-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The prestigious H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship allows a recent graduate or emerging scholar to study by travel for one year while observing, reading, writing, or sketching. Fellowship recipients are required to document their travels through monthly posts on the SAH Blog.

2025 Amalie Elfallah

2025 Francesca Sisci

2024 Michele Tenzon

2024 Stathis G. Yeros

2023 Jasper Ludewig

2023 Annie Schentag

2022 Anne Delano Steinert

2022 Adil Mansure

2019 Sundus Al-Bayati

2018 Aymar Mariño-Maza

2018 Zachary J. Violette

2017 Sarah Rovang

2016 Adeyemi Akande

2015 Danielle S. Willkens

2014 Patricia Blessing

2013 Amber N. Wiley

2025 Recipients

Architecture, Agriculture, and What Was Left Behind

Nov 13, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this fourth installment of his travel blog, he reflects on his travels and makes a case for studying the 'minor narratives' that appear when we read architecture as a manifestation of power dynamics. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo"

Part Two: "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future"

Part Three: "One-crop country: Agricultural and Trading Heritage in Gambia"

__________________________________________________________________

It might be slightly unusual, but not unique1, to discuss agriculture, or agribusiness, within the context of architecture. There is no doubt —and I've reflected on this a lot over the past months—that the challenge I set for myself,

which the Society of Architectural Historians trusted me to undertake, stems from a personal obsession to seek architecture beyond itself, in the relationships it establishes with other disciplines and in contexts that might seem less than obvious.

More than once, when explaining the purpose of my journey, I noticed a hint of confusion in my listeners. Perhaps because of my own muddled explanations. What could palm oil and groundnuts possibly have to say to someone interested in architectural

history?

This always required an additional layer of explanation, connecting these to objects more familiar to the discipline’s traditional image: company towns, industrial complexes, markets, ports, and infrastructure. Yet, it remained a challenge to convince

people that, despite my ignorance of botany, agronomy, or industrial engineering, I am genuinely interested in the processes involved in palm oil extraction, in the life cycle of a plantation, or in groundnut storage. An interest driven by a naïve

enthusiasm—perhaps like that of an amateur who constantly rediscovers the obvious with amazement.

And yet, the pervasive influence of food production and consumption chains has implications for our built environment. They shape not only rural landscapes but also urban infrastructures. They extend their reach into nearly every aspect of daily life—impacting

logistics, transportation networks, and even housing. Production and consumption chains, as they unfold across time and geography, become a network linking locales that may appear remote to the Western eye with major industrial and port centers on

national, continental, and global scales.

Through this web, distant agricultural zones and small-scale production sites are integrated into vast supply chains, feeding into the rhythms of industrial powerhouses and trade hubs. Agribusiness creates a spatial continuity that binds seemingly disparate

regions into a shared, though uneven, economic landscape. The architecture and infrastructure that emerge from this dynamic shape a world where rural outposts and urban centers are interdependent, reflecting the economic forces that connect them across

vast distances.

Physically visiting these places means experiencing this connection firsthand. It reveals the tangible presence of this vast network. It also powerfully highlights the extraordinary contrast between globalization’s promises of progress and the deeply

rooted realities on the ground. Despite the narrative of development and opportunity that globalization professes, the entrenched practices of extraction and labor exploitation reveal an uneven exchange, one that continues to shape the built environment,

social structures, and local realities of these regions.

Defunct plantations, leaving the communities that once gathered around them even more abandoned, revive patterns deeply rooted in centuries of history. Monumental—and failed—projects aimed at social and economic transformation in rural areas

reflect the inherent violence of ideology, often regardless of its orientation, or the subtler violence masked by the seemingly neutral hegemony of technical knowledge. These sites tell stories of abandoned promises and disrupted livelihoods, where

aspirations for progress clash with the realities on the ground, creating landscapes marked by both ambition and neglect.

These models, which for centuries has aligned with the colonial exploitation of natural resources and, more often than not, the brutal subjugation of local populations, survived, and often thrived throughout decolonization and persists in various forms

today. In these encounters, the structural inequalities embedded within the global agribusiness chains become vividly apparent, underscoring a legacy that remains woven into the fabric of rural economies and landscapes.

In this sense, if we believe in architecture’s role to materialize power dynamics—relationships that are both tangible and measurable within the collective imagination, accumulated cultural material, and its narratives—then palm oil and groundnuts become as relevant as cement and steel. They shape landscapes and communities just as decisively, embodying a physical manifestation of economic and social forces that architecture has the potential to reveal.

