-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

In Search of Chinese Architecture

Society of Architectural Historians China Field Seminar Report

December 27, 2017–January 7, 2018

Day 1, December 27, 2017, Shanghai, mildly cold but sunny

It’s the first day of the tour. We are in Shanghai for the China Field Seminar of the Society of Architectural Historians.

The itinerary is intense; it will take us to a wide range of buildings, from the Han tombs from over 2000 years ago, to the Shanghai World Financial Center completed in 2008, and just about everything in between: classical gardens, private houses, religious edifices and vernacular buildings, in Shanghai, Suzhou, Zhenjiang, Nanjing, Yangzhou, Hangzhou, Guiyang and Guangzhou in 10 short days. To me this trip is an effort to find an answer to one overarching question: What is Chinese architecture today? Or to put it slightly differently: What do we mean when we speak of “Chinese architecture” in the twenty-first century? The answer may be significantly different for different people: for architectural historians, for architects, and for those who share with us an interest in Chinese architecture, particularly given China’s role in contemporary global affairs. My goal is not to locate a universal definition of Chinese architecture, which might not be possible in any case, but rather, to treat the unique experience of this field seminar as an exercise in critical thinking and reflection. And I sincerely hope and urge my friends in the group to share their thoughts. A big thank-you in advance.

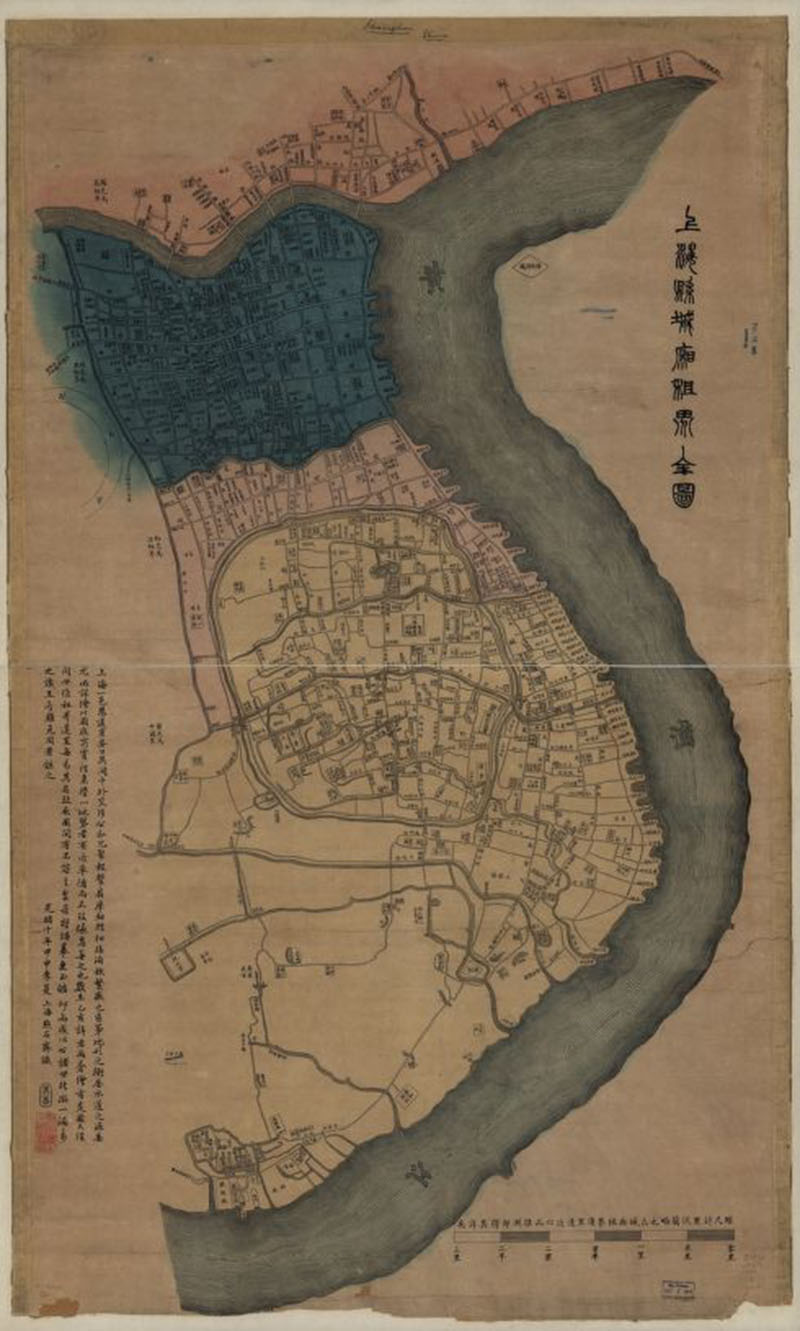

A quick rundown of the historical circumstances that triggered tremendous change in China in the last 150 years. The last imperial dynasty, the Manchu Qing court (1644–1911), was forced to open treaty ports for commerce, Shanghai among them, after a series of armed and failed conflicts with Western powers (the First and Second Opium War of the mid-nineteenth century were among the most traumatizing for China). The Qing dynasty fell after the revolution of 1911, whereby the Republic of China was founded the next year with Sun Yat-sen installed as its first president. Instability was worsened by continuous conflicts among political cliques, the rise of the communist party in the 1920s, increased Western dominance in virtually every aspect of social and cultural life in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century China, and the invading Japanese troops from the early 1930s to the end of WWII. The power struggle between the Nationalist and Communist parties which led to years of bloody civil war and the founding of the PRC in 1949, was followed by the ideological warfare waged by the Communist party under Mao Zedong which culminated in the Cultural Revolution that started in 1966 and lasted 10 long years, wreaking cultural havoc.

We are staying at the Astor House hotel, an architectural curiosity itself. Originally the Richards Hotel, it was built in 1846 to be the first Western hotel in Shanghai and China. Over the decades, the location, name and style of the building have been changed, renovated or restored many times, with its current Neo-Classical/ Baroque style elaborately worked out in 1907. The hotel does not shy away from showcasing its glory in housing celebrities including Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin, George Bernard Shaw and many others whose likenesses are displayed throughout the hotel.

[Figs 1 & 2, pictures of the interior of the Astor House hotel]

A few of us couldn’t wait until the next day to walk on the Bund as scheduled in the program, so we started right after our dinner tonight. The lights were amazing. Shanghai is certainly a city that is very self-conscious about presenting its image to the world.

[Figs 3 & 4, pictures of lights across the river from the Bund, and on the Bund]

Day 2, December 28, 2017, Shanghai, drizzling all day

Busy day today. In the morning Professor Lu Yongyi (卢永毅) of Tongji University, which boasts one of the best architecture programs in China with about 2700 full-time students in its College of Architecture and Urban Planning alone in 2016, joined us for a walking tour along the Bund. Professor Lu started with a brief history of modern Shanghai. The Treaty of Nanking that ended the first Opium War in 1842, forced the imperial Qing government to open treaty ports along the seaboard, including Guangzhou (Canton), Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo and Shanghai. This allowed the British to set up their consulate and granted their merchants residence in the city. The competing colonial powers effectively turned Shanghai into three different municipalities: the International Settlement (a conglomeration of the British, American and other settlements in Shanghai), the French Concession, and the walled Chinese city by the end of the nineteenth century. Construction and spatial organization of the landscape of the city, especially along the Bund, was ad-hoc and competitive as different interests fought for spatial and stylistic representation and domination.

