-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The prestigious H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship allows a recent graduate or emerging scholar to study by travel for one year while observing, reading, writing, or sketching. Fellowship recipients are required to document their travels through monthly posts on the SAH Blog.

2025 Amalie Elfallah

2025 Francesca Sisci

2024 Michele Tenzon

2024 Stathis G. Yeros

2023 Jasper Ludewig

2023 Annie Schentag

2022 Anne Delano Steinert

2022 Adil Mansure

2019 Sundus Al-Bayati

2018 Aymar Mariño-Maza

2018 Zachary J. Violette

2017 Sarah Rovang

2016 Adeyemi Akande

2015 Danielle S. Willkens

2014 Patricia Blessing

2013 Amber N. Wiley

2025 Recipients

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Jul 29, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this second installment of his travel blog, he recounts his encounters across Tanzania. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo."

------

Kaitu, who accompanied us for part of this trip, is very talkative and boundlessly generous. He now lives and teaches at the University in Dar es Salaam, but like most of the people I spoke with in this city, his origins are elsewhere. He was born in Bukoba, in the Northwest of Tanzania, along the shores of the Lake Victoria. After many years living abroad in Belgium, he is now back in his home country and is quickly readapting to a lifestyle, culture, and city to which he always knew he would eventually return. During the few weeks of my stay in Tanzania, he largely made up for my lack of experience of the country.

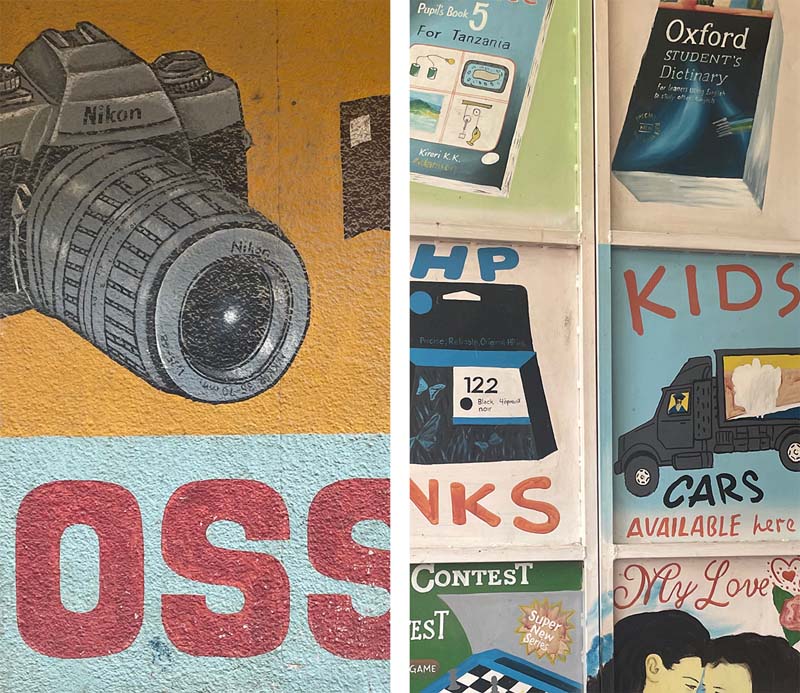

We’ve been driving for less than an hour on Bagamoyo Road, and he has already reviewed 50 years of post-independence Tanzanian political history for us. The avenue runs in north-south direction, parallel to the coast, and links Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, to Bagamoyo, the old capital of German East Africa and formerly an important trading centre. On the east side of the road, rows of hotels facing the ocean are punctuated by shopping malls covered in advertising signs written in Chinese. Lucia joins me for this part of the trip. She had never been to Africa before and is excited by the tropical setting and the customizations of buses and bajajis, the painted shop signs, and only slightly intimidated by the overcrowded Kariakoo market.

