-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

2018 Cuba Field Seminar Report - Part Two

Day 7. Friday, December 7th, 2018. Firefighters, astronauts, and sunny beaches.

With our bags packed we boarded the bus towards Matanzas, an important port city and home of the famous Afro-Cuban band Sonora Matancera. The road (and Monty) had a surprise prepared for us, the incredible rest-stop Mirador de Bacunayagua with its striking concrete roof, delicious piña coladas, live music, and breathtaking views of the Yumuri Valley and the impressive bridge across it, the Bacunayagua Bridge, the tallest of its kind in Cuba.

Bacunayagua bridge

Bacunayagua Mirador

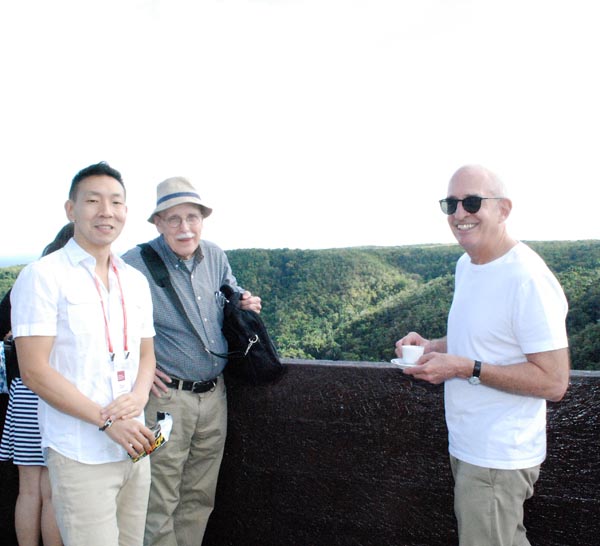

Dan, Paul and Monty enjoying the view

Linda, Susane, Pat and Julia sipping pina coladas

More of the Bacunayagua bridge

We continued our journey of the day stopping at Matanzas, where we walked around the historic center and visited a neoclassical fire station built early 20th century. Still active today, the fire station is also a museum where many firetrucks from different eras and historical artifacts related to Cuban firefighters are displayed. After that, we arrived in Varadero; we had lunch in Xanadu, a beach house designed by Govantes y Cabarrocas in 1926 for the affluent American businessman Irènee Dupont. Our next stop was La Casa de Los Cosmonautas, a house intended for relaxation, recreation, and the physical and psychological recovery of Russian cosmonauts. This building with its traditional architecture of gable roofs, red tiles, and white walls surprises its visitors when they realize it cantilevers spectacularly, almost like it’s floating and ready to take off.

Matanza's fire station

View from one of the windows at Xanadu

David and Dan enjoying the view from the Xanadu Mansion

After our visit to La Casa de Los Cosmonautas we checked in to our hotel, an all-inclusive resort in Varadero where we got to experience a couple of hours of delightful blue, sandy beaches, relaxing swimming pools, unlimited cocktails, and an overly exotic Cuban music show. I found it sad (the show, just the show; not the beach, swimming pools or sweet drinks) especially after visiting the art school and its prodigious students. I found depressing that this is the image of Cuba some tourist take home, especially with so many kids in the audience. In the end, three women dressed as Cohiba cigars were too much to take, I called it quits on the free cocktails and headed to bed.

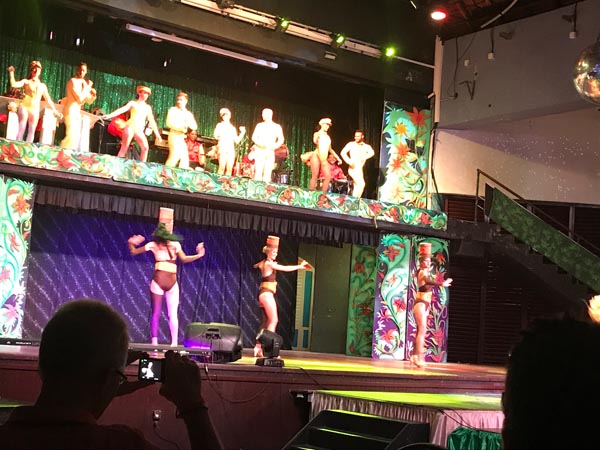

Dancers dressed as Cohiba cigars

Day 8. Friday, December 8th, 2018. Fading houses, plastic houses, and wooden houses.