[Figs 5–7, map of Shanghai and photos of the Bund during the late-nineteenth century and 1930s]

After the brief introduction to the city’s development from an inconspicuous fishing village to its rapid rise to the international stage in less than a century, we had a taste of the architecture along the Bund, a sort of “appreciating the flowers from the back of a racing horse,” as the Chinese idiom would have it [zou ma guan hua,走马观花], given our limited time frame.

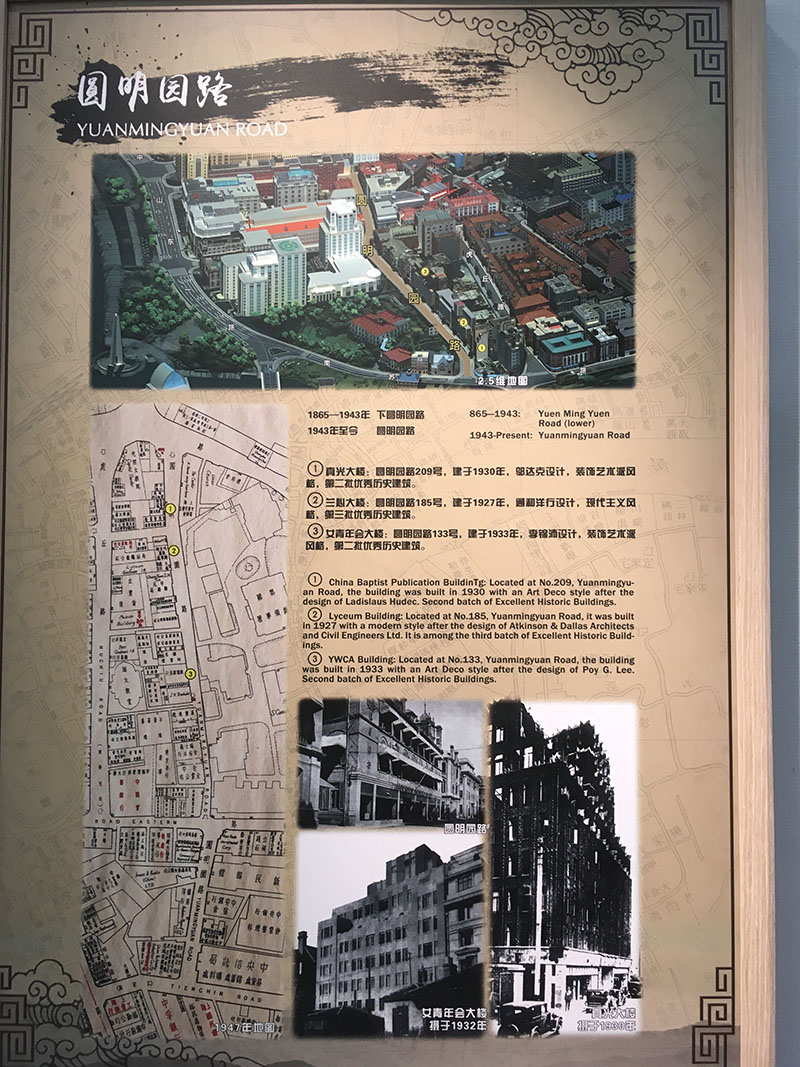

We started from Yuanmingyuan Road, just behind the waterfront structures on the Bund, and worked our way to the waterfront. Western style buildings dominated this street, just like those along the Bund. Many structures, however, are not open to tourists and their original purpose has been changed. The gorgeous Art Deco China Baptist Publication Building, for example, designed by the prolific Hungarian architect Laszlo Hudec in 1930, is now used as an office building. Mostly made up of religious, educational, cultural, and recreational institutions, the architectural identity of Yuanmingyuan Road corresponded to its location behind the waterfront. The waterfront itself is dominated by more explicit expressions of power and prestige: banks, customs house, and luxury hotels, that facilitated imperialist endeavors in late nineteenth-century Shanghai.

[Figs 8–10, pics of buildings on Yuanmingyuan Road and the Bund]

When the majority of these buildings were built in the first three decades of the twentieth century, Chinese architectural historians and architects grappled with the question I proposed at the beginning of this blog; what is Chinese architecture? And some of them responded very differently from how we might today. Liang Sicheng (1901–1972), the eminent architectural historian and architect understood this architecture of modern China as a reflective of a colonized mentality. In a talk he gave in 1950, he noted: “For over a century, the Chinese have completely lost their confidence. A completely colonized psyche considers everything and anything foreign superior. ... This shameful history of 109 years is shown nowhere more explicitly than in her architecture.”1 Seventy years later, how have our views towards these buildings changed?

[Figs 11&12, pics of Bund with Santa both inside and outside]

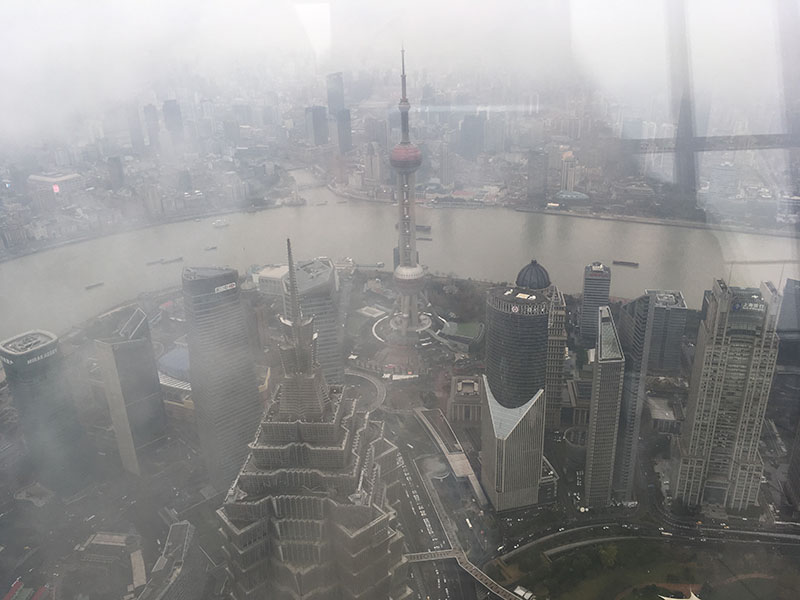

A short ferry-boat ride across the Huangpu River took us to the Shanghai World Financial Center, the 492-meter skyscraper, for its famous observation deck on the 100th floor. Rain and clouds made it hard to see much, but the observation tower still offered occasional panoramic views of the city.

[Figs 13 & 14, views from the 100th floor]

The afternoon was taken up by the Jewish Refugee Museum and the Shanghai Museum. During WWII more than 20,000 Jews came to the city to seek refuge from the purges in Europe. The former synagogue, now the main structure of the museum, is a three-story brick building that was originally a private house. On the upper floor was an exhibition on Anne Frank. A quick walk to the Shanghai Ark afterwards, so called because of the refuge the city provided to the Jews during this time, concluded our visit to this part of the city, and we were on our way to the Shanghai Museum.

[Figs 15 & 16, Jewish Refugee Museum]

A few of us opted to visit the nearby Shanghai Planning Exhibition Center instead. The gigantic model of the city that almost took up the whole third floor was mind-boggling, and there were exhibitions of both long-term development plans for the city, and temporary art exhibitions related to urban development in contemporary China. The current exhibit examines the relation between urban and rural development.