Fig. 1: A coffee plant nursery in Yangambi

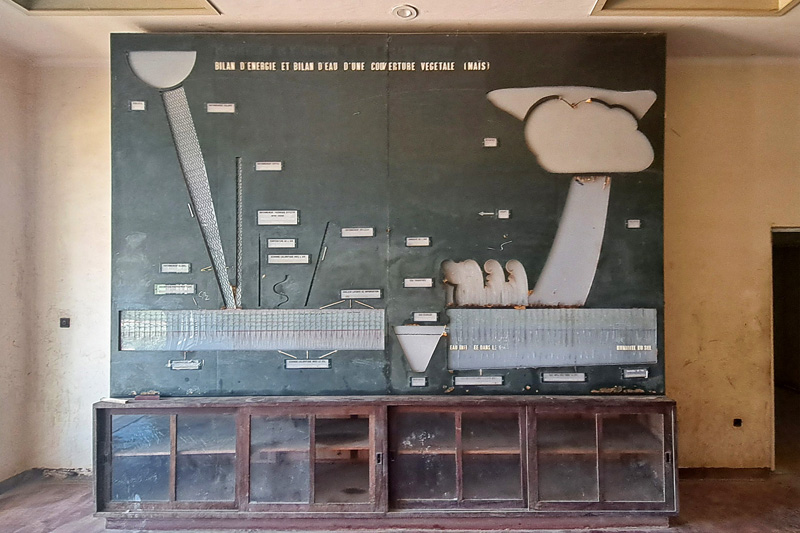

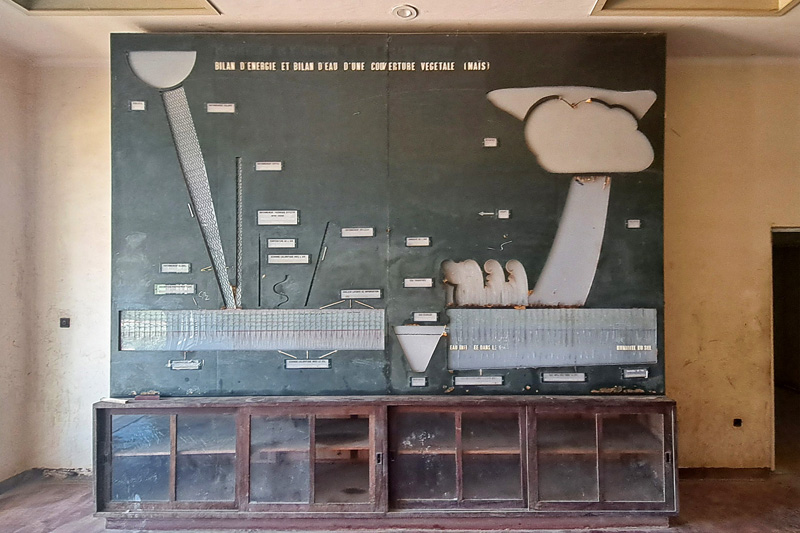

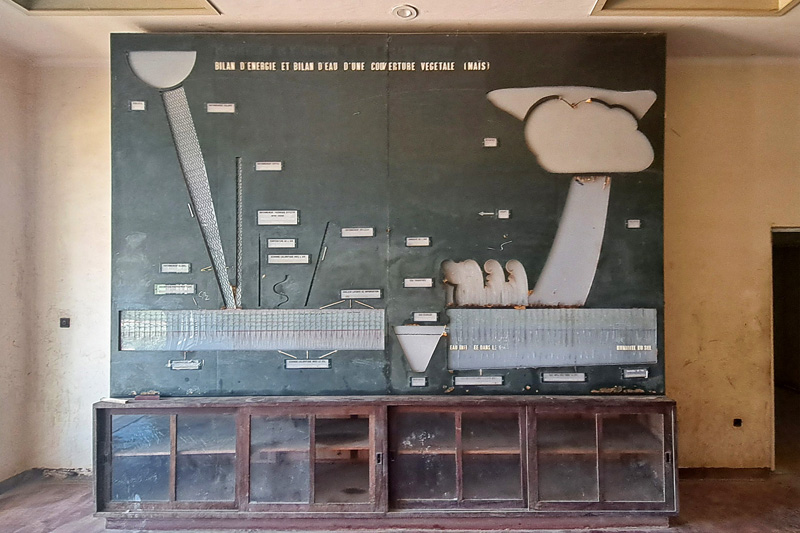

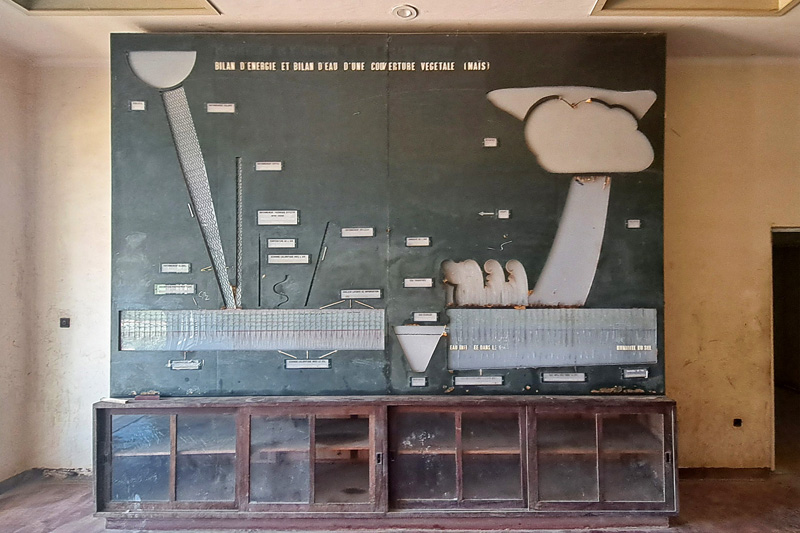

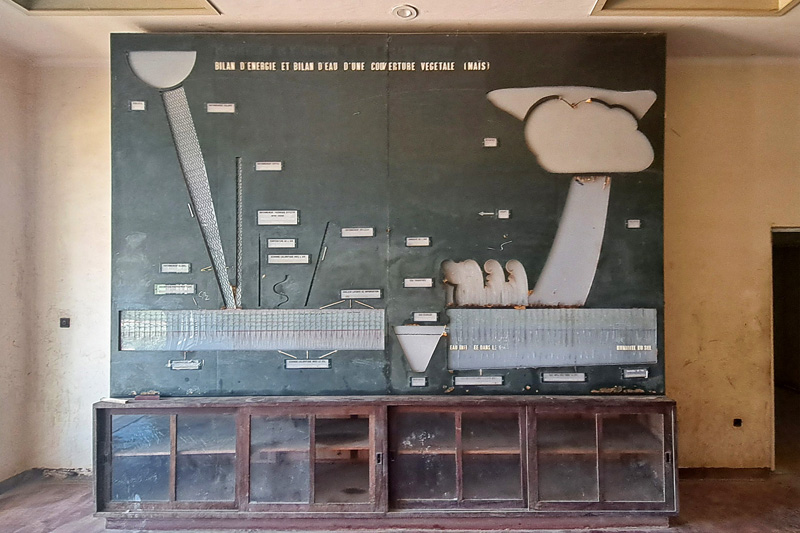

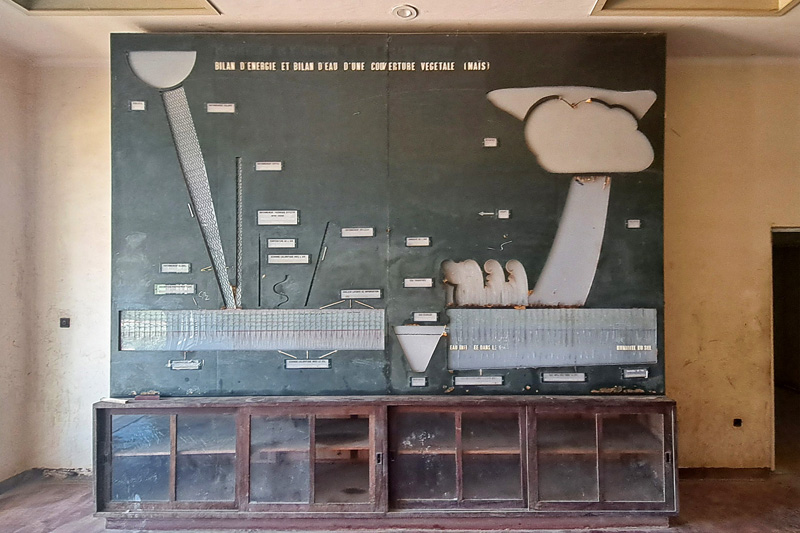

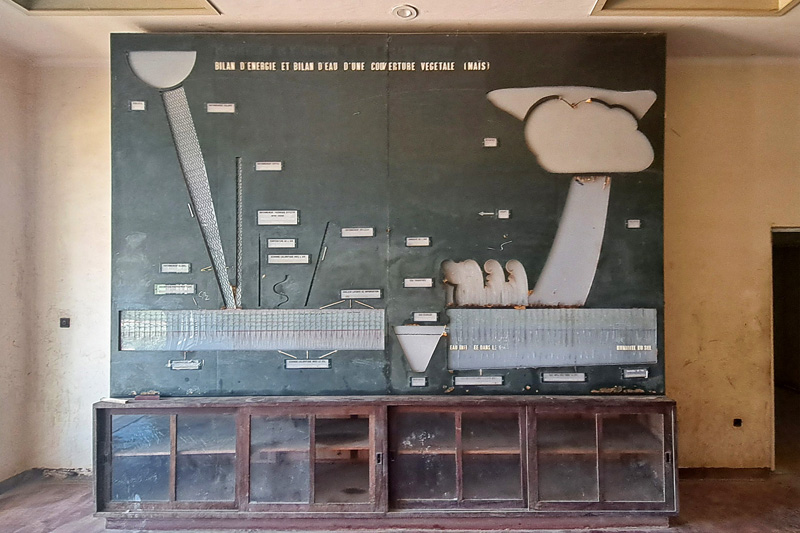

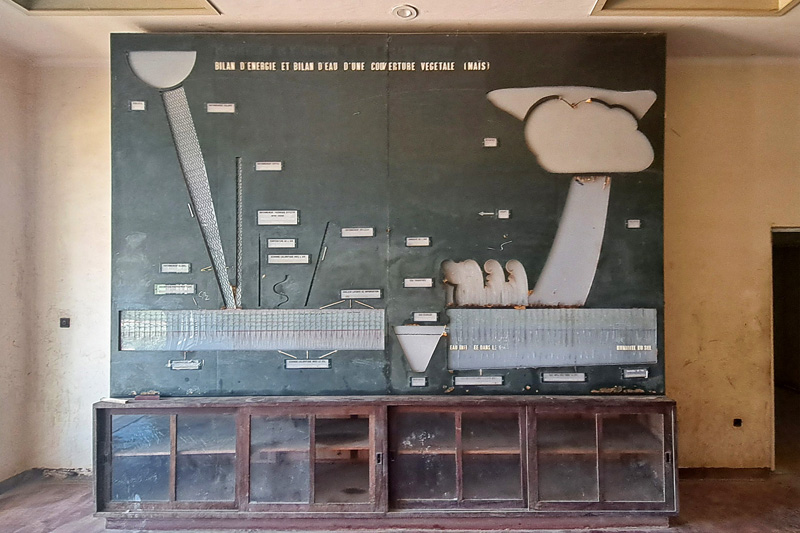

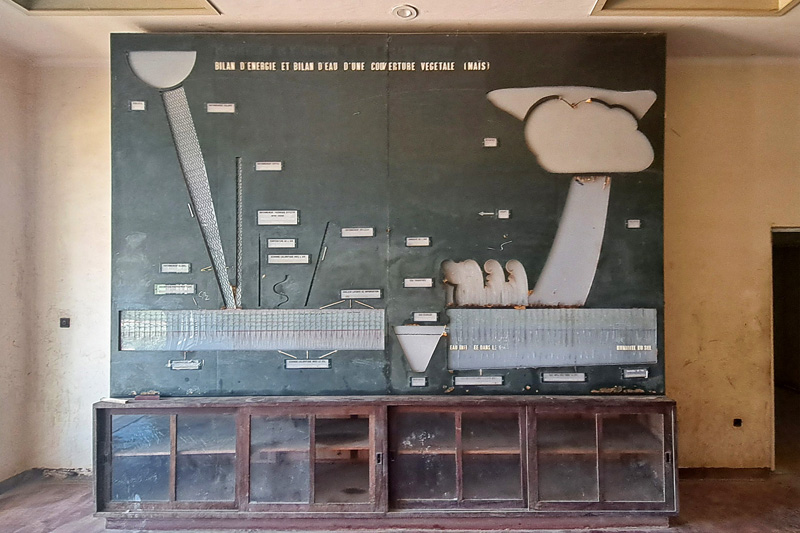

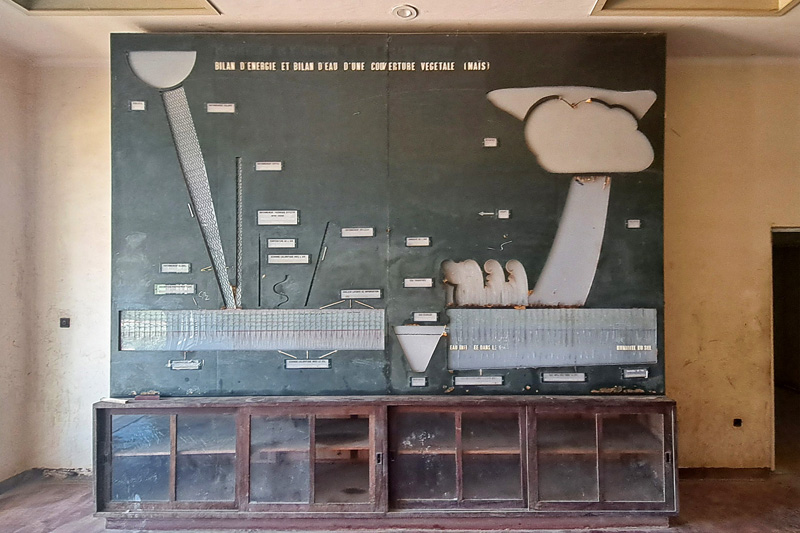

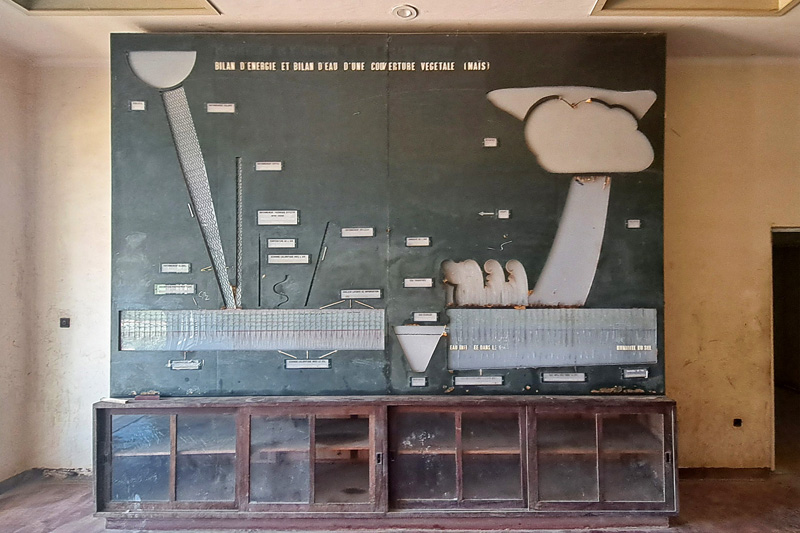

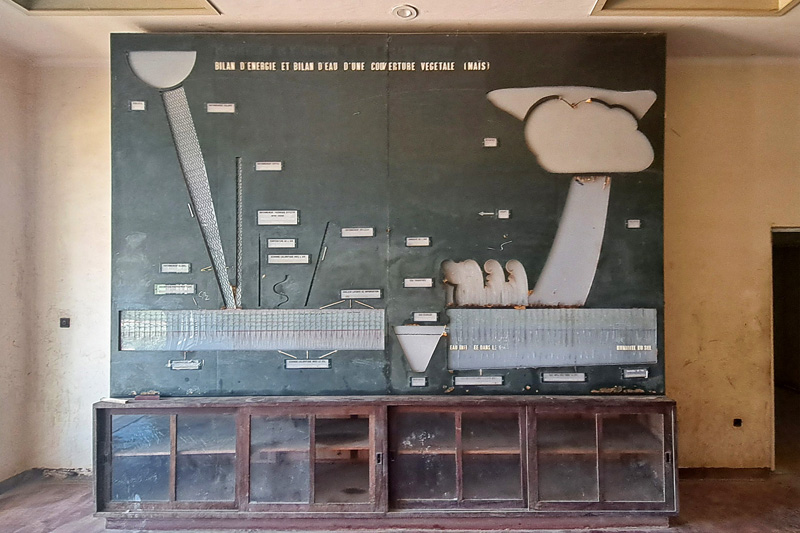

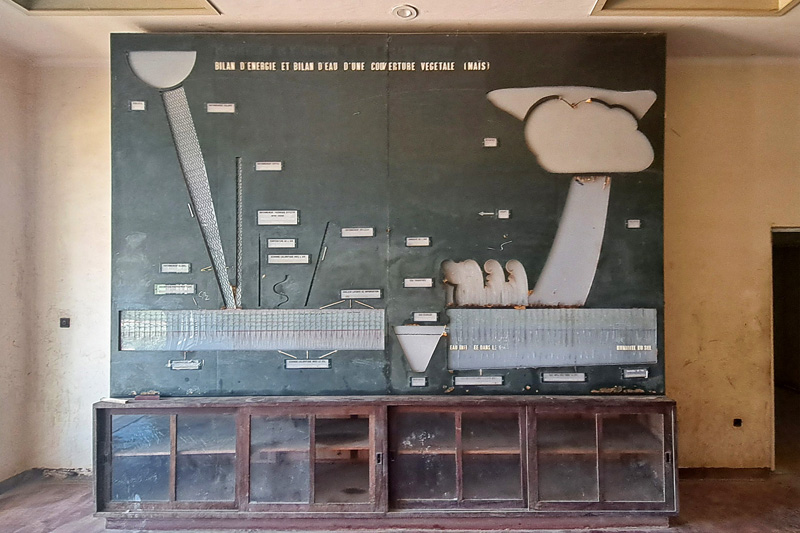

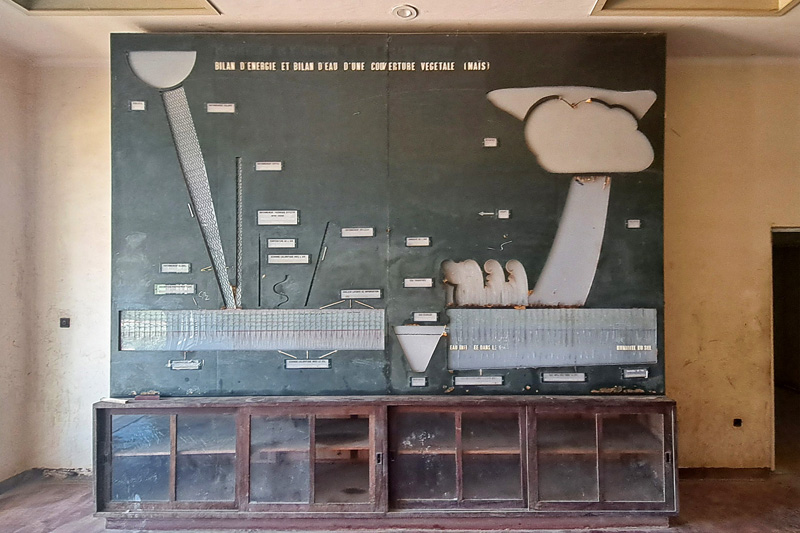

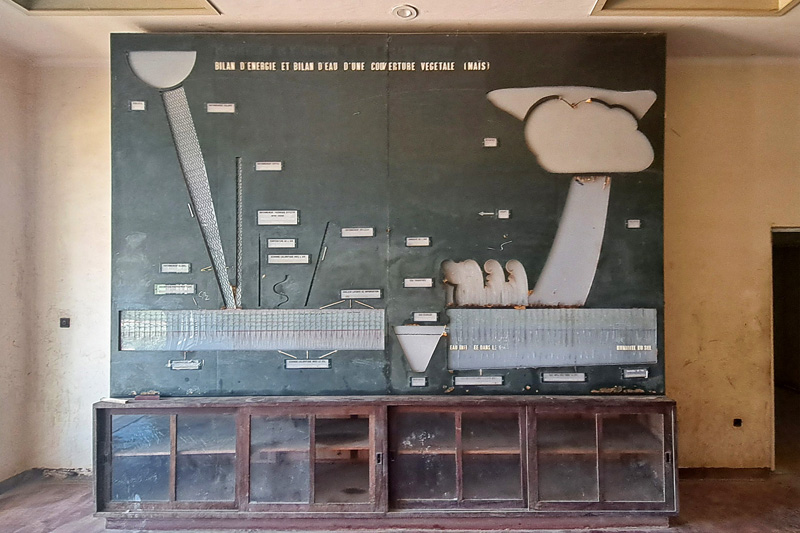

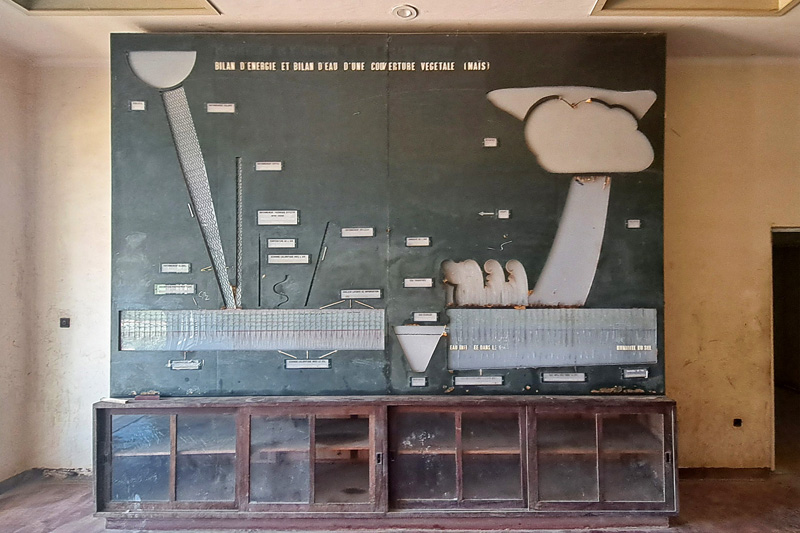

Fig. 2; 3: A backlit panel illustrating the absorption and evaporation cycle for maize cultivation. INERA.

Much of what I saw and learned has been left out of the notes published here—partly for narrative coherence, partly because I couldn’t find a compelling way to present it, and partly because I wanted to spare the reader the tedium of details

and episodes that seemed more relevant to me personally than to others. Some traces of this journey can also be found in the SAHARA image platform, still too sparse on content from the African continent, to which I’ve made a modest contribution.

Among the architectural artifacts that didn’t make it into my previous travel notes, but to which I’ve become somewhat attached, are a few of Kinshasa’s landmarks: the RTNC tower, which I was able to visit after some bureaucratic hurdles

and the help of many; my favorite monument, the Limete Tower; as well as the SOZACOM tower and the CCIZ building (now the Fleuve Congo Hotel). Other sites include the UniKin campus, Karume’s Zanzibar New Town, the university campus and the old

port in Dar es Salaam.

Thanks to the flexibility granted by the SAH in managing the travel schedule, I was able to enrich my journey with additional experiences, which allowed me to extend my stay in Kinshasa by a few weeks and gain a more tangible sense of the city. Among the most vivid memories are those from the artist residency and the small exhibition organized in collaboration with friends at Laboratoire Kontempo and Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, co-funded by the University of Liverpool. These experiences stand out not only for the memories they left behind but also, perhaps especially, for the challenges we encountered along the way, which didn’t prevent us from achieving even more than we had anticipated.

Fig. 4; 5: The Congolese National Radio and Television building. View of the entrance and the entrance lobby.

Fig. 6: Merdi Tusumba Eduard and Anli Lukunku during the art residency at the Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, working on a model of Kinshasa as a tool to rethink the city's urban past and imagine its future. Learn more.

Fig. 7: My favorite monument, the Limete 'Interchange' Tower in Kinshasa, photographed as it should be, while speeding down the surrounding avenues.

During these months, I discovered and re-discovered an interest in rivers, failures, and minor narratives, and some traces of this can be found, more or less explicitly, in my published notes. Beyond a primordial fascination with rivers like the Congo

and the Gambia—which, not coincidentally, name two of the countries I visited—they emerged from my travels as powerful forces shaping settlement patterns, economic development, and even social hierarchies. Even the most superficial history

of Sub-Saharan Africa reveals how rivers like the Niger, Congo, Senegal, Volta, and Gambia have not only shaped the layout and development of cities and settlements but have also deeply influenced their architectural identity and the socio-political

