantations stretching to the Gulf Coast. The city's urban economy was deeply intertwined with the legacies of slavery, sustaining a highly stratified society where former slaves continued to labor on the estates of wealthy landowners well after the Civil War ended in 1865 and through the Reconstruction era (1865-1877).

The discovery of oil at Caddo-Pines in 1905 rapidly led to the formation of an affluent urban class, whose influence is still evident in the material culture of Shreveport’s older neighborhoods. Oil wealth financed the construction of mansions, parks, churches, and public buildings that, despite the decline of the city’s single-sector economy since the 1970s and the oil crash of 1985, still imbue parts of the city center and surrounding residential areas with a lingering air of opulence that caught me by surprise as I drove into the city. I knew that the population had been steadily declining since the 1980s, and much of the national press coverage focused on Shreveport’s high rates of violent crime, which had earned it an unenviable spot among the most dangerous cities in the United States. However, the story that crime statistics tell is, at best, limited—and at worst, it is a tool of controlling the most vulnerable, masking over a century of systematic oppression and inequality.

Today, Shreveport is positioned almost equidistantly between Dallas, Texas, and Jackson, Mississippi, along the East-West Interstate 20. I drove for three and a half hours from Jackson, a stretch of highway with very few pit stops in small townships that, as I later discovered, had a queer history as cruising areas—integral parts of a rural sex landscape in their own right. My time in the city was limited, so after dropping my bags off at a bed and breakfast, I immediately set out to explore the local gay bars.

Before the Internet era, planning a night out often meant relying on the trusted Bob Damron Address Book, a gay guidebook first published in 1964. These guides were a cornerstone of LGBTQ+ travel and socializing across the United States, though their significance waned in the last two decades until the last print edition of 2021. Mapping the Gay Guides, a digital humanities project by Amanda Regan and Eric Gonzaba offers a vivid illustration of the changing American LGBTQ+ social landscape, revealing shifts in movement and culture over time. Gay bars, which dominated the listings in these guides, highlight their central role in LGBTQ+ socializing. In Shreveport, the number of gay bars and clubs fluctuated slightly, from one bar listed in the 1965 guide to three in 1988, alongside two cruising areas and a bookstore that made the list.

During my own online search for LGBTQ+ nightlife in Shreveport, I found two options: Central Station, a gay club, and Korner Lounge, a bar that first appeared in Damron’s guides in 1965. Both venues are located in the downtown within a block of each other. I confirmed my plans with Sam [pseudonym], a local resident, graphic designer, and gay activist who provided valuable insights on where to go and what to expect. Since I arrived on a Wednesday evening, my options were limited, as weekends offer more opportunities for pop-up parties at queer-friendly venues around the city. However, no such events were scheduled during my brief stay. Sam explained that many queer Shreveport residents of his generation (he was born in the early 1990s) sought alternative spaces to meet, which led a few friends who grew up in the city to establish ShrevePride in 2019. This organization advocates for inclusive queer spaces through fundraising and hosts events like Q-Prom in June, a themed yearly party that reimagines the quintessential American social experience. In April, ShrevePride organizes Field Gay, a day of outdoor games, competitions, and revelry in a city park. However, for the time being, the downtown bars had to be my window into Shreveport’s queer social life.

Central Station is housed inside a former train station, a unique setting that lends an air of historical significance to the space. The entire building is occupied by the club, situated just beneath a highway overpass with an abandoned train wagon parked nearby, adding to the raunchy, industrial yet nostalgic atmosphere. The building retains many of the original trappings of a train station, including a grand entrance that now faces a four-lane street. But club access is through a door in the parking lot at the back of the building, opening directly into one of the three dance floors—four, if you count the rooftop bar that is open when the weather allows it. When I visited, during a trivia game night, only one section of the club was open. I asked the young lesbian bartender, a student at Louisiana Tech, if I could take some photos. She glanced at a man sitting at the bar before cautiously replying, “Sure, but no people should be recognizable in the photos.”

