-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

A Broken Silhouette

This article originally appeared on the blog Stambouline and has been republished here with permission. Stambouline is dedicated to exploring the art and architecture of the Ottoman Empire, looking at the stories behind the buildings and objects that have been left behind. Each post introduces a new place or object. The main contributor to the blog, Emily Neumeier, is a graduate student studying the history of art at the University of Pennsylvania.

Istanbul's new Metro Bridge and the political battle over the city's historic panorama

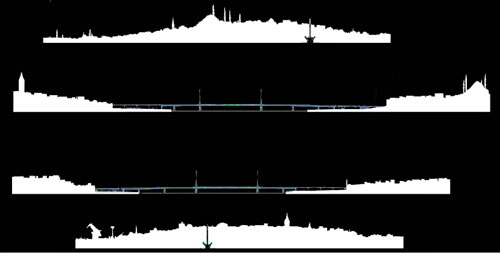

[1] Different profiles of the new Metro Bridge across Istanbul's Golden Horn, showing how the bridge would affect the different silhouettes of the surrounding site. Adapted from a graphic by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, 2009.

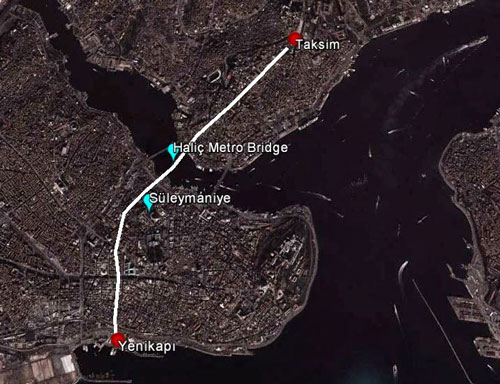

On February 15th, Istanbul's new metro line officially went into service. The project, initiated by the Greater Istanbul Municipality in 2005, unites the city's various metro lines, extending trains in Taksim Square directly into the old city, with connections to Atatürk Airport and the opposite Anatolian shore. [Fig. 2] While the majority of this new extension runs unseen underground, the most visibly prominent feature of the line is a bridge extending across the waters of the Golden Horn (Trk. Haliç). This past autumn, residents watched as the two 65-meter-tall pylons, supporting the bridge in a cable-stay system, slowly rose into the sky. At the opening ceremony last month, Turkey's Prime Minister Tayyıp Erdoğan was quoted saying "for this metro line, we constructed a bridge on the Haliç that will enhance Istanbul's beauty." The Prime Minister was also careful throughout his speech to stress that every precaution was taken so as not to harm any of the monuments "in an area harboring a history spanning thousands of years." These platitudes about the importance of protecting Istanbul's cultural patrimony were no doubt crafted in direct response to the backlash of scathing criticism that the bridge design faced from not only the local press and academic community, but also a UNESCO mission whose findings threatened to land Istanbul on the list of "World Heritage Monuments at Risk." The main concern lodged against the new Metro Bridge is that certain features (particularly the tall pylons, suspension cables, and rail station in the center of the bridge) block the view from the north towards the historic peninsula of the old city, especially the 16th-century Süleymaniye Mosque Complex. [Fig. 3] Erdoğan would call this addition to the old city's skyline an enhancement; others, an obstruction. As one of the major projects that the city's top brass rushed to completion to meet the deadline of the March 30 municipal elections, the Haliç Metro Bridge and Istanbul's historic skyline are a case study in how the current government's massive infrastructure projects have become a tense political battleground.

[2] Map Showing the new metro extension from Taksim to Yenikapı. Drawn in Google Earth.

[3] The Haliç Metro Bridge, March 2014. Looking from the shore of Beyoğlu onto the historic peninsula, the bridge partially obstructs the view to the Süleymaniyye Mosque. Photo by Emily Neumeier.

[4] Original design proposed for the Haliç Bridge, 2007. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality.