Next morning, we continued with our trip; our first stop, Cardenas, was the perfect detox for the excesses we experienced in Varadero. Cardenas is a dormitory city for resort workers and a very modest town. Most of the houses here are faded and deteriorated, giving the part of town we visited an overall ruined atmosphere. While visiting the building that brought us here, the dilapidated yet beautiful Molokoff Market, I thought that any person staying in a resort in Varadero should take a day trip to Cardenas to experience the contrasting realities inside this sunny island.

Horse carriages are the main form of transportation in Cardenas

Molokoff Market

Cardenas shoemaker

Next stop: Cienfuegos. I was particularly excited to drive to Cienfuegos because on our way there we planned to stop in the Simon Bolivar Urbanization, a complex of 100 Petrocasas. Petrocasas, short for “petroleum houses,” are small dwelling units built from by-products of Venezuela’s oil refining industry, more specifically polymerizing vinyl chloride. Each set of houses ought to be close to a profile factory where the kits to build the houses are manufactured and packaged. This highly advertised “technology” consists of lost formwork in the form of rigid PVC panels which are fitted together LEGO-like, and inserted on a concrete base. Later the PVC panels are filled with concrete and steel and iron girders resulting in loadbearing walls, which make a steady structure. I’ve been studying Petrocasas in Venezuela, paying close attention to post-occupancy transformations and adaptations, and today’s stop in Cienfuegos was one of the reasons why I applied and was granted this prestigious fellowship. In my application, I mentioned that I was very interested in visiting this complex of plastic houses in Cienfuegos to compare it with the cases I’ve documented in Venezuela. SAH and Monty listened, not only by making it possible for me to be on the trip, but also including the petrocasas on the tight schedule and stopping the tour bus in the Simon Bolivar Urbanization to allow us to disembark, take pictures, and chat with some of the occupants.

I was flabbergasted to find so many significant differences between the Venezuelan and Cuban projects. First, here in Cuba, the project includes a playground, ample streets for car circulation and wide pedestrian boulevards with gardens and adequate lighting. Also, the pristine white houses came with a contrasting front garden with green grass, carefully manicures bushes, palm trees, and flowers, which are (today, 11 years after completion) impeccably maintained by governmental agencies. The houses, which are rather small, especially around the kitchen area, were slightly enlarged by an additional space. These added sheds were built with traditional concrete blocks and zinc roofs, all identical in shape and size but painted in different colors, which affords an orderly yet cheerful effect to the urbanization. Lastly, windows and doors were protected with uniform white iron grids for further security. These small additions significantly improve the quality of the overall project and answer to some basic needs left uncovered by the initial plan and default houses. Why are the Cuban petrocasas better adequate than their Venezuelan counterparts? In my perspective, these changes respond to a housing agency more attuned with people’s housing needs. At the same time, an authoritarian government where “democracy” is on hold, hires architects who are more attentive to honoring their profession and actually delivering quality housing. Without overlooking the Cuban administration’s many, many flaws, I must say that one thing they’re not doing is trying to win elections; hence, they’re not responding to clientelism nor the devastating effects of extreme corruption.

Simon Bolivar petrocasas urbanization

A kitchen built inside one of the added sheds

With my head spinning and my heart pounding after the petrocasas, it was time for lunch. Before moving on, I would like to thank Victoria and Monty again for their pedagogical generosity, also a heartfelt thank you to all the trip participants who patiently and attentively listened to me, asked insightful questions, and gave much appreciated feedback. I’m deeply grateful and humbled by your support. To finish our day, we embarked on a delightful walk along Cienfuegos’ shore, which had an amazing collection of wood villas fully restored and painted in bright colors.

Colorful wood houses in Cienfuegos

Day 9. Friday, December 9th, 2018. Large windows, stone roads, and burning fields.

