-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Kahn Tour: Illumination

Despite his pronouncements on “silence and light,” in his 1931 sketching article Kahn is surprisingly silent about light.

The works we visited, however, speak volumes. Compare, for example, a modest early building and two major, later works: the Trenton Bath House (1954-1959), Yale University Art Gallery (1951-1953), and the Yale Center for British Art (1974-1977).

The bath house was designed for summer use, and the strong, high light of July emphasizes the structure’s mini-monumentality. Here one can imagine the legendary light of Greece, recalled by the bath house’s cruciform plan, open promenade, and central fountain (now lost).

It should be noted here that Anne Tyng played a significant and under-appreciated role in the bath house design, contributing among other things geometry and the elegant corner entries to each changing room, all of which underpin the light effects. An associate recalls that “…Kahn was having trouble with the design [and] Tyng was heard calling…that she ‘had something.” Kahn walked over and…’immediately saw that Anne’s design was it.” (See Carter Weisman. Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, p. 93.)

Entering the changing room at Trenton, Tyng’s corner entries transition beautifully to the shade and cool of the changing area (while eliminating need for doors and their maintenance). Yet the skylight brings in a soft light (eliminating the need for fixtures, too). In contrast, sharp slivers of light pierce the rough concrete walls, stabbing through the gap between walls and floating roof.

How different from Kahn’s museums at Yale, especially the diffuse glow in the galleries of the Yale Center for British Art. Natural lighting was a shared goal with the clients. In fact, it was a requirement for the painting galleries. The desire for a domestic scale was also a factor (presumably the corresponding light effects were desired as well). In the preliminary phase of the design, Kahn visited homes of patron and collector Paul Mellon, as well as the Phillips Collection, a house-museum in Washington, DC. The YCBA glow is the product of the large-span skylights and their deep pyramidal wells. The 20-foot spans help to break the spaces up into room-sized galleries, but moveable, floating partitions and louvered windows keep the feeling open and of course, light. The skylights illuminate the top galleries and atrium. In turn, atrium overlooks allow light to enter galleries on lower floors. White oak panels and smooth concrete complete the effect.

In this rendering I tried to capture the glow and minimal shadows. Watercolor is an excellent medium for exploring light effects, for its luminous quality comes from the paper’s reflectiveness. Watercolor filters this light like stained glass, unlike opaque media.

Kahn’s sketching article features mostly pastels and charcoals (all reproductions are in black and white, unfortunately). His European pastels express the feel of light on rough materials, and they seem a particularly appropriate choice for eroded stone and sandy landscape. (An aside: these sketches are striking for areas of vibrant color. Less well known is that in later life, cataracts affected his color vision. After treatment, Kahn declared, “I haven’t seen colors in years!” (Weisman, p. 86)).

The raw concrete of the Yale Art Gallery evokes the feeling of ancient stone, but without the bright light of their sites. The somber feeling is much different from the YCBA. At the Gallery the low, heavy concrete ceiling grid (innovative though not structural) and peripheral windows strongly absorb light. Here material spends light, leaving little for art. (Apparently there was enough light to spend some of the art materials, however–several works have been damaged over the years). The one exception is the well-known barrel stairwell, with its side-lit skylight. Here the light is diffused by glass block and curving walls. The light penetrates down several floors, giving a sense of ascent and descent.

As a student of museum history, i wonder if Kahn knew of historical precedents in natural lighting for museum galleries. Certainly he experienced the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (Frank Furness, 1876). Did he visit Memorial Hall in Fairmount Park, the glass-domed remainder of the Centennial Exhibition (H.J. Schwarzmann, 1876)?

One wonders in particular if he was aware of John Soane’s inventive use of indirect light, in his wonderful house-museum (1792-1824) or at the Dulwich Picture Gallery (1814), known as the first purpose-built art gallery. Probably not. His influences tended to be ancient and his guidance internal. According to several sources Kahn said, “I am an interesting kind of scholar because I don’t read and I don’t write.”

The raw concrete of the Yale Art Gallery evokes the feeling of ancient stone, but without the bright light of their sites. The somber feeling is much different from the YCBA. At the Gallery the low, heavy concrete ceiling grid (innovative though not structural) and peripheral windows strongly absorb light. Here material spends light, leaving little for art. (Apparently there was enough light to spend some of the art materials, however–several works have been damaged over the years). The one exception is the well-known barrel stairwell, with its side-lit skylight. Here the light is diffused by glass block and curving walls. The light penetrates down several floors, giving a sense of ascent and descent.

As a student of museum history, i wonder if Kahn knew of historical precedents in natural lighting for museum galleries. Certainly he experienced the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (Frank Furness, 1876). Did he visit Memorial Hall in Fairmount Park, the glass-domed remainder of the Centennial Exhibition (H.J. Schwarzmann, 1876)?

One wonders in particular if he was aware of John Soane’s inventive use of indirect light, in his wonderful house-museum (1792-1824) or at the Dulwich Picture Gallery (1814), known as the first purpose-built art gallery. Probably not. His influences tended to be ancient and his guidance internal. According to several sources Kahn said, “I am an interesting kind of scholar because I don’t read and I don’t write.”

One imagines that Kahn would have appreciated Soane. Both architects were intuitive and idiosyncratic. Both sought the sublime. Both appreciated but transcended ancient precedents. Both were influential teachers. And they both developed unprecedented techniques for indirect natural illumination.

Someday I hope to visit the Kimbell (1966-1972), known as Kahn’s greatest achievement with light. What is the combined effect of Texas sun, barrel vaulting, and Kahn’s ingenious skylights? How does this change our perception of the works on view? And can I sketch in the galleries?

On this note I end these posts on “The Value and Aim of Sketching.” I hope they’ve conveyed some of the value of the SAH Kahn Tour.

Image (top): Jennifer Tobias. Trenton Bath House.

Image (second from top): Jennifer Tobias. Yale Center for British Art.

Image (third from top): Jennifer Tobias. Yale University Art Gallery.

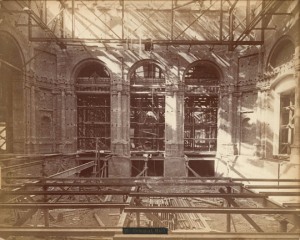

Image (fourth from top): Memorial Hall, 1875 (H. J. Schwartzman, 1876).

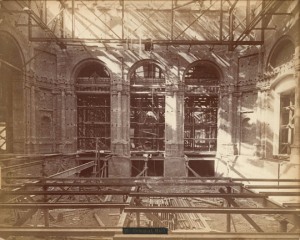

Image (bottom): Dulwich Picture Gallery (John Soane, 1814).

Image (bottom): Dulwich Picture Gallery (John Soane, 1814).

See Louis Kahn. “The Value and Aim in Sketching.” T-Square Club Journal of Philadelphia. May 1931, 18-21.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top