and economic conditions underlying their urban histories. I aim to continue investigating their underexplored heritage and lasting influence on the built environment and the way it is perceived and lived in my new academic ‘adventure’

at TU Delft.

The history and current state of rural development in Africa is filled with grand ambitions and extraordinary promises. If, as I believe, the role of the historian is to deconstruct these narratives, it is just as relevant to examine how they have failed

and sometimes left little trace as it is to address the significant impacts of the 'successful' ones. Initiatives like Tanzania's Groundnut Scheme and the Ujamaa villagization program show how ambitious, top-down interventions can shape spatial organization

and reveal the consequences of overlooking local contexts. Alongside the classics of political, historical, and anthropological literature on this topic, I would credit Adam Guerin, whose essay on the Gharb Valley in Morocco2 first

introduced me to the value of this perspective and is something I wish I had explored further in my doctoral research.

In a way, this led me to question how to give voice and strength to minor narratives, and my journey to Gambia was crucial in this. They provide an invaluable lens for uncovering the richness and complexity of cultural landscapes. Stories of economic practices, displacement, and adaptation—often overshadowed by dominant historical accounts—can reveal alternative histories and nuanced identities. Embracing these minor narratives within architectural research has the potential to contribute to more inclusive, contextually relevant, and culturally enriched built environments. The question of how effectively these can be addressed in a discipline like ours, which easily succumbs to the allure of the grand and the oversized, remains open for me.

Fig. 8; 9: The view from some of the places I've stayed at over the past few months.

Apart from all the challenges of traveling through unfamiliar and not always easily accessible places, one of the hardest tasks has been to convey this experience without omitting its ambiguities and emotional aspects, while simultaneously doing my best

to avoid falling into the many clichés of exotic travel literature, especially those often applied to Africa: overcrowded cities, heavy traffic, untouched nature, and unsettling economic divides. Above all, I made every effort to avoid aestheticizing

poverty while also not ignoring its existence. Like any experience, this one is refracted through my own preconceptions, habits, and the cultures of my home countries. I hope, at least in part, to have avoided presenting a distorted image of the places

I visited and the stories shared with me.

The most interesting aspects of this experiences have been possible solely thanks to the people I have met during these months. Some of them were old friends, while others may become so. I thank them for their generosity. There have also been conflicts

and disappointments, more in the background than during these months of travel. I don’t want to come across as overly sentimental, but I have learned from these experiences as well.

I’m bringing home many vivid memories and a curiosity about many stories that I could only get to know superficially. Among the goals I set for myself and those who funded me, there was no specific research output. Alas, I didn't have any revolutionary methodological insights. However, I experimented with ways of writing about my work that are unusual for me, I read and saw a lot. That already feels like quite a lot to me.