[Fig 17, picture of the city model]

On the upper floor I was delighted to find an exhibition of old streets in Shanghai, which juxtapose segments of old print maps, period photos, and 2.5-dimensional maps (See what a 2.5-dimensional map is in the picture below), to locate the buildings in the cityscape. It was very nicely done. One gets a good sense of not only the form ands style of the buildings, but also their spatial relation in the larger cityscape. And here’s Yuanmingyuan Road we saw earlier today!

[Fig 18, Yuanmingyuan Road in exhibit]

Day 3, December 29, Shanghai to Suzhou, overcast

Left Shanghai bright and early today. We made good time and headed straight to Zhujiajiao, about an hour drive west of Shanghai. Zhujiajiao is called a water town: the canals are its lifeblood, offering means of transportation before automobiles, and now they provide tourists a soothing tranquility not found in the concrete jungle of the city.

[Figs 19 & 20, pictures of Zhujiajiao]

Off the well-trodden track of tourism, I noticed an alleyway that seemed very calm in comparison, probably because it was not open to the public. A guard was stationed at the entrance of the alley, but he didn’t stop me. I kept walking past ordinary houses along the alleyway, until I couldn’t go any farther. At the end of the alley was a stately entrance structure announcing its non-ordinariness and a guard who informed me that it was a private residential area. It was a secluded luxury apartment complex tucked away at the deeps of the alley on the river.

[Figs 21 & 22, pictures of luxury apartment complex at Zhujiajiao]

Although the locals and perhaps also your tour guides could proudly tell you that the town boasts a history of over 1700 years, much of what is presented to the visitors today seems newly restored or rebuilt.

[Fig 23, picture of pavilion with peeling paint and cracks]

We continued to the Suzhou Museum designed by I.M. Pei that opened in 2006. I had never been there before, and remembered being unsure about the photos of the museum exterior when I first saw them. But the entrance hall, which greeted visitors with Pei’s take on classical Chinese painting and garden design across the reflecting pool beyond the glass window, made my uncertainties disappear.

[Fig 24, picture of view from the main hall; rockeries on white walls. Pei’s post-modern take on classical painting and garden design of China]

The exhibition spaces work well: clean and simple lines and shapes with a subdued color scheme and indirect natural light work together to highlight the artworks on display. The effectiveness of the exhibition is enhanced by the modest scale of the galleries. What is most impressive is the intricate and fine craftsmanship throughout the museum.

[Figs 25-27, gallery spaces of Suzhou Museum]

Afterwards we walked through the adjacent Zhongwang Palace of the Taiping Rebellion leader Li Xiucheng (1823–1864), a part of the Suzhou Museum complex, over to the Humble Administrator’s Garden(Zhuozheng yuan, 拙政园)next door. These places are right next to each other, because both the museum and the palace were part of the garden at one point. Covering 12.5 acres of ground, it is the largest extant classical garden in Suzhou. The garden was originally constructed in the early 16th century, but its ownership has changed hands many times. Its current layout of three different parts: the eastern part intended as an agricultural and horticultural space for producing vegetables, fruits, and flowers that was completely rebuilt in 1959–1960, the central part, and the western section which was known as the Supplementary Garden, was established in the last fifty years or so.

Buildings play an important role in the organization of the spaces, in both their abundance and in their variety of types.

interior.jpg?sfvrsn=3cce5f9b_2)

.jpg?sfvrsn=34ce5f9b_2)

.jpg?sfvrsn=38ce5f9b_2)

[Figs. 28-30, different types of buildings in Zhuozhengyuan: a tang, a lou, and a ting]

Even buildings that are outside the garden boundary are included in the view, becoming part of the experience.

[Fig. 31, borrowed view of the Beisi Pagoda]

Such a classical garden evokes a full-spectrum sensorial experience: sound of the rain, fragrance of the lotus, views from near and far, literary and philosophical references, and more importantly, the spatial experience of moving through the landscape with its undulating terrain. Spaces are layered by means of blocking, framing, allusion, expansion and contraction, unfolding with every step of one’s movement as if in a Chinese landscape painting. The constant change of vistas is, in fact, meant to evoke the experience of nature outside human habitation.

We then boarded the bus for Xuanmiao guan, only to find that the Daoist Monastery was closed by the time we got there. A quick walk around the grounds was all we could do. Professor Steinhardt gave a wonderful lecture on Chinese architecture at dinner time tonight. She talked about the recognizable features that make Chinese architecture “Chinese,” the foreign influences on Chinese architecture throughout its history, particularly from India and under the Mongols, and the modular and standardized production of architectural components in Chinese construction.

Day 4, December 30, 2017, Suzhou to Zhenjiang to Nanjing, sporadic drizzling and fog

We walked out of our cute old-house-turned-hotel after breakfast, a curious matter of a paper-white-bread sandwich with egg, milk and coffee brought to the room, to the nearby Twin Pagodas, after a pleasant stroll on the canal leading us to the Luohan Yuan (Arhat Monastery). Originally built in the late 10th century, the Twin Pagodas date back to the same period, although restorations have been carried out numerous times, the most recent one being about five years ago. Professor Steinhardt explained the early layout of Buddhist monasteries. Unlike what we usually see with later Buddhist monasteries where the main hall is the most significant structure, in earlier monasteries the pagoda, as a symbol of the Buddha and a reliquary of his relics, was as important as the main Buddha hall if not more so. There could be one or two pagodas, or none, at the entrance or next to the main hall. These almost identical octagonal seven-story brick pagodas, a rare case indeed, are important examples of brick multi-story constructions of the early period.

[Figs 32 & 33, pics of pagodas]

What aroused everyone’s curiosity, ensuing much discussion was the remains of the main hall. The five-bay structure, supported by masonry columns, some of which were elaborately carved with floral patterns, has only some columns and column bases left standing. What could have been the shallow incisions on the corner columns? Why were they made of stone?

[Figs 34 & 35, pics of columns of the remains of the main hall]

We then visited the garden of Wangshi Yuan (Garden of the Master of the Fishing Nets) which is tiny compared to the Zhuozhengyuan Garden we visited yesterday, not even one sixth of the latter in size. This exquisite garden is known for its compacted spaces, which so artfully composed as not to feel cramped. Highly condensed views are framed mostly around the central squarish Rosy Clouds Pool. Originating as the famed Hall of Ten-Thousand Volumes and The Fisherman’s Retreat Garden of the Southern-Song retired literatus Shi Zhengzhi, this garden-residence likewise changed many hands until its current form was laid out during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Its western section of the Late Spring Cottage (Dianchun yi) served as a model for the Astor Chinese Garden Court in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York constructed in 1980.

[Figs 36-38, pics of Wangshi yuan]

After a quick climb and then walk around the grounds of the Pagoda of Auspicious Light near Panmen Gate of Suzhou, the oldest pagoda in Suzhou with the original structure dating from the third century BCE, we were taken by a slow bus ride to Zhenjiang, where about 20 minutes were left for us to explore the hill-side nineteenth century complex, started with the British Consulate built in 1890.