Trinidad was memorable since minute one, when enjoying a splendid breakfast in our hotel restaurant (a restored colonial mansion) we encountered a huge Tiffany-like lamp shaped like a pineapple. Some of us (David C. and Liliana, especially) found this glass fruit fascinating and hypnotizing especially because of its gravity-defying size. After getting over our infatuation with the piña lamp, we went out for our morning exploration of this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Trinidad is a breathtaking 500-year-old city, impeccably preserved. We started our walk up a narrow stone street with colonial houses on each side. Amative of domestic architecture I must say that the magnitude of the windows, its beautiful latticework, and the contrasting bright colors of the walls pushed me to the edge of hyperkulturemia. I tried to snap as many pictures of windows and doors as possible, looking to preserve the beauty of that day in a more tangible medium than my memory.

Incredible pineapple-shaped lamp

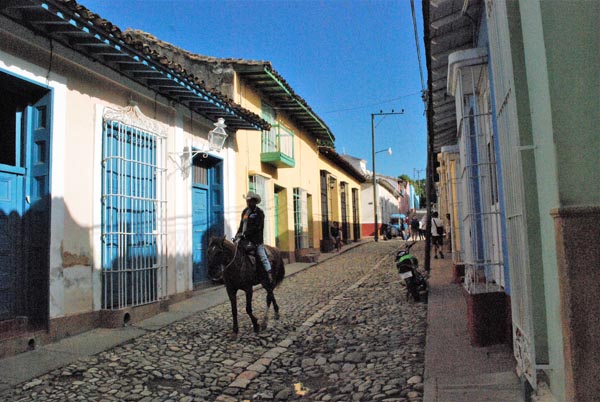

Beautiful street in Trinidad

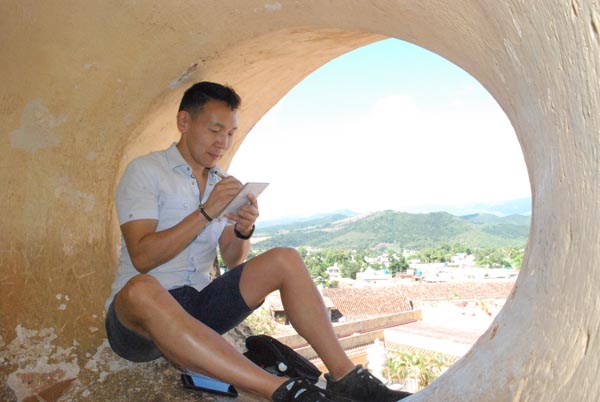

Up the street, the main square, church, government house, and museum were waiting for us, equally splendid. On a particularly hot day we took comfort first on the church’s breezy porch and later exploring the Casa Iznaga, an 18th-century house today repurposed as a colonial architecture museum, where some of us took advantage of the airy patio to recharge energy. Later we walked to the Cantero residence, a 19th-century opulent mansion with an ample patio and a spectacularly high belvedere where all of Trinidad could be seen and photographed (or sketched if you were Paul or Dan). The breathtaking views from the top of the Cantero home resemble a patchwork of orange roofs and green treetops. Before departing from Trinidad, we visited the San Francisco de Asis Convent, today a museum of the revolution, with displays of tanks, cars, and a large number of framed images of Fidel, Che, and other revolutionary heroes. Being the architecture lovers that we are, we didn’t spend much time looking at the exhibition and decided to invest the remaining period (and energies) climbing yet another bell tower for yet another fabulous views of the city.