Fig. 10; 11: Abandoned factory and company housing

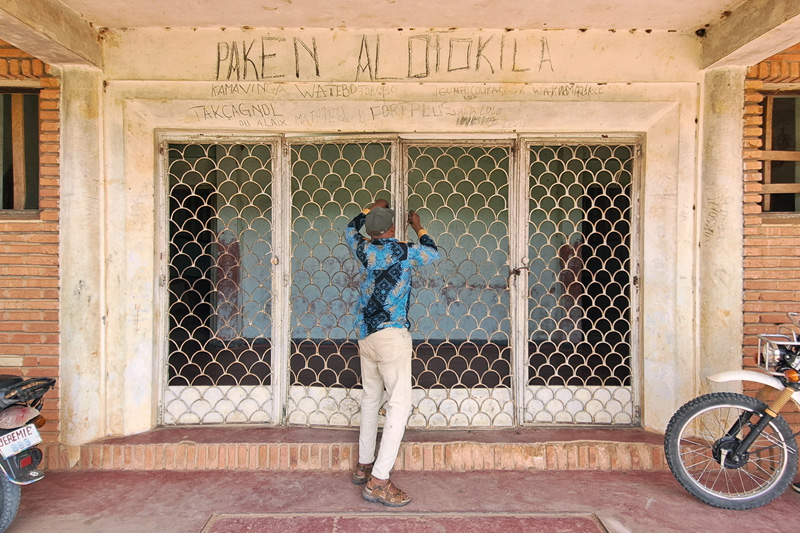

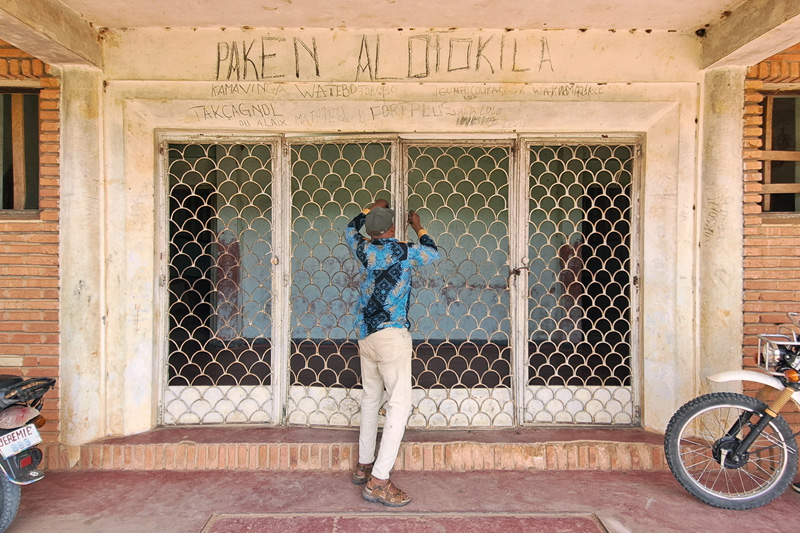

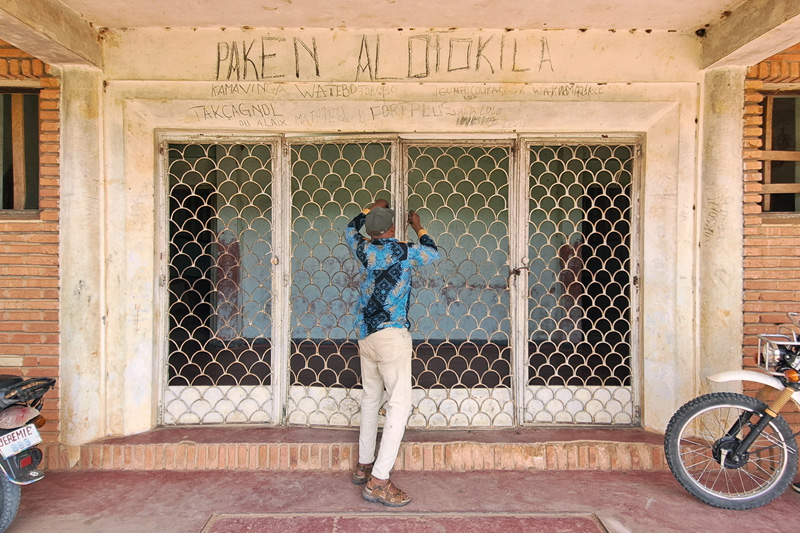

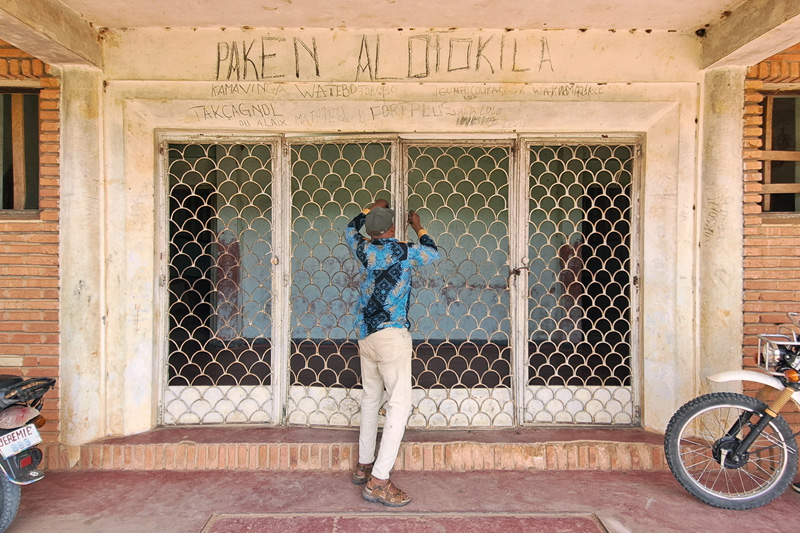

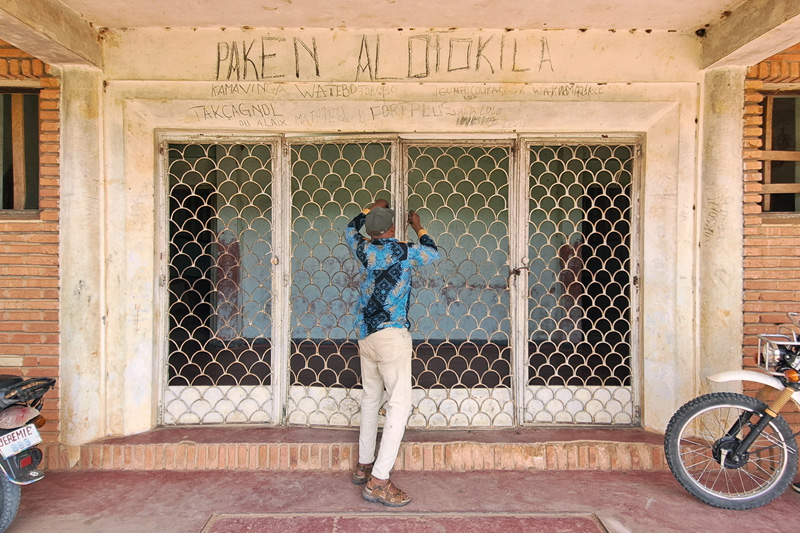

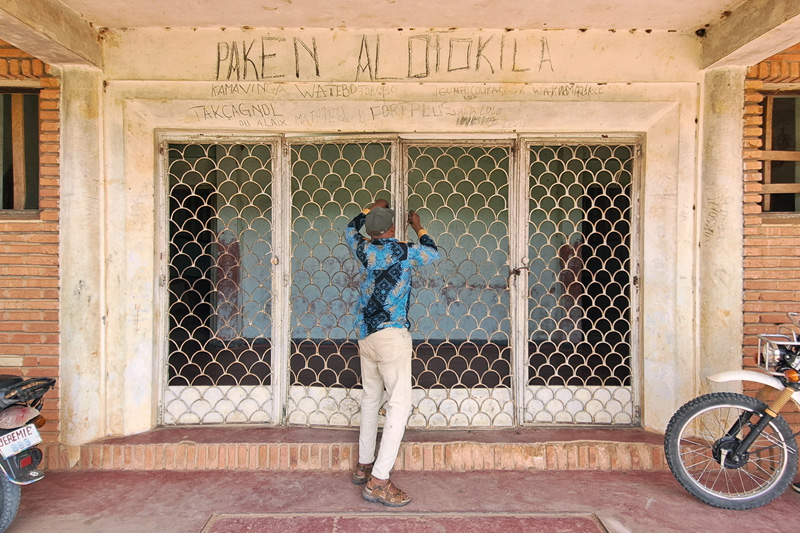

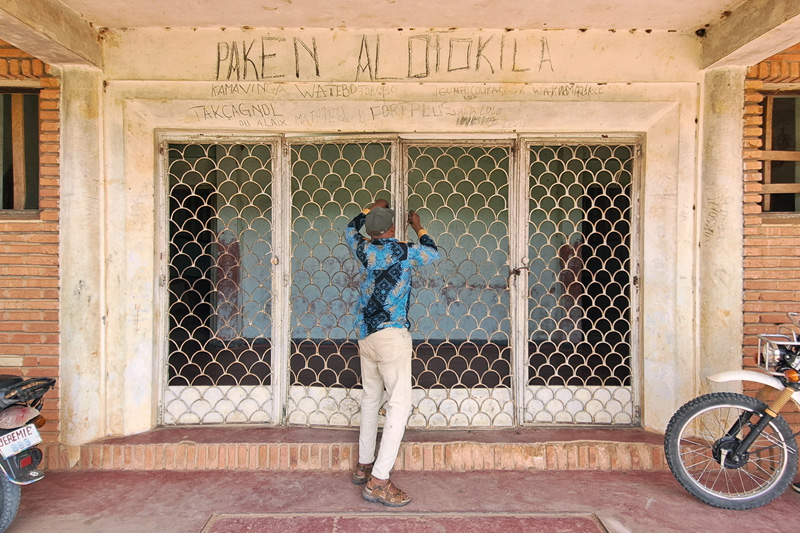

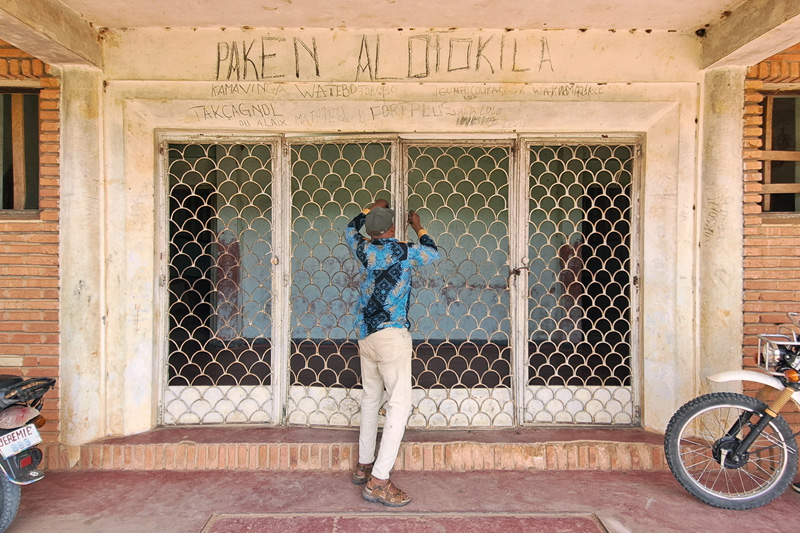

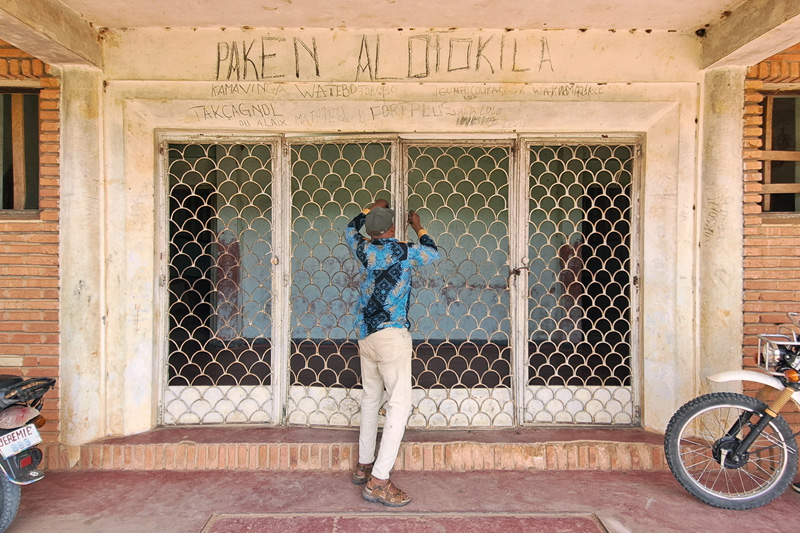

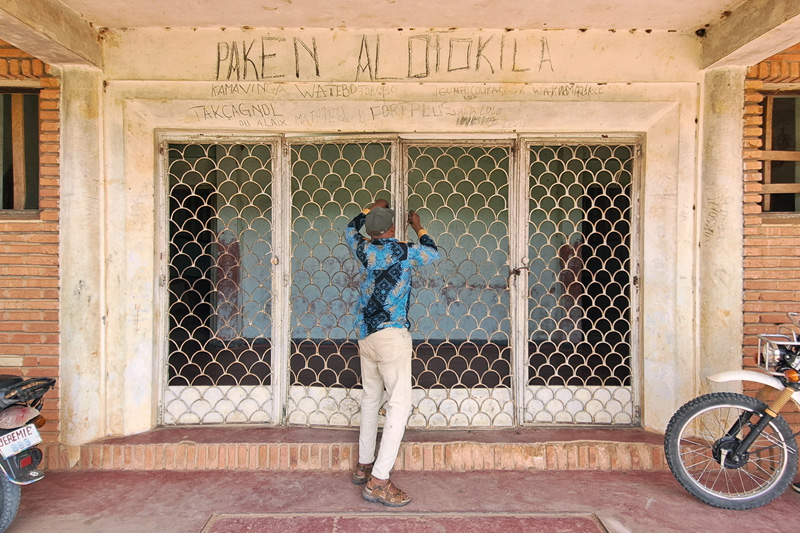

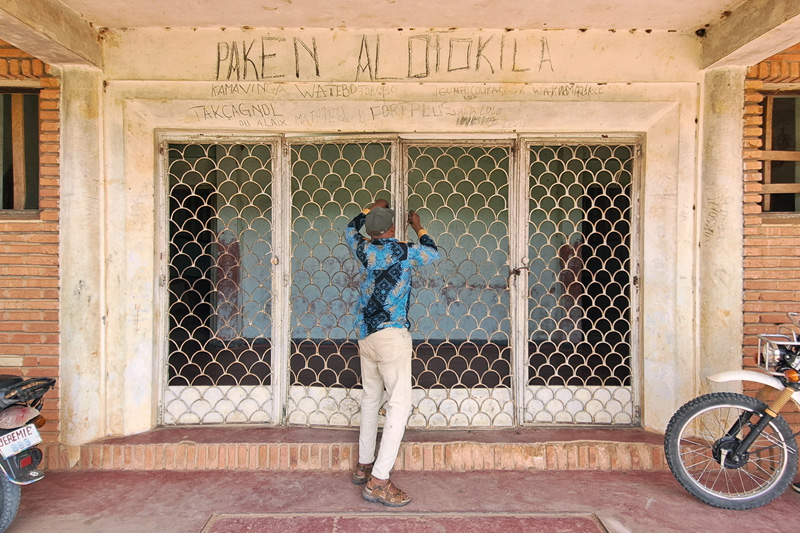

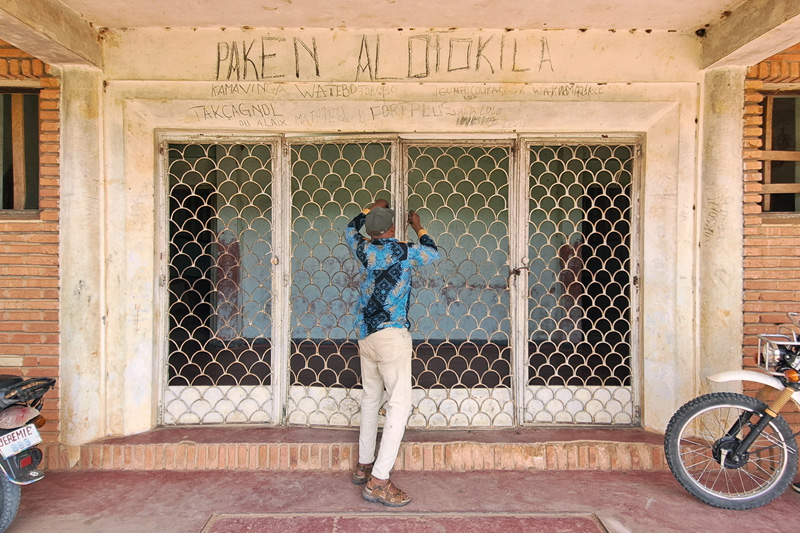

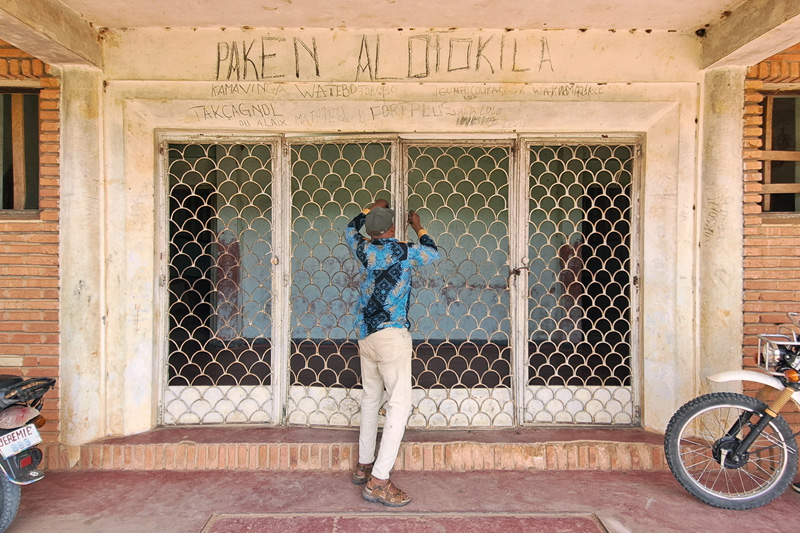

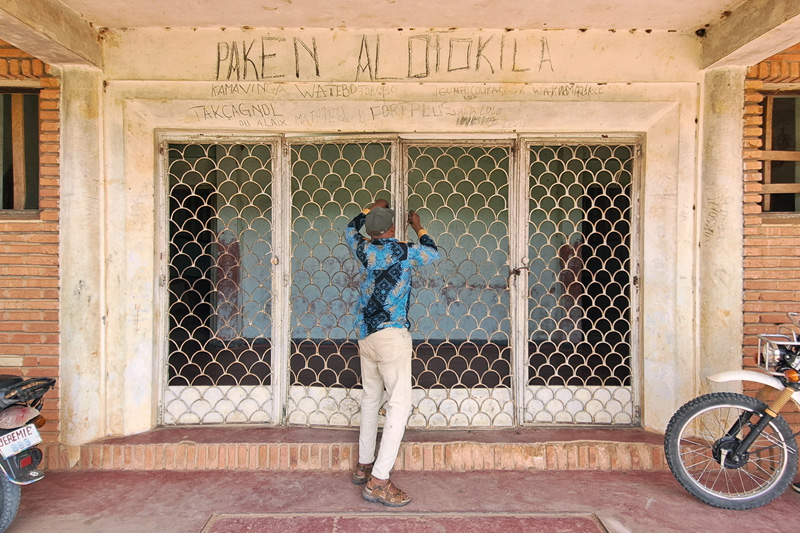

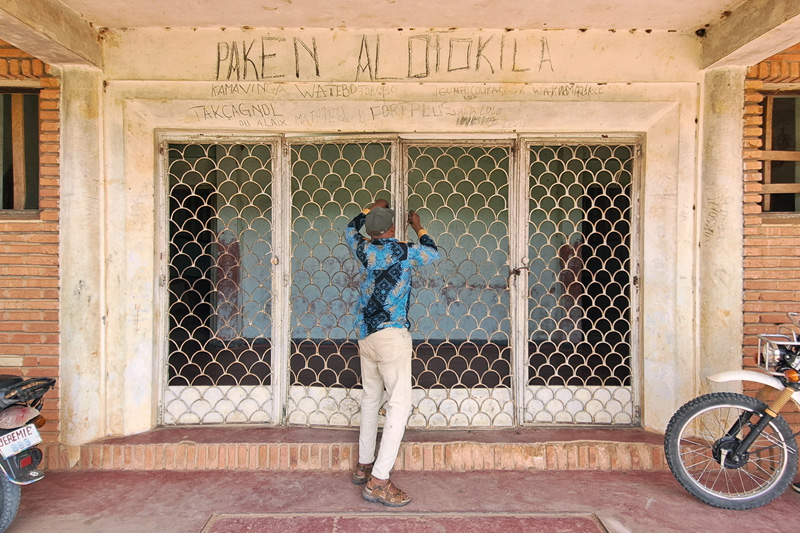

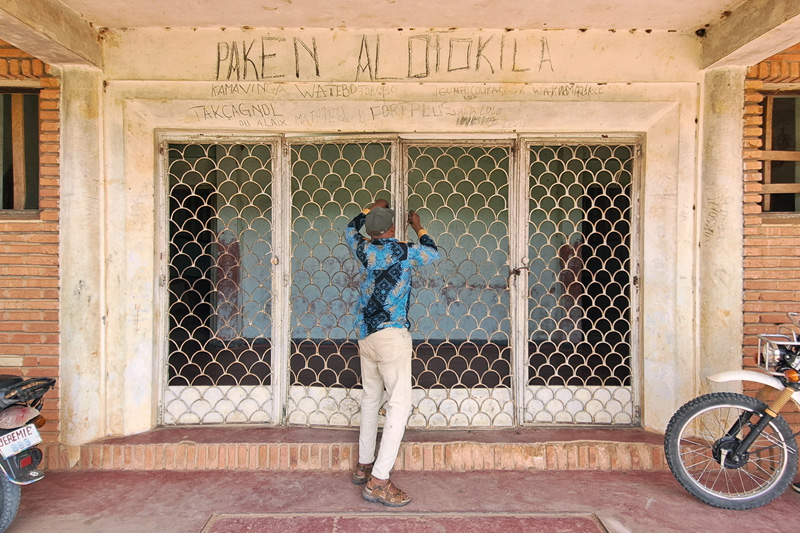

Fig. 12: The custodian of the former INERA staff social club closes the theater doors behind us.

-----------------------------------

[1] To mention just a few recent references, among many, that have influenced me in drafting these notes: Jasper Ludewig’s work as part of this same fellowship on the impact of fertilizers, Will Davis’s ongoing research on “Plantation

Architectures,” and the project that initially sparked my interest, in which I participated, soon to publish its summary volume: Fisher, A., et al., *Modernist Reinventions of the Rural Landscapes*, Routledge.

[2] Adam Guerin (2016) “Disaster Ecologies: Land, Peoples, and the Colonial Modern in the Gharb, Morocco, 1911-1936”, Journal of Social and Economic Studies of the Orient, 59:3.

Architecture, Agriculture, and What Was Left Behind

Nov 13, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this fourth installment of his travel blog, he reflects on his travels and makes a case for studying the 'minor narratives' that appear when we read architecture as a manifestation of power dynamics. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo"

Part Two: "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future"

Part Three: "One-crop country: Agricultural and Trading Heritage in Gambia"

__________________________________________________________________

It might be slightly unusual, but not unique1, to discuss agriculture, or agribusiness, within the context of architecture. There is no doubt —and I've reflected on this a lot over the past months—that the challenge I set for myself,

which the Society of Architectural Historians trusted me to undertake, stems from a personal obsession to seek architecture beyond itself, in the relationships it establishes with other disciplines and in contexts that might seem less than obvious.

More than once, when explaining the purpose of my journey, I noticed a hint of confusion in my listeners. Perhaps because of my own muddled explanations. What could palm oil and groundnuts possibly have to say to someone interested in architectural

history?

This always required an additional layer of explanation, connecting these to objects more familiar to the discipline’s traditional image: company towns, industrial complexes, markets, ports, and infrastructure. Yet, it remained a challenge to convince

people that, despite my ignorance of botany, agronomy, or industrial engineering, I am genuinely interested in the processes involved in palm oil extraction, in the life cycle of a plantation, or in groundnut storage. An interest driven by a naïve

enthusiasm—perhaps like that of an amateur who constantly rediscovers the obvious with amazement.

And yet, the pervasive influence of food production and consumption chains has implications for our built environment. They shape not only rural landscapes but also urban infrastructures. They extend their reach into nearly every aspect of daily life—impacting

logistics, transportation networks, and even housing. Production and consumption chains, as they unfold across time and geography, become a network linking locales that may appear remote to the Western eye with major industrial and port centers on

national, continental, and global scales.

Through this web, distant agricultural zones and small-scale production sites are integrated into vast supply chains, feeding into the rhythms of industrial powerhouses and trade hubs. Agribusiness creates a spatial continuity that binds seemingly disparate

regions into a shared, though uneven, economic landscape. The architecture and infrastructure that emerge from this dynamic shape a world where rural outposts and urban centers are interdependent, reflecting the economic forces that connect them across

vast distances.

Physically visiting these places means experiencing this connection firsthand. It reveals the tangible presence of this vast network. It also powerfully highlights the extraordinary contrast between globalization’s promises of progress and the deeply

rooted realities on the ground. Despite the narrative of development and opportunity that globalization professes, the entrenched practices of extraction and labor exploitation reveal an uneven exchange, one that continues to shape the built environment,

social structures, and local realities of these regions.

Defunct plantations, leaving the communities that once gathered around them even more abandoned, revive patterns deeply rooted in centuries of history. Monumental—and failed—projects aimed at social and economic transformation in rural areas