[Figs 39 & 40, pics of British town in Zhenjiang]

Day 5, December 31, 2017, Nanjing to Yangzhou and back, sun & fog

Heavy fog set us back two and half hours on our way to Yangzhou this morning. The Fourth Bridge on the Yangtze River outside Nanjing was temporarily closed, and consequently we had to make revisions to our program. We first visited the Ge Garden in Yangzhou, famous for its bamboo plants. Rebuilt in the early 19th century by a Yangzhou salt merchant Huang Zhiyun (1770–1836), the garden was so named because of the visual similarity between the Chinese character ge (个) and bamboo, the owner’s beloved object. Being the symbol of modesty and unyielding integrity, bamboo has been a favorite subject of traditional Chinese painting. Other than the many different kinds of bamboo occupying a sizeable portion of the garden of about 6 acres, a Bamboo Culture Hall displays everything about bamboo, especially in relation to the city of Yangzhou and its literati culture.

What has also garnered tremendous fame for the garden is the so-called Four-Season Rockeries, where architecture, bamboo and rocks of different forms and hues were combined to evoke the different seasonal atmosphere of the year.

[Figs 41 & 42, pics of Ge Garden, bamboo and rockeries]

Two Western Han dynasty tombs were on the itinerary next. The tombs of the first King of Guangling (Yangzhou’s name during the Western Han (202 BCE–8 CE) period), Liu Xu and his queen, for its elaborate burial style called Huangchang ticou, a sumptuous funerary arrangement for the royal members of the Han Dynasty, the highest-ranking tomb style with its layers of protection outside the coffin. Huangchang (literally “yellow intestine”) refers to the cypress wood and its color, after the bark is peeled off. Ti means tops or “heads” of the timbers that all point inward toward the coffin, gathered perpendicular to the coffin’s wall. The tombs were first discovered in 1979 and have been removed from its original site to the current museum location. Among the dozen of Huangchang ticou tombs found in China so far, this burial site of the king and his queen is the biggest, most elaborate in terms of materials used, structure and workmanship, and best preserved of its kind.2

[Figs 43 & 44, Huangchang ticou tombs]

Professor Steinhardt gave us another wonderful lecture after dinner titled “How Chinese Architecture Became Modern.” This is a story of how the first-generation of Chinese architects, particularly Liang Sicheng (1901–1972), Liu Dunzhen (1897–1968), Tong Jun (1900–1983) and Yang Tingbao (1901–1982) helped to transform the Chinese built landscape to its modern form, with the help of education received—with the exception of Liu—at the University of Pennsylvania during the 1920s.

Day 6, January 1, 2018, Nanjing, sunny

Happy New Year!