Belvedere in the Cantero residence

View from the Cantero Residence

Convent Bell tower

Dan sketching inside the convent bell tower

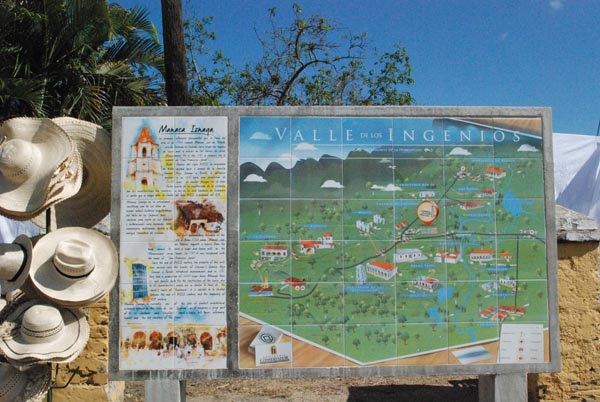

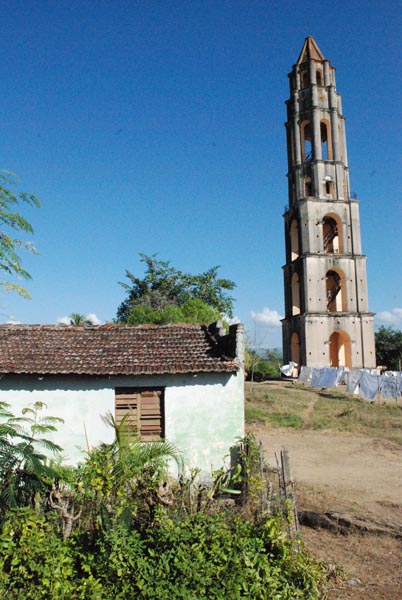

On our way to Camaguey, Monty gifted us with a stop at Manaca Iznaga, a Mirador overlooking an 18th-century sugar plantation called El Valle de Los Ingenios. This Mirador, located at the top of a hill, allowed us to appreciate the landscape, an immense extension of fertile land previously used as sugar plantations—the moment we visited this site many of the hilltops were burning, adding a dramatic effect to the landscape. Next, we had lunch in a fully restored manor house surrounded by spectacular greenery, a watchtower, smaller houses, which seem to have belonged to slaves in previous times, and a fully functioning train. I believe that this very well-maintained sugar plantation with its adjacent service structures would be a magnificent place to document thoroughly.

Victoria enjoying the sugar plantations view

Steve and Liliana chillin' in a beautiful manor

Day 10. Friday, December 10th, 2018. Bicycle rides and defiant citizens.

Camaguey is the third largest city in Cuba, characterized by very high temperatures and an impetuous sun. Also, Camaguey doesn’t follow the Leyes de Indias town layout. Instead, it has a maze-like configuration with blind alleys, forked streets, and different sizes of plazas. Another interesting fact about Camaguey, which places it on my top-three favorite places in Cuba, is its picturesque bicitaxi landscape. Bicitaxis drivers park neatly on the side of buildings and constantly move to the rhythm of sun and shadows creating a beautiful choreography of wired frames and colorful canopies.

Like many things that are highly valued and praised in Cuba for their aesthetic qualities, bicitaxis are not exempt from controversy, at least in my own internal and deeply personal debate. These human-powered touristic vehicles, which I feel so guilty to have enjoyed so much, are like many other means of earning a scarce living in Cuba: highly oppressive and physically demanding. In Camaguey, unlike other provinces in Cuba, it didn’t take much effort to get people talking, or ranting, about life in this enigmatic island. When I enquired about his peculiar bike seat, our bicitaxi driver bitterly expressed that after being diagnosed with manifold medical conditions resulting from his long pedaling on an uncomfortable bike seat, he decided to engineer his own. “It’s not pretty, I know, and I ignore the mockery of my fellows because what’s really important to me is to continue working and providing for my family.” By no means I thought his seat was ugly. On the contrary, I found it ingenious and a true testament to human adaptability and resourcefulness. I shared my opinions with him, he thanked me for my observations and promised to send me pictures once he had improved it. Sadly, I doubt that I’ll ever receive news from him (or any of the other people I asked to contact me) given that one hour of internet costs approximately 5% of an average Cuban salary. When I asked if he gets rides every day he laughed at my naiveté. “I wish,” he responded and later explained that regardless of his monthly rides he must pay a standard registration fee to the government for his bike. I bitterly thought, as I have many times before on this trip, that it’s almost impossible to visit Cuba and avoid supporting the revolutionary government.

