-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

La Sagrada Família: A Testament of Architectural Ingenuity

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

By any standard, the Basilica and Expiatory Church of the Holy Family, also known as Sagrada Família, is every inch a miracle of architecture and construction. It is by far one of the most fascinating structures I have seen so far in my fellowship travels. In his work titled Gaudi, David Mower quotes the renowned architect and father of modern skyscrapers, Louis Sullivan. Sullivan called Sagrada Família the greatest piece of creative architecture and a spirit symbolized in stone.1 Possibly in no other building on earth—at least not at this scale—is the presentation of solid mass in organic form more perfectly delivered. More than just a basilica, the Sagrada Família is in every sense a living, breathing concrete mountain.

No matter which direction you approach the structure, you will very likely see the spires or, more appropriately, bell towers, from a distance. The towers, like aliens, lead you to what appears like a structure from another world. The characteristic cranes and scaffolds that adorn the basilica further add to its other-worldly posture. The Sagrada is not alien, it is merely different. The famed critic Zerbst Rainer once wrote about Sagrada Família that it is practically impossible to find a church building anything like it in the entire history of architecture.2 So different it is that it continues to rearrange our idea of what a building is or should be. So different it is that it defies common construction timelines and challenges. So different that it carries on a character of a living organism that continues to metamorphose right before our eyes. For over a century now, Sagrada Família has been a part of Barcelona’s landscape, almost the same as the Montjuic Hill. Unlike the Montjuic, however, Sagrada Família continues to grow. The tallest part of the massive structure will be the central tower called the Tower of Jesus Christ. In all, the basilica will have eighteen ‘desert plant’ looking towers: twelve representing the Apostles, four representing the Evangelists, one dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and the central and tallest is dedicated to Jesus. On completion, the Jesus tower will be surmounted by a large cross and its total height will come to an amazing 560 ft (172 m)—only a few meters short of the peak of Montjuic Hill itself. Gaudi is noted to have said that his creation must not surpass God’s.

I got into a tête-à-tête with a vendor near the Basilica, and he said to me, "You have come to Catalonia at a wrong time. The usual spirit of this place is no longer here. So much tensions these days. We fear for the tomorrow we will have, if there is going to be one. The spirit of Catalonia is dying," he adds. He said this in a mix of Spanish and English and he said it like he meant it. As I processed what he said and thinking to myself he must be referring to the recent and ongoing political tensions in Spain, he continued, "But if you have come to see Gaudi, he (Gaudi) is alive and everywhere!" To this, I could not agree more. For if any sense is to be made of what is arguably the most important landmark in Barcelona, drawing over 2.5 million visitors yearly, it is to Antonio Gaudi one must turn.

Fig. 1: Basilica and Expiatory Church of the Holy Family. Also called Sagrada Família. A view of the basilica from the eastern end, also referred to as the Nativity façade.

Fig. 2: A view of the basilica from the eastern end also referred to as the Nativity façade.

Fig. 3: A close up view of the basilica’s Passion façade of the western end. The angular sculpture featured here is by Spanish sculptor and painter Josep Maria Sabirachs who recently passed on in 2014.

Fig. 4: A close up view of the basilica’s Nativity façade of the eastern end.

Fig. 5: A close up of two of the four finished towers on the Passion façade. Both tower are well over 300ft off the ground.

Fig. 6: A view of the basilica from the northern end occluded by modern development. Here we see the tower of St Mary gaining height as construction continues. On completion, the tower will reach 404 feet above the ground.

Fig. 7: A view from the nave showing the rose window and part of the ceiling vaults.

Fig. 8: A view of the nave looking towards the altar. Notice the organic shaped columns. They look like tall forest trees with branches.

Fig. 9: Looking straight up in the nave, all one sees is a brilliant interplay of shapes and light. The vaults of the Sagrada Família.

Fig. 10: Parts of the treelike columns, the apse and the ceiling vaults. Interior of the Sagrada Família.

In 2015, Patricia Blessing, the 2014 H. Allen Brooks Fellow, visited Barcelona and Sagrada Família even when it was not centrally related to her research work as she said.3 Now I know why she did. Just like the vendor, Patricia had mentioned that Gaudi’s work was to be seen throughout all of Catalonia. A notable one is Casa Battló, fondly called the house of bones. This structure, however, does not match the grandeur and stateliness of Sagrada Família.