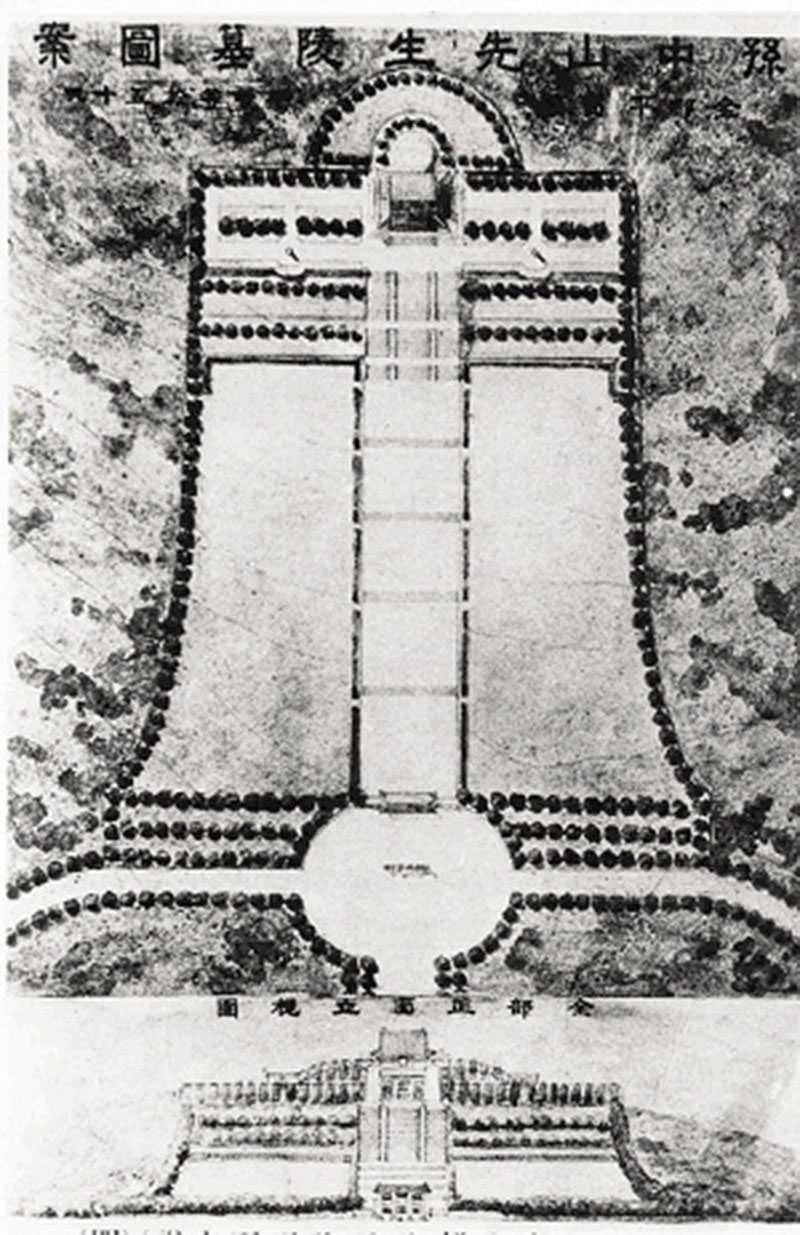

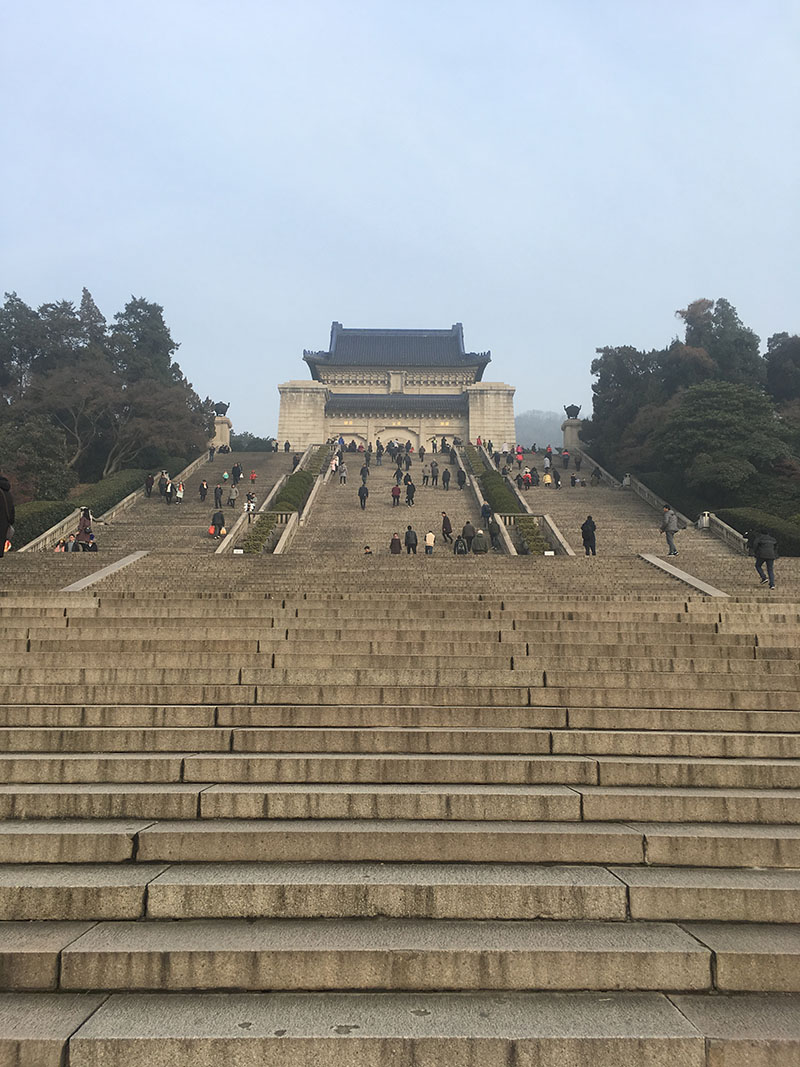

What a day! We started today with Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s mausoleum early in the morning. This complex was designed by Lv Yanzhi (1894–1929), who received his architecture degree from Cornell and won an international competition for the well-publicized project in 1925. The bell-shaped mausoleum complex is approached through a memorial archway, a long walkway through a gate and a pavilion, before culminating at the Sacrificial Hall perched on top of the hillslope of the Purple Mountain. As Delin Lai points out in his study of the mausoleum, the major considerations of the design were twofold: the mausoleum was to be both Chinese and modern, embodying the ideals of the new nation-state of the Republic of China as stipulated by Sun Yat-sen himself. As required by the design competition committee, who wanted a monument “preferably in classical Chinese style with distinctive and monumental features,” the completed mausoleum was a combination of the imperial burial ground in its scale, layout and approach, and Beaux-arts-inspired modern design executed in concrete and metal, materials more permanent than the timber construction typical of the indigenous tradition.3

[Figs 45-47, plan, approach/steps, and Sacrificial Hall of the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum]

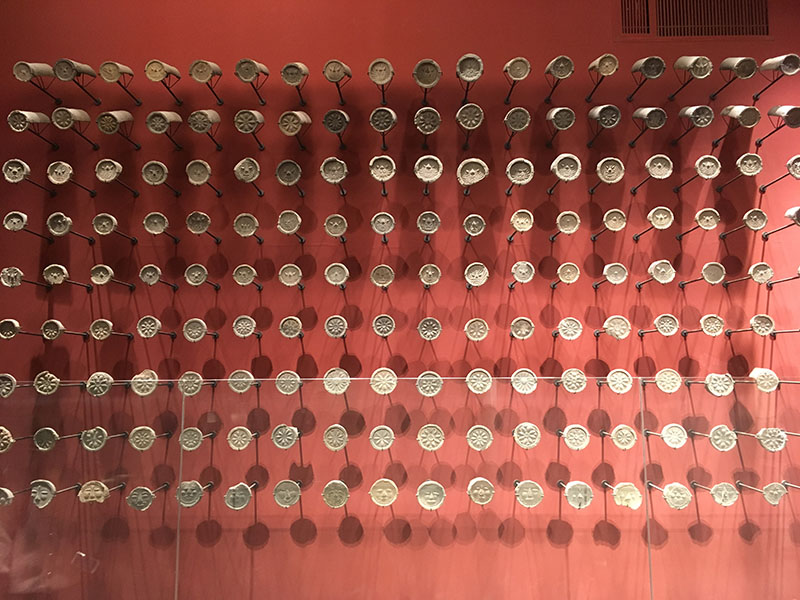

After the impressive Beamless Hall, a hefty brick vault structure without wooden columns or beams built in 1381, the largest among the few extant examples of its kind in China in the Linggu Monastery, and the Xiaoling of the first Ming dynasty (1368–1644) emperor and his empress, we rushed against daylight to visit the Oriental Metropolitan Museum [Liuchao bowuguan/ 六朝博物馆 in Chinese, literally the Six Dynasties Museum]. A 2014 addition to Nanjing’s long list of museums, this modest-sized museum showcases the cultures of the Six Dynasties of China, roughly from the third to the sixth centuries. The lower level exhibits an awesome display of archaeological findings from the old city of Nanjing, the then capital city of the Six Dynasties including ruins of city walls, sewage systems, porcelain and pottery and other cultural relics. The English name of the museum, Oriental Metropolitan rather than the literal translation of the Six Dynasties, indicates the city government’s aspiration to tap into the past glory of the historic city as one of the “Oriental Metropolitan” areas of the world, and Pei Partnership Architects, the designer of the museum, certainly help that aspiration.

[Figs 48 & 49, exhibits in the Metropolitan Museum]

We then went to Nanjing University’s Gulou Campus to see the North Tower designed by Yang Tingbao (also known as T. P. Yang). By the time we got to the Pearl Buck house, however, it was too dark to see much.