Bicitaxis resting in the shade in Camaguey

Our bicitaxi driver (on the right) discussing his creation with a colleague

Steve and Liliana enjoying our day in Camaguey

In between rides with my forthcoming motorist, I got to experience the Colonial city slowly as his words and facial expressions rumbled in my head. On the Plaza San Juan de Dios stop, Paul and I stepped in a scenic pulperia driven by our shared curiosity of what kind of staples one can acquire in Cuba. In my case, this curiosity is founded in the appalling food crisis that has taken over Venezuela in the last decade. Unprecedently, in what not long ago was a very wealthy country, supermarkets’ and convenience stores’ shelves are empty except for non-basic foods like soy sauce, ketchup, mustard, spices, Cheetos, etc. Finding basic food provisions in Venezuela is an insurmountable task, and I’ve always been interested to see how the situation compares to Cuba. So far, or at least in this pulperia, Cuba was doing much better than Venezuela with a shelf replete of two products extinct in Venezuela: rice and oil.

The tall and jolly owner greeted us and patiently answered our questions: yes, pulperia is an outdated word for a convenience store and not a place where they sell octopuses (pulpos in Spanish), the rice came from Thailand, the store belonged to his grandfather. When he picked up on my accent, the interrogation switched. Yes, I’m from Venezuela. No, I haven’t been living there for over 10 years. Yes, I love Canada. It is a great country and yes, I identify myself as a strong oppositionist to the current Venezuelan regime. His smile faded, and his eyes filled with sadness, how can you tolerate that man? He shouted, without mentioning his name I knew he was talking about Venezuela’s current “president” Nicolas Maduro. Surprised by an unprecedented political outspokenness and an astonishing knowledge of current Venezuelan politics, I stayed inside the store wanting to hear more. We chatted about Venezuela’s lost opportunities for liberation and about his estranged wife who left for the Cuban doctors’ exchange program and never came back with his daughter. “These governments are tearing families apart,” he said at the end. I apologized for having to leave our conversation. I was really sorry to leave, but it was time to move on to our next stop. While walking back to the bike, I thought about Cuban doctors all over Venezuela and how their lives were being affected by all the political impositions. In my opinion, without losing sight of its beautiful Colonial architecture, Camaguey stroke me the most as a strong, resilient, brave town.

We left Camaguey and, as Monty described it, we entered uncharted territory. We were about to drive and stop in small rural towns where tourists don’t usually go. But we were no regular tourists, we were architecture devotees, with a knowledgeable leader and a very audacious bus driver, willing to go anywhere for a remarkable building. We drove along hundreds of kilometers of tall, green sugar plantations that, Monty explained, were ready to harvest once the fluffy white flower had appeared on top. On our many bus rides, we also learned about all the infrastructure necessary to process sugar canes into sugar, and how proximity and speed were key to avoid inopportune crystallization in sugar canes. The architectural response to these processes is evidenced everywhere around Cuba in manors, fields, trains, slave housing, and mills. On our next stop, we benefited from visiting what in the 20th century had been the fourth most important sugar mill in Cuba: La Central Argelia Libre de Manati. In this sugar town, we visited a 1930’s theatre and passed by a sleek modernist school, both still functioning. After buying some fried corn snacks for the road, we boarded the bus and dove to Gibara, our next stop. We arrived at Gibara late in the afternoon after the sun had set. The town was very dark, but still we were able to make sense of the small scale of the place, which was inundated by the sound and smell of the sea.

Our hotel was a big, reformed, well illuminated colonial house, which contrasted with the town’s washed out façades and humble, narrow streets. Some of us had dinner at the only available restaurant in Gibara, or at least the only one offered to us. Also inside a colonial house, the restaurant was an extension of the hotel a couple of blocks away by the seashore. It had the same Iberostar finishes and furniture, the same polite treatment for tourists, and even some of the same employees would walk us back and forth.

Day 11.