When you enter the Sagrada from the Northern end, also called the Passion façade, you immediately feel small and insignificant. The interior appears more majestic and mysterious that the exterior. Its ample use of irregular shapes and a mind-bending vault system is rather imposing and may take some time to take in. It has a strong affinity to a jungle, albeit a concrete one. Gaudi conceived the interior of the church as a huge forest, where the columns would be like tree trunk branching out from the capitals into the vaults, through which sunlight would filter, representing foliage (Jordi, 2016).4 The lights from the exterior sips in through openings and reflections creating a symphony of mixed coloured lights as you turn. And then the people. Hundreds of them with rumbling murmurs of different languages mixing together to form a consistent but barely audible mellow noise in the hollow sounding space. The sound is something that stays with you for a while. I have seen many cathedrals through my fellowship year but the number of people who have come to see Gaudi’s work is impressive to say the least.

Fig. 11: Tall columns transition into a network of angular shapes. Inside the Sagrada Família.

Fig. 12: Inside Sagrada Família. Tall treelike columns can be seen in the background.

Fig. 13: Illuminated Christ on the cross sculptural piece suspended from the nearby columns. On the canopy reads ‘Gloria A Due, A dalt Del Cel,’ which loosely translates as Glory to God in the Skies (Heights).

Fig. 14: A view of the altar from the nave. Notice the Christ on the Cross piece in suspension. Also notice the verticality of the columns even in their organic form.

Fig. 15: A view of part of the nave from the side of the high altar.

Fig. 16: In the nave of the Sagrada Família, people sit on the specially designed pews to take in the beauty of the interior.

The original design of the basilica expressed in Gothic style was the work of Francisco de Paula del Villar. Del Villar also started the building of the church in 1882 but resigned shortly after and this paved the way for Antoni Gaudi, who joined the project in 1883 and changed the design dramatically. Gaudi, the fragile little child born on in the summer of 1852, would later grow to be one of—if not the most—renowned Catalan architect in all of its history. Gaudi was a genius of his age and this ingenuity survived well after him as the architectural language he introduced continues to serve as a central guide for builders of the basilica years after. Though many contend with the latitude afforded the sculptors who appear to be exercising too great an artistic license in their interpretation of style on the Sagrada Família. Notable in the series of contentious works are the angular minimalist postmodern style sculpture of the Passion façade—very different to the naturalistic and emotive style employed in the Nativity façade supervised by Gaudi himself. Gaudi came to Barcelona in 1869 just as Spain was plunged into the unrests that led to the collapse of the monarchy. Working various jobs, he eventually became an architecture student in 1874 and quickly showed promise in the field.

They say Gaudi developed an incomparable personal style that defies classification. He takes the known and transforms it to an unknown. In the SagradaFamília, he starts the with guidance of the Gothic law and transmutes it into a neo-grotesque but living natural mass that continues to breathe and germinate into an organic system that calls your attention and leads you right into the mind of the artist himself. By the time Gaudi graduated in 1878, his genius had come to full bloom and possibly the penchant for overstepping the boundaries of architecture and design as was known then caught the attention of his tutors. Elies Rogent the director of the School of Architecture in Barcelona is famed to have said, “I do not know if we have awarded this degree to a madman or to a genius; only time will tell."

Fig. 17: The abstract geometric stained glass window design beautifully displays the colours of the forest. The colourful pieces are equally hosted by an abstract geometric designed wall.

Fig. 18: Geometric stained glass designs. Notice that each unit is named after a person or place of religious significance and relevance to the basilica.

Fig. 19: Classical Gothic style tracery hosts a more contemporary postmodern geometric abstract stained glass design. The Sagrada Família is in many ways a laboratory for stylistic experimentations.

Sagrada Família is a laboratory of sort for the experimentation of modernist ideas the Catalan way as defined by Gaudi. What the basilica lacks in naturalistic figural ornamentation, it made up for in its display of expressionism and symbolism. His work achieved a symbiosis between form and Christian symbolism with a peculiar architecture generated from new structures, forms and geometry, but one which included great logic and was inspired by nature (Jordi, 2016).5 Visual meaning expressed through the mimicry of nature is at its best here on the basilica. Gaudi chose the interpretation of movement and growth in nature as a vehicle to communicate a simple but fundamental theme in this piece, which is the centrality of family. Little can be argued against the uniqueness of this masterpiece. Gaudi, in this piece, laid the foundation for the rethinking of architectural form in a way that gives freedom to express and the audacity to venture.