reflect the inherent violence of ideology, often regardless of its orientation, or the subtler violence masked by the seemingly neutral hegemony of technical knowledge. These sites tell stories of abandoned promises and disrupted livelihoods, where

aspirations for progress clash with the realities on the ground, creating landscapes marked by both ambition and neglect.

These models, which for centuries has aligned with the colonial exploitation of natural resources and, more often than not, the brutal subjugation of local populations, survived, and often thrived throughout decolonization and persists in various forms

today. In these encounters, the structural inequalities embedded within the global agribusiness chains become vividly apparent, underscoring a legacy that remains woven into the fabric of rural economies and landscapes.

In this sense, if we believe in architecture’s role to materialize power dynamics—relationships that are both tangible and measurable within the collective imagination, accumulated cultural material, and its narratives—then palm oil and groundnuts become as relevant as cement and steel. They shape landscapes and communities just as decisively, embodying a physical manifestation of economic and social forces that architecture has the potential to reveal.

Fig. 1: A coffee plant nursery in Yangambi

Fig. 2; 3: A backlit panel illustrating the absorption and evaporation cycle for maize cultivation. INERA.

Much of what I saw and learned has been left out of the notes published here—partly for narrative coherence, partly because I couldn’t find a compelling way to present it, and partly because I wanted to spare the reader the tedium of details

and episodes that seemed more relevant to me personally than to others. Some traces of this journey can also be found in the SAHARA image platform, still too sparse on content from the African continent, to which I’ve made a modest contribution.

Among the architectural artifacts that didn’t make it into my previous travel notes, but to which I’ve become somewhat attached, are a few of Kinshasa’s landmarks: the RTNC tower, which I was able to visit after some bureaucratic hurdles

and the help of many; my favorite monument, the Limete Tower; as well as the SOZACOM tower and the CCIZ building (now the Fleuve Congo Hotel). Other sites include the UniKin campus, Karume’s Zanzibar New Town, the university campus and the old

port in Dar es Salaam.

Thanks to the flexibility granted by the SAH in managing the travel schedule, I was able to enrich my journey with additional experiences, which allowed me to extend my stay in Kinshasa by a few weeks and gain a more tangible sense of the city. Among the most vivid memories are those from the artist residency and the small exhibition organized in collaboration with friends at Laboratoire Kontempo and Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, co-funded by the University of Liverpool. These experiences stand out not only for the memories they left behind but also, perhaps especially, for the challenges we encountered along the way, which didn’t prevent us from achieving even more than we had anticipated.

Fig. 4; 5: The Congolese National Radio and Television building. View of the entrance and the entrance lobby.

Fig. 6: Merdi Tusumba Eduard and Anli Lukunku during the art residency at the Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, working on a model of Kinshasa as a tool to rethink the city's urban past and imagine its future. Learn more.

Fig. 7: My favorite monument, the Limete 'Interchange' Tower in Kinshasa, photographed as it should be, while speeding down the surrounding avenues.

During these months, I discovered and re-discovered an interest in rivers, failures, and minor narratives, and some traces of this can be found, more or less explicitly, in my published notes. Beyond a primordial fascination with rivers like the Congo

and the Gambia—which, not coincidentally, name two of the countries I visited—they emerged from my travels as powerful forces shaping settlement patterns, economic development, and even social hierarchies. Even the most superficial history

of Sub-Saharan Africa reveals how rivers like the Niger, Congo, Senegal, Volta, and Gambia have not only shaped the layout and development of cities and settlements but have also deeply influenced their architectural identity and the socio-political

and economic conditions underlying their urban histories. I aim to continue investigating their underexplored heritage and lasting influence on the built environment and the way it is perceived and lived in my new academic ‘adventure’

at TU Delft.

The history and current state of rural development in Africa is filled with grand ambitions and extraordinary promises. If, as I believe, the role of the historian is to deconstruct these narratives, it is just as relevant to examine how they have failed

and sometimes left little trace as it is to address the significant impacts of the 'successful' ones. Initiatives like Tanzania's Groundnut Scheme and the Ujamaa villagization program show how ambitious, top-down interventions can shape spatial organization

and reveal the consequences of overlooking local contexts. Alongside the classics of political, historical, and anthropological literature on this topic, I would credit Adam Guerin, whose essay on the Gharb Valley in Morocco2 first

introduced me to the value of this perspective and is something I wish I had explored further in my doctoral research.