The interior is nothing out of the ordinary. In fact, it is reminiscent of many clubs I have visited across the country. The description could apply to any number of LGBTQ+ spaces: dim lighting, a mix of retro and modern decor, and an unmistakable sense of familiarity. What stood out more was the façade—the back side of the train station, now the front of the gay bar—lined with a variety of flags. The American flag flew alongside the rainbow flag and the trans pride flag, while the parking lot was filled predominantly with pick-up trucks by the time I left. This caught my attention, given that sedans and SUVs, often associated with white-collar jobs and families, were more common in city streets. While I don’t want to draw too strong a conclusion based on limited observation, I made a mental note to pay closer attention to intersections of LGBTQ+ and signifiers of working-class life.

Figure 1. Central Station exterior street façade. The building used to house a train station. The club entrance is now from the back side, where the parking lot is also located.

Figure 2. Central Station’s current entrance and parking lot with an abandoned train wagon visible in the background.

Figure 3. Central Station interior. The decoration is typical of gay clubs around the country.

Central Station has a history of catering to a diverse clientele, hosting events ranging from drag shows to karaoke contests. For fans of RuPaul’s Drag Race, it’s worth noting that Shreveport is the hometown of Chi Chi DeVayne, the beloved Southern queen who tragically passed away at age thirty-four in 2020. Since then, Central Station has held an annual memorial to honor her life and contributions to the community. The ability to host a variety of events is a hallmark of LGBTQ+ spaces, which often serve as both social hubs and places of refuge, adapting to the needs of their patrons. Much has been written about the importance of physical spaces for queer socializing, even as online cruising and dating have transformed everyday patterns of LGBTQ+ life. Faced with stiff competition from more mainstream, gay-friendly clubs, explicitly gay venues strive to connect with different groups within LGBTQ+ communities by offering diverse programming. Drag performances are a key part of this, as are the more niche aspects of gay club culture, like leather events. On the practical side, gay clubs are businesses, and to sustain a large venue in a city where the openly gay population is smaller than in larger American cities, they must be open to hosting a wide range of events.

Two blocks away from Central Station is the Korner Lounge, a bar with a rich history that dates to its origins as a diner in the 1920s. Its first liquor license was issued in 1933, the year Prohibition ended in the United States, suggesting it may have operated as a speakeasy within the diner before then. At some point, the bar was separated from the rest of the building with a wall, occupying the corner of Louisiana Avenue and Cotton Street on the outskirts of the city center. The Damron Guides list it under the names Korner (from 1965) and Bobby’s Korner (1970-1989). A small black star next to the listing indicated that it was a “very popular” hangout. In 1976, Damron also gave it an “OC” designation, meaning it attracted an “older/more mature crowd,” which it retained for a year before being reclassified as “RT,” indicating “Raunchy Types – Hustlers, Drags, and other ‘Downtown’ Types.” That designation was removed in 1984. The bar’s narrow space features a bar along one side, a small podium that functions as stage fitting a single person at the end, and a backroom with three slot machines (gambling is legal in Louisiana, and most gay bars I visited in the state had at least a few slot machines). The lack of windows, common in gay bars before 1980, added to its air of mystery.

Figure 4. Exterior view of the Korner Lounge. The building dates to the 1920s and was originally a diner. It has operated as a bar since the end of Prohibition in 1933 and as a gay bar at least since 1964.

Figure 5. Korner Lounge's interior with a small stage on the far left and a back room with slot machines.

Despite the absence of windows, gay bars have historically been conspicuous. The risk of being seen entering or exiting was always present, posing dangers not only from homophobic violence but also from legal threats. In 1965, the bar’s owner, listed as Miss Bobbie R. Thomson, received a letter from Barksdale Air Force Base near Shreveport which prohibited airmen from entering the bar, indicating that it was already a known gay hangout. (The bar’s history is narrated in the independently produced 2024 documentary Closet 2 Pride, directed by Robert Darrow and David Hylan that also includes important testimonies by key figures in the city’s queer history and present activism). Same-sex sexual activity was illegal in Louisiana until the 2003 Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas, and police raids were not uncommon. In New Orleans, where the gay scene has been visible but politically weak for most of its history, the persecution of homosexuality ended with a city nondiscrimination ordinance a little earlier, in 1991. It’s unclear whether the well-documented practice of gay bar owners bribing police applied in Shreveport, but it was certainly common in New Orleans and other cities.