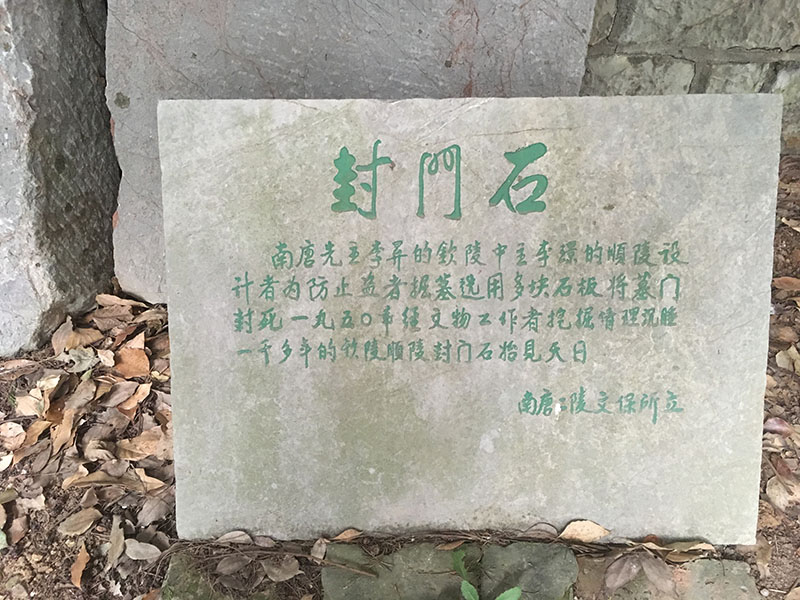

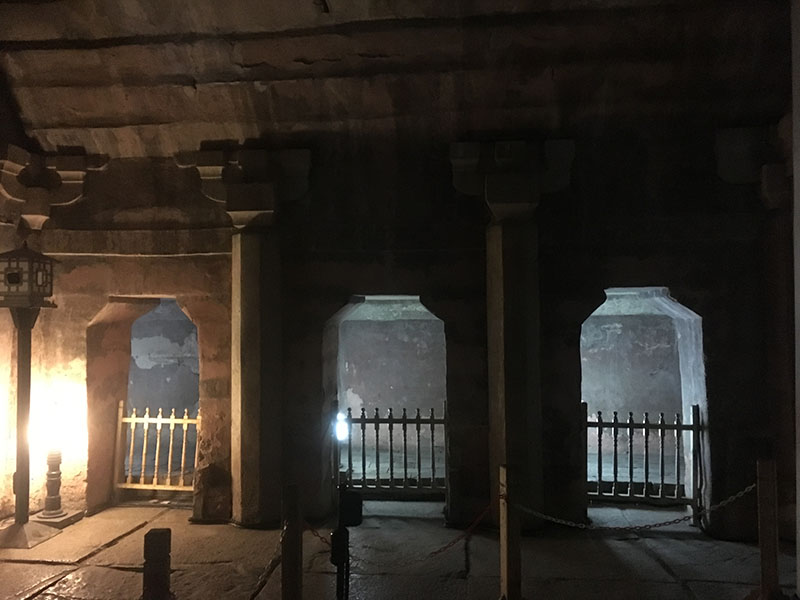

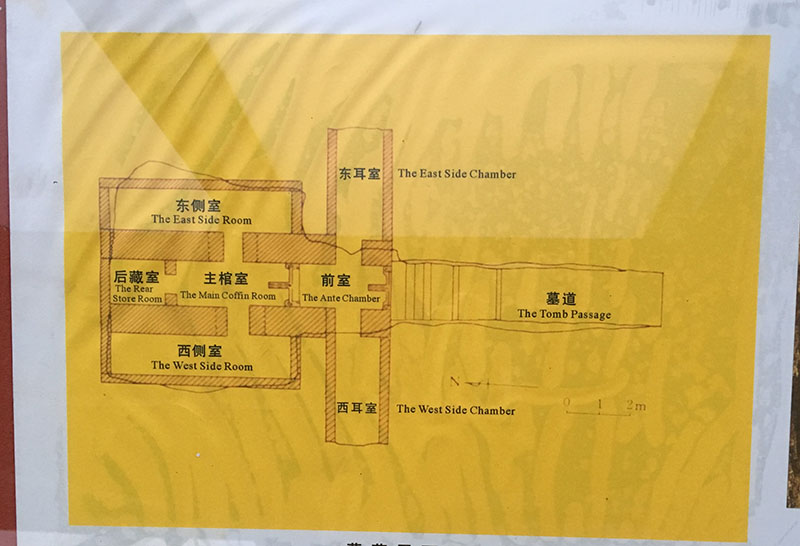

Day 7, January 2, 2018, from Nanjing to Wuhu, cloudy & mild

We got to the Nantang tombs outside Nanjing before the gate was even open this morning. Bravo for the group of troopers for keeping to the schedule! The tombs were for two Nantang kings (r. 937–943, and 943–961 respectively, between the Tang and Song dynasties) that were first excavated from 1950 to 1962. The tombs themselves, especially the first one Qinling, are a valuable depository of information on artistic development in the period concerning architecture, sculpture, painting, and pottery-making. The main chambers of the tombs, although built of stone, show features of timber construction of the period, such as the relief sculpture of the columns and bracket-sets. Sculpture and polychromatic paintings adorn the walls. The exhibition on the excavations, some 600 items in total, including over 200 figurines, is amazing, although the presentation could stand some improvement.

[Figs 50–52, tombs and figurines]

Following this we went to the Porcelain Tower Heritage Park nearby to visit the pagoda that was designed and constructed by a team from Southeast University in Nanjing and opened to the public only two years ago in December 2015. We were in fact joined by a faculty member from Southeast University, Ren Sijie (任思捷), formerly Professor Steinhardt’s student at the University of Pennsylvania, who gave us a nice introduction to the design of the tower and walked the park ground with us. As Chen Wei, one of leaders responsible for the design team from Southeast University, explained, what was started in 2003 as a reconstruction initiative of the long-gone early 15th-century Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, made famous to the European audiences by the Dutch traveller and painter Johan Nieuhof (1618–1672), evolved into a comprehensive project focusing on the protection, preservation and re-presentation of the archaeological complex that was excavated during 2007 and 2012.4 The excavations unearthed valuable Buddhist relics from the original site, including the King Asoka Pagoda and the remains of the Buddha (Shakyamuni) deposited in the underground reliquary. The palimpsest site contained several layers of historical and cultural significance, which has been extensively explored and exhibited in the heritage park/ museum complex through modern technology which at times produces an overwhelming audio and visual overload.

[Fig 53, King Asoka Pagoda, according to the information given in the museum, it is “the largest in volume, the finest in production, and the most complicated in craftsmanship” of its kind discovered so far in China.]

The whole project, reportedly built at the cost of 156 million USD, seems a part of the municipal government’s ambition to capitalize on the historic reputation of the original Bao’en Monastery as the “Greatest Buddhist Monastery” and the city as the “Capital of Buddhism” in China by drawing attention, and tourists, lots of them, to the site and the city.5

It was also interesting to know that the design process involved public feedback in the initial stage. Solicitations were sent out to the public of Nanjing about whether the new pagoda should be built directly on top of the original site of the tower, or at a different location. Final votes determined that the new restored pagoda be built on top of the original site.6 But the design team opted for a lighter structure, a steel-frame skeleton encased with glass, that would minimize the pressure on the original site.

[Figs 54–56, archeological sites on display and new tower exterior and interior]

St Joseph Cathedral in Wuhu after this. One colleague seemed underwhelmed by this church. Perhaps a Catholic church simply does not count as “Chinese” architecture in the proper sense? It is a rather sober-looking Gothic cathedral perched on the lower reach of the He’er Hill facing the Yangtze River in Wuhu, built in 1895. Flanked by two 29-meter tall towers is a five-meter white marble statue of Jesus right above the gable. The cathedral itself tells a story of vicissitude in its century-long history. The construction of the original cathedral was started in 1889, after the city of Wuhu was opened as a treaty port following the Sino-British Chefoo Convention signed in 1876, as a measure to resolve the Margary Affair (a diplomatic crisis triggered by the murder of the British official Augustus Raymond Margary the previous year). The aggressive stance of the French Jesuits led by Joseph Seckinger (1829–1890), however, elicited resistance from the local population of Wuhu who burned down the cathedral in 1891 before it was completed. Subsequent indemnity from the Qing government following the treaty allowed the Jesuits to build the current cathedral, recently restored in 1993, on a grander scale.7 Appropriated during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), it was restored and reopened to the public in 1983. A major restoration was carried out in 2003, and ten years later, it was added to the National Register of Historic and Cultural Sites in China(Quanguo zhongdian wenwu baohu danwei, 全国重点文物保护单位). It is now the second largest Catholic cathedral in Eastern China with active service.

[Figs 57 & 58, pics of St. Joseph’s at Wuhu exterior and interior]

A 4-hour bus ride afterwards took us from Wuhu to Huangshan (Tunxi) for the next part of our trip.

Day 8, January 3. 2018, Huangshan to Hangzhou, rain

In the morning we saw two great old villages, first Nanping, and then Hongcun, both in Yi County of Anhui Province. We went to Nanping first, a village with a history stretching back over 1000 years, which still has over 300 traditional vernacular buildings surviving from the Ming and Qing periods (roughly mid-14th century to early 20th century). Nanping Village is known for its tightly knit, maze-like network of alleyways with fine architecture, especially its collection of ancestral halls, which could be represented by the Ye Family’s Ancestral Hall and Branch Ancestral Hall, that we visited. People in the village also make it known that theirs was the chosen sites for some very famous film scenes including some in Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

The picturesque Hongcun nestles at the foot of a hill not far from Nanping. This village likewise enjoys a long history (about 800 years), and flourished with sustained development by successful merchants and imperial scholar-officials from the village. Especially during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the salt and tea merchants from this region who virtually monopolized these trades, and many Confucian scholars who acquired high positions first in the imperial examinations, and then in official posts, built sumptuous houses after their retirement. A large artificial lake (South Lake) welcomes the visitor with its serene beauty on the south side of the village. The placid water reflects the houses, plain and elegant with black tiles and white-washed walls. The overall layout of the village is anchored in another body of water at the center of the village, the much smaller, half-moon shaped Moon Pond that is only about 1.2 meters deep and 130 meters in circumference. In fact, water is everywhere in the village. The intricate and highly efficient waterways in the village provide fresh water supply to every household.