In a way, this led me to question how to give voice and strength to minor narratives, and my journey to Gambia was crucial in this. They provide an invaluable lens for uncovering the richness and complexity of cultural landscapes. Stories of economic practices, displacement, and adaptation—often overshadowed by dominant historical accounts—can reveal alternative histories and nuanced identities. Embracing these minor narratives within architectural research has the potential to contribute to more inclusive, contextually relevant, and culturally enriched built environments. The question of how effectively these can be addressed in a discipline like ours, which easily succumbs to the allure of the grand and the oversized, remains open for me.

Fig. 8; 9: The view from some of the places I've stayed at over the past few months.

Apart from all the challenges of traveling through unfamiliar and not always easily accessible places, one of the hardest tasks has been to convey this experience without omitting its ambiguities and emotional aspects, while simultaneously doing my best

to avoid falling into the many clichés of exotic travel literature, especially those often applied to Africa: overcrowded cities, heavy traffic, untouched nature, and unsettling economic divides. Above all, I made every effort to avoid aestheticizing

poverty while also not ignoring its existence. Like any experience, this one is refracted through my own preconceptions, habits, and the cultures of my home countries. I hope, at least in part, to have avoided presenting a distorted image of the places

I visited and the stories shared with me.

The most interesting aspects of this experiences have been possible solely thanks to the people I have met during these months. Some of them were old friends, while others may become so. I thank them for their generosity. There have also been conflicts

and disappointments, more in the background than during these months of travel. I don’t want to come across as overly sentimental, but I have learned from these experiences as well.

I’m bringing home many vivid memories and a curiosity about many stories that I could only get to know superficially. Among the goals I set for myself and those who funded me, there was no specific research output. Alas, I didn't have any revolutionary methodological insights. However, I experimented with ways of writing about my work that are unusual for me, I read and saw a lot. That already feels like quite a lot to me.

Fig. 10; 11: Abandoned factory and company housing

Fig. 12: The custodian of the former INERA staff social club closes the theater doors behind us.

-----------------------------------

[1] To mention just a few recent references, among many, that have influenced me in drafting these notes: Jasper Ludewig’s work as part of this same fellowship on the impact of fertilizers, Will Davis’s ongoing research on “Plantation

Architectures,” and the project that initially sparked my interest, in which I participated, soon to publish its summary volume: Fisher, A., et al., *Modernist Reinventions of the Rural Landscapes*, Routledge.

[2] Adam Guerin (2016) “Disaster Ecologies: Land, Peoples, and the Colonial Modern in the Gharb, Morocco, 1911-1936”, Journal of Social and Economic Studies of the Orient, 59:3.

2024 Recipients

Architecture, Agriculture, and What Was Left Behind

Nov 13, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this fourth installment of his travel blog, he reflects on his travels and makes a case for studying the 'minor narratives' that appear when we read architecture as a manifestation of power dynamics. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo"

Part Two: "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future"

Part Three: "One-crop country: Agricultural and Trading Heritage in Gambia"

__________________________________________________________________

It might be slightly unusual, but not unique1, to discuss agriculture, or agribusiness, within the context of architecture. There is no doubt —and I've reflected on this a lot over the past months—that the challenge I set for myself,

which the Society of Architectural Historians trusted me to undertake, stems from a personal obsession to seek architecture beyond itself, in the relationships it establishes with other disciplines and in contexts that might seem less than obvious.

More than once, when explaining the purpose of my journey, I noticed a hint of confusion in my listeners. Perhaps because of my own muddled explanations. What could palm oil and groundnuts possibly have to say to someone interested in architectural

history?

This always required an additional layer of explanation, connecting these to objects more familiar to the discipline’s traditional image: company towns, industrial complexes, markets, ports, and infrastructure. Yet, it remained a challenge to convince

people that, despite my ignorance of botany, agronomy, or industrial engineering, I am genuinely interested in the processes involved in palm oil extraction, in the life cycle of a plantation, or in groundnut storage. An interest driven by a naïve

enthusiasm—perhaps like that of an amateur who constantly rediscovers the obvious with amazement.

And yet, the pervasive influence of food production and consumption chains has implications for our built environment. They shape not only rural landscapes but also urban infrastructures. They extend their reach into nearly every aspect of daily life—impacting

logistics, transportation networks, and even housing. Production and consumption chains, as they unfold across time and geography, become a network linking locales that may appear remote to the Western eye with major industrial and port centers on

national, continental, and global scales.

Through this web, distant agricultural zones and small-scale production sites are integrated into vast supply chains, feeding into the rhythms of industrial powerhouses and trade hubs. Agribusiness creates a spatial continuity that binds seemingly disparate

regions into a shared, though uneven, economic landscape. The architecture and infrastructure that emerge from this dynamic shape a world where rural outposts and urban centers are interdependent, reflecting the economic forces that connect them across

vast distances.

Physically visiting these places means experiencing this connection firsthand. It reveals the tangible presence of this vast network. It also powerfully highlights the extraordinary contrast between globalization’s promises of progress and the deeply

rooted realities on the ground. Despite the narrative of development and opportunity that globalization professes, the entrenched practices of extraction and labor exploitation reveal an uneven exchange, one that continues to shape the built environment,

social structures, and local realities of these regions.

Defunct plantations, leaving the communities that once gathered around them even more abandoned, revive patterns deeply rooted in centuries of history. Monumental—and failed—projects aimed at social and economic transformation in rural areas

reflect the inherent violence of ideology, often regardless of its orientation, or the subtler violence masked by the seemingly neutral hegemony of technical knowledge. These sites tell stories of abandoned promises and disrupted livelihoods, where

aspirations for progress clash with the realities on the ground, creating landscapes marked by both ambition and neglect.

These models, which for centuries has aligned with the colonial exploitation of natural resources and, more often than not, the brutal subjugation of local populations, survived, and often thrived throughout decolonization and persists in various forms

today. In these encounters, the structural inequalities embedded within the global agribusiness chains become vividly apparent, underscoring a legacy that remains woven into the fabric of rural economies and landscapes.

In this sense, if we believe in architecture’s role to materialize power dynamics—relationships that are both tangible and measurable within the collective imagination, accumulated cultural material, and its narratives—then palm oil and groundnuts become as relevant as cement and steel. They shape landscapes and communities just as decisively, embodying a physical manifestation of economic and social forces that architecture has the potential to reveal.

Fig. 1: A coffee plant nursery in Yangambi

Fig. 2; 3: A backlit panel illustrating the absorption and evaporation cycle for maize cultivation. INERA.

Much of what I saw and learned has been left out of the notes published here—partly for narrative coherence, partly because I couldn’t find a compelling way to present it, and partly because I wanted to spare the reader the tedium of details

and episodes that seemed more relevant to me personally than to others. Some traces of this journey can also be found in the SAHARA image platform, still too sparse on content from the African continent, to which I’ve made a modest contribution.

Among the architectural artifacts that didn’t make it into my previous travel notes, but to which I’ve become somewhat attached, are a few of Kinshasa’s landmarks: the RTNC tower, which I was able to visit after some bureaucratic hurdles

and the help of many; my favorite monument, the Limete Tower; as well as the SOZACOM tower and the CCIZ building (now the Fleuve Congo Hotel). Other sites include the UniKin campus, Karume’s Zanzibar New Town, the university campus and the old

port in Dar es Salaam.

Thanks to the flexibility granted by the SAH in managing the travel schedule, I was able to enrich my journey with additional experiences, which allowed me to extend my stay in Kinshasa by a few weeks and gain a more tangible sense of the city. Among the most vivid memories are those from the artist residency and the small exhibition organized in collaboration with friends at Laboratoire Kontempo and Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, co-funded by the University of Liverpool. These experiences stand out not only for the memories they left behind but also, perhaps especially, for the challenges we encountered along the way, which didn’t prevent us from achieving even more than we had anticipated.

Fig. 4; 5: The Congolese National Radio and Television building. View of the entrance and the entrance lobby.

Fig. 6: Merdi Tusumba Eduard and Anli Lukunku during the art residency at the Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, working on a model of Kinshasa as a tool to rethink the city's urban past and imagine its future. Learn more.

Fig. 7: My favorite monument, the Limete 'Interchange' Tower in Kinshasa, photographed as it should be, while speeding down the surrounding avenues.

During these months, I discovered and re-discovered an interest in rivers, failures, and minor narratives, and some traces of this can be found, more or less explicitly, in my published notes. Beyond a primordial fascination with rivers like the Congo

and the Gambia—which, not coincidentally, name two of the countries I visited—they emerged from my travels as powerful forces shaping settlement patterns, economic development, and even social hierarchies. Even the most superficial history

of Sub-Saharan Africa reveals how rivers like the Niger, Congo, Senegal, Volta, and Gambia have not only shaped the layout and development of cities and settlements but have also deeply influenced their architectural identity and the socio-political

and economic conditions underlying their urban histories. I aim to continue investigating their underexplored heritage and lasting influence on the built environment and the way it is perceived and lived in my new academic ‘adventure’

at TU Delft.

The history and current state of rural development in Africa is filled with grand ambitions and extraordinary promises. If, as I believe, the role of the historian is to deconstruct these narratives, it is just as relevant to examine how they have failed

and sometimes left little trace as it is to address the significant impacts of the 'successful' ones. Initiatives like Tanzania's Groundnut Scheme and the Ujamaa villagization program show how ambitious, top-down interventions can shape spatial organization

and reveal the consequences of overlooking local contexts. Alongside the classics of political, historical, and anthropological literature on this topic, I would credit Adam Guerin, whose essay on the Gharb Valley in Morocco2 first

introduced me to the value of this perspective and is something I wish I had explored further in my doctoral research.

In a way, this led me to question how to give voice and strength to minor narratives, and my journey to Gambia was crucial in this. They provide an invaluable lens for uncovering the richness and complexity of cultural landscapes. Stories of economic practices, displacement, and adaptation—often overshadowed by dominant historical accounts—can reveal alternative histories and nuanced identities. Embracing these minor narratives within architectural research has the potential to contribute to more inclusive, contextually relevant, and culturally enriched built environments. The question of how effectively these can be addressed in a discipline like ours, which easily succumbs to the allure of the grand and the oversized, remains open for me.

Fig. 8; 9: The view from some of the places I've stayed at over the past few months.

Apart from all the challenges of traveling through unfamiliar and not always easily accessible places, one of the hardest tasks has been to convey this experience without omitting its ambiguities and emotional aspects, while simultaneously doing my best

to avoid falling into the many clichés of exotic travel literature, especially those often applied to Africa: overcrowded cities, heavy traffic, untouched nature, and unsettling economic divides. Above all, I made every effort to avoid aestheticizing

poverty while also not ignoring its existence. Like any experience, this one is refracted through my own preconceptions, habits, and the cultures of my home countries. I hope, at least in part, to have avoided presenting a distorted image of the places

I visited and the stories shared with me.

The most interesting aspects of this experiences have been possible solely thanks to the people I have met during these months. Some of them were old friends, while others may become so. I thank them for their generosity. There have also been conflicts

and disappointments, more in the background than during these months of travel. I don’t want to come across as overly sentimental, but I have learned from these experiences as well.

I’m bringing home many vivid memories and a curiosity about many stories that I could only get to know superficially. Among the goals I set for myself and those who funded me, there was no specific research output. Alas, I didn't have any revolutionary methodological insights. However, I experimented with ways of writing about my work that are unusual for me, I read and saw a lot. That already feels like quite a lot to me.

Fig. 10; 11: Abandoned factory and company housing

Fig. 12: The custodian of the former INERA staff social club closes the theater doors behind us.

-----------------------------------

[1] To mention just a few recent references, among many, that have influenced me in drafting these notes: Jasper Ludewig’s work as part of this same fellowship on the impact of fertilizers, Will Davis’s ongoing research on “Plantation

Architectures,” and the project that initially sparked my interest, in which I participated, soon to publish its summary volume: Fisher, A., et al., *Modernist Reinventions of the Rural Landscapes*, Routledge.

[2] Adam Guerin (2016) “Disaster Ecologies: Land, Peoples, and the Colonial Modern in the Gharb, Morocco, 1911-1936”, Journal of Social and Economic Studies of the Orient, 59:3.