Robert Darrow, a local gay political activist and longtime figure in Shreveport’s gay culture, told me that the Korner’s straight owner in the 1970s bought it from its earlier lesbian owner and ran it as a mainstream, straight bar during the day. However, when her younger brother, a Vietnam War veteran, became the evening bartender, its queer legacy was revived. The brother, Bobby, was gay, and so was the clientele after heterosexual office workers finished their happy hour drinks and left.

One of the questions I asked my contacts was how racial divisions shaped queer socializing in the Deep South. Anecdotally, the bars I visited in Shreveport and elsewhere (except for New Orleans) were predominantly populated by white people. While this may be a skewed view based on limited data, there is a well-documented trend of racial separation within the gay community. One of my interlocutors, who operate a gay bar in the 1980s, confirmed this, noting that when he ventured into the gay bar business after returning to Shreveport from a brief stint running gay nightclubs in New York City, his bar was initially frequented by white gay men. When black men began to visit in large numbers (which he welcomed), white patrons stopped coming. Racial integration proved difficult to achieve, and the bar closed after only a few years. My observations in other cities with similar population and socioeconomic conditions, including Jackson and Hattiesburg, Mississippi, support this reality. In Hattiesburg, for example, it took me some time to realize that black queer nightlife operates in separate spaces from the more mainstream—and publicly visible—LGBTQ+ scene. This was partly due to my own identity as a white gay man and the fact that the black queer club I eventually visited was not explicitly designated as such (I will discuss Mississippi’s queer landscape in my next post).

During the last decade, public LGBTQ+ life in the Southern cities I visited is much more visible than even a decade ago, despite racial divisions that persist in many ways. Flags, posters, and occasional murals celebrating queer cultures are a testament to this visibility. Shreveport is a prime example. Three murals near Korner Lounge and Central Station mark the area as LGBTQ+ friendly. One mural on Korner’s back side, facing the parking lot, features the word “love” repeated thirteen times, though it lacks overt queer iconography. Another, more recent mural titled Ascension Underpass was painted in 2022 by Ka'Davien Baylor, Ben Moss, Eric Francis, and Willie A. Love as part of a community project funded by the Chamber of Commerce. Although largely abstract, the mural prominently features butterfly shapes, which are symbols of renewal and trans embodiment. Trans inclusion is even more explicit in a third mural on the wall of the Uptown Bar and Lounge, a black club and social space that, while not specifically an LGBTQ+ venue, appears to be queer-friendly. Though I was not able to verify my interpretation by talking to the mural’s creators during my visit, I read it as a powerful message of transformation and LGBTQ+ pride, highlighted by raised fists painted in rainbow colors.

Figure 6. Mural on the side of Korner Lounge highlighting the word “love.”

Figure 7. Ascension Underpass mural created by Ka'Davien Baylor, Ben Moss, Eric Francis, and Willie A. Love in a highway underpass in downtown Shreveport. The butterfly motif denotes transformation and is often used as symbol of trans embodiment.

Figure 8. Mural on the side of Uptown Bar and Lounge in downtown Shreveport showing a scene of transformation and what I interpret as trans/queer empowerment conveyed from the contrast between the black and white and colorful sections.

Sam, my local guide, pointed out this iconography as part of a broader effort by the city government to revitalize the downtown. He also led me to another mural that welcomes visitors to Shreveport, though its location in an otherwise quiet area with office buildings makes me question its effectiveness in promoting the city’s diverse cultures. The mural, created by Whitney Tates, Ben Moss, Linda Moss, Ka'Davien Baylor, and Lindsey Simpson, spells out “From Shreveport with Love,” with each letter depicting a different scene. The second “R” features two hot air ballons with the colors of the trans pride and rainbow flags—a subtle nod to LGBTQ+ cultures.

Figure 9. From Shreveport with Love mural in downtown Shreveport created by Whitney Tates, Ben Moss, Linda Moss, Ka'Davien Baylor, and Lindsey Simpson.