[Figs 59 & 60, picturesque Hongcun from the south, and the Moon Pond]

About 130 old houses survive more or less intact in the village of Hongcun today, and for a student of Chinese architecture, the village is a wonderful depository of folk and vernacular knowledge and regional culture accumulated over a long period of time. It has not “organically grown” as one might expect; rather, the current street pattern and waterways of the village were comprehensively laid out at the beginning of the 15th century by a Fengshui master who was hired for the purpose. A comprehensive water system was built channeling water from the river flowing on the northwest of the village, bringing water to every household through a complicated system of canals totaling 1200 meters in length. The Moon Pond was dug to receive the canals before the waterway was directed to the South Lake which was also built as a strategic part of the plan, to relieve the water for irrigation and final discharge into the river that embraces the village on the south.

[Figs 61–63, tourist map of Hongcun showing plan of village, and pics of house, and canal next to houses, notice the relation of house and water]

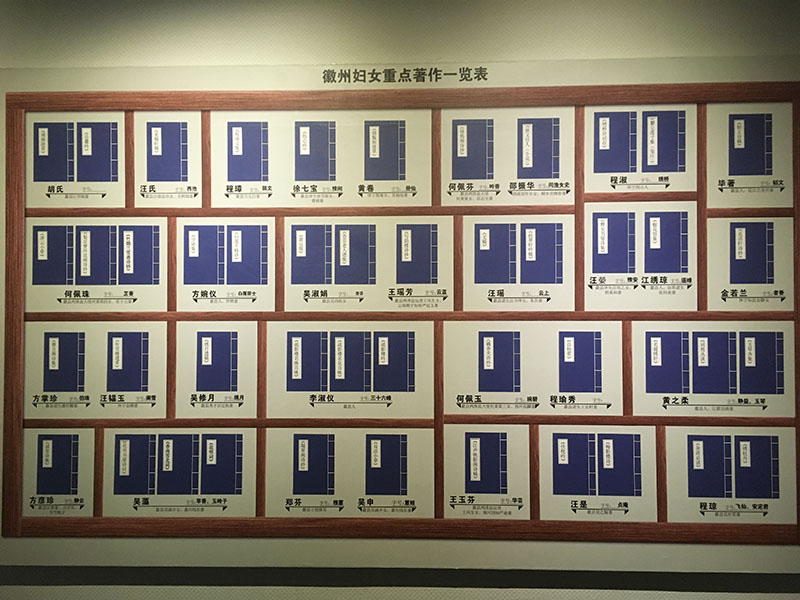

A quick visit to the Huizhou Culture Museum afterwards helps put what we learnt at and about the villages into a broader framework and more precise perspective. For instance, we learnt from our local tour guide that Ming and Qing women from this region were really the pillars of households and local community in the absence of their itinerant husbands on business or official duty. At the Wang Family’s Ancestral Hall at Hongcun, we saw a hanging stroll of a woman’s portrait, an anomaly indeed because the Neo-Confucian patriarchal rites prohibited a woman’s presence in the ancestral hall, except under very special circumstances. But the woman in the portrait, a Mrs. Hu, was virtually the architect of the comprehensive planning of the village at the beginning of the 15th century. Being the wife of the clan elder who was out on his official post year round, she was in charge of village affairs, and yet, although aware of the necessity for Fengshui planning, she herself could not practice Fengshui, a vocation reserved for men. She therefore invited the Fengshui master, a friend of her father’s, to take on the project. Village descendants recognized her contribution to their welfare and honored her by inducting her portrait into the ancestral hall. In a rare kudos, a plaque above her portrait describes her as a “Female Man.” (Jinguo zhangfu, 巾帼丈夫) At the Huizhou Culture Museum, we likewise learnt about women’s contribution to the regional culture in terms of not only the traditional “feminine” endeavors such as embroidery, but also literary achievement, with a gallery wall devoted to the most important literary works of women from the Huizhou area.

[Figs 64 & 65, Mrs. Hu’s portrait and Huizhou women authors’ works at the Huizhou Culture Museum]

A bus ride then took us to Hangzhou, the city on the beautiful West Lake.

Day 9, January 4, 2018, Hangzhou and Ningbo, rain

We walked in the rains to the former residence of Hu Xueyan (1823–1885), a well-known merchant who first made his fortune in banking, and later expanded it in grain, real estate, salt, tea, clothing, and arms trade through his connections with high-ranking officials of the imperial Qing court. His residence was first built in 1872 at the height of his power and prosperity, an unabashed example of late Qing luxury garden-residence through and through. Occupying a lot a little less than 2 acres, the garden-residence complex was nevertheless tightly packed with buildings, courtyards, and gardens creating complex and intriguing spaces.

Here space is literally layered by the visually intriguing rooflines, intentionally creating ambiguity in spatial depth.

[Fig 66 space in Hu’s house]

And here the undulating wall and straight lines of the courtyard floor combine to create an optical disruption to the visitor.

[Fig 67, more space inside Hu’s house, notice where the corner of the wall meets the floor]

The wealth of the owner was everywhere on display in the house, in the materials of construction, furnishing, and equipment. The building complex displays fondness for Western ideas and materials, as befitting the owner’s business dealings with foreigners. The stained glass, for example, furnished profusely in the house, was imported from outside China, a symbol of wealth and social standing. And ah, did we hear enough about Hu’s concubines from our local guide!

[Fig 68, stained glass inside Hu’s house]

We then visited the Silk Museum, originally opened in 1992, and then in 2016 after an extensive renovation project. It is the first national thematic museum of its kind in China and the largest in the world. The exhibits are breathtaking with displays of the historic development of sericulture, weaving, and embroidery from ancient China to the present, from its techniques to the various machineries used, and of silk fashion from the West to the East.

The Tianyige Library, which we visited after the museum today was originally the private library of Fan Qin (1506–1585), a Ming-dynasty politician, bibliophile and scholar, who established it during 1561–1566. Now home to about 300,000 volumes of books and numerous items of historic and cultural significance, it is the oldest private library in China and one of the oldest surviving private libraries in the world.

The Baoguo Monastery, perched on the small hilltop of Lingshan outside the city of Ningbo, really demands at least a full day in order to do it justice. The main hall of the monastery is a rare example of a Northern-Song dynasty (960–1127)timber construction on the South of the Yangtze River, built in 1013. Some examples of carpentry are among the only ones surviving from such an early period, including the melon-wheel-shaped pillars (an ingenious solution to the problem of lack of large-size timber), the curved beam and the four-step bracket sets. The chanduchuomu seen in this hall is the singular

example of such a member in Chinese architecture.