Gaudi turned the most advanced style of his era, the Gothic, into the seed for research that would enable him to arrive at the definition of his own structural system, with equilibrated arches and without buttresses, a system that made it possible to build works as complex as the Church of Colònia Güell and the Church of the Sagrada Família (Giralt-Miracle 2012).6

From Gaudi’s fluid naturalistic oration of form and space to the most recent angular interpretation of both vegetal and human form as created by sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs, the Sagrada carries on a character that is second to none. And while I am on a hunt for ornamentation on religious buildings, I can say without fear of ridicule that more than an ornamented building, Sagrada Família is a peculiar ornament unto itself.

Fig. 20: The betrayal with a kiss. Neomodern angular style sculpture at the passion façade. Work by Josep Maria Subirachs.

Fig. 21: Angular style sculpture at the passion façade, western end of the Sagrada Família. Work by Josep Maria Subirachs.

Fig. 22: Jesus, presented to the crowd by Pontus Pilate. Crucify Him they shouted! Crucify Him! Sculptural piece at the passion façade, western end of the Sagrada Família. Work by Josep Maria Subirachs.

Fig. 23: Another of the sculptures at the passion façade, western end of the Sagrada Família. Work by Josep Maria Subirachs.

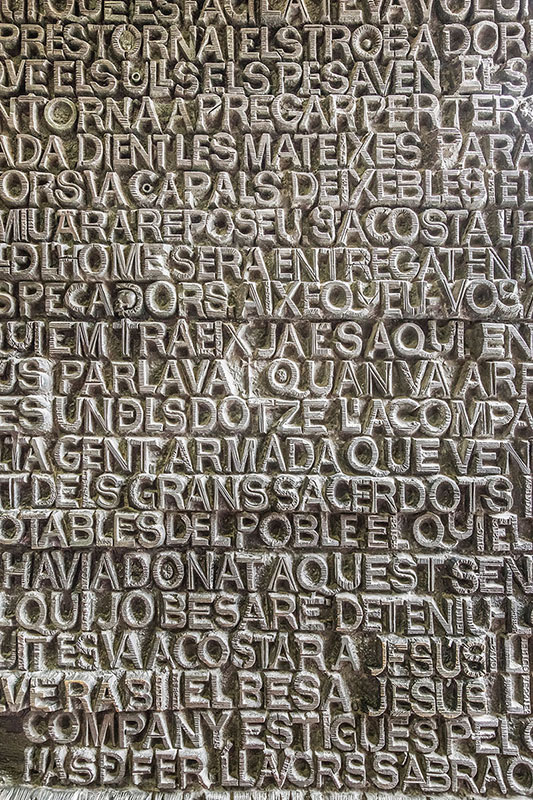

Fig. 24: Textual relief sculpture on the door of the western Passion façade.

Fig. 25: The top area of the Sacristy at Sagrada Família.

Fig. 26: A close up detail of the stone work on the eastern end just short of the Nativity sculptural works. Sagrada Família.

Fig. 27: A view showing part of the Sagrada Família School.

Fig. 28: A close up of part of the Sagrada Família School.

Fig. 29: A beautifully crafted minimalist style marble lectern. On it, the wrods Paraula de Due, which is Catalan for "Word of God."

A Note on Girona

Moving further north of Barcelona to a place called Girona, I am drawn to visit a site that has made quite a reputation for itself. Being a Game of Thrones fan, I had promised myself to visit the Cathedral of Saint Mary of Girona. The famous church perches carefully atop a hill and it is the site used for the Game of Thrones season six set for the Sept of Baelor in King’s Landing.

One is confronted by a beautiful 17th-century Baroque façade on the western end as you make your way up the 90 grand steps. Though the excellent Baroque sculptures that adorn the western façade are of very recent manufacture by a local artist in the 1960s, the grand steps are indeed from the 17th century and have been a very prominent feature of the cathedral. The stairs hit the lime light when they were featured in the popular TV series Game of Thrones. In season six, Jamie Lannister, a frontal figure and character in the medieval themed series, is seen charging up the elegant stairs on horseback in a scene where he tries to stop a so-called walk of atonement of Queen Margaery—another key character. The Girona Cathedral’s great stairs are also featured prominently in a Guinness Book of Records attempt by two Vietnamese brothers who were acrobats. They went on to break the world record for the most consecutive stairs climbed while balancing a person on the head. It took the duo less than a minute to make it to the top of the flights of 90 steps.