Shreveport’s official embrace of LGBTQ+ visibility ties into the idea of the so-called creative economy—the notion that open, socially progressive, and diverse neighborhoods attract a cosmopolitan workforce, including gays and lesbians, who help stimulate economic growth and make cities more competitive globally. Urbanist Richard Florida popularized this concept in the 1990s, but it has since faced criticism, along with scholarly research linking the creative economy to gentrification. Despite the city’s (admittedly mild) recent celebration of diversity, the lack of resources for economic revitalization in downtown Shreveport remains evident beneath the colorful veneer. The late-capitalist approach to city management has led to the demolition of public housing, contributing to gentrification in nearby residential neighborhoods and a shortage of affordable housing for lower-income residents. (This is a complex topic that I am not developing in this post, but how gentrification operates in Shreveport and similar cities is an important area of further study.)

I also noticed significant differences among the cities I visited. For instance, queer life in Jackson, Mississippi’s capital, and smaller cities is less visible than in Shreveport. However, vibrant queer communities thrive online throughout Mississippi and Louisiana, projecting a vision of queer spaces that sometimes contrasts with physical reality. Moreover, a quick glance at Damron guides since 1990 shows that the number of gay bars has decreased, but despite predictions of their demise bars have not disappeared entirely. However, the changing Southern queer landscape has created a need to preserve the history of these spaces as community institutions. Maigen Sullivan and Joshua Burford founded Invisible Histories, an archival project based in Alabama, to undertake this work. With the help of Catherine Cooper, who is based at the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training in Natchitoches, Louisiana, they have begun creating digital reconstructions of significant gay bars that are on the brink of closing, starting with a bar in North Carolina.

Back at Korner Lounge, when I arrived around 6:30 PM the bar was empty except for a regular at the slot machine. The bartender, who had spent most of his life in Dallas, greeted me warmly as I walked in. I hadn’t planned to stay, but the welcoming atmosphere convinced me otherwise. I ordered a drink, and we soon struck up a conversation. A friend of his, stopping by for an after-work drink, joined us. With just the three of us at the bar, I found myself drawn into their conversation. When the topic turned to politics, the friend mentioned that she had voted for Trump and intended to do so again. The bartender scoffed, and I quickly clarified that I was there as an observer, not to discuss politics. But that proved easier said than done.

If the Wallpaper Could Speak

The next morning, while savoring a hearty Southern breakfast, I struck up a conversation with Tom [pseudonym], a gay man who had grown up in Shreveport. He shared stories about the city's history and his experiences growing up gay in an Armenian-American family with Italian roots. The bed and breakfast where we met occupies a two-story house built in 1870, characteristic of the affluent neighborhood where it was built—a neighborhood now rapidly gentrifying after a period of decline. The decor is an eclectic blend, combining elements that reflect both local traditions and broader cultural influences. I had chosen this accommodation partly because I suspected it might be gay-friendly, and sure enough, when I mentioned my research topic at the breakfast table both locals and visitors had much to share. I was particularly curious to find out more about the origin of the bed and breakfast’s decoration and what my interlocutors thought about it. Much of the decor evokes old Hollywood, which, as I found out, harkens back to the owner's family ties in Southern California. The owner is also a collector of Louisiana painters and European antiques, creating a space that feels both cosmopolitan and deeply rooted in the aesthetic traditions of the Deep South.

Figure 10. The interior of the bed and breakfast where I stayed in Shreveport reflecting its owner’s eclectic taste. decoration of the bed and breakfast where I stayed in Shreveport.

Figure 11. The dining hall with a painting of a male figure in a Mardi Gras costume framed by two vases above the fireplace.

Tom, a longtime Shreveport resident, who is white, told me that he felt at home in this environment and that although he has never had to formally come out, his homosexuality was accepted by everyone within his social circle. He spoke with a mix of wonder at how times have changed and pride in his family when he recounted how his nephew recently came out publicly and boldly to his father—my interlocutor’s brother—and was met with immediate acceptance. He also observed that the South has always had a touch of queerness, evident in the region’s extravagant decorations and fashion choices for both women and men. I expressed a genuine praise for the interior design and the art collection that filled the room where we had breakfast, even as I quietly reflected on the power dynamics inherent in the grand, nostalgic world this design sought to recreate.