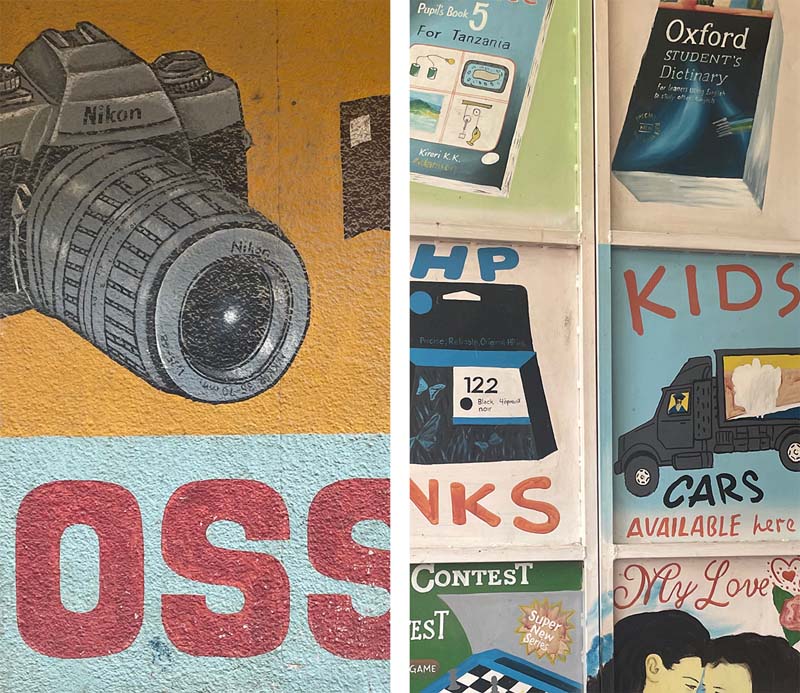

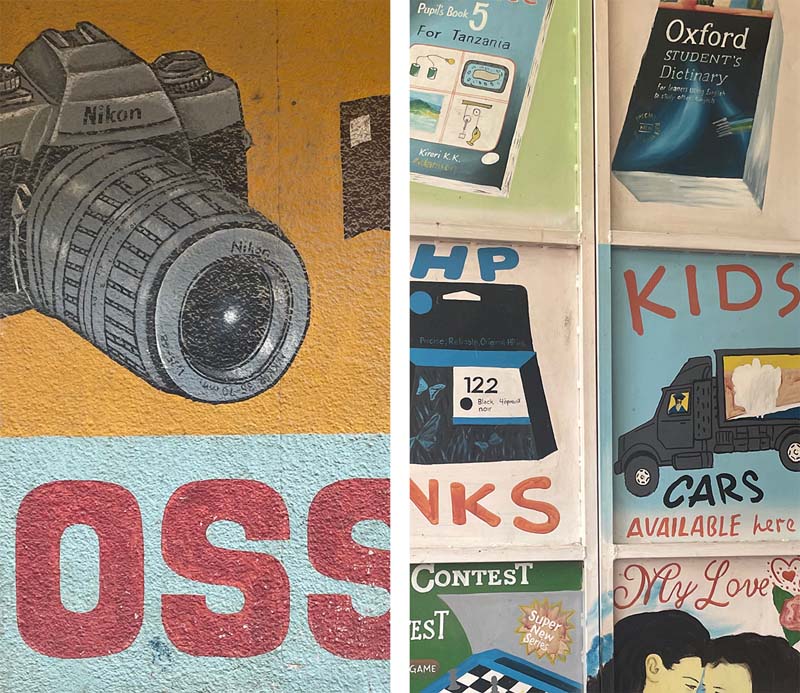

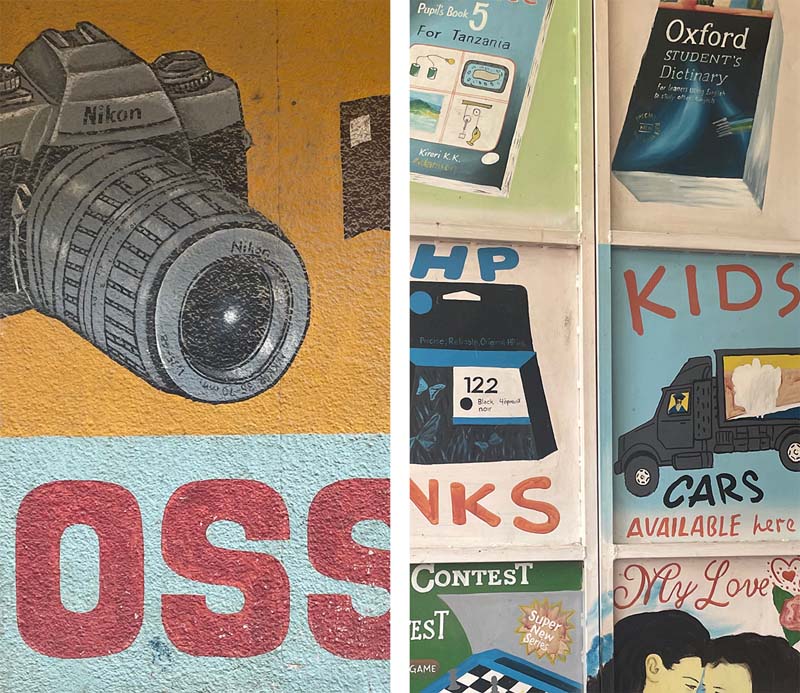

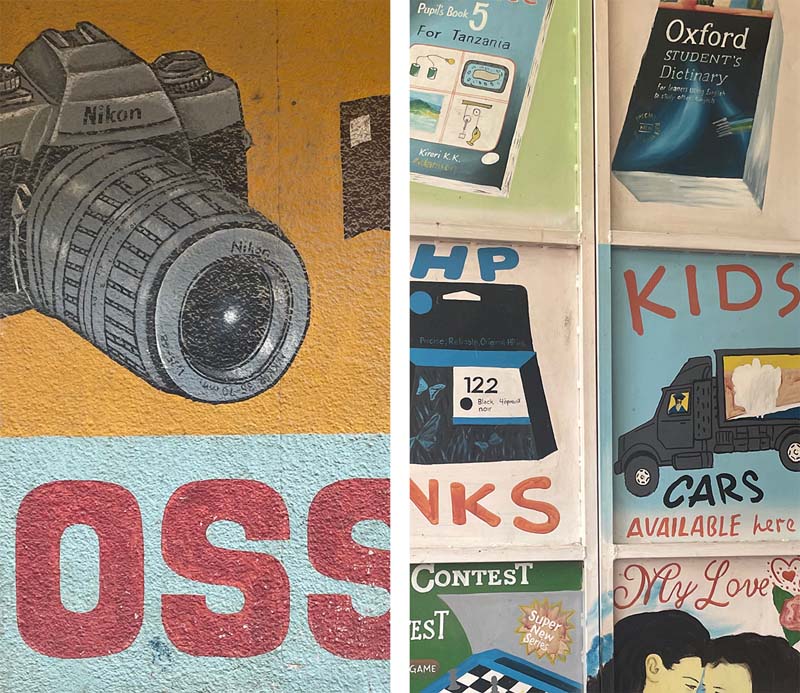

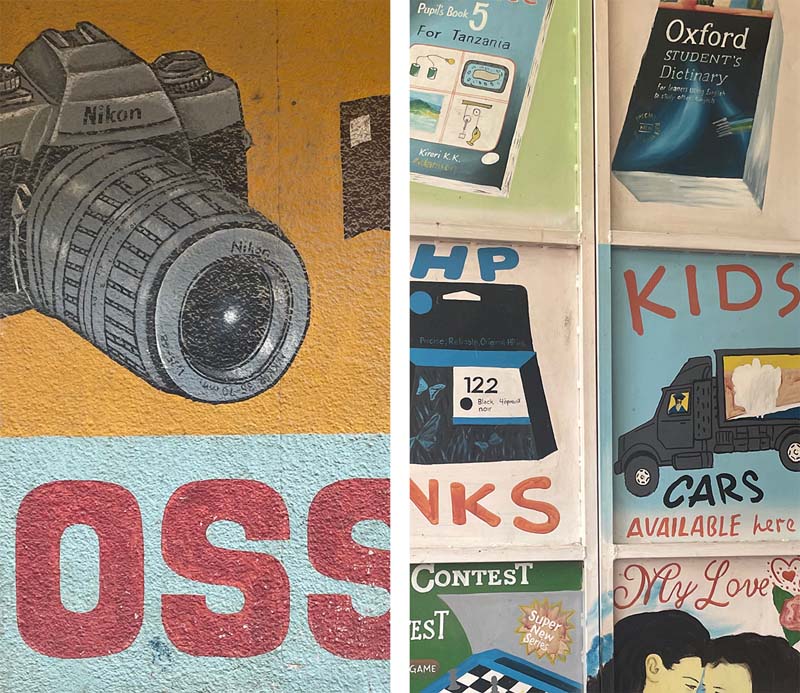

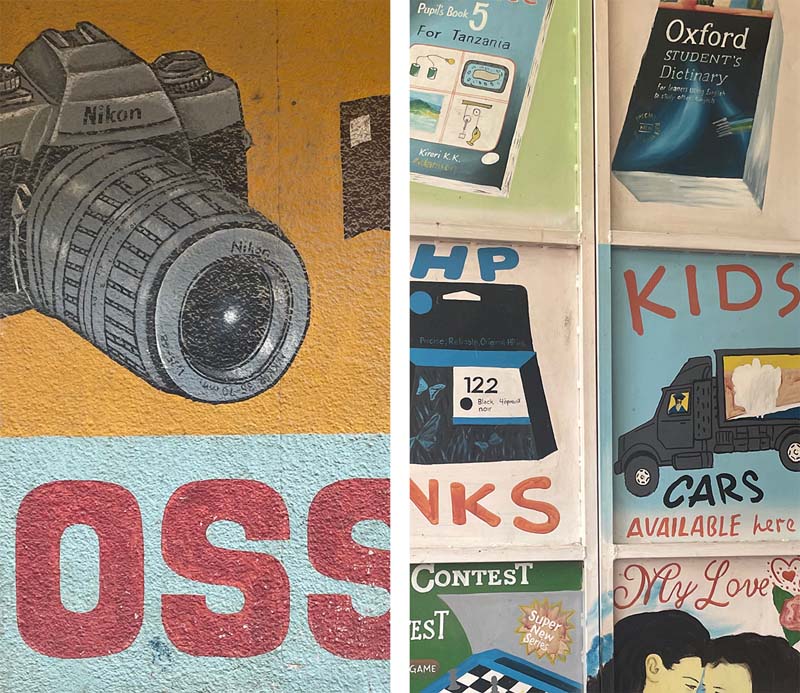

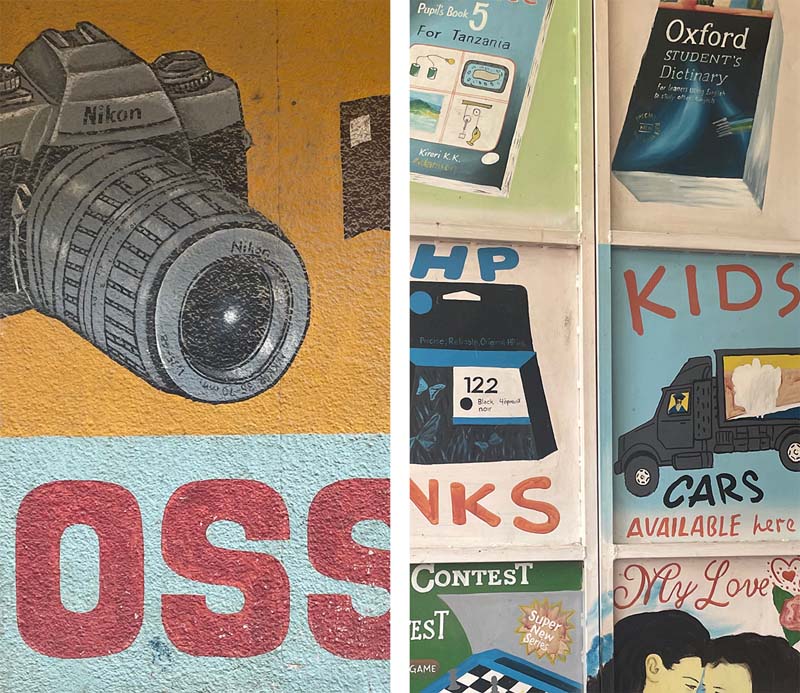

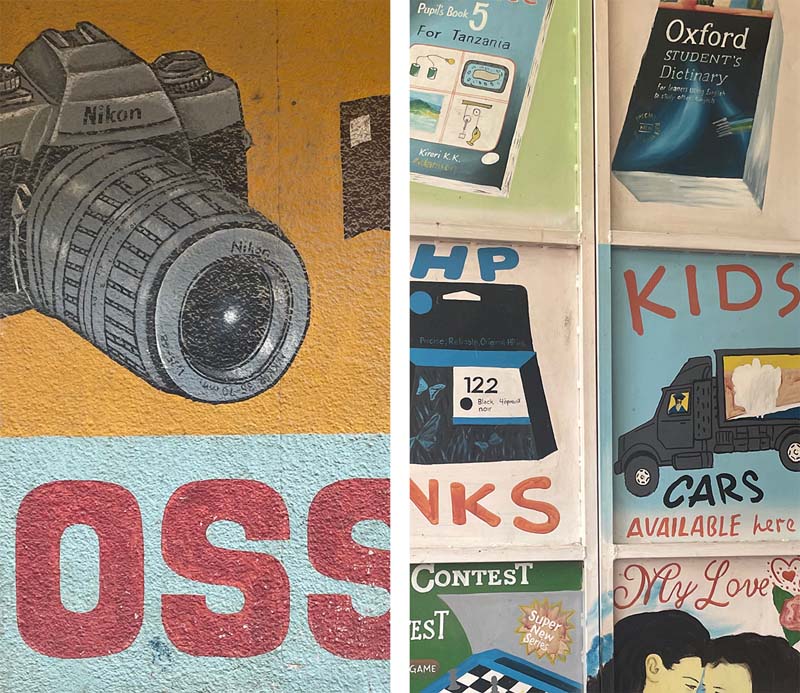

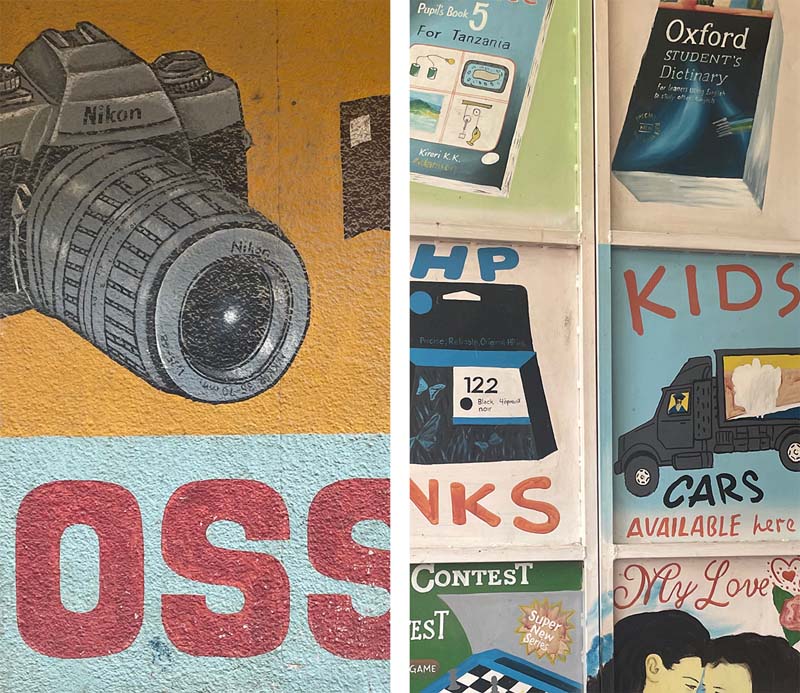

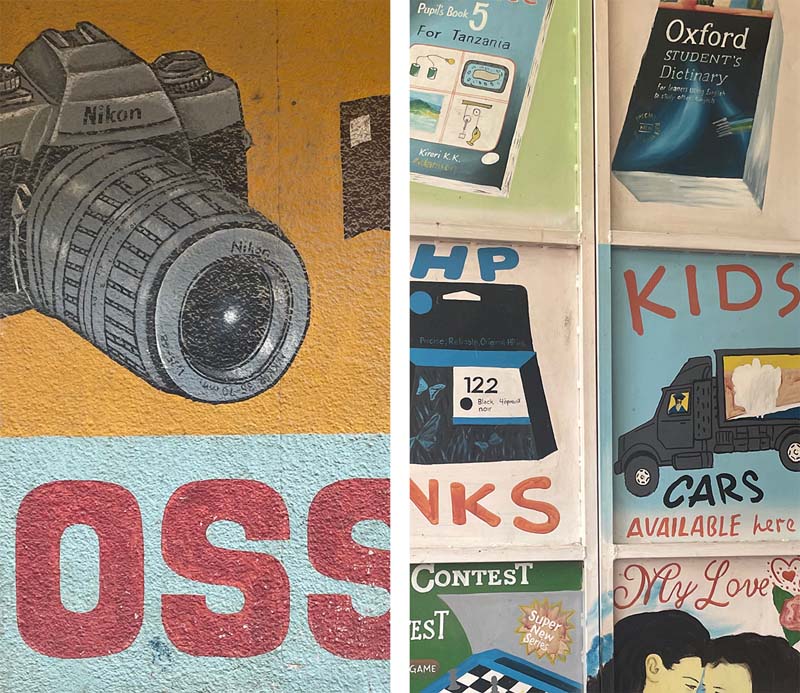

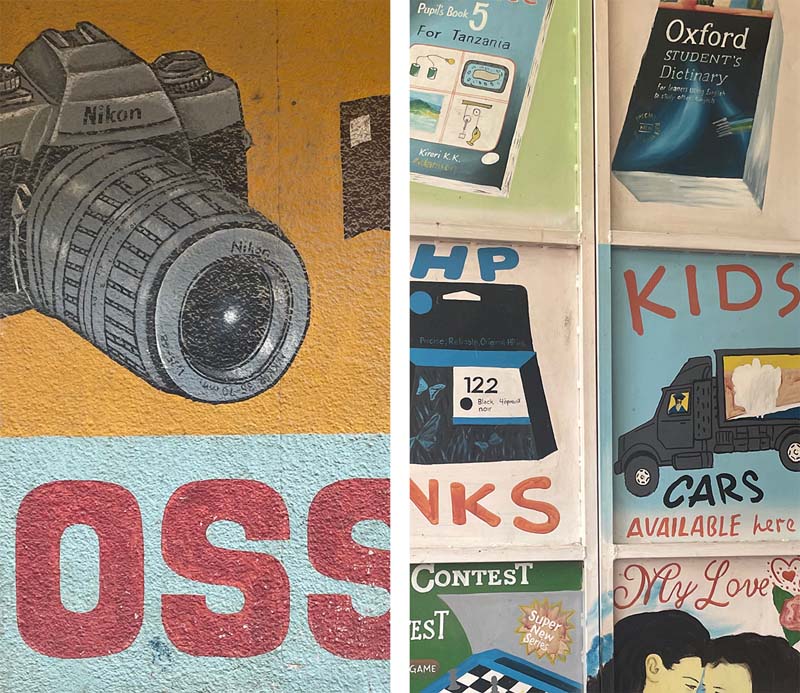

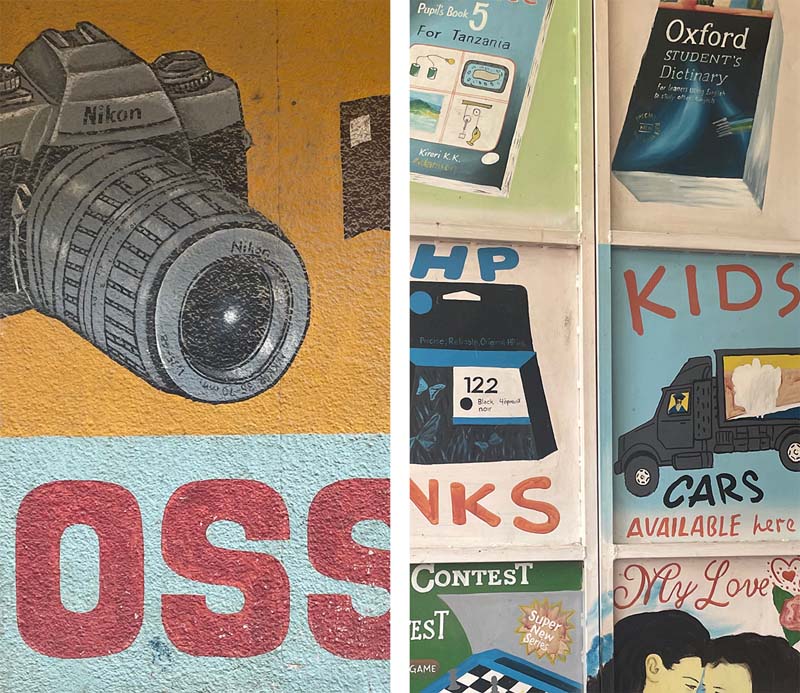

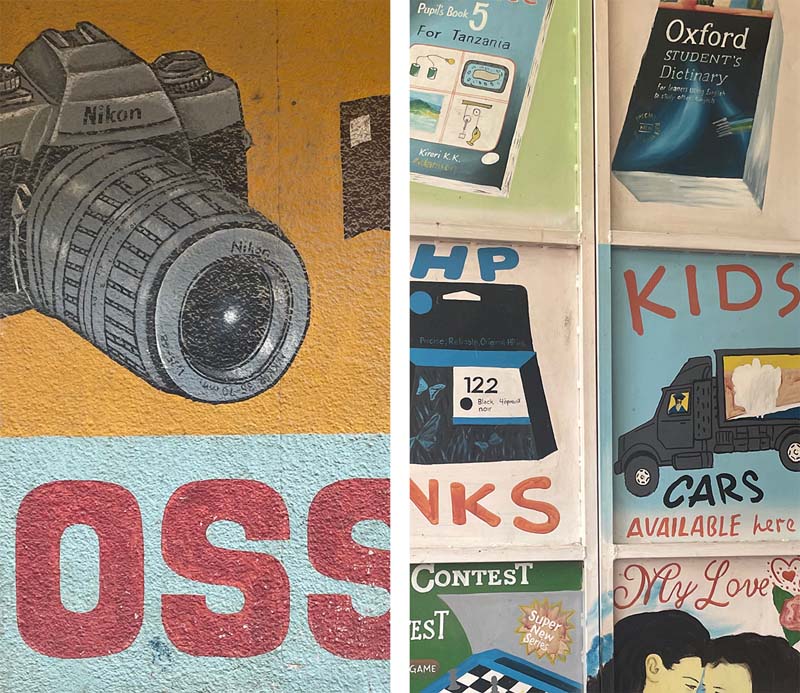

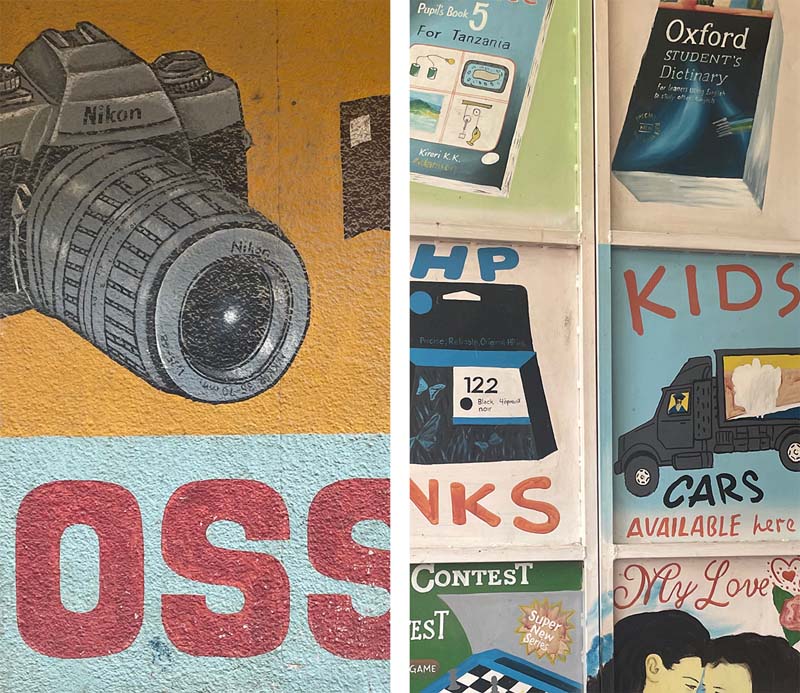

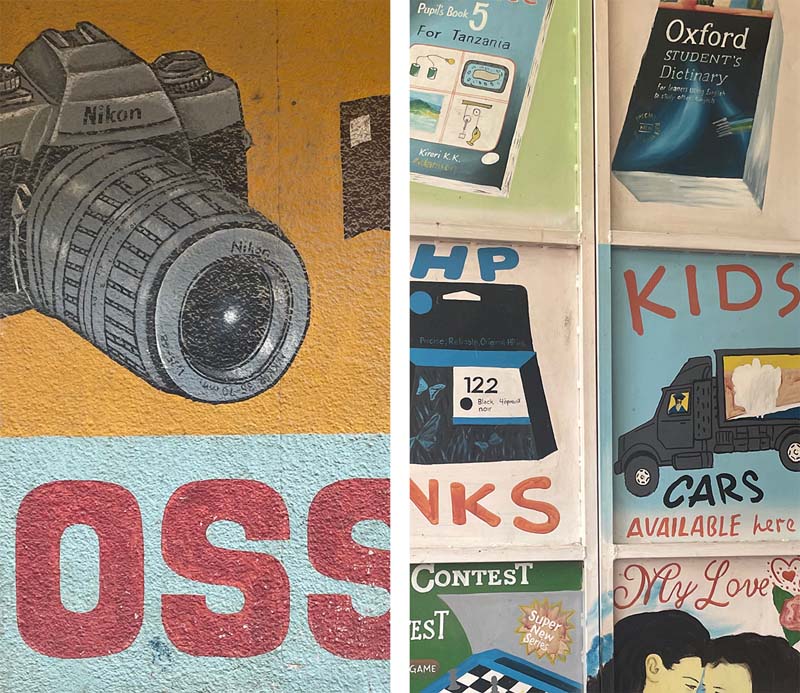

Painted shop signs in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma

The covered market in the Kariakoo district, Dar es Salaam. Opened in 1974 and designed by Beda Amuli, who established the first African architectural firm across East and Central Africa.

Tanzania gained independence from British rule in 1961, and the stories that guide the trajectory of this trip have their roots in colonial history and much of their development in independent Tanzania. These stories show, once again, that political milestones like independence are not clear-cut boundaries but are hinges of change, whose trajectory is largely defined by the conditions and visions of the future inherited by the generation responsible for such transition.

There are many ways to approach and tell this story. The one I have chosen is certainly partial. It draws from another chapter—adding to the one recounted in my previous travel report—of the broad history of how the natural resources of the African continent and the opportunities they offered for large-scale agricultural development have been the subject of ambitious projects for transforming the countryside. In Tanzania, these projects have served as a testing ground for the creation of an independent state and a new national identity. This process has made the countryside central to discussions where Western views differ significantly from local opinions. Although this journey cannot settle these differences, it provides an opportunity for them to emerge through encounters with the places and people who have experienced such change firsthand.

Mwalimu

Kaitu’s opinions on the recent political history of his country are generally cautious. He carefully weighs the pros and cons. Yet, on two things he seems to have no doubt. The first is that Julius Nyerere, the last Prime Minister of British Tanganyika and the first (and much revered) president of independent Tanzania— also known as ‘Mwalimu’ (‘teacher’ in Swahili) — has been the most important political figure in the country's history. The second is that Ujamaa, Nyerere’s political philosophy of choice marketed as the African original way to socialism, is responsible for making the country what it is despite the mistakes made in its implementation.