In 2007, the original designs for the bridge by Hakan Kiran Architecture were revealed. [Fig. 4] The plans proposed two gilded 82-meter-tall pylons, which curved at the top into "horns" (Get it? Because the bridge is crossing the Golden Horn). Unfortunately for the Greater Istanbul Municipality, UNESCO does not seem to have a similar sense of humor when it comes to visual puns. The city's historic peninsula, which is clearly defined by the old land and sea walls, was inscribed on the register of UNESCO's "World Heritage Sites" in 1985. Because the new bridge would impact the view to the peninsula from the north, and construction would require the demolition of several historic buildings within the core area, the organization decided to step in. UNESCO made it clear that if significant changes were not made in the proposed bridge design, this project could demote Istanbul to the similarly-named but decidedly less-fun list of "World Heritage Sites in Danger," joining the illustrious company of Bamiyan and Damascus. So, the architects on the project scaled down the plans, most notably lowering the height of the bridge's pylons by about 20 meters, and changing their color from a golden yellow to a grey-white tone. With a few other minor alterations, this is basically what we see built on the ground today. The report from a joint UNESCO/ICOMOS monitoring mission to Istanbul in 2009 gives a sense of the farcical proceedings. When the investigators inquired after the cable-stay design, curious if any other options had been considered:

The mission was informed that 11 alternative designs [for the bridge] had been presented to the Conservation Council, but the alternatives were produced 10 years ago and were not studied proposals – they were only suggestions. Some of the suggestions were just copied and pasted from books on bridges. It seems clear that no alternative design has so far been seriously considered and, with regard to the design of the current proposal for a cable-stay bridge, during the meeting it was stated that the intention was to 'introduce a new work of art – a new contemporary element in the area.' [34]In 2011, UNESCO finally approved the construction of the Metro Bridge, lending legitimacy to the project's backers. (Congratulating themselves on a job well done, the organization proceeded to be completely out to lunch on the destruction of the Yedikule gardens and the lightning-fast construction of a 270,000 square meter platform protruding into the Marmara Sea, which was inaugurated with an 1.5 million-person rally on March 23.) Many local critics, however, still felt that the changes in the design did not adequately address the primary concern of blocking the northern view to Istanbul's peninsula [Fig. 5], again summed up in the 2009 report:

The overall design of the bridge, with pylons and cable stays and the thickening of the deck through the incorporation of a station, will have a significant visual impact on key attributes of the property such as the silhouette of the Historic Peninsula...the design of the bridge is inappropriate for this position, both because it will impede irreversibly on many important views of the World Heritage Site and because the bridge, presented as a 'work of art,' will compete with the Süleymaniye Mosque, identified at the time of inscription as a work of human genius, designed by Sinan. [34-35]

[5] View of Istanbul's historic peninsula, looking from Galata. Abdullah Fréres, ca. 1880-93, Library of Congress.

[6] View of the Inner Courtyard of the Süleymaniye Mosque. Photo by Michael Polczynsky, 2014.

The Turkish press and local academics expressed outrage about the bridge's potential to impede on the visual integrity of the peninsula's skyline. There has been no shortage of colorful metaphors; according to various critics, the bridge threatens to "break", "stab", and "violate" the silhouette of the old city. In the eyes of many, the pointed tops of the pylons are not horns, but daggers, slicing the panorama into two. This visceral imagery characterizing the landscape as a prone body vulnerable to violent attack is a familiar leitmotif, especially in the wake of modern warfare and the large-scale urban planning projects of the 20th century. In her article on the "ideology of preservation" in Istanbul, Nur Altınyıldız traces how in the 19th century the large mosque complexes dotting the hills of the peninsula [Fig. 6], which originally were service-oriented institutions and themselves agents of urban growth and renewal, were increasingly divorced from this service context and re-classified as "historic" monuments whose preservation stood at odds with the modern signifiers of progress such as opening new roads (or new metro bridges). [234]

[7] View from the Süleymaniye Mosque Complex to the Golden Horn. Photo by Michael Polczynsky, 2014.