The next day, following Monti’s advice we woke up early to walk around our host town to explore it before we left. It was worth it. Gibara’s architecture is homogeneous, comprised of different types of modest colonial houses with ranging levels of preservation. What made Gibara special for me were three things: first, a collection of colorful Spanish mosaics spread around the town’s façades and some interiors, these tiles reservedly reference a more affluent past; second, the ubiquitous presence of the sea through its smell, sound or view; and lastly, an authentic cigar factory right in front of the main square. Once we encountered it by chance on our explorative walk, we were captivated by it and didn’t move until it was time for us to leave town. The gate of the factory was guarded, and we were denied access, but the sentinel didn’t have a problem with us peeping through the windows and observing the process. Luckily, we were greeted by a charming, chatty, and very friendly worker sitting by the window. He patiently explained to us the phases of production of cigar making and even posed for the pictures. He answered our questions while working under the rhythm of Juan Gabriel, a popular and beloved Mexican singer to which most of the employees were humming after. The architecture of high ceilings and large windows allowed the working space to be fresh and naturally lit. However, working conditions were deteriorated by the precariously lit working stations—I know it’s contradictory, but for such fine work additional light is needed—and very basic, uncomfortable seats. For some reason, oppressive work seems less so inside a repurposed colonial house under the Caribbean sun. Fortunately, we were reminded of it by our worker-friend, who told us they made approximately 15 CUC a month and they were supposed to produce about 200 cigars a day. One cigar may range in price between 5 to 15 CUC; you do the math.

View from our Hotel in Gibara

Gibara's beautiful tiles

Cigar factory

Our "guide" inside the cigar factory

On our walk back to the bus and five minutes to spare, I was spontaneously invited inside the house next to our hotel. When I say “spontaneously invited,” I must reveal my method. I stand in front of the doors of the houses (sometimes even uttering a melodic Buenas!) with a wide smile. Once someone looks at my eager eyes and listens to the reasons behind my standing there—I’m an architect and would love to see your house—they say “sure, come on in.” The inside of the colonial house was well adapted to “modern” living with a new kitchen and bathroom. The central patio afforded all the surrounding spaces illumination and ventilation. The well-preserved furniture was scarce but neatly distributed around the social spaces, which were impeccably clean. That generous invitation to one of Gibara’s homes evidenced how people in smaller cities outside of Havana have access to better living conditions and larger spaces.

A beautifully preserved colonial house where I was "invited" in

On our way to Santiago de Cuba, we visited Holguin, a prosperous city characterized by colonial, neoclassical and eclectic architecture. Holguin is Cuba’s fourth largest city and a popular destination for tourists (mostly Canadian) due to its airport, which serves the region’s nearby beach resorts. Holguin houses one of Cuba’s two Canadian Consulates and is the home of the Bucanero and Cristal brewery (also in conjunction with Labatt, a…wait for it…Canadian brewery. Surprised?). All these economic activities translate into a vibrant city with a substantial number of well-preserved buildings and lively commercial streets.

On one of the sides of Calixto Garcia’s Park is the 1939 Teatro Eddy Sunol, a gorgeous theatre that, even after receiving an unfortunate paint job, stands proudly symbolizing Holguin’s culture. This Art Deco treat is the home of Holguin’s symphonic orchestra and a vivacious cultural heart for the city. Another outstanding building devoted to cultural and artistic expression is the Centro de Arte y la Cultura de Holguin; originally called La Casa de las Moyuas, it was commissioned in 1845 by a wealthy doctor and his family to live in. This large colonial house has had many lives as a family home, hospital, police station, movie theatre, hotel, and retail store, until the year 2000 when it was finally revamped as an art gallery and school. Inside this artistic hub, music and color are everywhere; many of us (especially David C., who didn’t want to leave) acquired prints and paintings, enjoyed a coffee, and quietly observed a couple rehearsing for a play in the spacious patio.

Holguin

Teatro Eddy Sunol in Holguin

Casa de las artes y la cultura Holguin

After leaving Holguin, we stopped for lunch and a tour of Bayamo where we visited the charming Catedral del Santísima Salvador, which dates back to the 16th century, and the Carlos Manuel de Céspedes home. Right outside of Bayamo, Juanito, our heroic driver, took us through a very intricate unpaved road to see an outstanding building, the scientific forestry research station built in 1968 by Walter Betancourt. The brick and traditional roof tile building is a superb structure, standing in perfect harmony with its natural surroundings. Because it is an active government building with research activities happening inside the premises, we were denied access and were only permitted to photograph it from the exterior. Nevertheless, the magistral use of traditional materials and the richness of the forms made this trip worthwhile. Later that evening we entered the energetic Santiago de Cuba, our home for the next two days.