Nyerere square in Dodoma

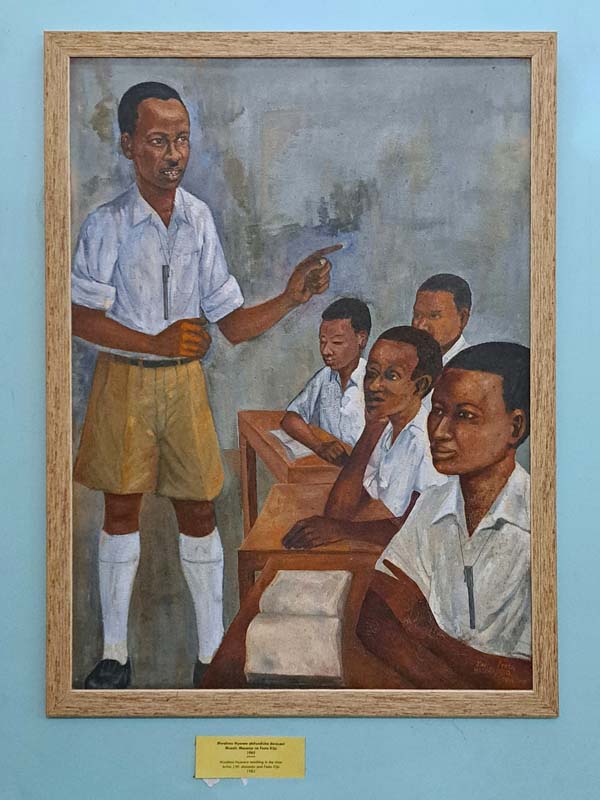

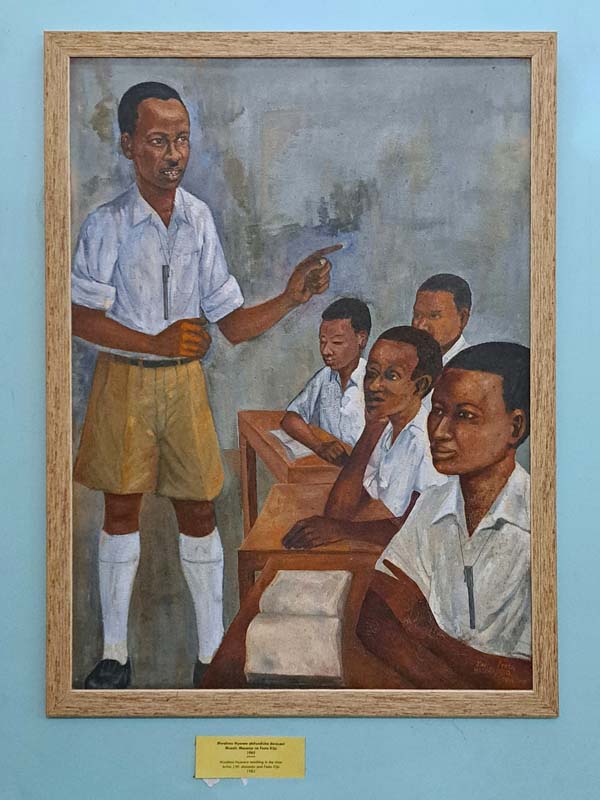

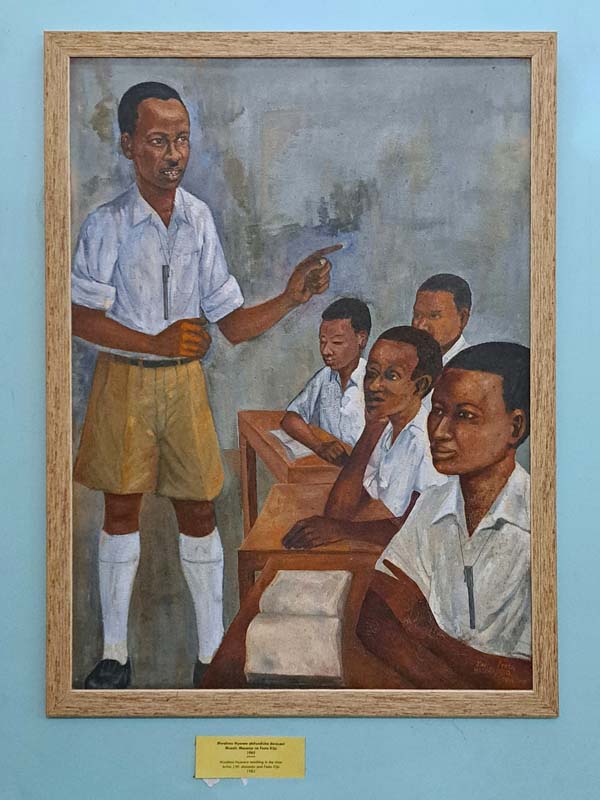

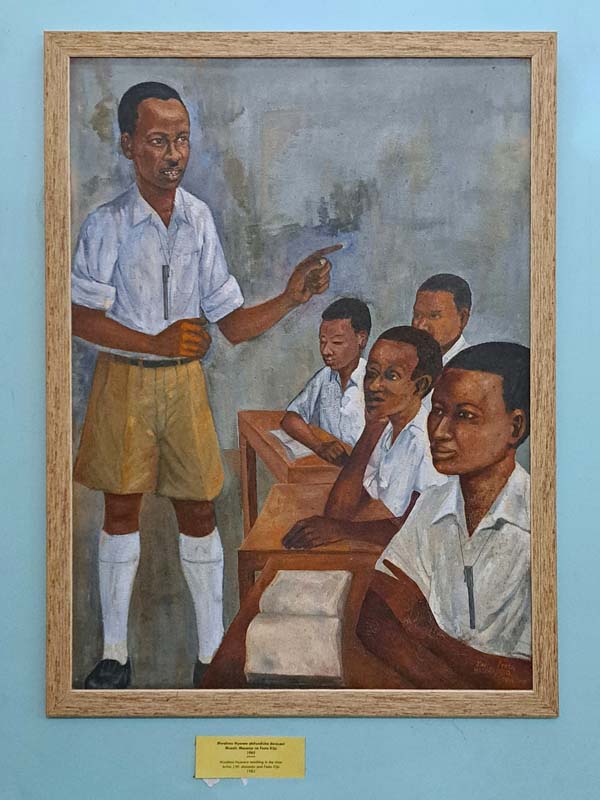

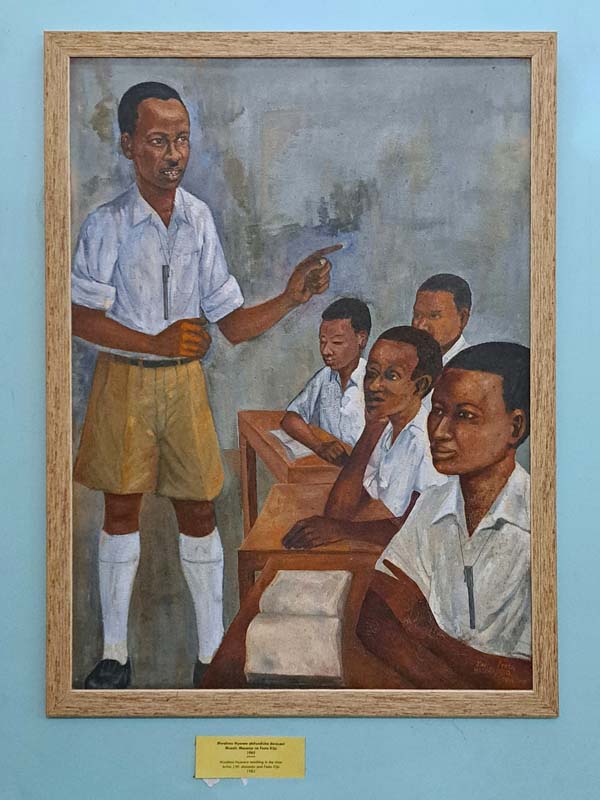

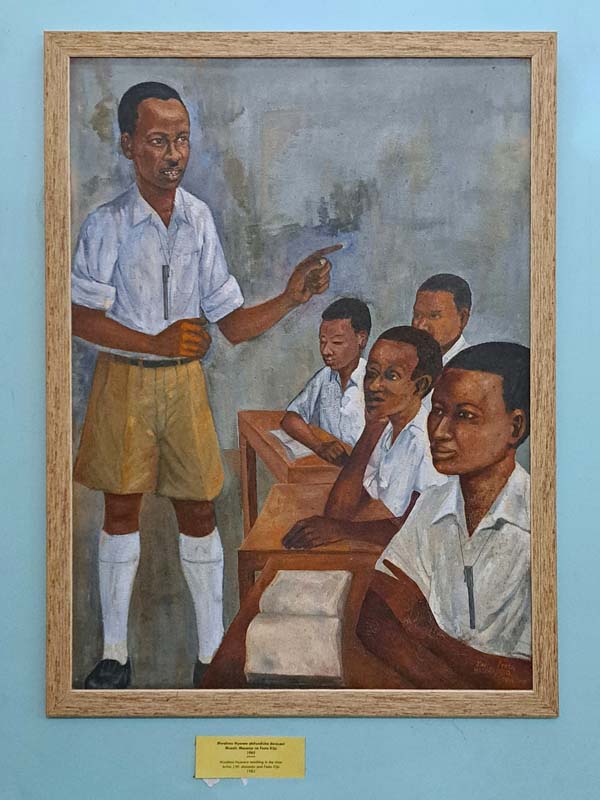

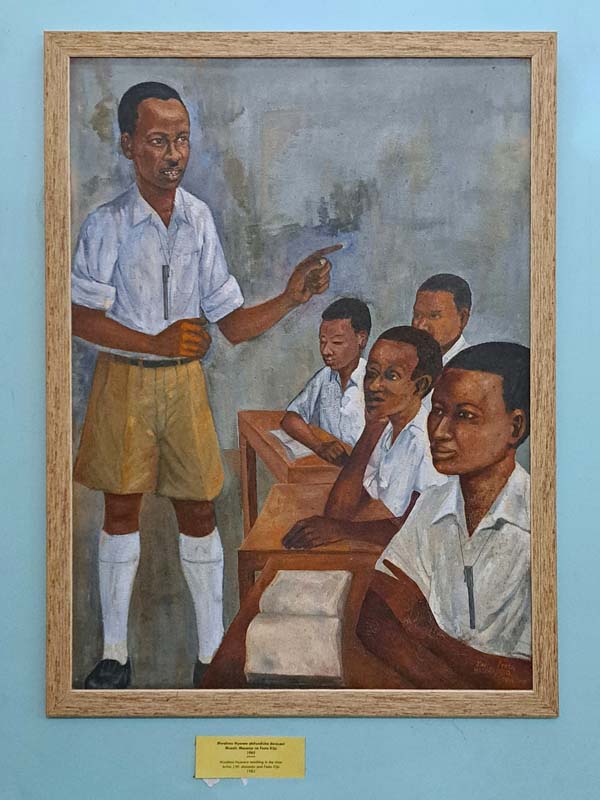

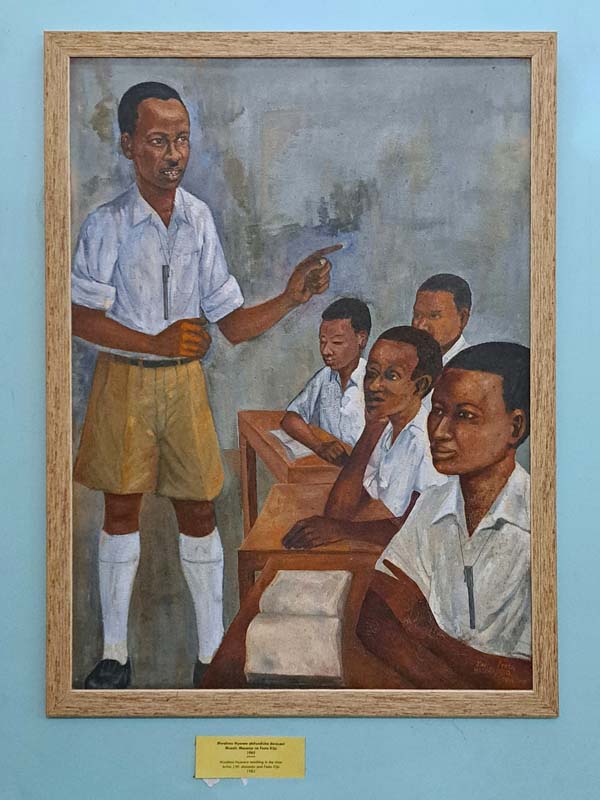

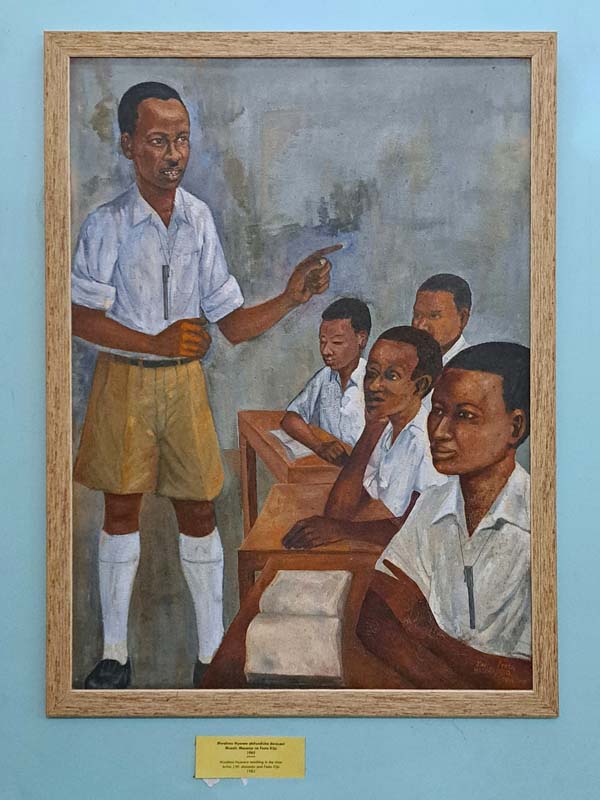

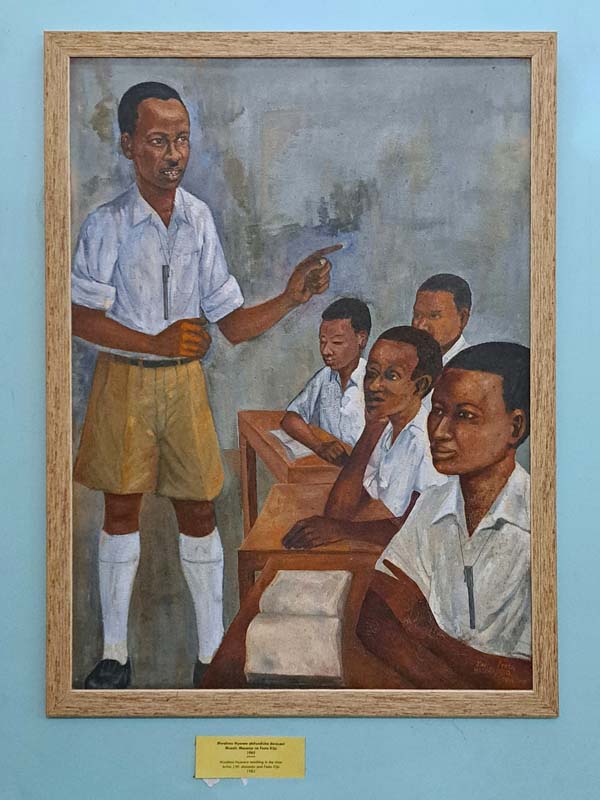

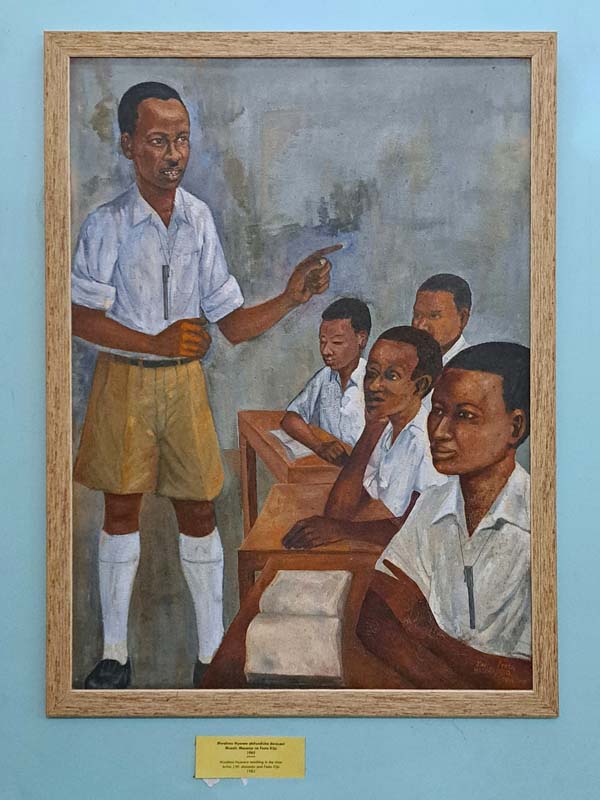

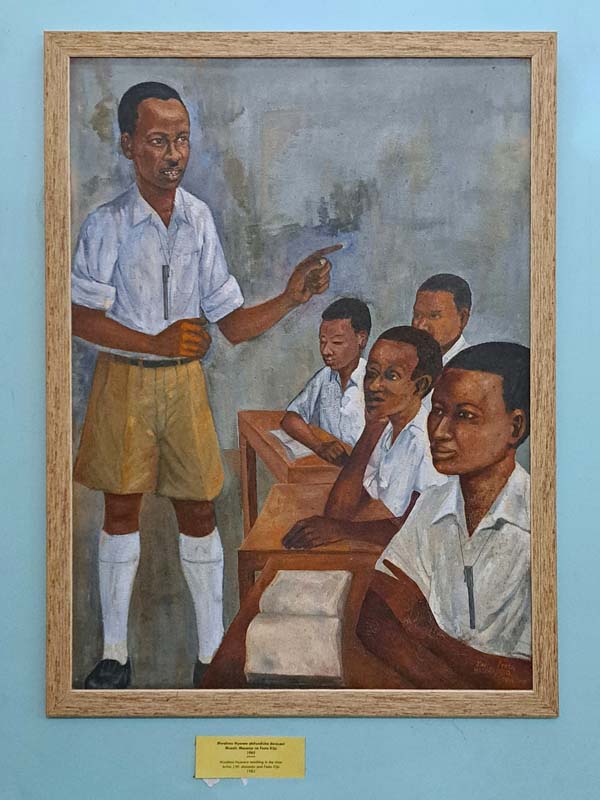

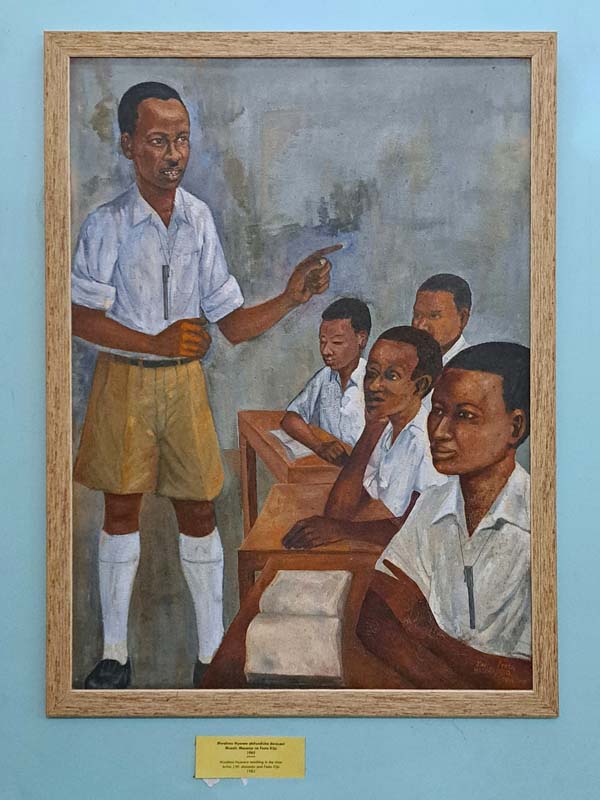

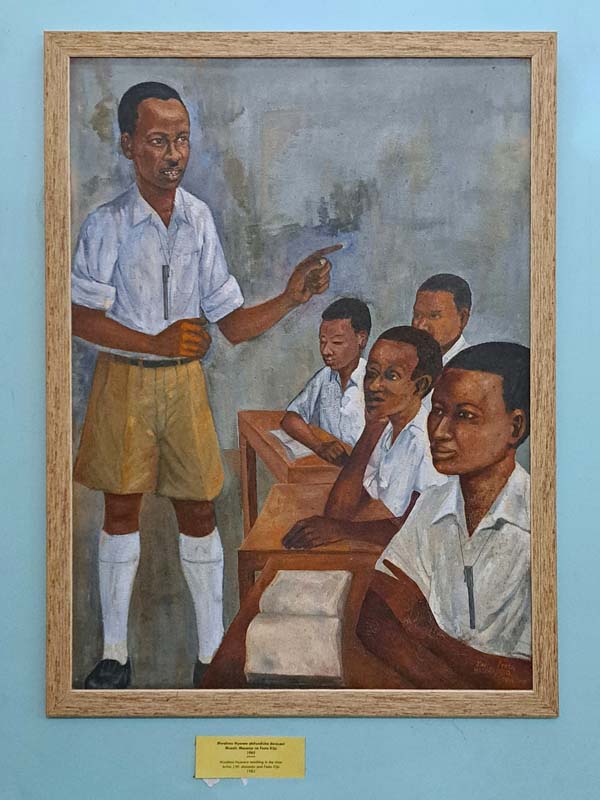

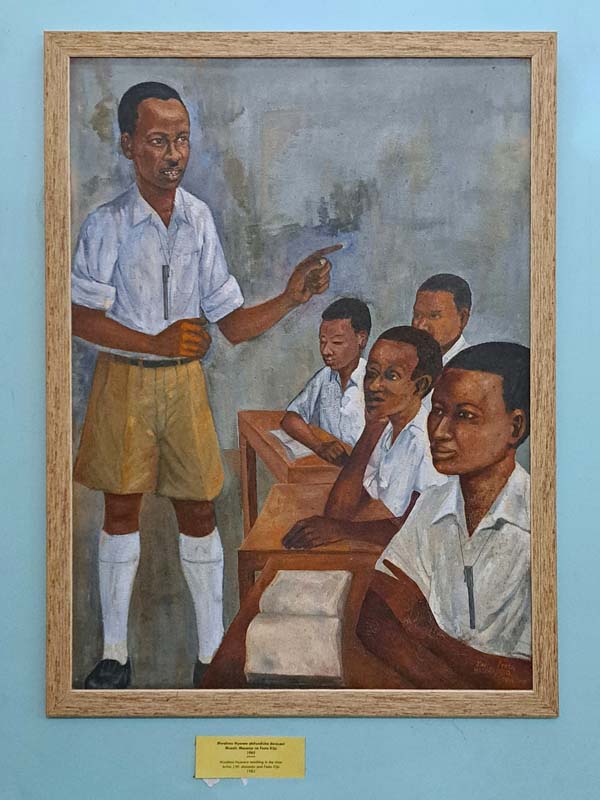

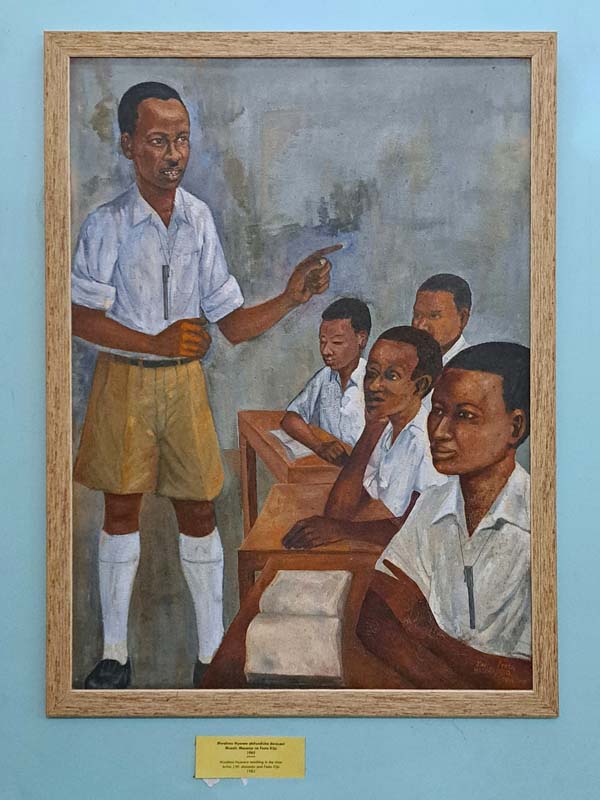

Painting by John Masanja and Festo Kijo: Mwalimu Nyerere teaches a class

He takes us to visit the University of Dar es Salaam campus, where he teaches. The campus is large, with buildings spread across a hilly green landscape. It is named after 'Mwalimu' Nyerere, whose role in postcolonial African history is highlighted especially by placing him alongside other key figures of the Pan-Africanist movement. Among them is Kwame Nkrumah, perhaps the most representative figure of this movement, after whom the main conference hall on the campus is dedicated. Like Nyerere, Nkrumah was the last Prime Minister of his country, modern-day Ghana, under colonial rule and the first President after independence.

In the National Museum, a large part of the paintings and photos in the gallery are dedicated to Nyerere. These range from conventional portraits to less common depictions of him as a teacher, in military attire during the Uganda-Tanzania war of the late 1970s, or meeting with local and foreign authorities. In Dodoma, the political capital of Tanzania, what seems to be the only true square, at least in the traditionally European sense of the term, is dedicated to him. His statue, raising the ceremonial baton, stands on a white marble pedestal at the center of the open space, surrounded by greenery.

In Tanzania, cities, campuses, and museums celebrate the father of the nation with monuments, paintings, public buildings, and squares. But for Nyerere, and to a large extent for the international bodies that supported his postcolonial policies, the future of Tanzania was largely to be found in transforming the countryside.

The Nkrumah Hall in the campus of the ‘Mwalimu Nyerere’ Dar es Salaam University.

Detail of the drain and the collection basin. In the background, the chemistry department.

Half London

‘Half London’ or ‘Londoni’, in Kongwa, a town along the Dar es Salaam-Dodoma bus route, might be a strange place to begin telling the recent history of Tanzania’s development and of the belief that the answers to its future would come from its peasant communities. Writing about a visit he made there in 1982, Nicholas Westcott, Professor of Practice in the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS University of London, recalls the neighbourhood as a ghost town:

“Empty concrete platforms lay among the thorn bush, steps leading up to emptiness, where a long-vanished veranda used to stand. A waterless washbasin stood alone on one. A small overgrown roundabout in the middle of nowhere had one or two barely legible road signs: ‘Piccadilly’, ‘The Strand’ … and a small stretch of tarmac ran 30 yards from each of the turnings until it petered out into sandy track.” [1]

More than forty years after Westcott visit, even less remains. The only visible traces that seem to have survived the passage of time and the inattention of the inhabitants of Kongwa, are the remnants of the old Overseas Food Corporation headquarters, now part of a school complex.

Still from the colour film 'The Groundnut Scheme at Kongwa Tanganyika', 1948. TR 17RAN PH6/49. University of Reading. https://vrr.reading.ac.uk/records/TR_17RAN_PH6/49