Architecture, Agriculture, and What Was Left Behind

Nov 13, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this fourth installment of his travel blog, he reflects on his travels and makes a case for studying the 'minor narratives' that appear when we read architecture as a manifestation of power dynamics. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo"

Part Two: "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future"

Part Three: "One-crop country: Agricultural and Trading Heritage in Gambia"

__________________________________________________________________

It might be slightly unusual, but not unique1, to discuss agriculture, or agribusiness, within the context of architecture. There is no doubt —and I've reflected on this a lot over the past months—that the challenge I set for myself,

which the Society of Architectural Historians trusted me to undertake, stems from a personal obsession to seek architecture beyond itself, in the relationships it establishes with other disciplines and in contexts that might seem less than obvious.

More than once, when explaining the purpose of my journey, I noticed a hint of confusion in my listeners. Perhaps because of my own muddled explanations. What could palm oil and groundnuts possibly have to say to someone interested in architectural

history?

This always required an additional layer of explanation, connecting these to objects more familiar to the discipline’s traditional image: company towns, industrial complexes, markets, ports, and infrastructure. Yet, it remained a challenge to convince

people that, despite my ignorance of botany, agronomy, or industrial engineering, I am genuinely interested in the processes involved in palm oil extraction, in the life cycle of a plantation, or in groundnut storage. An interest driven by a naïve

enthusiasm—perhaps like that of an amateur who constantly rediscovers the obvious with amazement.

And yet, the pervasive influence of food production and consumption chains has implications for our built environment. They shape not only rural landscapes but also urban infrastructures. They extend their reach into nearly every aspect of daily life—impacting

logistics, transportation networks, and even housing. Production and consumption chains, as they unfold across time and geography, become a network linking locales that may appear remote to the Western eye with major industrial and port centers on

national, continental, and global scales.

Through this web, distant agricultural zones and small-scale production sites are integrated into vast supply chains, feeding into the rhythms of industrial powerhouses and trade hubs. Agribusiness creates a spatial continuity that binds seemingly disparate

regions into a shared, though uneven, economic landscape. The architecture and infrastructure that emerge from this dynamic shape a world where rural outposts and urban centers are interdependent, reflecting the economic forces that connect them across

vast distances.

Physically visiting these places means experiencing this connection firsthand. It reveals the tangible presence of this vast network. It also powerfully highlights the extraordinary contrast between globalization’s promises of progress and the deeply

rooted realities on the ground. Despite the narrative of development and opportunity that globalization professes, the entrenched practices of extraction and labor exploitation reveal an uneven exchange, one that continues to shape the built environment,

social structures, and local realities of these regions.

Defunct plantations, leaving the communities that once gathered around them even more abandoned, revive patterns deeply rooted in centuries of history. Monumental—and failed—projects aimed at social and economic transformation in rural areas

reflect the inherent violence of ideology, often regardless of its orientation, or the subtler violence masked by the seemingly neutral hegemony of technical knowledge. These sites tell stories of abandoned promises and disrupted livelihoods, where

aspirations for progress clash with the realities on the ground, creating landscapes marked by both ambition and neglect.

These models, which for centuries has aligned with the colonial exploitation of natural resources and, more often than not, the brutal subjugation of local populations, survived, and often thrived throughout decolonization and persists in various forms

today. In these encounters, the structural inequalities embedded within the global agribusiness chains become vividly apparent, underscoring a legacy that remains woven into the fabric of rural economies and landscapes.

In this sense, if we believe in architecture’s role to materialize power dynamics—relationships that are both tangible and measurable within the collective imagination, accumulated cultural material, and its narratives—then palm oil and groundnuts become as relevant as cement and steel. They shape landscapes and communities just as decisively, embodying a physical manifestation of economic and social forces that architecture has the potential to reveal.

Fig. 1: A coffee plant nursery in Yangambi

Fig. 2; 3: A backlit panel illustrating the absorption and evaporation cycle for maize cultivation. INERA.

Much of what I saw and learned has been left out of the notes published here—partly for narrative coherence, partly because I couldn’t find a compelling way to present it, and partly because I wanted to spare the reader the tedium of details

and episodes that seemed more relevant to me personally than to others. Some traces of this journey can also be found in the SAHARA image platform, still too sparse on content from the African continent, to which I’ve made a modest contribution.

Among the architectural artifacts that didn’t make it into my previous travel notes, but to which I’ve become somewhat attached, are a few of Kinshasa’s landmarks: the RTNC tower, which I was able to visit after some bureaucratic hurdles

and the help of many; my favorite monument, the Limete Tower; as well as the SOZACOM tower and the CCIZ building (now the Fleuve Congo Hotel). Other sites include the UniKin campus, Karume’s Zanzibar New Town, the university campus and the old

port in Dar es Salaam.

Thanks to the flexibility granted by the SAH in managing the travel schedule, I was able to enrich my journey with additional experiences, which allowed me to extend my stay in Kinshasa by a few weeks and gain a more tangible sense of the city. Among the most vivid memories are those from the artist residency and the small exhibition organized in collaboration with friends at Laboratoire Kontempo and Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, co-funded by the University of Liverpool. These experiences stand out not only for the memories they left behind but also, perhaps especially, for the challenges we encountered along the way, which didn’t prevent us from achieving even more than we had anticipated.

Fig. 4; 5: The Congolese National Radio and Television building. View of the entrance and the entrance lobby.

Fig. 6: Merdi Tusumba Eduard and Anli Lukunku during the art residency at the Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, working on a model of Kinshasa as a tool to rethink the city's urban past and imagine its future. Learn more.

Fig. 7: My favorite monument, the Limete 'Interchange' Tower in Kinshasa, photographed as it should be, while speeding down the surrounding avenues.

During these months, I discovered and re-discovered an interest in rivers, failures, and minor narratives, and some traces of this can be found, more or less explicitly, in my published notes. Beyond a primordial fascination with rivers like the Congo

and the Gambia—which, not coincidentally, name two of the countries I visited—they emerged from my travels as powerful forces shaping settlement patterns, economic development, and even social hierarchies. Even the most superficial history

of Sub-Saharan Africa reveals how rivers like the Niger, Congo, Senegal, Volta, and Gambia have not only shaped the layout and development of cities and settlements but have also deeply influenced their architectural identity and the socio-political

and economic conditions underlying their urban histories. I aim to continue investigating their underexplored heritage and lasting influence on the built environment and the way it is perceived and lived in my new academic ‘adventure’

at TU Delft.

The history and current state of rural development in Africa is filled with grand ambitions and extraordinary promises. If, as I believe, the role of the historian is to deconstruct these narratives, it is just as relevant to examine how they have failed

and sometimes left little trace as it is to address the significant impacts of the 'successful' ones. Initiatives like Tanzania's Groundnut Scheme and the Ujamaa villagization program show how ambitious, top-down interventions can shape spatial organization

and reveal the consequences of overlooking local contexts. Alongside the classics of political, historical, and anthropological literature on this topic, I would credit Adam Guerin, whose essay on the Gharb Valley in Morocco2 first

introduced me to the value of this perspective and is something I wish I had explored further in my doctoral research.

In a way, this led me to question how to give voice and strength to minor narratives, and my journey to Gambia was crucial in this. They provide an invaluable lens for uncovering the richness and complexity of cultural landscapes. Stories of economic practices, displacement, and adaptation—often overshadowed by dominant historical accounts—can reveal alternative histories and nuanced identities. Embracing these minor narratives within architectural research has the potential to contribute to more inclusive, contextually relevant, and culturally enriched built environments. The question of how effectively these can be addressed in a discipline like ours, which easily succumbs to the allure of the grand and the oversized, remains open for me.

Fig. 8; 9: The view from some of the places I've stayed at over the past few months.

Apart from all the challenges of traveling through unfamiliar and not always easily accessible places, one of the hardest tasks has been to convey this experience without omitting its ambiguities and emotional aspects, while simultaneously doing my best

to avoid falling into the many clichés of exotic travel literature, especially those often applied to Africa: overcrowded cities, heavy traffic, untouched nature, and unsettling economic divides. Above all, I made every effort to avoid aestheticizing

poverty while also not ignoring its existence. Like any experience, this one is refracted through my own preconceptions, habits, and the cultures of my home countries. I hope, at least in part, to have avoided presenting a distorted image of the places

I visited and the stories shared with me.

The most interesting aspects of this experiences have been possible solely thanks to the people I have met during these months. Some of them were old friends, while others may become so. I thank them for their generosity. There have also been conflicts

and disappointments, more in the background than during these months of travel. I don’t want to come across as overly sentimental, but I have learned from these experiences as well.

I’m bringing home many vivid memories and a curiosity about many stories that I could only get to know superficially. Among the goals I set for myself and those who funded me, there was no specific research output. Alas, I didn't have any revolutionary methodological insights. However, I experimented with ways of writing about my work that are unusual for me, I read and saw a lot. That already feels like quite a lot to me.

Fig. 10; 11: Abandoned factory and company housing

Fig. 12: The custodian of the former INERA staff social club closes the theater doors behind us.

-----------------------------------

[1] To mention just a few recent references, among many, that have influenced me in drafting these notes: Jasper Ludewig’s work as part of this same fellowship on the impact of fertilizers, Will Davis’s ongoing research on “Plantation

Architectures,” and the project that initially sparked my interest, in which I participated, soon to publish its summary volume: Fisher, A., et al., *Modernist Reinventions of the Rural Landscapes*, Routledge.

[2] Adam Guerin (2016) “Disaster Ecologies: Land, Peoples, and the Colonial Modern in the Gharb, Morocco, 1911-1936”, Journal of Social and Economic Studies of the Orient, 59:3.

2023 RECIPIENTS

Architecture, Agriculture, and What Was Left Behind

Nov 13, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this fourth installment of his travel blog, he reflects on his travels and makes a case for studying the 'minor narratives' that appear when we read architecture as a manifestation of power dynamics. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo"

Part Two: "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future"

Part Three: "One-crop country: Agricultural and Trading Heritage in Gambia"

__________________________________________________________________

It might be slightly unusual, but not unique1, to discuss agriculture, or agribusiness, within the context of architecture. There is no doubt —and I've reflected on this a lot over the past months—that the challenge I set for myself,

which the Society of Architectural Historians trusted me to undertake, stems from a personal obsession to seek architecture beyond itself, in the relationships it establishes with other disciplines and in contexts that might seem less than obvious.

More than once, when explaining the purpose of my journey, I noticed a hint of confusion in my listeners. Perhaps because of my own muddled explanations. What could palm oil and groundnuts possibly have to say to someone interested in architectural

history?

This always required an additional layer of explanation, connecting these to objects more familiar to the discipline’s traditional image: company towns, industrial complexes, markets, ports, and infrastructure. Yet, it remained a challenge to convince

people that, despite my ignorance of botany, agronomy, or industrial engineering, I am genuinely interested in the processes involved in palm oil extraction, in the life cycle of a plantation, or in groundnut storage. An interest driven by a naïve

enthusiasm—perhaps like that of an amateur who constantly rediscovers the obvious with amazement.

And yet, the pervasive influence of food production and consumption chains has implications for our built environment. They shape not only rural landscapes but also urban infrastructures. They extend their reach into nearly every aspect of daily life—impacting

logistics, transportation networks, and even housing. Production and consumption chains, as they unfold across time and geography, become a network linking locales that may appear remote to the Western eye with major industrial and port centers on

national, continental, and global scales.

Through this web, distant agricultural zones and small-scale production sites are integrated into vast supply chains, feeding into the rhythms of industrial powerhouses and trade hubs. Agribusiness creates a spatial continuity that binds seemingly disparate

regions into a shared, though uneven, economic landscape. The architecture and infrastructure that emerge from this dynamic shape a world where rural outposts and urban centers are interdependent, reflecting the economic forces that connect them across

vast distances.

Physically visiting these places means experiencing this connection firsthand. It reveals the tangible presence of this vast network. It also powerfully highlights the extraordinary contrast between globalization’s promises of progress and the deeply

rooted realities on the ground. Despite the narrative of development and opportunity that globalization professes, the entrenched practices of extraction and labor exploitation reveal an uneven exchange, one that continues to shape the built environment,

social structures, and local realities of these regions.

Defunct plantations, leaving the communities that once gathered around them even more abandoned, revive patterns deeply rooted in centuries of history. Monumental—and failed—projects aimed at social and economic transformation in rural areas

reflect the inherent violence of ideology, often regardless of its orientation, or the subtler violence masked by the seemingly neutral hegemony of technical knowledge. These sites tell stories of abandoned promises and disrupted livelihoods, where

aspirations for progress clash with the realities on the ground, creating landscapes marked by both ambition and neglect.

These models, which for centuries has aligned with the colonial exploitation of natural resources and, more often than not, the brutal subjugation of local populations, survived, and often thrived throughout decolonization and persists in various forms

today. In these encounters, the structural inequalities embedded within the global agribusiness chains become vividly apparent, underscoring a legacy that remains woven into the fabric of rural economies and landscapes.