Catedral del Santísima Salvador Bayamo

Santiago is Cuba’s second largest city and an amazingly dynamic urban municipality, even today. I’ve heard of Santiago, but I wasn’t prepared for what it had to offer. I can say now that it was one of the trip’s most pleasant discoveries. Our hotel was located at the beginning of a busy commercial street called Jose A. Saco, with brightly colored façades, lots of lights, a handful of restaurants, and well-supplied stores with wide window displays. Naturally, seduced by this explosion of color, light, and people, I went walking up this street where I found Lazaro, our local tour guide, thrilled about a newly open Reebok store, taking pictures to send to his wife back in Havana. He kindly rejected my invitation to walk around, because he wanted to check out another Puma store nearby and see what else the Saco street had to offer commercially. Deep inside I knew this flagship, a pedestrian street with rich displays of wealth, was deliberately staged for tourists. Don’t get me wrong, everyone is welcome to walk on these streets, but its prohibitive prices discriminate regular Cubans from lingering too long. As an experiment to keep some spatial and social perspective, I decided to return to the hotel from a parallel street. I wasn’t wrong. The Jose A. Saco street was not the rule in Santiago but the exception. I didn’t expect to find contrast in such proximity, but I wasn’t surprised. Spatial inequality in Cuba is complexly ubiquitous. Both extremes are usually intertwined; the richly ornamented, carefully staged tourist areas share walls and passageways with Cubans’ neglected, dark, everyday spaces. On the street I used to return to my starting point, there were no Reebok stores. It was pitch dark, the sidewalks were narrow and full of people waiting for the bus or off standing in queue waiting for bread distribution. This street’s only relationship to its rich twin was through a courtyard where a group of people was doing tai-chi with an open gate on one side and a closed one on the other. Dare to guess which one was which?

View of the Jose A. Saco street from our hotel

Parque de Ajedrez by Walter Betancourt

Day 12. December 12, 2018. Santiago de Cuba

On our first full day in Santiago we had two outstanding local guests/guides: from the town’s historian office, the chief archaeologist for the city, and the head of the city planning office, Gisela Mayo. Our city visit began in Parque Cespedes, Santiago’s main square. Around it, respecting the Leyes de Indias were the Santa Ifigenia Cathedral, the Palace of the Municipal Government, and the Diego Velazquez’s house, originally the Governor’s residency. Fortunately, we visited the interior of the Museum Casa Velazquez, the oldest house in Cuba, which dates back to 1516. The exquisitely kept home is divided in two main bodies, the original Spanish structure built in the 16th century with heavy stone and brick arches and columns, and the new 19th-century Creole addition with slender wood columns and beams to resist earthquakes common in Santiago. But the differences between the two parts of the house go further. In the oldest portion of the house the exterior windows were heavily protected by mahogany wood lattice-work to keep indiscreet gazes away from the respectable ladies of the house. The patio was used for water recollection and storage and as ventilation for a nearby oversized furnace. On the newest (19th century) portion of the home, the windows were covered by slim metal bars, allowing in large amounts of light, air, and visual contact. The second patio became a social place, especially for the ladies of the house who would paint, sew, take lessons, and eventually entertain on this open area. An additional coach room was added, and the furniture selected was lighter, made of wicker and slimmer pieces of wood. On the original house, the furniture was heavy, solid, and made of hardwood.

Palace of the Municipal Government Santiago de Cuba

Interior view of the 16th century portion of the Velazquez house

"Old" living room inside the Velazquez house

Second (19th century) patio inside the Velazquez house

"New" living room inside the Velazquez house

After the Velazquez house, we boarded to the bus for an overlook of the city guided by Gisela, who explained to us that special emphasis had been given to conserving the historic district but also connecting it with other important areas of the city to create a well-articulated metropolis. We drove along spacious avenues, passed by the spectacular Mariana Grajales square, explored residential neighborhoods, and finally stopped in the famous Cuartel Moncada. The imposing military structure dates back to the 19th century, but after a demolishing fire destroyed the original building, it was rebuilt in 1930 with an Art Deco style. The well-known July 26th, 1953 attacks which sparked the Cuban revolution left three important traces in the building. First, the bullet holes have been purposely left in the west side of the main façade as a reminder of the first rebellious attempt.