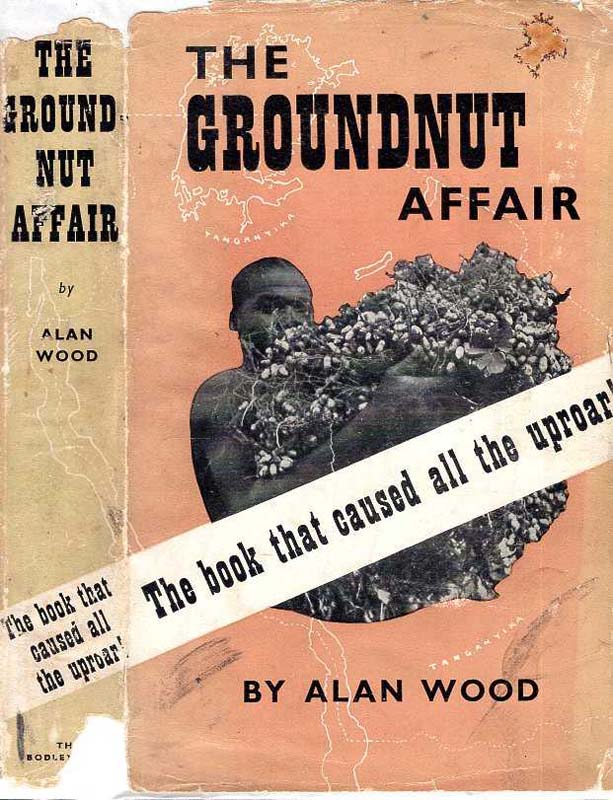

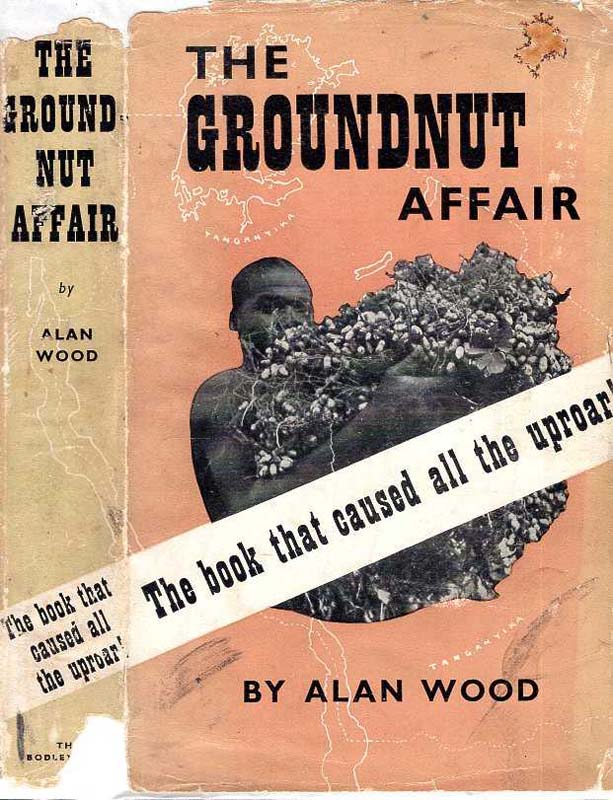

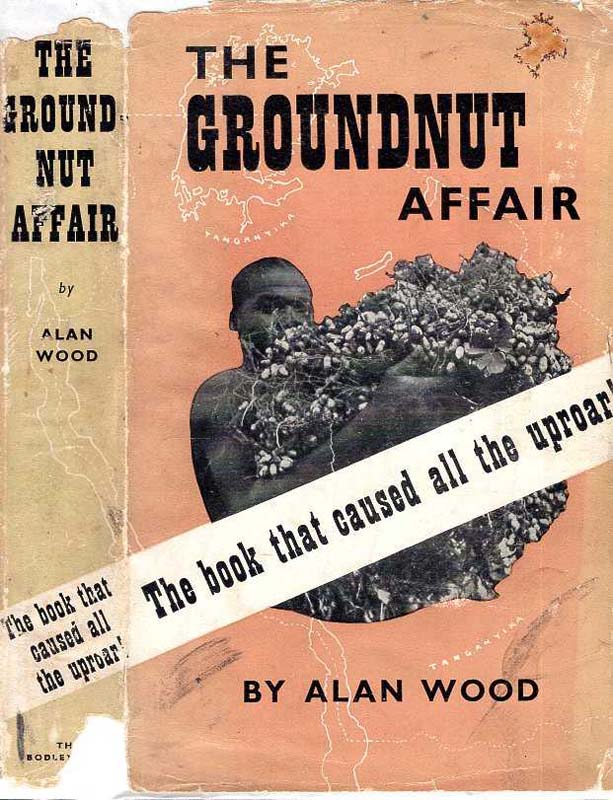

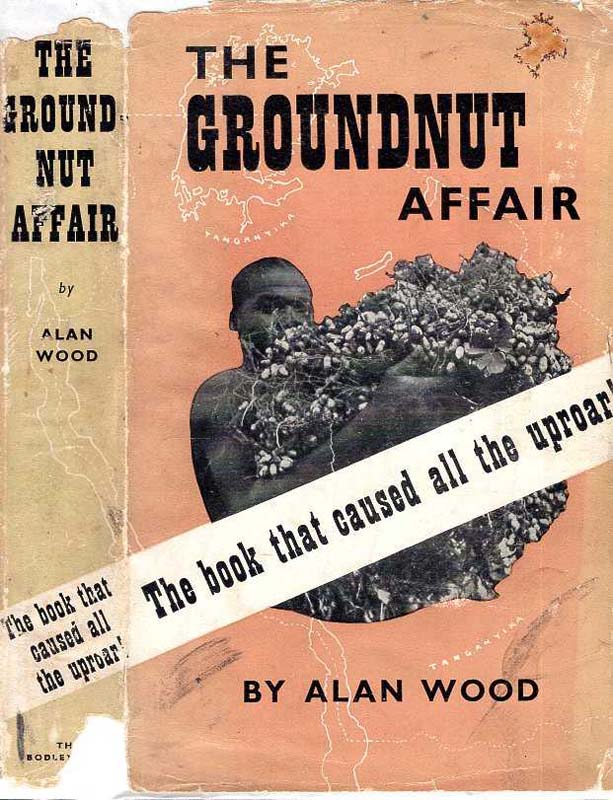

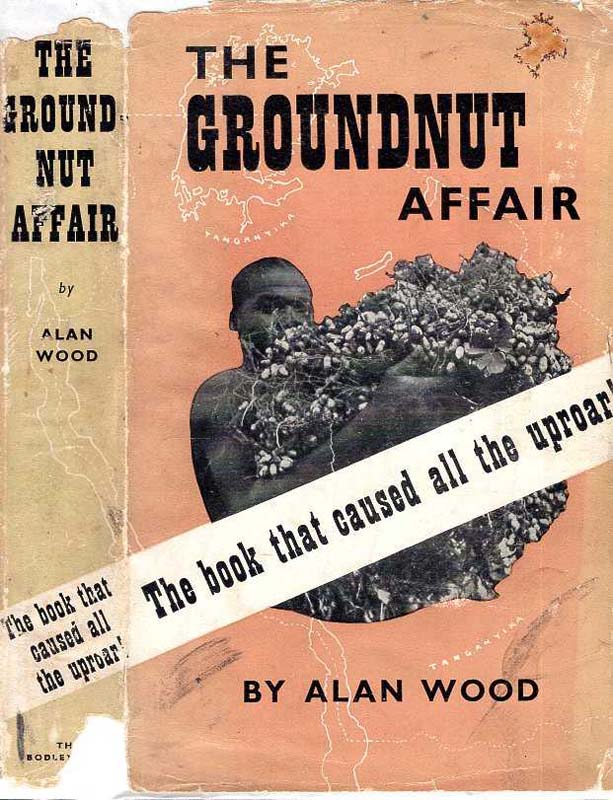

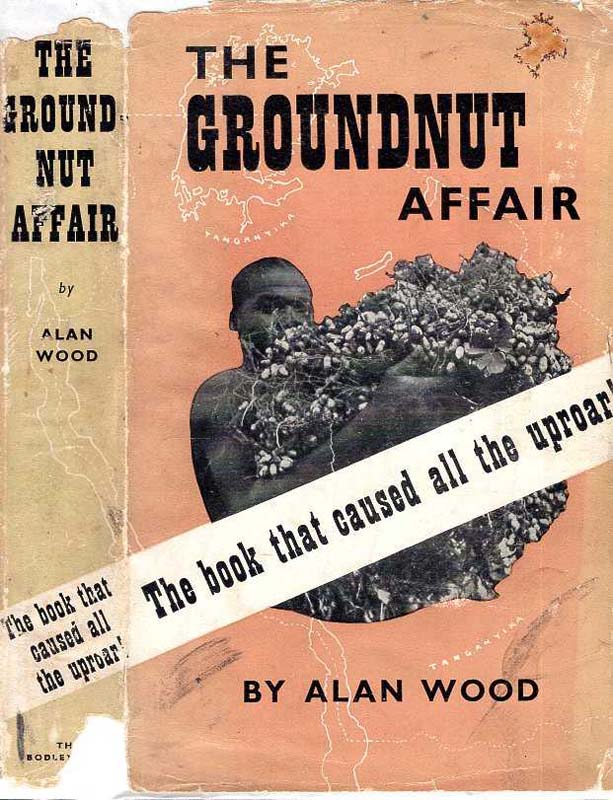

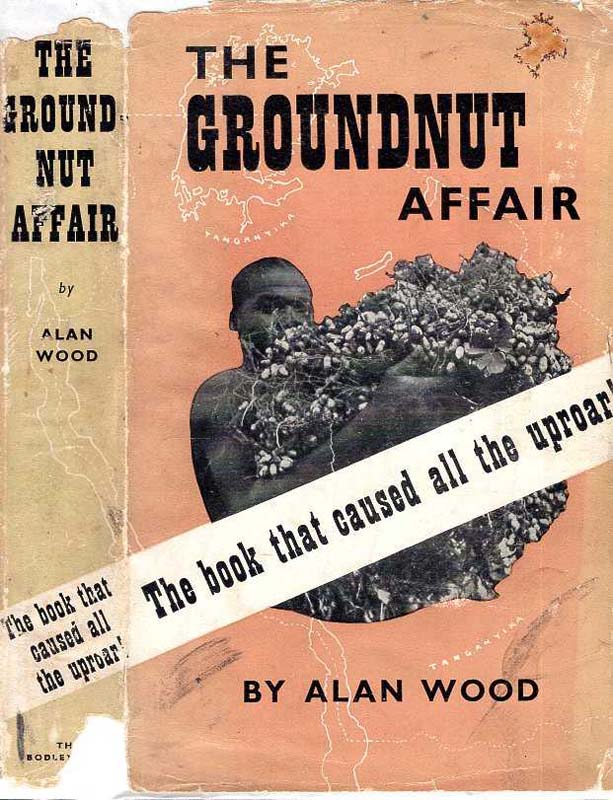

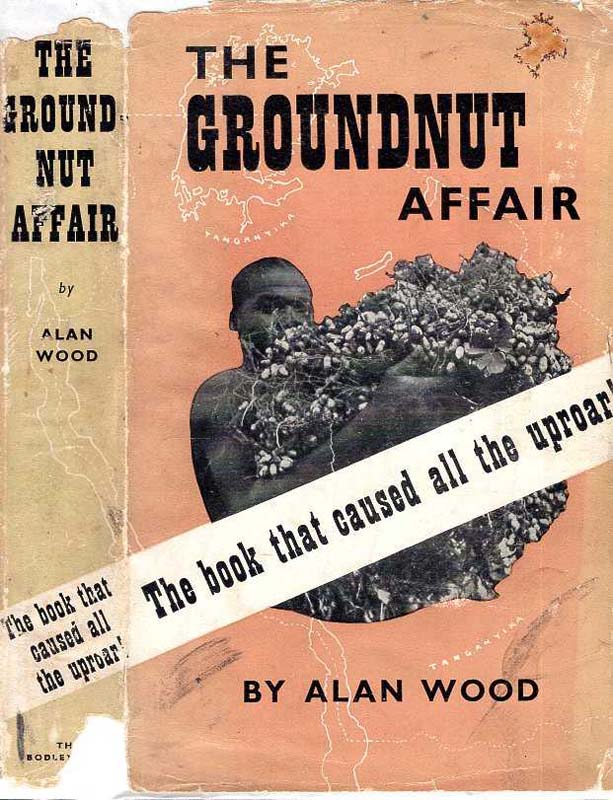

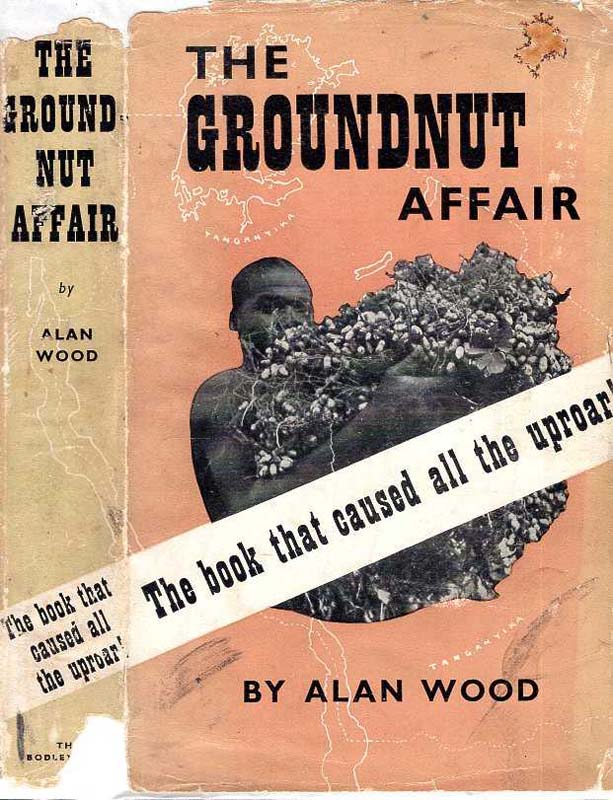

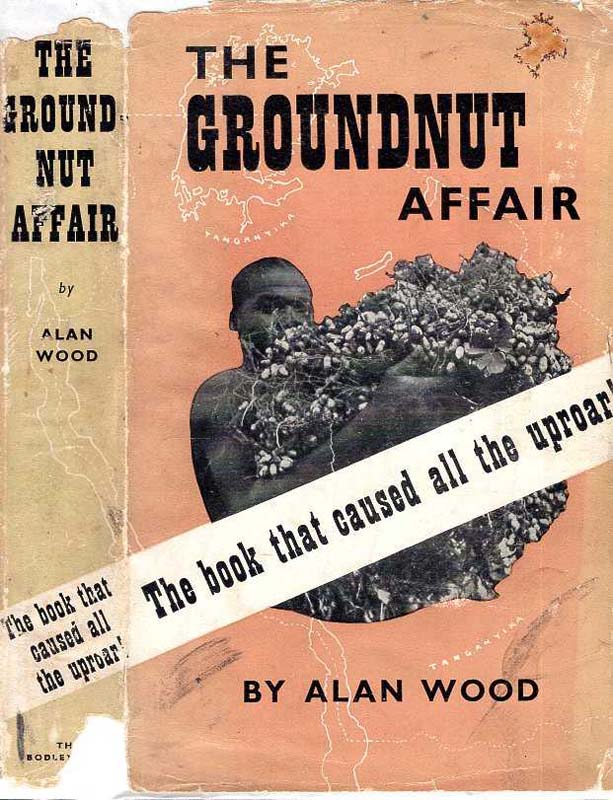

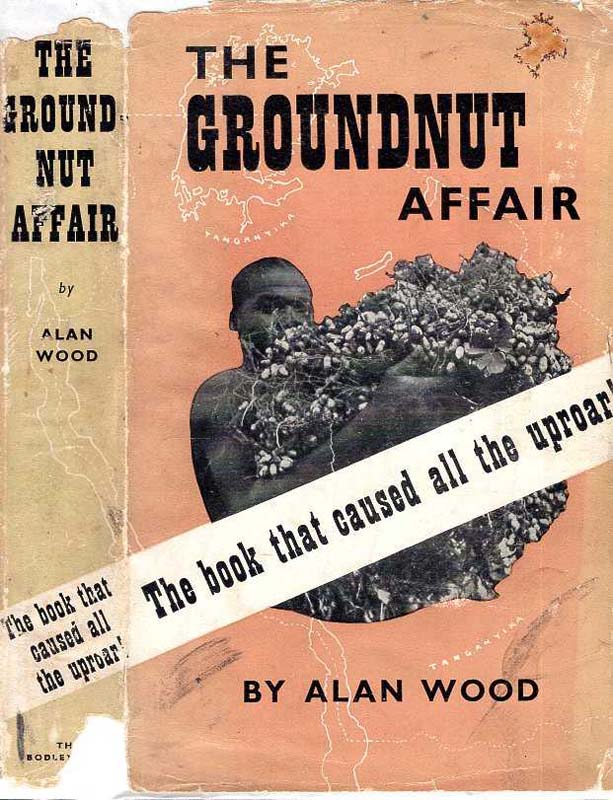

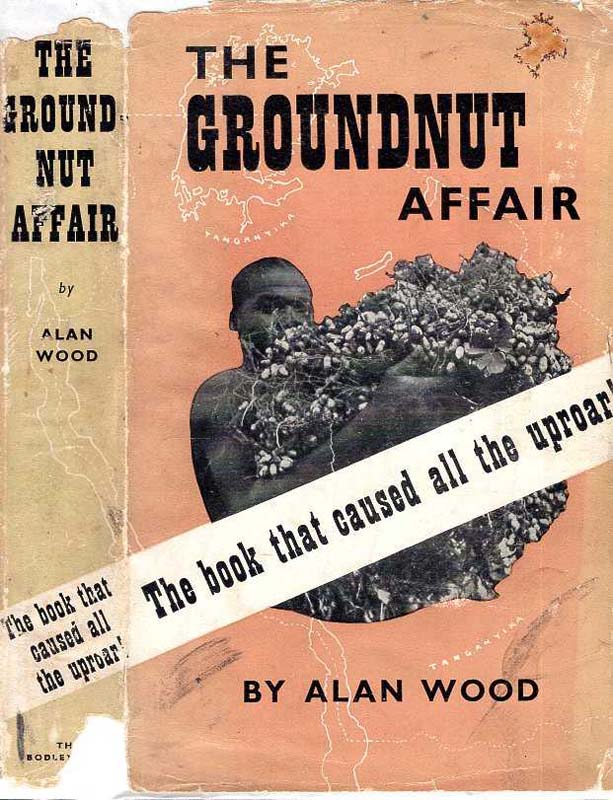

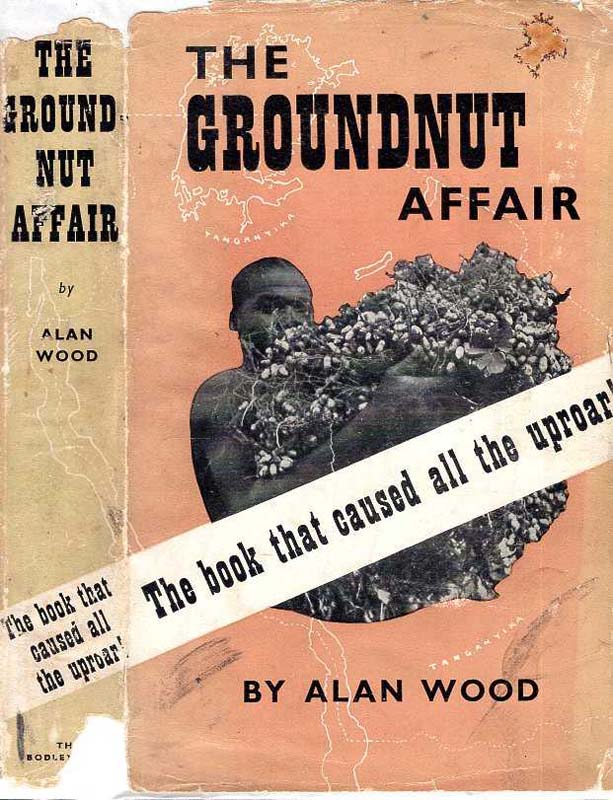

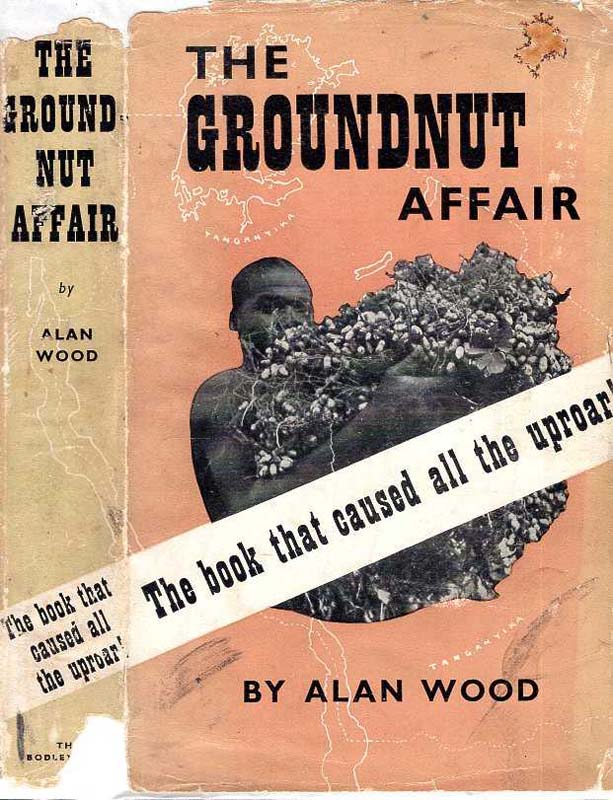

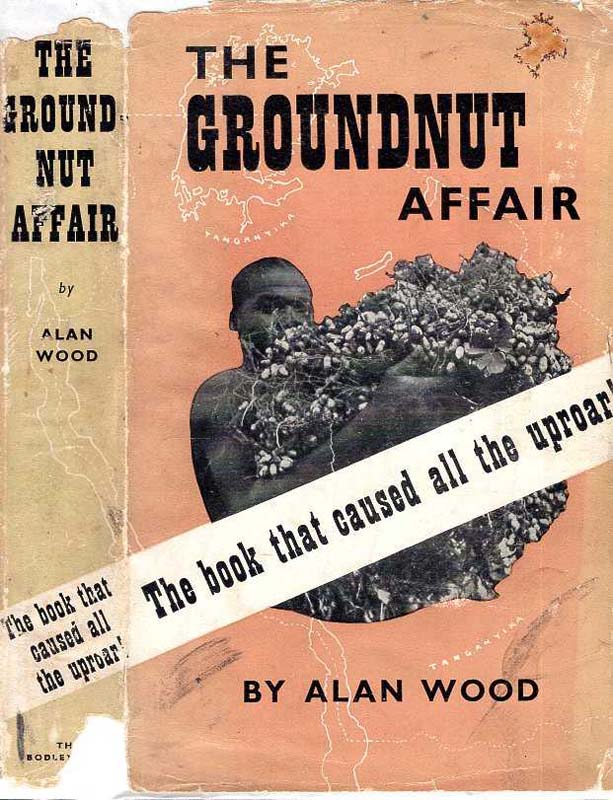

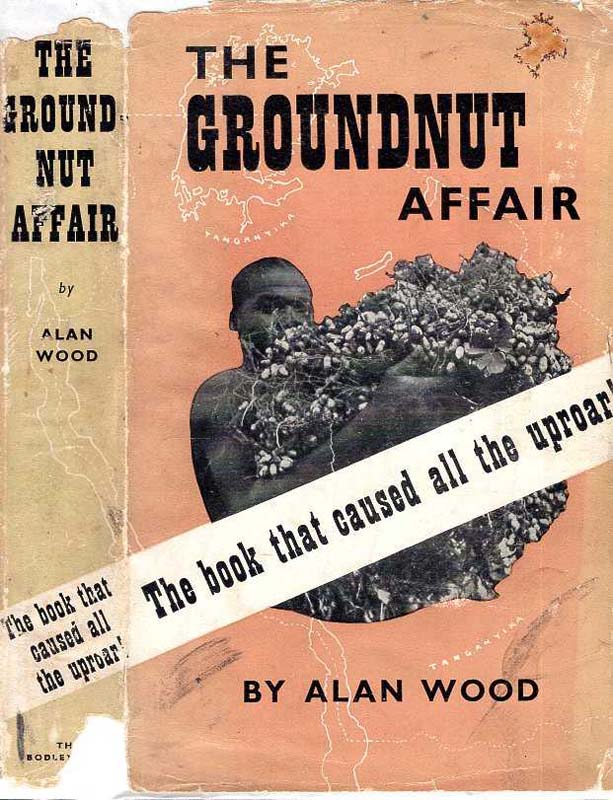

Book cover of ‘The groundnut affair’ by Alan Wood, one of the many publications recounting the story of a scheme that became a widely known symbol of the failure of late colonial aspirations.