[Figs 69–71, pillar, bracket sets and chanduchuomu at Baoguo Monastery]

The monastery draws flocks of architecture students because of its historic value in illuminating the Yingzao fashi, the iconic building manual from the Northern Song dynasty published about 90 years after the construction of the hall, stipulating construction techniques, painting, and labor and material evaluation. But we had less than an hour, and it was getting quite dark.

Day 10, January 5, 2018, Hangzhou to Guiyang, rain

We stopped by the Hangzhou International Conference Center for about 15 minutes on our way to the airport to Guiyang where, upon arrival, we were taken to the Qingyan Ancient Town directly. This is an early Ming dynasty garrison first built over 600 years ago, with a section of the old wall, and some old buildings still standing. But the majority of the buildings in town seem heavily restored or brand new. This was also where a colleague and I saw what he called “instant antiquing,” the practice of a carpenter “spraying” a tube of flames on a newly finished wooden window to make it look dark and old instantly. Here the gaudy entrance of the Daoist Monastery Wanshou gong stands as an example of “fake antiques” everywhere seen in China today.

[Figs 72–74, Qingyan town, wall with gate, faking antique, wanshou gong]

Professor Steinhardt gave a great lecture tonight on the gardens and pagodas, especially in Suzhou, providing a nice review of what we just saw, and another short one on Yangzhou’s architecture.

Flight from Guiyang to Guangzhou.

Day 11, January 6, 2018, Guangzhou, a lot of rain

The first item on the itinerary today was the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Guangzhou, designed by the same architect who designed his mausoleum in Nanjing, Lv Yanzhi, and built in 1929–1931. Here as in the mausoleum complex in Nanjing, we see the architect’s intention and effort to adapt the traditional Chinese building to foreign use; i.e., that of a large-size auditorium. The main entrance side of the building presents a rather curious assortment of rooflines and wall surfaces. The dominating red and blue color scheme is a nod to the stateliness and dignity of palatial Chinese architecture, but the proportion is determined by the functional requirements of the auditorium, whose roof spans over 40 meters, a steel-reinforced frame without any columns. In fact, the auditorium was the largest in China—with the best acoustics—when it was built.

[Figs 75 & 76, pics of auditorium exterior and interior]

The exhibition of the Western Han Nanyue King’s tomb museum was absolutely stunning! Nanyue was a kingdom that ruled the majority of present-day Guangdong, Guangxi, and parts of Fujian, and the surrounding southern parts from about 204 BCE to 112 BCE, with its capital city in today’s Guangzhou. The burial ground belonged to Zhao Mo (r. 137–125 BCE), the second king of the kingdom. Excavation of the tomb produced a stunning array of funerary objects including a jade suite on the king’s body, and over 1000 other items, including a large quantity of jades, precious metals such as gold, silver, brass, and pottery objects.

[Figs 77–79, Nanyue king’s tomb and excavations]

The bus drove past the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Guangzhou, as the majority of the group voted “pass” for this site. We went to Zhujiang New Town (Zhujiang xincheng, 珠江新城) instead, to see the Opera House designed by Zaha Hadid and the other new buildings that have sprung up in a matter of less than 20 years. Brand-new office buildings, five-star hotels, super-sized shopping malls, government and cultural institutions are squeezed tightly into an area a little over 6 square kilometers, each calling attention to itself. We walked around the opera house for about 10 minutes before heading over to the new library that opened in 2013. We were all drenched in the rain during the 5-minute walk from the library back to the bus.

[Figs 80–82, pics of Zhujiang xincheng]

This day concluded our field trip. The majority of the group went to Hong Kong to go their own ways. Seems like a fitting place to stop and pause a while. We visited so many places and saw so many different things during this short trip. Ancient 2000-year-old structures were experienced on the same day as the most contemporary architecture, and humble vernacular houses shared similar spatial organization as the Forbidden City. If my question posed at the beginning of the blog, i.e., “What is Chinese architecture in the 21st century?” still stands, could we say that everything we have seen belongs in the category of Chinese architecture? Even Zaha Hadid’s Opera House?

China today does have the guts and appetite to claim everything built in its territory as “Chinese” architecture. Or to put it slightly differently, Chinese architects today, and perhaps the public as well, do not seem as bothered by questions of style, form, national character as their predecessors in the, say, Republican period were? Why?

I needed to get back too. I took a taxi to the airport by myself, and started talking to the driver, a Guangzhou native, about what I had seen in Guangzhou the previous day. I asked him about Zhujiang New Town, and he said, “Don’t you know that every major Chinese city is building a New Town now?” He was right; if the so-called first-tier cities in China, the likes of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, started the trend, they will be followed soon by every other city that aspires for the mega-city status.

But aren’t places like Zhujiang New Town only a presentable mask that the Chinese government wants the world to see? One wonders what is hidden by the face of ostentatious and sleek modernity. When it comes to Chinese architecture specifically, what is it that we are not allowed to see and know?

Yan Wencheng received her PhD in the history of art and architecture from University of California, Santa Barbara in March 2016. Her dissertation, entitled Writing Modernity: Constructing a History of Chinese Architecture, 1920–1949, examines architectural historiography of modern China by excavating and analyzing a set of popular discourse vibrant during this period but subsequently lost in the standard history of Chinese architecture. Her interest in vernacular architecture is partly due to what she had seen in a two-week self-guided vernacular architecture tour in southwestern China over ten years ago, partly because of her conviction that it deserves more scholarly attention, and partly because of the theoretical and substantive potential of vernacular architecture in informing us about global sustainable architecture and urban planning in the twenty-first century. She is also interested in cultural translation among different architectural traditions in the modern and contemporary periods.

1 Liang Sicheng, “Jianzhu de minzu xingshi,” (The national form of architecture) in Liang Sicheng, Liang Sicheng quanji (Complete Works of Liang Sicheng) vol. 5. Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe (2001) : 55-59.

2 For an introduction to this burial style, see Aurelia Campbell, “The form and function of Western Han ‘Ticou’ tombs,” Artibus Asiae, 70:2 (2010): 227–258.

3 See Delin Lai, “Searching for a modern Chinese monument: the design of the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in Nanjing,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 64:1 (March 2005): 22–55.

4 The influential Chinese journal Jianzhu xuebao [Architectural Journal] ran a special issue focusing on the Grand Bao’en Monastery in early 2017, which included several articles by the design team members. See Chen Wei, “Lishi ruci liudong [History flows as it should],” Architectural Journal (2017.1): 1–7.

5 A Southern Weekly article discusses the project in 2011, after it received the one-billion-yuan donation making it possible to start the project for real, focusing on the tension between conservation of the historic site and reconstruction of the pagoda. The last section of the article is titled “Hugely Profitable,” discussing the potential economic and financial profit of the project. See Ju Jing, and Hu Han, “Controversies on Reconstructing the Grand Bao’en Monastery of Nanjing—Cultural Protection and Tourist Attraction: Which Matters More?” (In Chinese), The Southern Weekly, April 25, 2011, http://www.infzm.com/content/58070.

6 Ms. Ren gave us this information, and I haven’t been able to find more details about it. See an article on CNN about the park. Elaine Yu, CNN, “China rebuilds a 'world wonder' in Nanjing.” Updated 21st September 2017.

7 A 1984 article gave a detailed account of the bloody conflict that happened at the St. Joseph Cathedral in 1891. See Weng Fei, “Wuhu jiaoan [Wuhu’s Catholic Conflict],” Historiography Anhui (1984.2): 48–51.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top