In this sense, if we believe in architecture’s role to materialize power dynamics—relationships that are both tangible and measurable within the collective imagination, accumulated cultural material, and its narratives—then palm oil and groundnuts become as relevant as cement and steel. They shape landscapes and communities just as decisively, embodying a physical manifestation of economic and social forces that architecture has the potential to reveal.

Fig. 1: A coffee plant nursery in Yangambi

Fig. 2; 3: A backlit panel illustrating the absorption and evaporation cycle for maize cultivation. INERA.

Much of what I saw and learned has been left out of the notes published here—partly for narrative coherence, partly because I couldn’t find a compelling way to present it, and partly because I wanted to spare the reader the tedium of details

and episodes that seemed more relevant to me personally than to others. Some traces of this journey can also be found in the SAHARA image platform, still too sparse on content from the African continent, to which I’ve made a modest contribution.

Among the architectural artifacts that didn’t make it into my previous travel notes, but to which I’ve become somewhat attached, are a few of Kinshasa’s landmarks: the RTNC tower, which I was able to visit after some bureaucratic hurdles

and the help of many; my favorite monument, the Limete Tower; as well as the SOZACOM tower and the CCIZ building (now the Fleuve Congo Hotel). Other sites include the UniKin campus, Karume’s Zanzibar New Town, the university campus and the old

port in Dar es Salaam.

Thanks to the flexibility granted by the SAH in managing the travel schedule, I was able to enrich my journey with additional experiences, which allowed me to extend my stay in Kinshasa by a few weeks and gain a more tangible sense of the city. Among the most vivid memories are those from the artist residency and the small exhibition organized in collaboration with friends at Laboratoire Kontempo and Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, co-funded by the University of Liverpool. These experiences stand out not only for the memories they left behind but also, perhaps especially, for the challenges we encountered along the way, which didn’t prevent us from achieving even more than we had anticipated.

Fig. 4; 5: The Congolese National Radio and Television building. View of the entrance and the entrance lobby.

Fig. 6: Merdi Tusumba Eduard and Anli Lukunku during the art residency at the Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, working on a model of Kinshasa as a tool to rethink the city's urban past and imagine its future. Learn more.

Fig. 7: My favorite monument, the Limete 'Interchange' Tower in Kinshasa, photographed as it should be, while speeding down the surrounding avenues.

During these months, I discovered and re-discovered an interest in rivers, failures, and minor narratives, and some traces of this can be found, more or less explicitly, in my published notes. Beyond a primordial fascination with rivers like the Congo

and the Gambia—which, not coincidentally, name two of the countries I visited—they emerged from my travels as powerful forces shaping settlement patterns, economic development, and even social hierarchies. Even the most superficial history

of Sub-Saharan Africa reveals how rivers like the Niger, Congo, Senegal, Volta, and Gambia have not only shaped the layout and development of cities and settlements but have also deeply influenced their architectural identity and the socio-political

and economic conditions underlying their urban histories. I aim to continue investigating their underexplored heritage and lasting influence on the built environment and the way it is perceived and lived in my new academic ‘adventure’

at TU Delft.

The history and current state of rural development in Africa is filled with grand ambitions and extraordinary promises. If, as I believe, the role of the historian is to deconstruct these narratives, it is just as relevant to examine how they have failed

and sometimes left little trace as it is to address the significant impacts of the 'successful' ones. Initiatives like Tanzania's Groundnut Scheme and the Ujamaa villagization program show how ambitious, top-down interventions can shape spatial organization

and reveal the consequences of overlooking local contexts. Alongside the classics of political, historical, and anthropological literature on this topic, I would credit Adam Guerin, whose essay on the Gharb Valley in Morocco2 first

introduced me to the value of this perspective and is something I wish I had explored further in my doctoral research.

In a way, this led me to question how to give voice and strength to minor narratives, and my journey to Gambia was crucial in this. They provide an invaluable lens for uncovering the richness and complexity of cultural landscapes. Stories of economic practices, displacement, and adaptation—often overshadowed by dominant historical accounts—can reveal alternative histories and nuanced identities. Embracing these minor narratives within architectural research has the potential to contribute to more inclusive, contextually relevant, and culturally enriched built environments. The question of how effectively these can be addressed in a discipline like ours, which easily succumbs to the allure of the grand and the oversized, remains open for me.

Fig. 8; 9: The view from some of the places I've stayed at over the past few months.

Apart from all the challenges of traveling through unfamiliar and not always easily accessible places, one of the hardest tasks has been to convey this experience without omitting its ambiguities and emotional aspects, while simultaneously doing my best

to avoid falling into the many clichés of exotic travel literature, especially those often applied to Africa: overcrowded cities, heavy traffic, untouched nature, and unsettling economic divides. Above all, I made every effort to avoid aestheticizing

poverty while also not ignoring its existence. Like any experience, this one is refracted through my own preconceptions, habits, and the cultures of my home countries. I hope, at least in part, to have avoided presenting a distorted image of the places

I visited and the stories shared with me.

The most interesting aspects of this experiences have been possible solely thanks to the people I have met during these months. Some of them were old friends, while others may become so. I thank them for their generosity. There have also been conflicts

and disappointments, more in the background than during these months of travel. I don’t want to come across as overly sentimental, but I have learned from these experiences as well.

I’m bringing home many vivid memories and a curiosity about many stories that I could only get to know superficially. Among the goals I set for myself and those who funded me, there was no specific research output. Alas, I didn't have any revolutionary methodological insights. However, I experimented with ways of writing about my work that are unusual for me, I read and saw a lot. That already feels like quite a lot to me.

Fig. 10; 11: Abandoned factory and company housing

Fig. 12: The custodian of the former INERA staff social club closes the theater doors behind us.

-----------------------------------

[1] To mention just a few recent references, among many, that have influenced me in drafting these notes: Jasper Ludewig’s work as part of this same fellowship on the impact of fertilizers, Will Davis’s ongoing research on “Plantation

Architectures,” and the project that initially sparked my interest, in which I participated, soon to publish its summary volume: Fisher, A., et al., *Modernist Reinventions of the Rural Landscapes*, Routledge.

[2] Adam Guerin (2016) “Disaster Ecologies: Land, Peoples, and the Colonial Modern in the Gharb, Morocco, 1911-1936”, Journal of Social and Economic Studies of the Orient, 59:3.

Architecture, Agriculture, and What Was Left Behind

Nov 13, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this fourth installment of his travel blog, he reflects on his travels and makes a case for studying the 'minor narratives' that appear when we read architecture as a manifestation of power dynamics. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo"

Part Two: "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future"

Part Three: "One-crop country: Agricultural and Trading Heritage in Gambia"

__________________________________________________________________

It might be slightly unusual, but not unique1, to discuss agriculture, or agribusiness, within the context of architecture. There is no doubt —and I've reflected on this a lot over the past months—that the challenge I set for myself,

which the Society of Architectural Historians trusted me to undertake, stems from a personal obsession to seek architecture beyond itself, in the relationships it establishes with other disciplines and in contexts that might seem less than obvious.

More than once, when explaining the purpose of my journey, I noticed a hint of confusion in my listeners. Perhaps because of my own muddled explanations. What could palm oil and groundnuts possibly have to say to someone interested in architectural

history?

This always required an additional layer of explanation, connecting these to objects more familiar to the discipline’s traditional image: company towns, industrial complexes, markets, ports, and infrastructure. Yet, it remained a challenge to convince

people that, despite my ignorance of botany, agronomy, or industrial engineering, I am genuinely interested in the processes involved in palm oil extraction, in the life cycle of a plantation, or in groundnut storage. An interest driven by a naïve

enthusiasm—perhaps like that of an amateur who constantly rediscovers the obvious with amazement.

And yet, the pervasive influence of food production and consumption chains has implications for our built environment. They shape not only rural landscapes but also urban infrastructures. They extend their reach into nearly every aspect of daily life—impacting

logistics, transportation networks, and even housing. Production and consumption chains, as they unfold across time and geography, become a network linking locales that may appear remote to the Western eye with major industrial and port centers on

national, continental, and global scales.

Through this web, distant agricultural zones and small-scale production sites are integrated into vast supply chains, feeding into the rhythms of industrial powerhouses and trade hubs. Agribusiness creates a spatial continuity that binds seemingly disparate

regions into a shared, though uneven, economic landscape. The architecture and infrastructure that emerge from this dynamic shape a world where rural outposts and urban centers are interdependent, reflecting the economic forces that connect them across

vast distances.

Physically visiting these places means experiencing this connection firsthand. It reveals the tangible presence of this vast network. It also powerfully highlights the extraordinary contrast between globalization’s promises of progress and the deeply

rooted realities on the ground. Despite the narrative of development and opportunity that globalization professes, the entrenched practices of extraction and labor exploitation reveal an uneven exchange, one that continues to shape the built environment,

social structures, and local realities of these regions.

Defunct plantations, leaving the communities that once gathered around them even more abandoned, revive patterns deeply rooted in centuries of history. Monumental—and failed—projects aimed at social and economic transformation in rural areas

reflect the inherent violence of ideology, often regardless of its orientation, or the subtler violence masked by the seemingly neutral hegemony of technical knowledge. These sites tell stories of abandoned promises and disrupted livelihoods, where

aspirations for progress clash with the realities on the ground, creating landscapes marked by both ambition and neglect.

These models, which for centuries has aligned with the colonial exploitation of natural resources and, more often than not, the brutal subjugation of local populations, survived, and often thrived throughout decolonization and persists in various forms

today. In these encounters, the structural inequalities embedded within the global agribusiness chains become vividly apparent, underscoring a legacy that remains woven into the fabric of rural economies and landscapes.

In this sense, if we believe in architecture’s role to materialize power dynamics—relationships that are both tangible and measurable within the collective imagination, accumulated cultural material, and its narratives—then palm oil and groundnuts become as relevant as cement and steel. They shape landscapes and communities just as decisively, embodying a physical manifestation of economic and social forces that architecture has the potential to reveal.

Fig. 1: A coffee plant nursery in Yangambi

Fig. 2; 3: A backlit panel illustrating the absorption and evaporation cycle for maize cultivation. INERA.

Much of what I saw and learned has been left out of the notes published here—partly for narrative coherence, partly because I couldn’t find a compelling way to present it, and partly because I wanted to spare the reader the tedium of details

and episodes that seemed more relevant to me personally than to others. Some traces of this journey can also be found in the SAHARA image platform, still too sparse on content from the African continent, to which I’ve made a modest contribution.

Among the architectural artifacts that didn’t make it into my previous travel notes, but to which I’ve become somewhat attached, are a few of Kinshasa’s landmarks: the RTNC tower, which I was able to visit after some bureaucratic hurdles

and the help of many; my favorite monument, the Limete Tower; as well as the SOZACOM tower and the CCIZ building (now the Fleuve Congo Hotel). Other sites include the UniKin campus, Karume’s Zanzibar New Town, the university campus and the old

port in Dar es Salaam.

Thanks to the flexibility granted by the SAH in managing the travel schedule, I was able to enrich my journey with additional experiences, which allowed me to extend my stay in Kinshasa by a few weeks and gain a more tangible sense of the city. Among the most vivid memories are those from the artist residency and the small exhibition organized in collaboration with friends at Laboratoire Kontempo and Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, co-funded by the University of Liverpool. These experiences stand out not only for the memories they left behind but also, perhaps especially, for the challenges we encountered along the way, which didn’t prevent us from achieving even more than we had anticipated.

Fig. 4; 5: The Congolese National Radio and Television building. View of the entrance and the entrance lobby.

Fig. 6: Merdi Tusumba Eduard and Anli Lukunku during the art residency at the Centre Culturel Mokili na Poche, working on a model of Kinshasa as a tool to rethink the city's urban past and imagine its future. Learn more.

Fig. 7: My favorite monument, the Limete 'Interchange' Tower in Kinshasa, photographed as it should be, while speeding down the surrounding avenues.

During these months, I discovered and re-discovered an interest in rivers, failures, and minor narratives, and some traces of this can be found, more or less explicitly, in my published notes. Beyond a primordial fascination with rivers like the Congo

and the Gambia—which, not coincidentally, name two of the countries I visited—they emerged from my travels as powerful forces shaping settlement patterns, economic development, and even social hierarchies. Even the most superficial history

of Sub-Saharan Africa reveals how rivers like the Niger, Congo, Senegal, Volta, and Gambia have not only shaped the layout and development of cities and settlements but have also deeply influenced their architectural identity and the socio-political