That ‘the Overseas’, as it is remembered in Westcott's brief notes, and its most direct predecessor, the Groundnut Scheme, have not left an indelible mark on the collective memory of Tanzanians is confirmed by the fact that none of the people I spoke to during these weeks of travel had ever heard of it. Yet, among specialists in recent African history, the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme, inaugurated in 1946 and abandoned five years later, is without doubt one of the most famous development programs of the late British colonial period.

The scheme was a joint venture between the United African Company, a subsidiary of Unilever, and the colonial state and was one of the largest of this kind in history. It aimed to cultivate vast areas of land in modern-day Tanzania to produce groundnuts (peanuts), which were intended to help alleviate post-war food shortages and provide raw materials for the British food and oil industries. The scheme is famous among development experts and historians mainly for two reasons: Its enormous financial and geographical scale—occupying 1.2 million-hectares and costing the equivalent of £1 billion today, five times the total annual budget of the Tanganyika Administration—and the equally proportionate scale of its fiasco.

It is precisely its reputation as a cautionary tale of how large-scale development projects can fail due to poor planning, lack of understanding of local conditions, and logistical challenges that drives me to follow its traces. Failures, especially when they mark an era of development policies, like the Groundnut Scheme, may leave fewer obvious traces, but that does not make them any less significant. Its legacy in the political and environmental history of Tanzania goes beyond the often-tenuous connection to the physical sites of the project [2] and a curious place name lost in the arid highlands of Kongwa. As James Scott called it, the groundnut scheme was a ‘dress rehearsal’ for the even larger Tanzanian 'villagization' campaign in the 1970s. [3]