As the UNESCO report alludes, and commentators frequently point out, the silhouette under question is an Ottoman contribution to the city. When Sultan Süleyman commissioned the Süleymaniye (c. 1550-1558) on the top of Istanbul's third hill, he was following the precedent established by his predecessors Sultan Mehmed II and Bayezid II, who had constructed their own mosque complexes along the ridges of the peninsula in the 15th century. Significantly, the Süleymaniye complex was originally designed so that the auxiliary buildings flanking the mosque on its northern side, towards the Golden Horn, were constructed on a lower terrace so that the monument would have an unobstructed view of Galata, Üsküdar, and the Bosphorus [Necipoğlu, 106]. [Fig. 7] In this unmistakable declaration of power, the mosque, as a stand-in for its sultanic patron, commanded a wide gaze and likewise demanded to be seen. It is certainly no coincidence that the "audience" on the opposite shore of the Golden Horn was largely composed of foreigners and non-Muslim communities, who from their perch in Galata were always to some extent on the outside looking in to the city proper. Throughout the centuries, European cartographers and artists endlessly recorded this view, the Golden Horn panorama becoming its own veritable genre in the imagery of Istanbul. Now that the heart of the modern city has shifted to the area around Taksim Square, it could be argued that what was once the purview of foreigners, and Ottoman elites in the 19th century, has now been democratized (or, more cynically, commodified), becoming a monument deserving preservation in its own right.

[8] A sign advertising the opening of the Haliç Metro Bridge. The slogan reads "The Metro Everywhere, the Metro to Every Place." Under the slogan is the name and signature of the Istanbul Mayor, Kadir Topbaş. Photo by Emily Neumeier.

Some people are wondering what the fuss is all about. The Mayor of the Greater Istanbul Municipality Kadir Topbaş points out that, in truth, the view of the Süleymaniye is only obstructed from specific vantages, primarily the Beyoğlu neighborhoods just west of the new bridge. (read: tourists don't go there, so why is everyone getting upset?) On the other hand, Edhem Eldem wonders at the public outcry when the Süleymaniye or the starchitect Sinan's genius is threatened, but the relative silence to the arguably much more egregious destruction of Byzantine-era material. The controversy is reminiscent of the frequent criticism lobbed at Santiago Calatrava's distinctive bridge designs, which are often cited for not taking the local context or geography into account, and, on top of that, being needlessly expensive and poorly-built. Almost a full month after the official opening, the Vezneciler stop on Istanbul's new metro line was still being completed. During such time, passengers traveling from Taksim over the Haliç Bridge were treated to a creepy view of the unfinished station, complete with flickering lights and tubes hanging from the ceiling.

[9] A view approaching the station on the bridge. Photo by Emily Neumeier.

A 2013 petition signed by faculty members of Istanbul's Boğaziçi University lists the Haliç Bridge as only one of many recent infrastructure projects that, the faculty argues, are being completed at such a fast rate and with so little public participation or accountability that the damage being done will be "irreversible." And that is precisely the point. It is the sincere wish of the bridge's designers (including Topbaş himself, trained as an architect) that this project will endure the test of time. Aiming to create a work of art that could rival the Süleymaniye, the current municipal government has done its best to insert their own contribution to the historic skyline, evidently full-aware of the site's significance to the public imagination of Istanbul. In hopes of finding some kind of press release on the opening of the bridge, I looked on the official website promoting the new bridge project. The website, unlike the bridge itself, was still under construction.

EMILY NEUMEIER is a doctoral candidate in the History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania.

**The report of the joint UNESCO/ICOMOS 2009 visit to Istanbul can be found here.

ALTINYILDIZ, Nur. "The Architectural Heritage of Istanbul and the Ideology of Preservation."Muqarnas 24 (2007), pp. 281-305.

GUIDONI, Enrico. "Sinan's Construction of the Urban Panorama." Environmental Design: Journal of the Islamic Environmental Design Research Centre 1-2 (1987): pp. 20-41.

KORKUT, Sevgi. "Istanbul's silhouette to change as metro line comes into view." Today's Zaman, 12 November 2012.

NECİPOĞLU, Gülrü. "The Süleymaniye Complex in Istanbul: ِAn Interpretation." Muqarnas 3 (1985), pp. 92-117.

VARDAR, Nilay. "Tüm İtirazların Ardından Haliç Köprüsü." Bianet, 24 January 2014.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top