A little later, another local, Lauren [pseudonym], joined us for breakfast and sat next to me in the dining hall. We struck up an easy conversation about travel, wellness, and interior design. When she heard about the purpose of my visit to Shreveport, Lauren shared memories of growing up with her aunt just a few blocks away—a “traditional fag hag,” as she put it in a hushed tone, who was always surrounded by gay people. Lauren associated that time with cocktail receptions, beautiful outfits, and lively conversations. Then, seemingly out of the blue, she lowered her voice again to tell me that the cook who prepared our breakfast came from a family of former slaves. The cook's family had lived on a nearby plantation, and when the owner passed away, he left instructions in his will that the land should be distributed among the tenants who lived there (a term used for former slaves who, after the Civil War, worked the land as nominally free laborers but were denied the means to accumulate wealth). Despite owning land, the cook still worked in the kitchen. There was no mention of the lack of intergenerational capital, without which land ownership loses much of its significance. It turns out that the lavish lifestyle of Lauren's aunt, who lived down the street, was also supported by slave labor.

This conversation lingered in my mind as I later visited Oakland Plantation near Natchitoches, now a National Park. During the Reconstruction era, plantation owners could pay tenants with any currency they chose. In this case, the owner printed his own currency, which was accepted only at the general store on the property that he owned, but nowhere else. The plantation, preserved as it was in the late 1960s, served as a stark reminder of the enduring legacy of slavery that shaped Southern life well into the twentieth century—a legacy that, like the underlying conservatism within the LGBTQ+ community, is never far from the surface.

Figure 12. Interior of the General Store at the Oakland Plantation near Natchitoches, Louisiana as it was in the 1960s, now part of the Cane River Creole National Historic Park.

Figure 13. A slave/tenant cabin in the Oakland Plantation near Natchitoches, Louisiana, part of the Cane River Creole National Historical Park.

Silence = Death

On my final day in Shreveport, I visited The Philadelphia Center, Northwest Louisiana’s AIDS resource center. Established in 1991, the Center provides HIV prevention services, an AIDS clinic, and other support services for people living with HIV and their families. The Center was founded through the activism of Marc Spurlock, a doctor at a local hospital and a member of ACT UP, and Robert Darrow, who served as the first executive director. Under their leadership, the Center secured federal funds through the 1990 Ryan White CARE Act, which allocated federal resources for HIV care and treatment services for low-income individuals. When I spoke with Darrow, he recalled his public disputes with the “Catholic hierarchy” in the local press, where he advocated for condom use despite the Church’s opposition. Nonetheless, the Catholic-affiliated Schumpert Hospital in Shreveport offered space on their campus for the Center, recognizing its humanitarian mission. The hospital had already been running a hospice, Mercy Center, which they later transferred to The Philadelphia Center’s purview. Eventually, Schumpert purchased the building where the Center is now located and gifted it to the organization, which now owns it outright.

Figure 14. The entrance to The Philadelphia Center, an HIV/AIDS clinic and resource center in a low-income residential area in Shreveport.

Figure 15. Mural painted on the side of The Philadelphia Center.

The building, now named after Darrow, was previously used as a dental clinic. The transformation is remarkable. During my visit, the Center buzzed with activity. The spacious waiting area was furnished with couches, chairs, and floor lamps that softened the harsh fluorescent lighting and clinical acoustic panels. A display case of Mardi Gras memorabilia served as a tribute to a longtime Center employee. The bulletin board featured up-to-date announcements and a poster introducing the Center’s syringe exchange program, a new initiative that is part of the historically controversial harm-reduction approach to HIV prevention for intravenous drug users.

The hallways are adorned with works by local artists, many of which explore themes of queerness. Corinne [pseudonym], guided me through the building and generously shared insights into the center’s current work. She explained that one of the goals of the displayed art is to create an environment where people feel at ease and can reflect on their sexuality. Near the laboratory, a painting of a naked torso serves as “eye candy,” as she put it, for those nervously waiting to have their blood drawn. A refreshing approach to the value of art in everyday life. One of the most touching pieces is a large white canvas with a red ribbon—a global symbol of AIDS awareness—signed by over a hundred people whose lives have been touched by the Center, some of whom came from as far away as Florida, Texas, and Mississippi. (I do not include a photograph of the artwork and of other Center memorabilia because many names and signatures are recognizable).