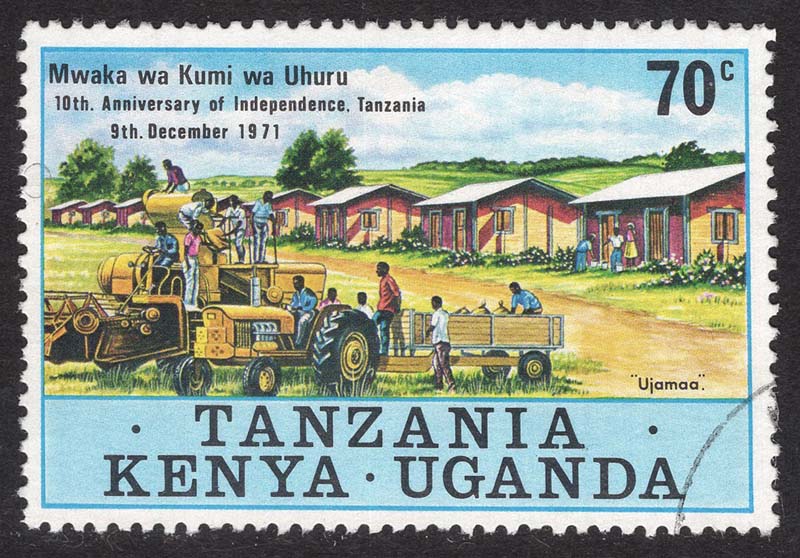

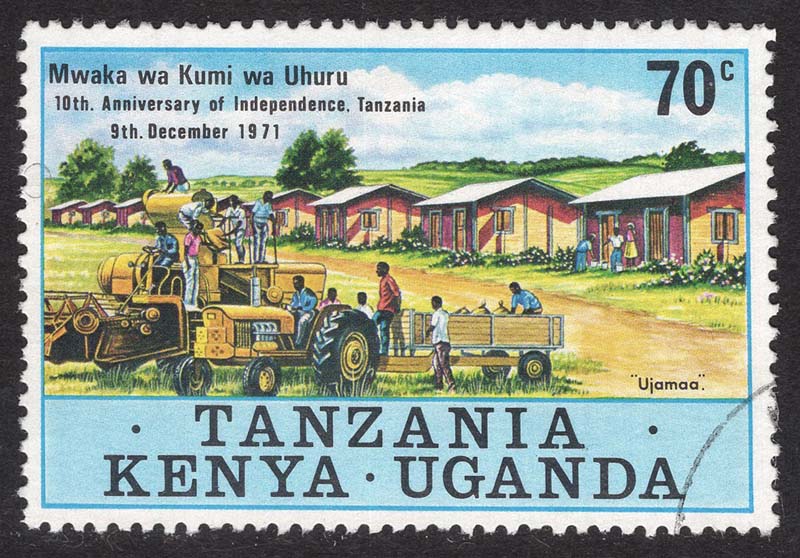

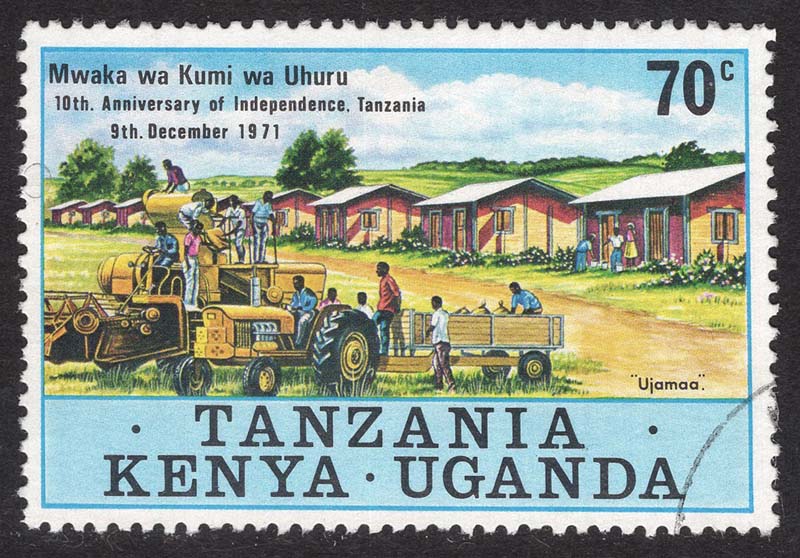

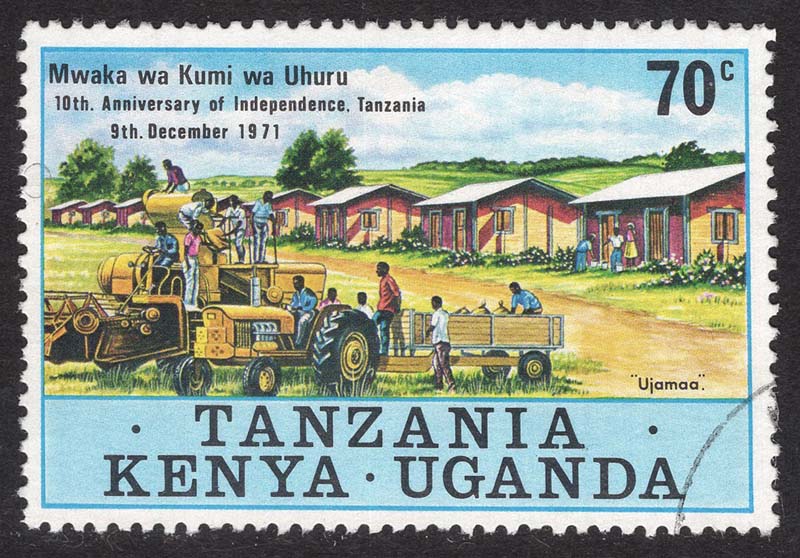

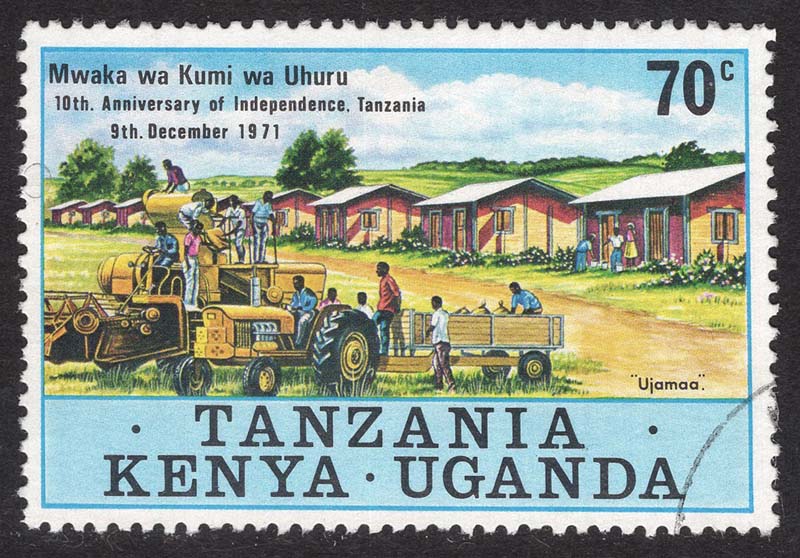

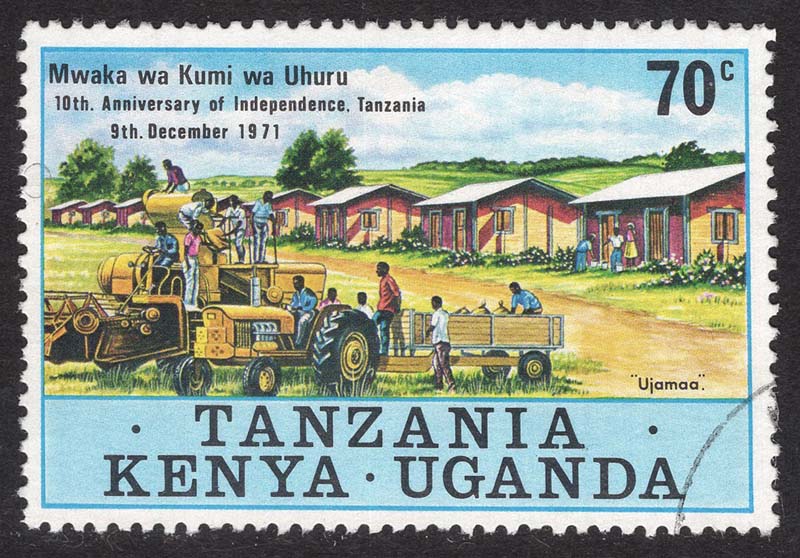

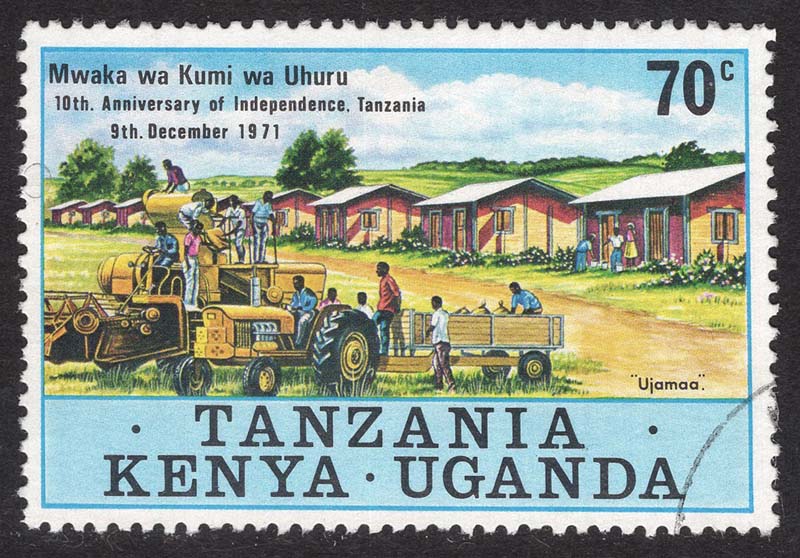

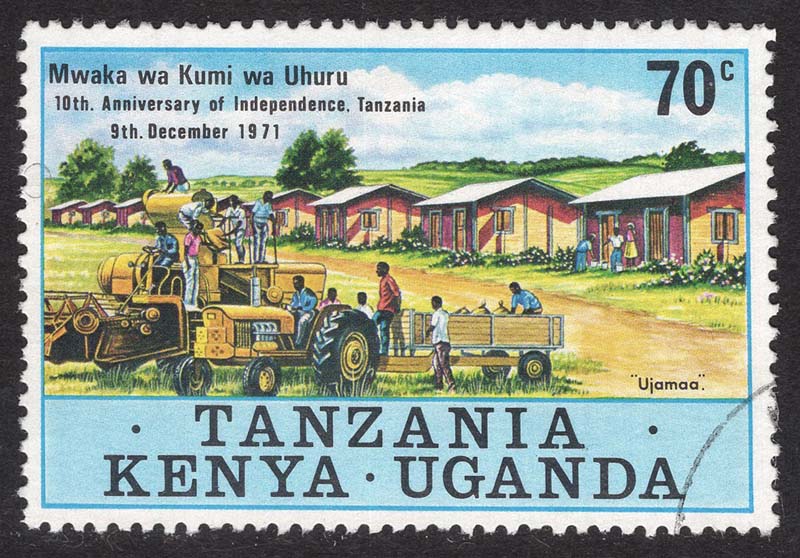

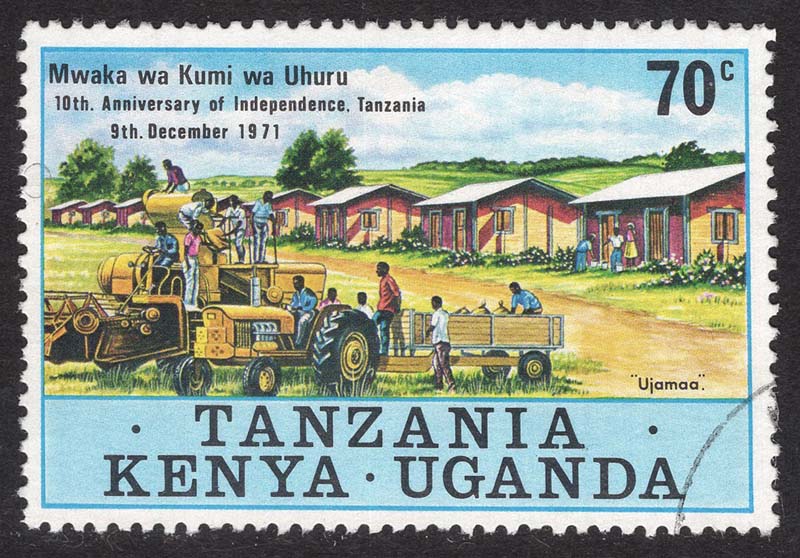

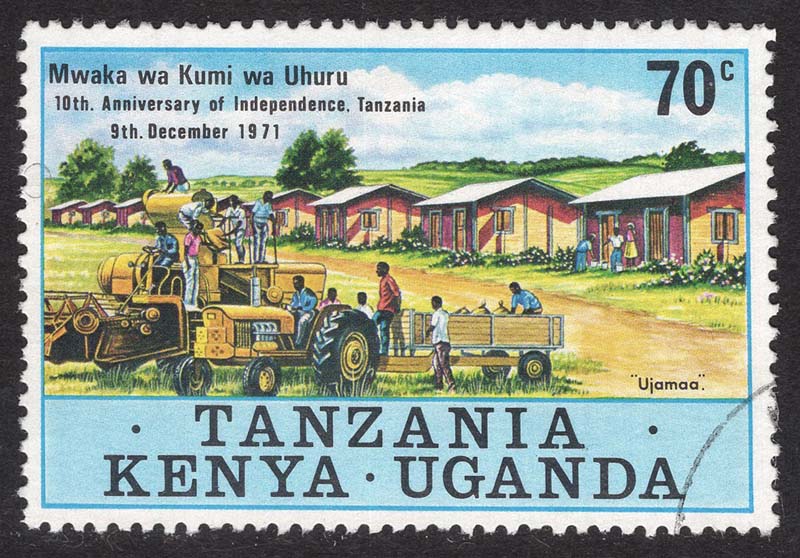

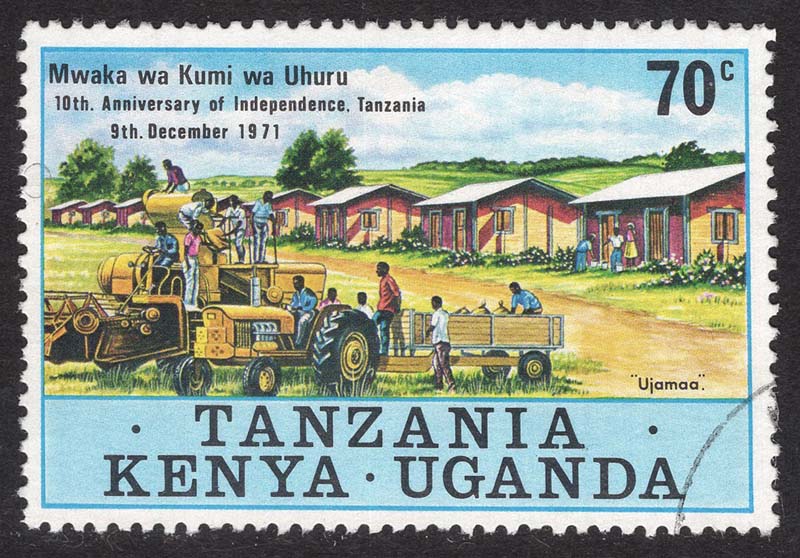

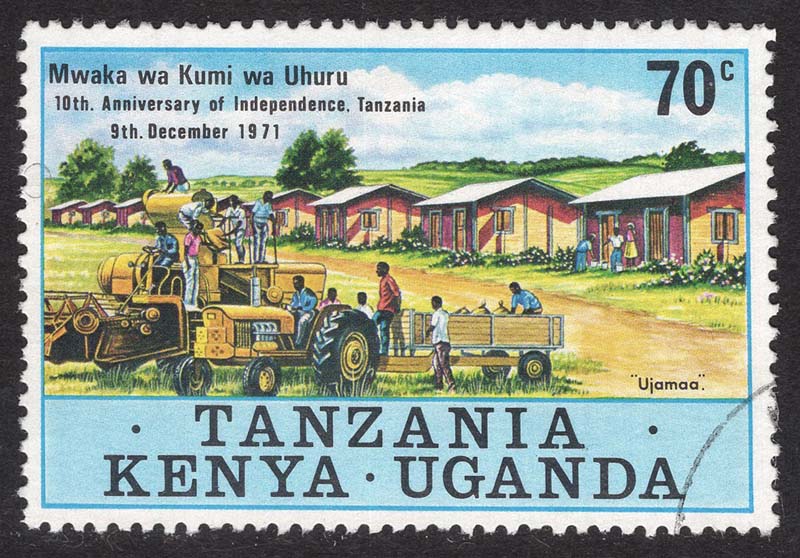

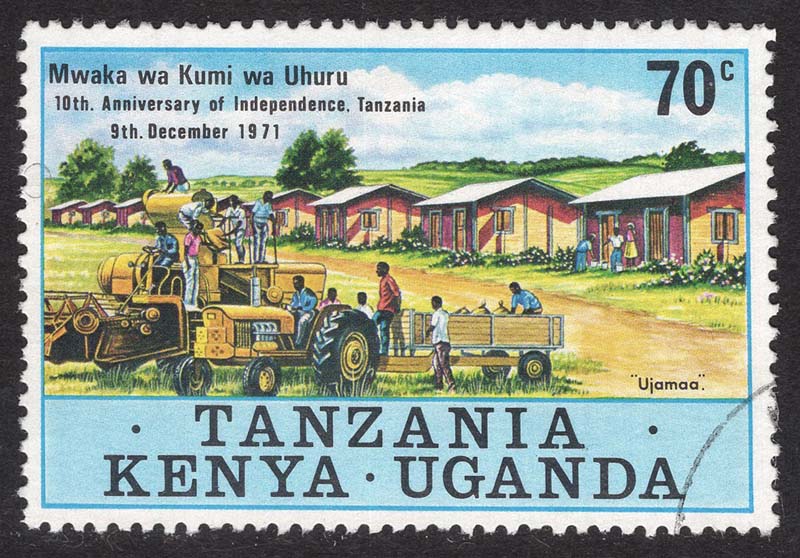

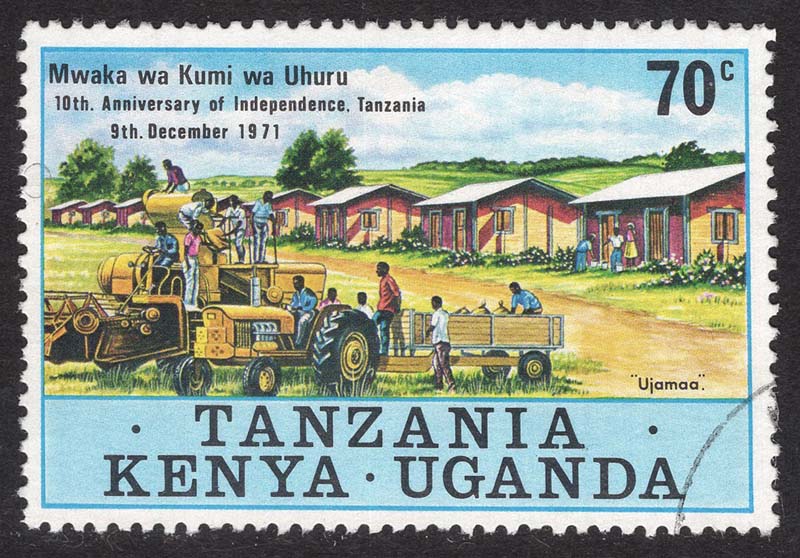

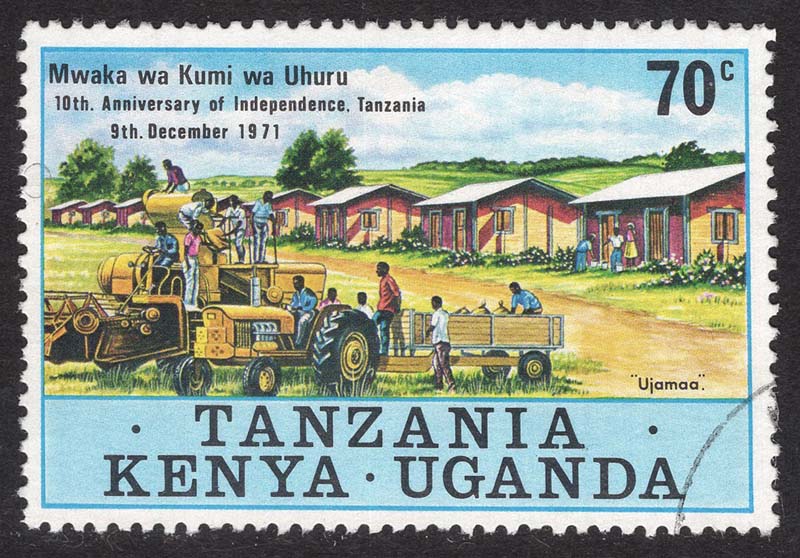

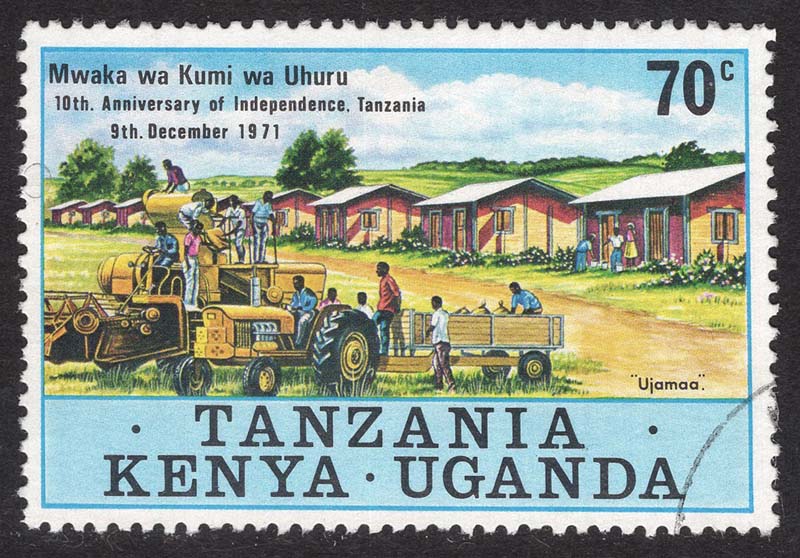

Ujamaa village stamp commemorating Tanzania 10th anniversary of Independence.

Ujamaa

Mabwe Pande and Kerege settlements lie both in a slightly hilly area not far from the coast. Neither settlement appears to have a central node. They spread out with low density over a relatively large area considering the limited number of inhabitants, with single-family home lots interspersed with small plots for cultivation and the larger compounds hosting schools, hospitals, and churches. The main difference between the two is that Kerege is traversed by a busy national road crowded with heavily loaded trucks and the ubiquitous dala dala—minibuses that are the primary public transportation system in the country. Mabwe Pande, instead, is located a few kilometers away from the same road and is reached by a dirt road ending at the protected natural area of Pande Game Reserve. According to Mabwe Pande’s inhabitants, the village is becoming increasingly popular destination for residents of Dar es Salaam seeking refuge from the city's congestion.

Even a trained eye would struggle to recognize any specific features or deduce the origins of these two settlements without a local guide. In Kerege, before being accompanied by one of its original inhabitants, who moved there with his family at the time of its founding in the 1960s, we go through the extremely cordial, and equally verbose, procedures of party bureaucracy. The same party founded by Nyerere, one of the longest-ruling parties in Africa.

Kerege and Mabwe Pande are two of the thousands of villages (estimates of the total number vary depending on classifications and the various phases of implementation) founded in Tanzania between the 1960s and the mid-1980s. They were created as part of a villagization policy aimed at transforming rural society by resettling scattered rural populations into planned villages known as Ujamaa villages. This policy was a cornerstone of Nyerere's broader Ujamaa socialist ideology, intending to foster collective agriculture, communal living, and social cohesion among rural communities.

“The growth of village life will help us in improving our system of democratic government,” Nyerere declared in his inaugural presidential speech in 1962. “I intend first to set up a new department: the Department of Development Planning. This Department will be directly under my control, and it will make every effort to prepare plans for village development for the whole country as quickly as possible.”

The school in Mabwe Pande.

A water tank in the school courtyard.

The old dispensary, now adjacent to a new building, is currently used as a warehouse.

Visiting the two villages confirms what archives and publications initially suggested. Kerege was one of the pilot projects used to test and showcase the Ujamaa village concept to foreign authorities as evidence of the success of rural socialization in the country. Residents recall frequent visits in the 1970s by Chinese, Russian, and Western officials due to its proximity to Dar es Salaam and its location along a major transport route. This explains both the vividness with which its history is recounted by its inhabitants and the material traces that remain. The village focused on cashew nut production, and some of the houses built for its residents within a 2.5-kilometer radius of the village center are still extant, along with rows of houses for the ‘experts’ and some infrastructure built with contributions from village members.

In contrast, Mabwe Pande’s lack of a representative role makes public intervention less noticeable, which seems to affect how its history is remembered by its residents. Or perhaps the absence of party representatives makes people more willing to share its history in less one-sidedly positive terms. As one resident recounts, when village construction began in 1964, those already living within the designated area were allowed to stay. However, other cooperative members were brought in from nearby lands and were forced to leave their owned and cultivated land to move to the new center.

“They were given half an acre of land to build their own house and for a vegetable garden." The cotton farm where everyone worked, instead, remained outside the village”.

Kerege: one of the “experts’ houses” with the green flag of the Party of the Revolution.

A now-closed shop window surreptitiously opened into a wall. The only shop in Kerege while the Ujamaa program was active had been converted from one of the communal storage warehouses in the center of the village.

Chief village in a nation of villages

We missed the inauguration of the first electric passenger train connecting Dar es Salaam with Tanzania's political capital, Dodoma, by just a few days. The railway line has existed since the days of German East Africa, but we are told, it has been virtually unused for a long time. Indeed, the traffic between the two cities is far from intense. Dodoma is not a tourist destination, and it has only recently begun to play a significant role as an administrative center following the transfer of some ministries. Despite being designated as the capital over 50 years ago, when Nyerere announced plans to shift the national capital from the coastal Dar es Salaam to a new city in the center of the country, Dodoma's development has been slow.

It is all too obvious to describe Dodoma as a quiet city. The landscape is a flat, semi-arid plateau covered with sparse vegetation, mostly acacia shrubs, and punctuated by scattered hills that rise abruptly from the flat terrain as if placed there by chance. Atop one of these hills, sits the residence of the head of state, which visually dominates the city. The city spreads horizontally, and even recent developments like the new university campus and the new decentralized railway station contribute to fragmented urban growth. Although the history of Dodoma's master plan is troubled and none of the many proposals have ever been fully completed, this weak urbanity, which contrasts to the cosmopolitan image of Dar es Salaam, is not surprising given the vision of the country's intellectual and political leaders in the post-independence era. As contradictory as it may sound, villagization inspired the single most relevant urban project that Tanzania underwent since independence.

Amidst a global movement for pan-African renaissance, as Emily Callaci brilliantly observed [4], Tanzanian nationalism reframed coastal urbanism as a symbol of foreign domination. The Dodoma plan promised a decolonized, genuinely African modern city envisioned not as another stratified and diverse city marked by a violent world history, but rather as a rural city, created and inhabited by peasants. While Ujamaa villagization aimed to establish new villages throughout the country, Dodoma was conceived, in Nyerere's words, as 'the chief village in a nation of villages’. [5]

The Dodoma Masterplan: the new capital city is conceived as a juxtaposition of villages.

Wandering through parts of Dodoma I believe, based on my attempts to match the 1976 master plan with satellite views, to have been built according to the original idea, I searched for the physical expression of the African authenticity advocated by the scheme’s proponents. The result is unexpected: Small clusters of houses arranged around large communal open spaces, winding roads, and houses set generously amid the vegetation.

Dodoma is one of the very few cities I have visited where you can literally walk from the city center to the airport. Beyond the airport strip lies a neighborhood whose layout resembles the one envisioned in the original master plan. As we walked through it, we came across two unusually large open spaces that serve as the public core of the neighborhood. Groups of boys are playing football, a few cows are grazing, and the silhouette of the hill where the new state house was built stands out in the background. Around these spaces, rows of houses arranged in various blocks are visible. I recognize some of the prototype houses designed by the Canadian firm ‘Project Planning Associates Limited’ (PPAL), which exhibit distinctly Western, if not North American, 1970s architecture. Between these blocks, the semi-public spaces are carefully designed to minimize the impact of cars. The more you explore this part of the city, the more it resembles a wealthy “suburbia.”

Residences designed by PPAL

The winding flowerbeds that border the parking spaces within the blocks.

Some of the houses are numbered with the initial CDA most probably meaning Capital Development Authority.

As Sophie van Ginneken notes [6], Dodoma is a weird assemblage. Given the socialist aims of the new capital city and Nyerere’s reliance on local rural tradition, it is fairly ironic that a Canadian office was asked to design the Dodoma master plan. But because of the choice made by Tanzanian authorities, it is not surprising that the final design borrowed from the American suburban planning model. The outcome of such combination reflects a blend of contrasting ideologies, compromises, and the practical challenges of implementation. The concrete realization of the 'weak urbanity' envisioned in the original plan—meant to exemplify an alternative, truly African approach to urban planning for a peasant class—is instead embodied by clusters of villas in neighborhood units, where Dodoma’s middle and upper classes live.

In this regard, Dodoma’s planning experience helps us piece together the fragments of this journey. If I started by telling this story from one of the most spectacular fiascos of late colonial history, Ujamaa villagization policy, not unlike the groundnut scheme, failed catastrophically. My perspective inevitably centers on the forced resettlement and the coercive practices used by the regime to support villagization, and the work of many has documented these testimonies [7]. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the policy faced significant challenges, including economic inefficiencies, resistance from rural communities, and administrative problems. The forced relocations disrupted traditional farming practices, and many villages struggled with inadequate resources and infrastructure. By the mid-1980s, the policy was gradually phased out in favour of strategies that better addressed economic realities and development needs.

Ironically, today, in its common usage, the word Ujamaa has lost much of its explicit connection to an ideological and governmental program. In Zanzibar and in Dar es Salaam, luxury resorts use the name to evoke a sense of cosiness, cordiality, and familiar comfort. The expression is mostly understood as a generic appeal to equality and solidarity. Just as the silhouette of famous Mount Kilimanjaro is a catchy Tanzanian symbol for tourists, so is Ujamaa. Yet, once again, I try not to remain blind to the wider impact these experiences have had on the way Tanzanians perceive themselves and their national identity. If one should remain sceptical to the often reductionist views of Africa as merely a ‘testing ground’ or ‘laboratory,’ Tanzanian history in the second half of the 20th century reminds us that failures, contradictions, and compromises are inherent in periods of transition. Even when they leave less evident traces, their legacy is significant to capture the full scope of national development and identity formation.

Mount Kilimajaro, a recognizable symbol of Tanzania, in a diner in Dodoma.