The second reminder is the large, red number “26” on top of the main entrance, commemorating the day when 135 men led by Fidel Castro attacked the barracks. The last and definite architectural trace comes in the form of the building’s current programs a museum of the Revolution and a public school. I was surprised to visit this military structure, so representative of the Cuban revolution and to find such obvious similarities with Venezuela’s “Cuartel de la Montana,” the military academy built in 1910 in Caracas and where Hugo Chavez’s remains are. In Venezuela, the Cuartel de la Montana, originally white, is now painted with yellow, white, and red, very similar to the Cuartel Moncada. Also, a large, red “4F” was built on top of the entrance of el Cuartel de la Montana, remembering Chavez’s first failed attempt against the government of Carlos Andres Perez on February 4th, 1992. The similarities between the military structures are far reaching and merely esthetic, which in my perspective represents a clear analogy of Venezuela and Cuba’s alliance: superficial and desultory.

Bullet holes in the Cuartel Moncada

Cuartel Moncada Santiago de Cuba

Cuartel de la Montana next to Cuartel Moncada. Image credits: Radio Rebelde and Cuba Holidays

After a long visit to the military museum inside the Moncada barrack, we drove by the opulent neighborhood Vista Alegre, home to Santiago’s 20th-century large fortunes like Bacardi and Bosch and ironically the area where Raul Castro stays today when visiting the city. We had lunch near El Castillo de San Pedro del Morro and briefly visited the 17th-century impressive fortress. Afterward we went to see the outstanding Universidad de Oriente medical school, built in 1964 by the Colombian architect Rodrigo Tascon. The faculty of Medicine layout develops around a main uncovered courtyard with greenery and vegetation that keep the interior spaces fresh and illuminated. The most appealing characteristic of the building is its roof, a structure comprised of a series of concrete inverted pyramidal hyperbolic paraboloids.

Faculty of Medicine interior view

Faculty of medicine cafeteria

Before moving on to our next and last stop in Santiago, I would like to invert the order of the tour for the reason that I would like to close this blog entry with my reflections about the Santa Ifigenia Cemetery.

On our last day in Cuba we visited the city of Guantánamo. It had nothing to do with the Guantánamo Bay military prison except for a glance from the mirador we stopped to eat at. In Guantanamo we drove by the Plaza de la Revolucion, and we discovered a charming modernist church and walked around the small town. We also visited the house of architect José Lecticio Salcines Morlote, built in 1919.

Detail of cross in Guantanamo's modernist church

Interior of Guantanamo's church

Modernist church in Guantanamo

José Lecticio Salcines Morlote built in 1919.

Back to Santiago de Cuba, as I stated before, I end this blog post with our visit to the Saint Ifigenia cemetery, a place where I want to come back. The Cemetery is an extensive, beautifully landscaped resting place where many illustrious Cubans lay today. The history of the country can be reconstructed by walking this extended plot of land and carefully examining the tombs and mausoleums. The most important occupants of this piece of Santiago are Jose Marti and Fidel Castro. The Jose Marti Mausoleum was designed by Jaime Benavent with sculptor Mario Santi. This breathtaking, 26-meters-high structure was completed in Jaimanitas’ stone and top quality white marble. The Art Deco mausoleum is replete of significance including the sun always shining on Marti’s tomb through a carefully designed skylight and six caryatids representing the first six provinces of Cuba (Camaguey, Havana, Las Villas, Matanzas, Oriente, and Pinar del Rio). This outstanding mausoleum is a work of art and engineering with the ability, essential to any piece of architecture, to move you almost to tears while inside. However, I was equally impressed by a much less monumental tomb: Fidel Castro’s grave. Castro’s tomb is comprised by a grey boulder significantly brought from La Sierra Maestra featuring a small plaque that reads Fidel. This puzzling act of humility certainly adds another layer of complexity to the highly controversial character that Fidel Castro was.

Jose Marti's mausoleum. Image courtesy of Victoria Young.

Jose Marti's sculpture made of white marble. Image courtesy of Victoria Young.

Fidel's tomb. Simple in contrast with its surroundings. Image courtesy of Victoria Young.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top