Figure 16. Art hanging on the wall near the entrance to the laboratory at The Philadelphia Center where clients wait to get their blood drawn.

Corinne emphasized that the staff approach everyone with empathy, allowing homeless clients to wash clothes and use the—deliberately gender-neutral—bathrooms. The nontraditional use of the bathrooms sometimes leads to plumbing issues, but as Corinne matter-of-factly stated, “If someone has nowhere else to go, the Center cannot close its doors on them. Center staff ask everyone to respect the building because, otherwise, they may lose their license to operate, and everyone would lose access to it.”

I was struck by the absence of defensive architecture, such as window rails or blinds, often used to obscure views and separate spaces in similar facilities. While there was a security camera at the entrance and visitors needed to be buzzed in, the rooms at The Philadelphia Center were filled with sunlight from large unobstructed windows—a deliberate choice by the staff to create an inviting and calming environment. Both Darrow, who has since passed the baton to a new generation of organizers, and Corinne noted that the center has enjoyed strong support from the local community since its inception.

Many gay men had moved to the Highland neighborhood close to downtown, where the Center is located, during the 1970s and 1980s in part because of the affordable rents. This community was devasted during the AIDS epidemic, but Highland remained gay-friendly and low income. Even today, as Darrow, who kept meticulous records of the residential addresses of the Center’s clients, pointed out, many of them live in and around the neighborhood. This is part of the reason why, when the Center planned a recent expansion, they decided to stay nearby. The organization has just completed construction on a renovated building a few blocks away, set to open in 2025, which will provide additional office space for case managers and reduce waiting times for emergency care. Like the original building, this new clinic is fully integrated within its residential surroundings. The Center’s team had to push back on some of the architect’s initial choices for interior finishes, including a color scheme of blacks and reds. Corinne explained that while the design was aesthetically strong, and “on a good direction,” it was “not a good direction from the perspective of making visitors and clients feel welcome, relax, and be able to get out whatever they needed to get out with their case manager.”

The Philadelphia Center grew out of a pioneering chapter of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), founded in Shreveport in 1989 by Gary Cathey, Chuck Selber, and Joe DeSantis. All three were Shreveport natives who had returned from stints in New York and California, where they had been involved in AIDS activism. They were soon joined by a small but vocal group of local activists, including women and straight family members of people with AIDS. ACT UP, founded in New York in March 1987, is best known for its public demonstrations in larger cities with long-established gay rights movements. Its motto, “Silence = Death,” became a rallying cry for a generation of gays and lesbians who developed their political consciousness during the AIDS crisis. The Shreveport chapter, whose story is told in the excellent 2017 documentary Small Town Rage: Fighting Back in the Deep South by David Hylan and Raydra Hall, is a remarkable example of the resilience of a small group of passionate advocates who fought for the rights of gay people and AIDS patients in the face of opposition from the medical establishment, city leaders, state government, and even the Ku Klux Klan.

Their rage and determination were fueled by the inhumane treatment of AIDS patients in local hospitals, where nurses and doctors often refused to treat them, sometimes even neglecting to feed them for fear of entering their rooms—despite the fact that the transmission of HIV was well understood by physicians by that time. Ignorance, stigma, and moral condemnation by the church only intensified their anger and resolve. Photographs from ACT UP meetings and demonstrations reveal that almost all members were white, which is consistent with what we know about ACT UP chapters in New York and elsewhere. This doesn’t mean that black people didn’t engage in AIDS advocacy, but rather likely reflects the deeply rooted racial separation in LGBTQ+ life at the time. Nonetheless, the leaders of ACT UP Shreveport proved to be effective messengers, and The Philadelphia Center has grown into a racially diverse organization that serves an equally diverse client base.