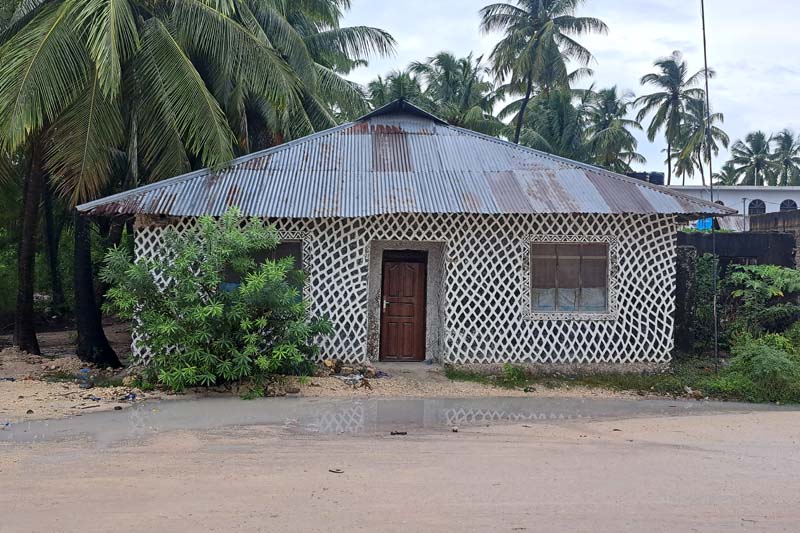

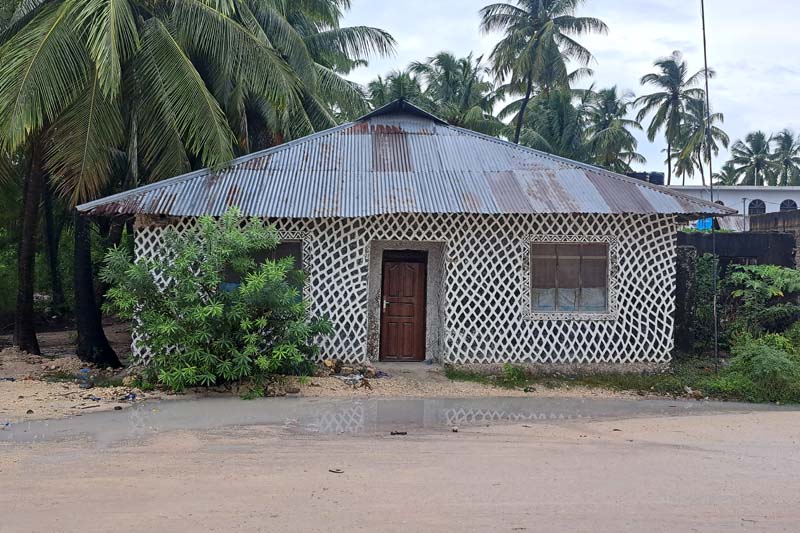

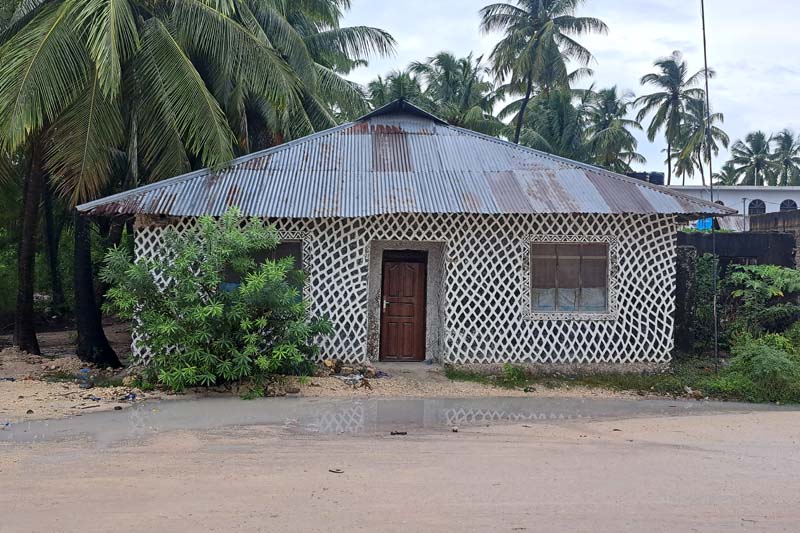

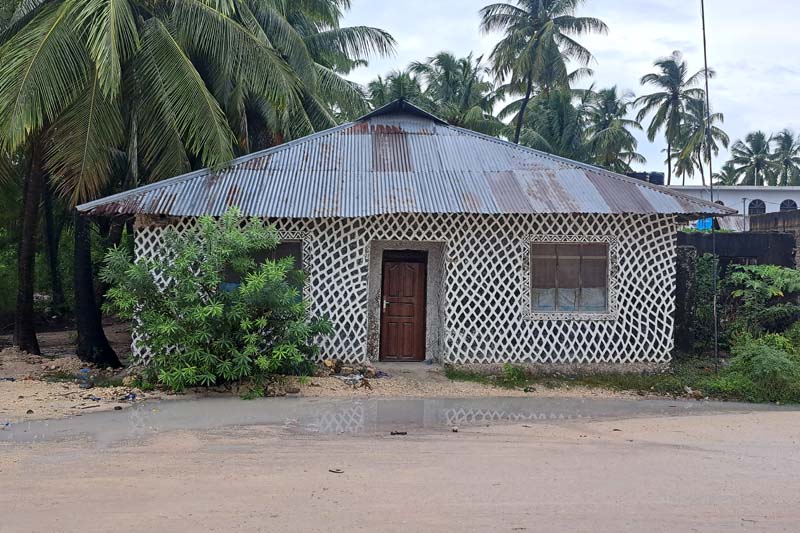

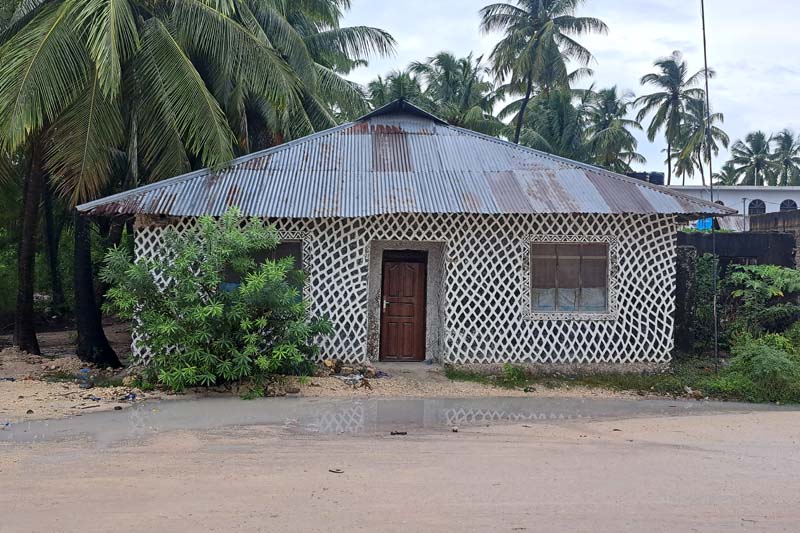

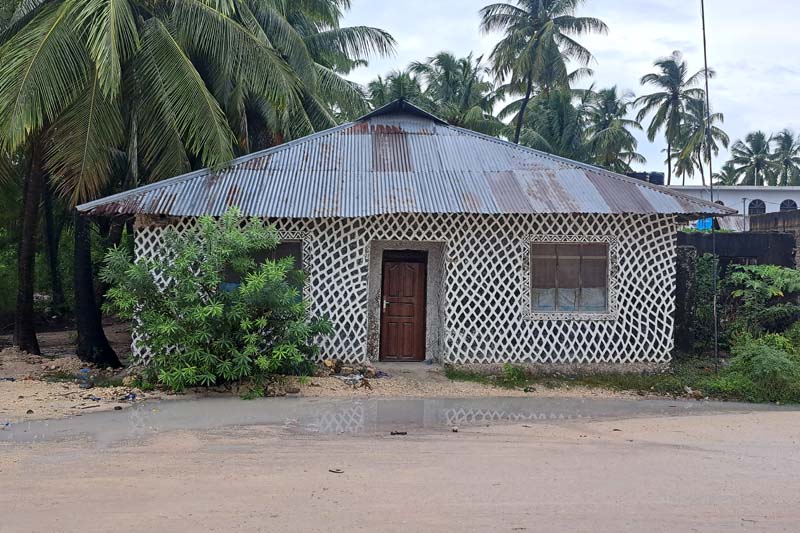

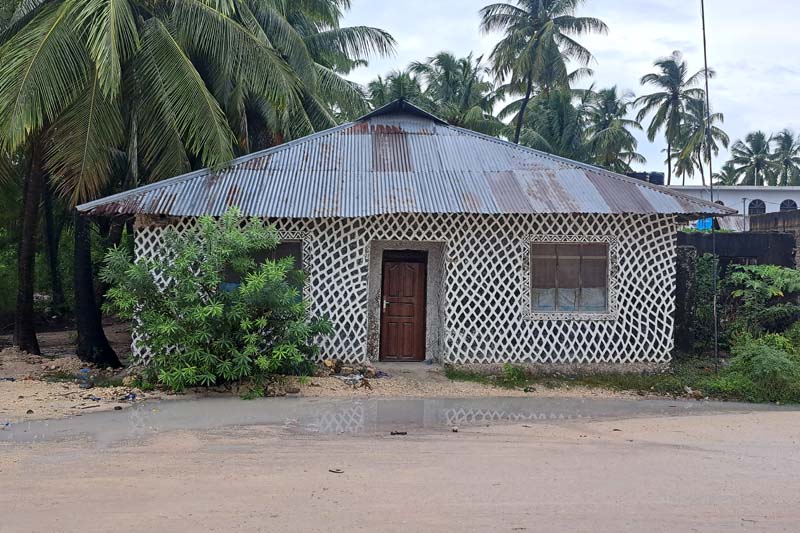

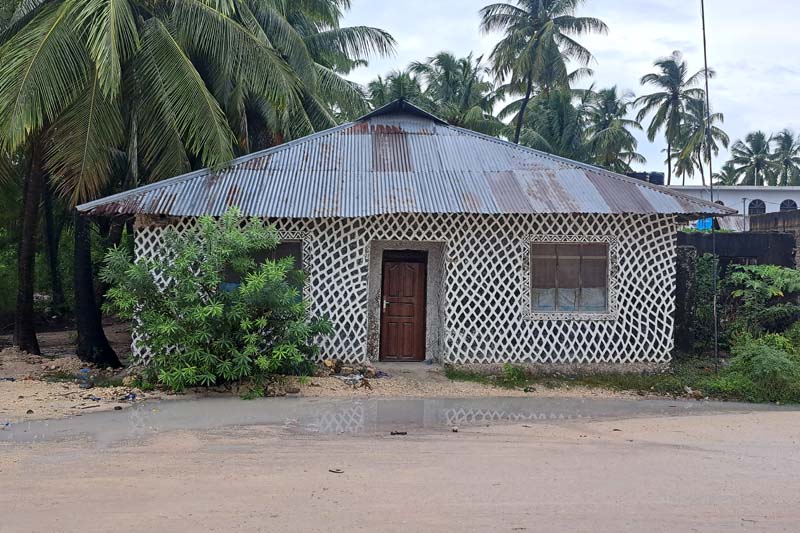

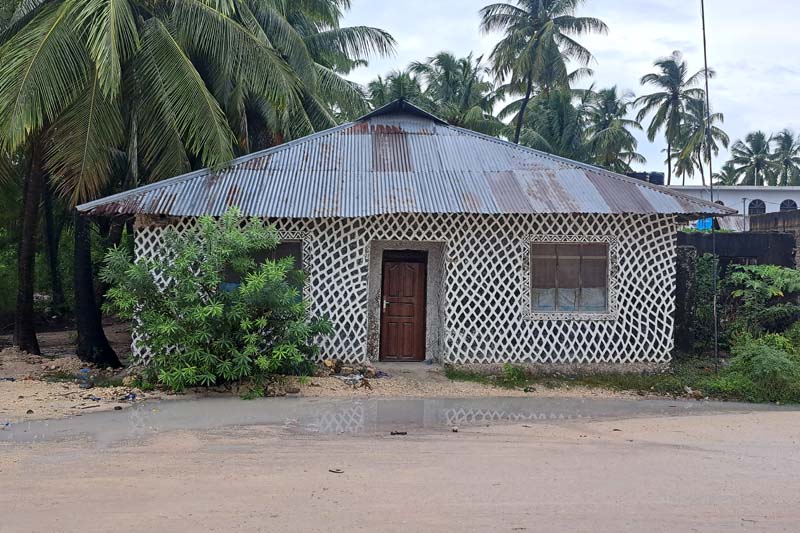

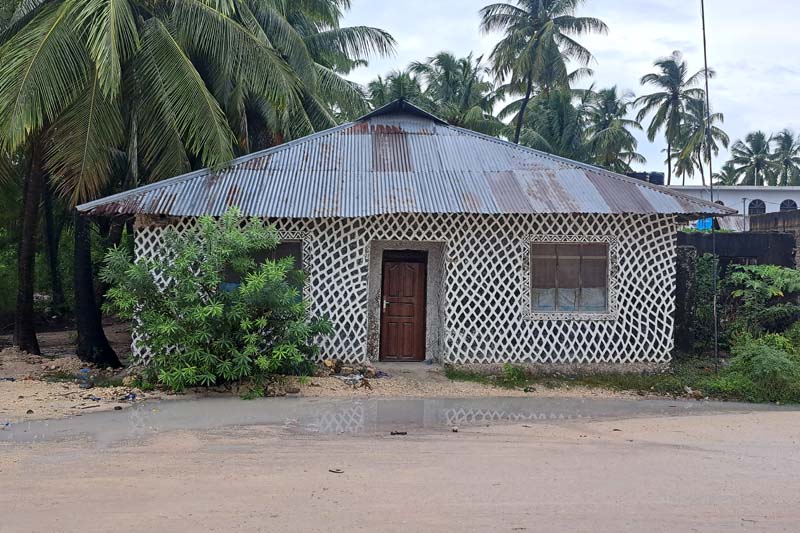

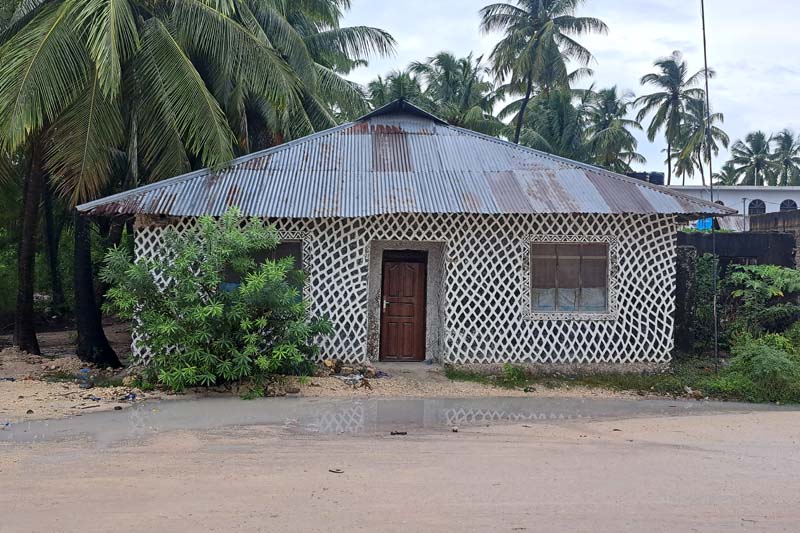

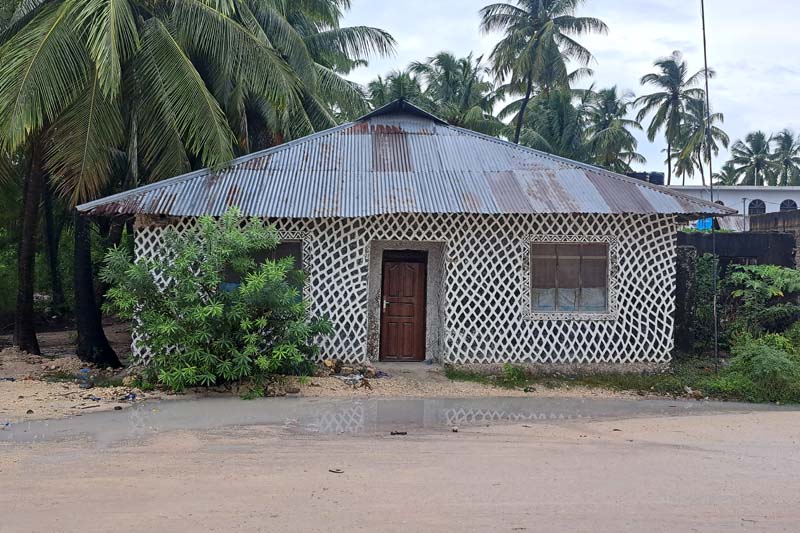

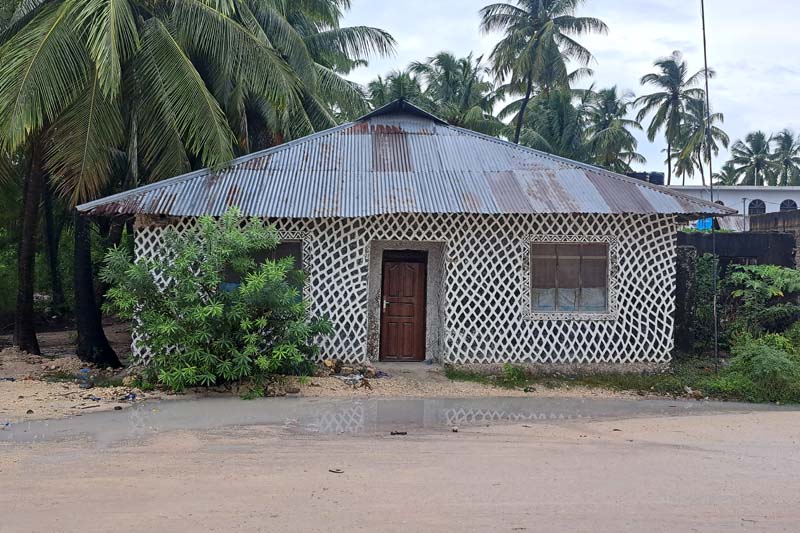

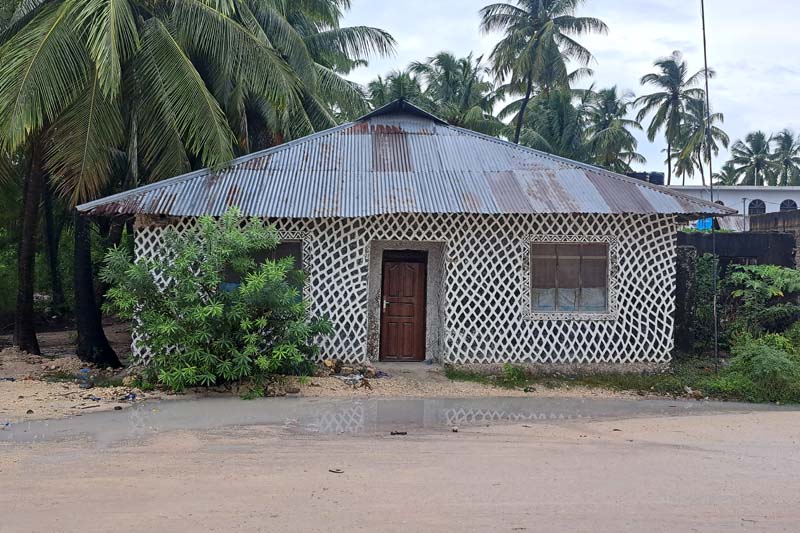

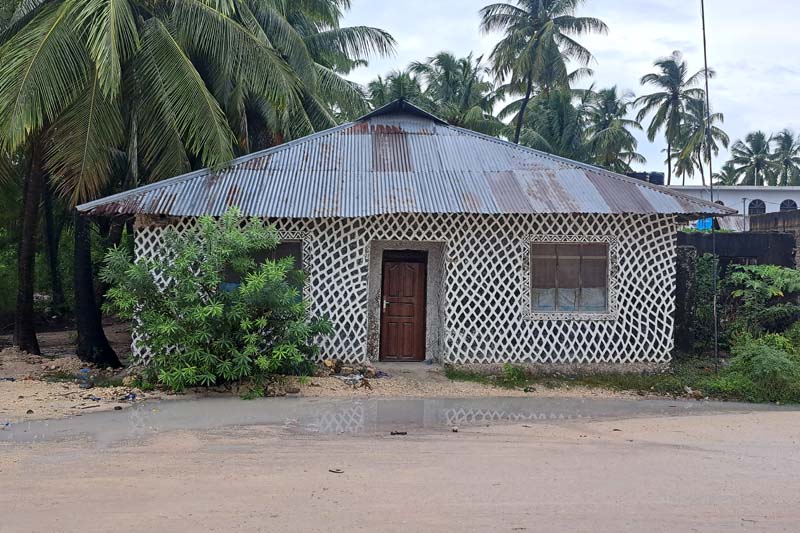

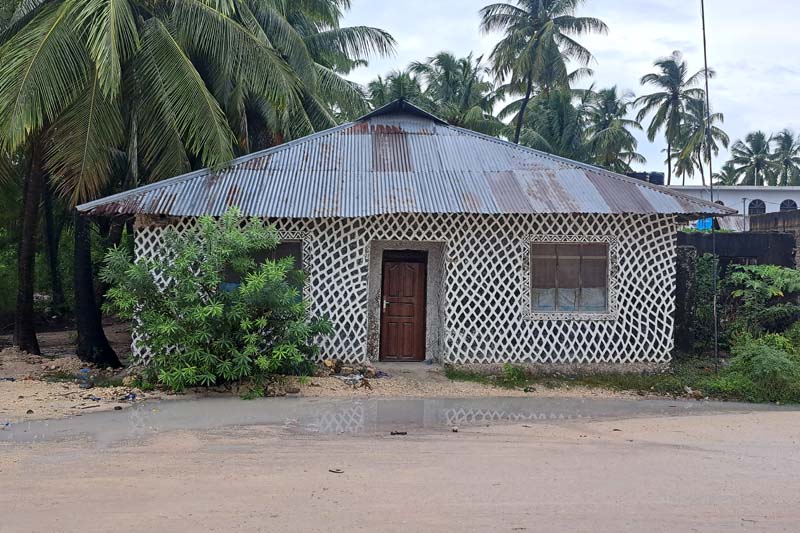

A decorated house in Jambiani.

[1] Westcott, N. (2020) Imperialism and Development: The East African Groundnut Scheme and its legacy, James Currey, p. XII.

[2] Esselborne, S. (2013) ‘Environment, Memory and the Groundnut Scheme’, Global Environment, 11, 58-93.

[3] Scott, J.C. (1998) Seeing like a State, Yale University Pres.

[4] Callaci, E. (2015) ‘Chief village in a nation of villages’: history, race and authority in Tanzania’s Dodoma plan, Urban History, 43.

[5] Project Planning Associates Limited, National Capital Master Plan, Dodoma, Tanzania (The Associates, 1976). Quoted in Callaci (2015)

[6] Van Ginneken, The burden of being planned. How African cities can learn from experiments of the past: New Town Dodoma, Tanzania. https://www.newtowninstitute.org/spip.php?article1050

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Jul 29, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this second installment of his travel blog, he recounts his encounters across Tanzania. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo."

------

Kaitu, who accompanied us for part of this trip, is very talkative and boundlessly generous. He now lives and teaches at the University in Dar es Salaam, but like most of the people I spoke with in this city, his origins are elsewhere. He was born in Bukoba, in the Northwest of Tanzania, along the shores of the Lake Victoria. After many years living abroad in Belgium, he is now back in his home country and is quickly readapting to a lifestyle, culture, and city to which he always knew he would eventually return. During the few weeks of my stay in Tanzania, he largely made up for my lack of experience of the country.

We’ve been driving for less than an hour on Bagamoyo Road, and he has already reviewed 50 years of post-independence Tanzanian political history for us. The avenue runs in north-south direction, parallel to the coast, and links Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, to Bagamoyo, the old capital of German East Africa and formerly an important trading centre. On the east side of the road, rows of hotels facing the ocean are punctuated by shopping malls covered in advertising signs written in Chinese. Lucia joins me for this part of the trip. She had never been to Africa before and is excited by the tropical setting and the customizations of buses and bajajis, the painted shop signs, and only slightly intimidated by the overcrowded Kariakoo market.

Painted shop signs in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma

The covered market in the Kariakoo district, Dar es Salaam. Opened in 1974 and designed by Beda Amuli, who established the first African architectural firm across East and Central Africa.

Tanzania gained independence from British rule in 1961, and the stories that guide the trajectory of this trip have their roots in colonial history and much of their development in independent Tanzania. These stories show, once again, that political milestones like independence are not clear-cut boundaries but are hinges of change, whose trajectory is largely defined by the conditions and visions of the future inherited by the generation responsible for such transition.

There are many ways to approach and tell this story. The one I have chosen is certainly partial. It draws from another chapter—adding to the one recounted in my previous travel report—of the broad history of how the natural resources of the African continent and the opportunities they offered for large-scale agricultural development have been the subject of ambitious projects for transforming the countryside. In Tanzania, these projects have served as a testing ground for the creation of an independent state and a new national identity. This process has made the countryside central to discussions where Western views differ significantly from local opinions. Although this journey cannot settle these differences, it provides an opportunity for them to emerge through encounters with the places and people who have experienced such change firsthand.

Mwalimu

Kaitu’s opinions on the recent political history of his country are generally cautious. He carefully weighs the pros and cons. Yet, on two things he seems to have no doubt. The first is that Julius Nyerere, the last Prime Minister of British Tanganyika and the first (and much revered) president of independent Tanzania— also known as ‘Mwalimu’ (‘teacher’ in Swahili) — has been the most important political figure in the country's history. The second is that Ujamaa, Nyerere’s political philosophy of choice marketed as the African original way to socialism, is responsible for making the country what it is despite the mistakes made in its implementation.

Nyerere square in Dodoma

Painting by John Masanja and Festo Kijo: Mwalimu Nyerere teaches a class

He takes us to visit the University of Dar es Salaam campus, where he teaches. The campus is large, with buildings spread across a hilly green landscape. It is named after 'Mwalimu' Nyerere, whose role in postcolonial African history is highlighted especially by placing him alongside other key figures of the Pan-Africanist movement. Among them is Kwame Nkrumah, perhaps the most representative figure of this movement, after whom the main conference hall on the campus is dedicated. Like Nyerere, Nkrumah was the last Prime Minister of his country, modern-day Ghana, under colonial rule and the first President after independence.

In the National Museum, a large part of the paintings and photos in the gallery are dedicated to Nyerere. These range from conventional portraits to less common depictions of him as a teacher, in military attire during the Uganda-Tanzania war of the late 1970s, or meeting with local and foreign authorities. In Dodoma, the political capital of Tanzania, what seems to be the only true square, at least in the traditionally European sense of the term, is dedicated to him. His statue, raising the ceremonial baton, stands on a white marble pedestal at the center of the open space, surrounded by greenery.

In Tanzania, cities, campuses, and museums celebrate the father of the nation with monuments, paintings, public buildings, and squares. But for Nyerere, and to a large extent for the international bodies that supported his postcolonial policies, the future of Tanzania was largely to be found in transforming the countryside.

The Nkrumah Hall in the campus of the ‘Mwalimu Nyerere’ Dar es Salaam University.

Detail of the drain and the collection basin. In the background, the chemistry department.

Half London

‘Half London’ or ‘Londoni’, in Kongwa, a town along the Dar es Salaam-Dodoma bus route, might be a strange place to begin telling the recent history of Tanzania’s development and of the belief that the answers to its future would come from its peasant communities. Writing about a visit he made there in 1982, Nicholas Westcott, Professor of Practice in the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS University of London, recalls the neighbourhood as a ghost town:

“Empty concrete platforms lay among the thorn bush, steps leading up to emptiness, where a long-vanished veranda used to stand. A waterless washbasin stood alone on one. A small overgrown roundabout in the middle of nowhere had one or two barely legible road signs: ‘Piccadilly’, ‘The Strand’ … and a small stretch of tarmac ran 30 yards from each of the turnings until it petered out into sandy track.” [1]

More than forty years after Westcott visit, even less remains. The only visible traces that seem to have survived the passage of time and the inattention of the inhabitants of Kongwa, are the remnants of the old Overseas Food Corporation headquarters, now part of a school complex.

