-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Study Day: MoMA and UN Headquarters (Newsletter Report)

The Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibition, Latin America in Construction: 1955-1980, marks the first time since 1955 that the institution has presented architecture in Latin America. Participants in SAH’s MoMA/UN Study Day on March 27, 2015 were treated to a preview of the show by Dr. Barry Bergdoll, then-Chief Curator of Architecture and Design and currently a professor of architectural history at Columbia University. The goal of the show, he said, was to recalibrate the notion of “Latin America” as an architectural adjective toward a more nuanced understanding of both the parallels and differences in the built environment of all countries in the region. The story of architecture in Latin America, as told by Dr. Bergdoll and revealed through the MoMA exhibition, fits squarely with my interest in a broad exploration of the center-periphery split in modern architectural historiography and the related international-regional divide in modern architecture. The exhibit’s fresh look at architecture in Latin America, rather than “Latin American” architecture,1operates at this intersection of center-periphery issues between the United States and Latin America and within the international-regional modernism debate that was playing out in the US at the time.2

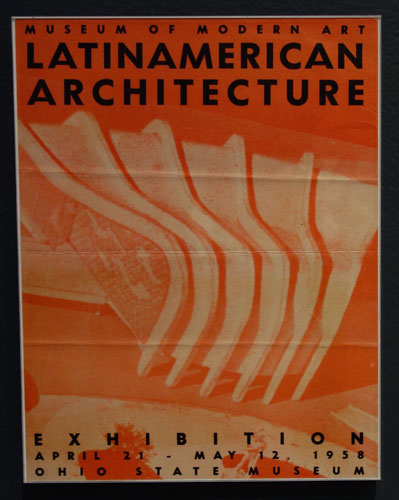

Figure 1. MoMA poster advertising the 1955 exhibition Latin American Architecture Since 1945

The inventive forms and robust individualism of the architecture in Latin America developed in the early years of the modern movement captivated both the public and critics. The Brazil Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair seemed to point toward “a wholly new experimental modernism,”3 while the completion of the Ministry of Public Education and Health in Rio in 1943 caused Le Corbusier to proclaim that “the [architectural] torch has been passed.”4

Figure 2. Model of the Brazilian Ministry of Education and Health, completed in 1942 by a team of architects including Oscar Niemeyer, Lucio Costa, and Le Corbusier as consultant

The Museum of Modern Art played a seminal role in the dissemination of architecture in Latin America, first through the 1943 exhibition Brazil Builds and then through the 1949 exhibition From Le Corbusier to Niemeyer, 1929-1949. This exhibition coincided with the construction of the United Nations Headquarters building in New York City, which was designed by an international team of architects that included Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, and Julio Vilamajo. By the time of the 1955 MoMA exhibition Latin American Architecture Since 1945 most of Latin America was steadily committed to modern architecture, causing MoMA Director of Architecture and Design Arthur Drexler to remark that the quality of architecture in Latin America had surpassed that of the United States.5

At the midcentury mark interest in the region took a turn toward the negative, however, as the United States shifted its post-war political interests and fractures within modern architectural discourse began to emerge. In 1948 MoMA held a symposium titled “What is Happening to Modern Architecture?” in order to respond to challenges by critics such as Lewis Mumford, who called for greater attention to regionalism and contextualization in modern architecture.6 The New Empiricists in Sweden were calling for a more humanized approach to modern architecture7 while Walter Gropius and Joseph Hudnut were fighting it out over the direction of modern architectural education at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.8 In 1951 Henry-Russell Hitchcock, co-definer of the International Style, found himself trying to justify and salvage its tenets9 and by 1954 American and European architectural critics expressed concern over the individualist and “disordered” modern forms developing in places like Latin America.10 The exclusion of Latin American architecture from MoMA’s 1932 Modern Architecture: International Exhibition presaged these competing strains within the field, signaling what would become a narrowing of acceptable modern architectural form language. Latin American architecture, once offering “a veritable crucible of new inventions in the forms of modern architecture,”11 became a lightening rod for criticism within the larger architectural discourse before facing eventual marginalization within the modern architectural canon. MoMA’s new exhibition on architecture in Latin America utilizes a more contextual approach in order to move the modern discourse beyond traditional stylistic and formal interpretations of narrowly curated ideals, dismantling foundational prejudices that have previously informed the historiography of the region.

Figure 3. SAH MoMA/UN Study Day participants examining MoMA’s new exhibition Latin America in Construction: 1955-1980

Jennifer Tate, PhD Candidate, University of Texas

Jennifer Tate, PhD Candidate, University of Texas

Jennifer Tate is a PhD candidate in architectural history at the University of Texas in Austin. Jennifer holds a master's degree in architectural history from the University of Texas in Austin, as well as graduate degrees in political science from Georgetown University and international policy studies from Stanford University. She received her BA with honors in political science and mathematics from Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. Jennifer is interested in the intersection of politics and power relations with architecture, especially in the examination of center-periphery issues and the related international-regional divide in modern architecture. She has a secondary interest in modern Turkish architecture.

1. see Luis Carranza and Fernando Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

2. “What is Happening to Modern Architecture?” The Bulletin of The Museum of Modern Art, XV, no. 3 (Spring 1948), in Vincent Canizaro, ed., Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 292-309.

3. Barry Bergdoll, “Learning from Latin America: Public Space, Housing, and Landscape,” in Barry Bergdoll, Carlos Eduardo Comas, Jorge Francisco Liernur, and Patricio del Real, eds., Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2015), 17.

4. Barry Bergdoll, SAH MoMA/UN Study Day Tour, The Modem of Modern Art, New York, NY, March 27, 2015.

5. Berdgoll, “Learning from Latin America,” 18-19 and Arthur Drexler, “Preface and Acknowledgments,” in Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Latin American Architecture Since 1945 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1955).

6. “What is Happening to Modern Architecture?” The Bulletin of The Museum of Modern Art, XV, no. 3 (Spring 1948), in Vincent Canizaro, ed., Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 292-309.

7. Anderson, Stanford, “The “New Empiricism – Bay Region Axis”: Kay Fisker and Postwar Debates on Functionalism, Regionalism, and Monumentality,” Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 50, No. 3 (February 1997), pp. 197-207.

8. Pearlman, Jill, “Joseph Hudnut’s Other Modernism at the “Harvard Bauhaus”,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 56, No. 4 (Dec. 1997), pp. 452-477.

9. Hitchcock, Henry-Russell, “The International Style Twenty Years After,” Architectural Record, Vol. 110, No. 2 (August 1951), pp. 89-97.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top