Fig. 30: Girona Cathedral from a nearby elevated point.

Fig. 31: A view of the Girona Cathedral main western façade and grand Baroque style staircase.

Fig. 32: The great stairs on the western end of the Girona Cathedral. The 17th-century 90-step stairway has become a popular site for TV and showbiz features.

Fig. 33: the beautiful Baroque façade on the western end of Girona Cathedral.

Fig. 34: Details of the sculptural ornamentation of the western façade of the Girona Cathedral.

Fig. 35: A view of Girona Cathedral from a nearby elevated point showing the cathedral tower and the beautiful landscape beyond the cathedral.

Fig. 36: A close up exterior view of the apse of Girona Cathedral.

Fig. 37: The eastern end of the Girona Cathedral.

The Girona church is a Roman Catholic cathedral that started circa 1015 and has gone through several stylistic changes over the years from Romanesque to Gothic and later Baroque. The cathedral boasts of the widest nave (Gothic) in the world at about 75 ft (23 m), second only to the nave of St Peter’s Basilica. One will quickly notice something about the breadth of the nave—it does appear truly wider than most I have seen. The apse is blocked off by a wall, hence one is required to pass through the ambulatory to catch a glimpse of the altarpiece.

The interior of the Girona Cathedral is largely bare, carrying on the character of its Romanesque past. The vaults and walls are bare, but the cathedral treasury is anything but bare. It is loaded with fine examples of altarpieces, tapestry, and gold-covered pieces.

The church bell tower, known as the Charlemagne, is the only surviving of two towers. The tower is prominent and gives character to the otherwise rigid structure. The cathedral’s Romanesque cloister to its northern side is a prominent and typical feature of the Romanesque style. The cloister features a series of double columns with deeply ornamented capitals. These columns support a thick wall that runs through the length of the cathedral on the northern side.

Fig. 38: Inside the nave of the Girona Cathedral.

Fig. 39: A view from the aisles looking towards the east showing parts of the altar and apse.

Fig. 40: The Rose window on the wall that separates the choir area from the rest of the nave.

Fig. 41: A view from the nave looking towards the altar and apse.

Fig. 42: An ornamented altar canopy piece.

Fig. 43: One of the altar pieces in the chapels to the northern end of the cathedral.

Fig. 44: A stained glass window in Girona Cathedral.

Fig. 45: A view of the cloister of Girona Cathedral. The courtyard is seen here through two columns.

Fig. 46: A view of the Tympanum at the southern end of the cathedral.

Fig. 47: Archway that leads into the cathedral grounds.

Fig. 48: A shot of the Eiffel Bridge that gives access to the cathedral area over the Onyar River.

Fig. 49: Residential apartments near the cathedral grounds. The Onyar River in the foreground.

Fig. 50: Residential apartments occlude the Girona Cathedral. The Onyar River in the foreground.

The town of Girona is peaceful and unassuming. The people are mostly not inquisitive, going past you without a second look or care. The Onyar River is a major feature and it forms an important part of the city's character. The people of Girona, like those in Barcelona, appear to be collectively united on one purpose—a free Catalonia. I saw several flags of the yellow and red stripes hanging from residential apartment balustrades, shop windows, and street corners. It is a type of mellow protest that is a little unsettling. All the political tension aside, Girona is generally a good place to reflect. I, however, must go south now to the central Spanish cities to see and learn more. My stay here was short but rich.

1 David Mower, Gaudí, (Oresko Books Limited, 1977), 6

2 Rainer Zerbst, Gaudí – A Life Devoted to Architecture (Taschen, 1985), 190–215

3 Patricia Blessing, "Spanish itineraries, Part 1: Barcelona to Ronda." Accessed November 2, 2017.

4 Jordi Fauli. The basilica of the Sagrada Família (P&M Ediciones, 2016)

5 Ibid.

6 Giralt-Miracle Daniel. Gaudi: Nature of Architecture. Accessed November 10, 2017.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top