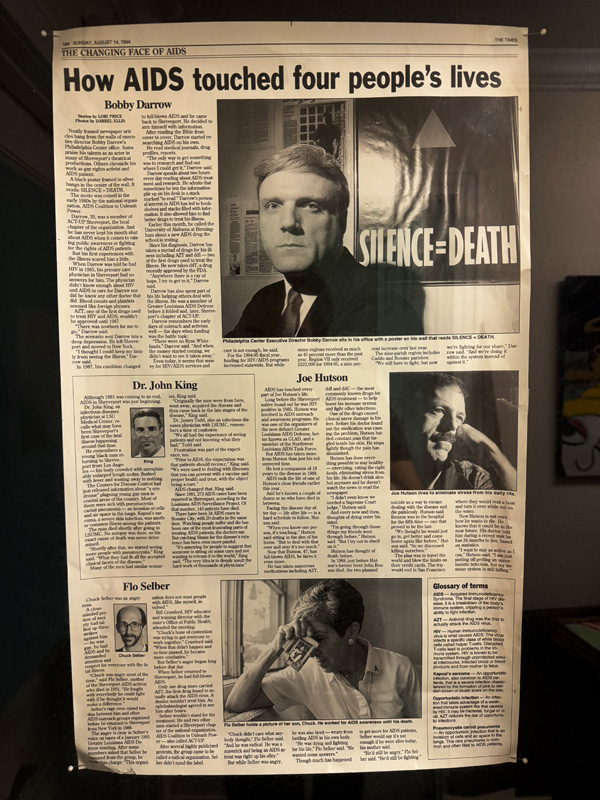

Figure 17. Newspaper article about ACT UP published in August 1994 in Shreveport Times with a photograph of Robert Darrow now hanging at the Philadelphia Center.

This work is far from finished. Over the next two weeks, I traveled through Mississippi, where I observed the day-to-day challenges faced by similar medical clinics, community centers, and shelters for LGBTQ+ people experiencing homelessness. The most striking example of the urgency to highlight the transformative work of these organizations occurred in Hattiesburg, where I had planned to visit a clinic catering to transgender people. This clinic, offering transgender-affirming care, operates out of a pale blue converted residential building on one of the city’s main thoroughfares near the University of Southern Mississippi campus. I had contacted members of the staff and planned to visit on my first day in Hattiesburg. However, I hadn’t heard back before my arrival, and when I drove to the address, I was met with a “For Sale” sign posted in front of the entrance. I later found out that the clinic had to close its physical space due to anti-trans provocateurs recording patients and guests who were visiting the building. The involvement of the FBI in this case and the escalating threats against similar clinics underscore the dangers faced by organizations that serve transgender people in hostile environments. As the rates of trans murders and suicides continue to climb, their erasure from public life—and from physical spaces—inflicts ongoing harm.

Figure 18. The Spectrum Center, an LGBTQ+ community center where regular social gatherings take place and provides emergency shelter for queer and trans youth in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. The Center is in a residential neighborhood near a Planned Parenthood clinic. I am not showing images of the former site of the transgender clinic mentioned in the text, which is the subject of an FBI investigation about right wing anti-trans agitators.

This leg of my journey concluded in New Orleans, a city with a rich and distinct queer history. Much like Atlanta, New Orleans is a crucial node in the network of queer life in the South. Its history, shaped by Mardi Gras and its unique race relations, sets it apart from other Southern cities. In 2020, two trans women of color, Mariah Moore and Milan Nicole Sherry, founded House of Tulip to provide “economic stability and safety through zero-barrier, permanent housing and pathways to education, healthcare, employment, and home ownership” to trans and gender nonconforming people in New Orleans. In the 2022 short documentary House of Tulip, directed by Cydney Tucker for TIME magazine, the founders explain that they began as a grassroots effort, meeting in each other’s homes and processing their grief from losing friends to senseless anti-trans violence. They determined that their priority was to create a safe space where black trans women could find temporary shelter and build empowerment.

Despite my best efforts, I have not yet been able to visit the space or connect with the current board. I respect and understand the reluctance of activists to engage with an outsider, particularly given the potential harm of extractive academic research. While there are no easy answers to the ethical challenges this poses, I have endeavored to build relationships that will extend beyond the scope of this project, guided by those on the ground in how best to support their ongoing work. Nevertheless, I remain convinced that uncovering the layers of queer history is crucial to understanding how the present is shaped by its silences, tragedies, and triumphs. New Orleans, with its vibrant cultural tapestry, stands as an essential case study—and the starting point for the next phase of my journey.