Still from the colour film 'The Groundnut Scheme at Kongwa Tanganyika', 1948. TR 17RAN PH6/49. University of Reading. https://vrr.reading.ac.uk/records/TR_17RAN_PH6/49

Book cover of ‘The groundnut affair’ by Alan Wood, one of the many publications recounting the story of a scheme that became a widely known symbol of the failure of late colonial aspirations.

That ‘the Overseas’, as it is remembered in Westcott's brief notes, and its most direct predecessor, the Groundnut Scheme, have not left an indelible mark on the collective memory of Tanzanians is confirmed by the fact that none of the people I spoke to during these weeks of travel had ever heard of it. Yet, among specialists in recent African history, the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme, inaugurated in 1946 and abandoned five years later, is without doubt one of the most famous development programs of the late British colonial period.

The scheme was a joint venture between the United African Company, a subsidiary of Unilever, and the colonial state and was one of the largest of this kind in history. It aimed to cultivate vast areas of land in modern-day Tanzania to produce groundnuts (peanuts), which were intended to help alleviate post-war food shortages and provide raw materials for the British food and oil industries. The scheme is famous among development experts and historians mainly for two reasons: Its enormous financial and geographical scale—occupying 1.2 million-hectares and costing the equivalent of £1 billion today, five times the total annual budget of the Tanganyika Administration—and the equally proportionate scale of its fiasco.

It is precisely its reputation as a cautionary tale of how large-scale development projects can fail due to poor planning, lack of understanding of local conditions, and logistical challenges that drives me to follow its traces. Failures, especially when they mark an era of development policies, like the Groundnut Scheme, may leave fewer obvious traces, but that does not make them any less significant. Its legacy in the political and environmental history of Tanzania goes beyond the often-tenuous connection to the physical sites of the project [2] and a curious place name lost in the arid highlands of Kongwa. As James Scott called it, the groundnut scheme was a ‘dress rehearsal’ for the even larger Tanzanian 'villagization' campaign in the 1970s. [3]

Ujamaa village stamp commemorating Tanzania 10th anniversary of Independence.

Ujamaa

Mabwe Pande and Kerege settlements lie both in a slightly hilly area not far from the coast. Neither settlement appears to have a central node. They spread out with low density over a relatively large area considering the limited number of inhabitants, with single-family home lots interspersed with small plots for cultivation and the larger compounds hosting schools, hospitals, and churches. The main difference between the two is that Kerege is traversed by a busy national road crowded with heavily loaded trucks and the ubiquitous dala dala—minibuses that are the primary public transportation system in the country. Mabwe Pande, instead, is located a few kilometers away from the same road and is reached by a dirt road ending at the protected natural area of Pande Game Reserve. According to Mabwe Pande’s inhabitants, the village is becoming increasingly popular destination for residents of Dar es Salaam seeking refuge from the city's congestion.

Even a trained eye would struggle to recognize any specific features or deduce the origins of these two settlements without a local guide. In Kerege, before being accompanied by one of its original inhabitants, who moved there with his family at the time of its founding in the 1960s, we go through the extremely cordial, and equally verbose, procedures of party bureaucracy. The same party founded by Nyerere, one of the longest-ruling parties in Africa.

Kerege and Mabwe Pande are two of the thousands of villages (estimates of the total number vary depending on classifications and the various phases of implementation) founded in Tanzania between the 1960s and the mid-1980s. They were created as part of a villagization policy aimed at transforming rural society by resettling scattered rural populations into planned villages known as Ujamaa villages. This policy was a cornerstone of Nyerere's broader Ujamaa socialist ideology, intending to foster collective agriculture, communal living, and social cohesion among rural communities.

“The growth of village life will help us in improving our system of democratic government,” Nyerere declared in his inaugural presidential speech in 1962. “I intend first to set up a new department: the Department of Development Planning. This Department will be directly under my control, and it will make every effort to prepare plans for village development for the whole country as quickly as possible.”

The school in Mabwe Pande.

A water tank in the school courtyard.

The old dispensary, now adjacent to a new building, is currently used as a warehouse.

Visiting the two villages confirms what archives and publications initially suggested. Kerege was one of the pilot projects used to test and showcase the Ujamaa village concept to foreign authorities as evidence of the success of rural socialization in the country. Residents recall frequent visits in the 1970s by Chinese, Russian, and Western officials due to its proximity to Dar es Salaam and its location along a major transport route. This explains both the vividness with which its history is recounted by its inhabitants and the material traces that remain. The village focused on cashew nut production, and some of the houses built for its residents within a 2.5-kilometer radius of the village center are still extant, along with rows of houses for the ‘experts’ and some infrastructure built with contributions from village members.

In contrast, Mabwe Pande’s lack of a representative role makes public intervention less noticeable, which seems to affect how its history is remembered by its residents. Or perhaps the absence of party representatives makes people more willing to share its history in less one-sidedly positive terms. As one resident recounts, when village construction began in 1964, those already living within the designated area were allowed to stay. However, other cooperative members were brought in from nearby lands and were forced to leave their owned and cultivated land to move to the new center.

“They were given half an acre of land to build their own house and for a vegetable garden." The cotton farm where everyone worked, instead, remained outside the village”.

Kerege: one of the “experts’ houses” with the green flag of the Party of the Revolution.

A now-closed shop window surreptitiously opened into a wall. The only shop in Kerege while the Ujamaa program was active had been converted from one of the communal storage warehouses in the center of the village.

Chief village in a nation of villages

We missed the inauguration of the first electric passenger train connecting Dar es Salaam with Tanzania's political capital, Dodoma, by just a few days. The railway line has existed since the days of German East Africa, but we are told, it has been virtually unused for a long time. Indeed, the traffic between the two cities is far from intense. Dodoma is not a tourist destination, and it has only recently begun to play a significant role as an administrative center following the transfer of some ministries. Despite being designated as the capital over 50 years ago, when Nyerere announced plans to shift the national capital from the coastal Dar es Salaam to a new city in the center of the country, Dodoma's development has been slow.

It is all too obvious to describe Dodoma as a quiet city. The landscape is a flat, semi-arid plateau covered with sparse vegetation, mostly acacia shrubs, and punctuated by scattered hills that rise abruptly from the flat terrain as if placed there by chance. Atop one of these hills, sits the residence of the head of state, which visually dominates the city. The city spreads horizontally, and even recent developments like the new university campus and the new decentralized railway station contribute to fragmented urban growth. Although the history of Dodoma's master plan is troubled and none of the many proposals have ever been fully completed, this weak urbanity, which contrasts to the cosmopolitan image of Dar es Salaam, is not surprising given the vision of the country's intellectual and political leaders in the post-independence era. As contradictory as it may sound, villagization inspired the single most relevant urban project that Tanzania underwent since independence.

Amidst a global movement for pan-African renaissance, as Emily Callaci brilliantly observed [4], Tanzanian nationalism reframed coastal urbanism as a symbol of foreign domination. The Dodoma plan promised a decolonized, genuinely African modern city envisioned not as another stratified and diverse city marked by a violent world history, but rather as a rural city, created and inhabited by peasants. While Ujamaa villagization aimed to establish new villages throughout the country, Dodoma was conceived, in Nyerere's words, as 'the chief village in a nation of villages’. [5]

The Dodoma Masterplan: the new capital city is conceived as a juxtaposition of villages.

Wandering through parts of Dodoma I believe, based on my attempts to match the 1976 master plan with satellite views, to have been built according to the original idea, I searched for the physical expression of the African authenticity advocated by the scheme’s proponents. The result is unexpected: Small clusters of houses arranged around large communal open spaces, winding roads, and houses set generously amid the vegetation.

Dodoma is one of the very few cities I have visited where you can literally walk from the city center to the airport. Beyond the airport strip lies a neighborhood whose layout resembles the one envisioned in the original master plan. As we walked through it, we came across two unusually large open spaces that serve as the public core of the neighborhood. Groups of boys are playing football, a few cows are grazing, and the silhouette of the hill where the new state house was built stands out in the background. Around these spaces, rows of houses arranged in various blocks are visible. I recognize some of the prototype houses designed by the Canadian firm ‘Project Planning Associates Limited’ (PPAL), which exhibit distinctly Western, if not North American, 1970s architecture. Between these blocks, the semi-public spaces are carefully designed to minimize the impact of cars. The more you explore this part of the city, the more it resembles a wealthy “suburbia.”

Residences designed by PPAL

The winding flowerbeds that border the parking spaces within the blocks.

Some of the houses are numbered with the initial CDA most probably meaning Capital Development Authority.

As Sophie van Ginneken notes [6], Dodoma is a weird assemblage. Given the socialist aims of the new capital city and Nyerere’s reliance on local rural tradition, it is fairly ironic that a Canadian office was asked to design the Dodoma master plan. But because of the choice made by Tanzanian authorities, it is not surprising that the final design borrowed from the American suburban planning model. The outcome of such combination reflects a blend of contrasting ideologies, compromises, and the practical challenges of implementation. The concrete realization of the 'weak urbanity' envisioned in the original plan—meant to exemplify an alternative, truly African approach to urban planning for a peasant class—is instead embodied by clusters of villas in neighborhood units, where Dodoma’s middle and upper classes live.

In this regard, Dodoma’s planning experience helps us piece together the fragments of this journey. If I started by telling this story from one of the most spectacular fiascos of late colonial history, Ujamaa villagization policy, not unlike the groundnut scheme, failed catastrophically. My perspective inevitably centers on the forced resettlement and the coercive practices used by the regime to support villagization, and the work of many has documented these testimonies [7]. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the policy faced significant challenges, including economic inefficiencies, resistance from rural communities, and administrative problems. The forced relocations disrupted traditional farming practices, and many villages struggled with inadequate resources and infrastructure. By the mid-1980s, the policy was gradually phased out in favour of strategies that better addressed economic realities and development needs.

Ironically, today, in its common usage, the word Ujamaa has lost much of its explicit connection to an ideological and governmental program. In Zanzibar and in Dar es Salaam, luxury resorts use the name to evoke a sense of cosiness, cordiality, and familiar comfort. The expression is mostly understood as a generic appeal to equality and solidarity. Just as the silhouette of famous Mount Kilimanjaro is a catchy Tanzanian symbol for tourists, so is Ujamaa. Yet, once again, I try not to remain blind to the wider impact these experiences have had on the way Tanzanians perceive themselves and their national identity. If one should remain sceptical to the often reductionist views of Africa as merely a ‘testing ground’ or ‘laboratory,’ Tanzanian history in the second half of the 20th century reminds us that failures, contradictions, and compromises are inherent in periods of transition. Even when they leave less evident traces, their legacy is significant to capture the full scope of national development and identity formation.

Mount Kilimajaro, a recognizable symbol of Tanzania, in a diner in Dodoma.

A decorated house in Jambiani.

[1] Westcott, N. (2020) Imperialism and Development: The East African Groundnut Scheme and its legacy, James Currey, p. XII.

[2] Esselborne, S. (2013) ‘Environment, Memory and the Groundnut Scheme’, Global Environment, 11, 58-93.

[3] Scott, J.C. (1998) Seeing like a State, Yale University Pres.

[4] Callaci, E. (2015) ‘Chief village in a nation of villages’: history, race and authority in Tanzania’s Dodoma plan, Urban History, 43.

[5] Project Planning Associates Limited, National Capital Master Plan, Dodoma, Tanzania (The Associates, 1976). Quoted in Callaci (2015)

[6] Van Ginneken, The burden of being planned. How African cities can learn from experiments of the past: New Town Dodoma, Tanzania. https://www.newtowninstitute.org/spip.php?article1050

2024 Recipients

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Jul 29, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this second installment of his travel blog, he recounts his encounters across Tanzania. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo."

------

Kaitu, who accompanied us for part of this trip, is very talkative and boundlessly generous. He now lives and teaches at the University in Dar es Salaam, but like most of the people I spoke with in this city, his origins are elsewhere. He was born in Bukoba, in the Northwest of Tanzania, along the shores of the Lake Victoria. After many years living abroad in Belgium, he is now back in his home country and is quickly readapting to a lifestyle, culture, and city to which he always knew he would eventually return. During the few weeks of my stay in Tanzania, he largely made up for my lack of experience of the country.

We’ve been driving for less than an hour on Bagamoyo Road, and he has already reviewed 50 years of post-independence Tanzanian political history for us. The avenue runs in north-south direction, parallel to the coast, and links Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, to Bagamoyo, the old capital of German East Africa and formerly an important trading centre. On the east side of the road, rows of hotels facing the ocean are punctuated by shopping malls covered in advertising signs written in Chinese. Lucia joins me for this part of the trip. She had never been to Africa before and is excited by the tropical setting and the customizations of buses and bajajis, the painted shop signs, and only slightly intimidated by the overcrowded Kariakoo market.

Painted shop signs in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma

The covered market in the Kariakoo district, Dar es Salaam. Opened in 1974 and designed by Beda Amuli, who established the first African architectural firm across East and Central Africa.

Tanzania gained independence from British rule in 1961, and the stories that guide the trajectory of this trip have their roots in colonial history and much of their development in independent Tanzania. These stories show, once again, that political milestones like independence are not clear-cut boundaries but are hinges of change, whose trajectory is largely defined by the conditions and visions of the future inherited by the generation responsible for such transition.

There are many ways to approach and tell this story. The one I have chosen is certainly partial. It draws from another chapter—adding to the one recounted in my previous travel report—of the broad history of how the natural resources of the African continent and the opportunities they offered for large-scale agricultural development have been the subject of ambitious projects for transforming the countryside. In Tanzania, these projects have served as a testing ground for the creation of an independent state and a new national identity. This process has made the countryside central to discussions where Western views differ significantly from local opinions. Although this journey cannot settle these differences, it provides an opportunity for them to emerge through encounters with the places and people who have experienced such change firsthand.

Mwalimu

Kaitu’s opinions on the recent political history of his country are generally cautious. He carefully weighs the pros and cons. Yet, on two things he seems to have no doubt. The first is that Julius Nyerere, the last Prime Minister of British Tanganyika and the first (and much revered) president of independent Tanzania— also known as ‘Mwalimu’ (‘teacher’ in Swahili) — has been the most important political figure in the country's history. The second is that Ujamaa, Nyerere’s political philosophy of choice marketed as the African original way to socialism, is responsible for making the country what it is despite the mistakes made in its implementation.

Nyerere square in Dodoma

Painting by John Masanja and Festo Kijo: Mwalimu Nyerere teaches a class

He takes us to visit the University of Dar es Salaam campus, where he teaches. The campus is large, with buildings spread across a hilly green landscape. It is named after 'Mwalimu' Nyerere, whose role in postcolonial African history is highlighted especially by placing him alongside other key figures of the Pan-Africanist movement. Among them is Kwame Nkrumah, perhaps the most representative figure of this movement, after whom the main conference hall on the campus is dedicated. Like Nyerere, Nkrumah was the last Prime Minister of his country, modern-day Ghana, under colonial rule and the first President after independence.

In the National Museum, a large part of the paintings and photos in the gallery are dedicated to Nyerere. These range from conventional portraits to less common depictions of him as a teacher, in military attire during the Uganda-Tanzania war of the late 1970s, or meeting with local and foreign authorities. In Dodoma, the political capital of Tanzania, what seems to be the only true square, at least in the traditionally European sense of the term, is dedicated to him. His statue, raising the ceremonial baton, stands on a white marble pedestal at the center of the open space, surrounded by greenery.

In Tanzania, cities, campuses, and museums celebrate the father of the nation with monuments, paintings, public buildings, and squares. But for Nyerere, and to a large extent for the international bodies that supported his postcolonial policies, the future of Tanzania was largely to be found in transforming the countryside.

The Nkrumah Hall in the campus of the ‘Mwalimu Nyerere’ Dar es Salaam University.

Detail of the drain and the collection basin. In the background, the chemistry department.

Half London

‘Half London’ or ‘Londoni’, in Kongwa, a town along the Dar es Salaam-Dodoma bus route, might be a strange place to begin telling the recent history of Tanzania’s development and of the belief that the answers to its future would come from its peasant communities. Writing about a visit he made there in 1982, Nicholas Westcott, Professor of Practice in the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS University of London, recalls the neighbourhood as a ghost town:

“Empty concrete platforms lay among the thorn bush, steps leading up to emptiness, where a long-vanished veranda used to stand. A waterless washbasin stood alone on one. A small overgrown roundabout in the middle of nowhere had one or two barely legible road signs: ‘Piccadilly’, ‘The Strand’ … and a small stretch of tarmac ran 30 yards from each of the turnings until it petered out into sandy track.” [1]

More than forty years after Westcott visit, even less remains. The only visible traces that seem to have survived the passage of time and the inattention of the inhabitants of Kongwa, are the remnants of the old Overseas Food Corporation headquarters, now part of a school complex.

Still from the colour film 'The Groundnut Scheme at Kongwa Tanganyika', 1948. TR 17RAN PH6/49. University of Reading. https://vrr.reading.ac.uk/records/TR_17RAN_PH6/49

Book cover of ‘The groundnut affair’ by Alan Wood, one of the many publications recounting the story of a scheme that became a widely known symbol of the failure of late colonial aspirations.

That ‘the Overseas’, as it is remembered in Westcott's brief notes, and its most direct predecessor, the Groundnut Scheme, have not left an indelible mark on the collective memory of Tanzanians is confirmed by the fact that none of the people I spoke to during these weeks of travel had ever heard of it. Yet, among specialists in recent African history, the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme, inaugurated in 1946 and abandoned five years later, is without doubt one of the most famous development programs of the late British colonial period.

The scheme was a joint venture between the United African Company, a subsidiary of Unilever, and the colonial state and was one of the largest of this kind in history. It aimed to cultivate vast areas of land in modern-day Tanzania to produce groundnuts (peanuts), which were intended to help alleviate post-war food shortages and provide raw materials for the British food and oil industries. The scheme is famous among development experts and historians mainly for two reasons: Its enormous financial and geographical scale—occupying 1.2 million-hectares and costing the equivalent of £1 billion today, five times the total annual budget of the Tanganyika Administration—and the equally proportionate scale of its fiasco.

It is precisely its reputation as a cautionary tale of how large-scale development projects can fail due to poor planning, lack of understanding of local conditions, and logistical challenges that drives me to follow its traces. Failures, especially when they mark an era of development policies, like the Groundnut Scheme, may leave fewer obvious traces, but that does not make them any less significant. Its legacy in the political and environmental history of Tanzania goes beyond the often-tenuous connection to the physical sites of the project [2] and a curious place name lost in the arid highlands of Kongwa. As James Scott called it, the groundnut scheme was a ‘dress rehearsal’ for the even larger Tanzanian 'villagization' campaign in the 1970s. [3]

Ujamaa village stamp commemorating Tanzania 10th anniversary of Independence.

Ujamaa

Mabwe Pande and Kerege settlements lie both in a slightly hilly area not far from the coast. Neither settlement appears to have a central node. They spread out with low density over a relatively large area considering the limited number of inhabitants, with single-family home lots interspersed with small plots for cultivation and the larger compounds hosting schools, hospitals, and churches. The main difference between the two is that Kerege is traversed by a busy national road crowded with heavily loaded trucks and the ubiquitous dala dala—minibuses that are the primary public transportation system in the country. Mabwe Pande, instead, is located a few kilometers away from the same road and is reached by a dirt road ending at the protected natural area of Pande Game Reserve. According to Mabwe Pande’s inhabitants, the village is becoming increasingly popular destination for residents of Dar es Salaam seeking refuge from the city's congestion.

Even a trained eye would struggle to recognize any specific features or deduce the origins of these two settlements without a local guide. In Kerege, before being accompanied by one of its original inhabitants, who moved there with his family at the time of its founding in the 1960s, we go through the extremely cordial, and equally verbose, procedures of party bureaucracy. The same party founded by Nyerere, one of the longest-ruling parties in Africa.

Kerege and Mabwe Pande are two of the thousands of villages (estimates of the total number vary depending on classifications and the various phases of implementation) founded in Tanzania between the 1960s and the mid-1980s. They were created as part of a villagization policy aimed at transforming rural society by resettling scattered rural populations into planned villages known as Ujamaa villages. This policy was a cornerstone of Nyerere's broader Ujamaa socialist ideology, intending to foster collective agriculture, communal living, and social cohesion among rural communities.

“The growth of village life will help us in improving our system of democratic government,” Nyerere declared in his inaugural presidential speech in 1962. “I intend first to set up a new department: the Department of Development Planning. This Department will be directly under my control, and it will make every effort to prepare plans for village development for the whole country as quickly as possible.”

The school in Mabwe Pande.

A water tank in the school courtyard.

The old dispensary, now adjacent to a new building, is currently used as a warehouse.

Visiting the two villages confirms what archives and publications initially suggested. Kerege was one of the pilot projects used to test and showcase the Ujamaa village concept to foreign authorities as evidence of the success of rural socialization in the country. Residents recall frequent visits in the 1970s by Chinese, Russian, and Western officials due to its proximity to Dar es Salaam and its location along a major transport route. This explains both the vividness with which its history is recounted by its inhabitants and the material traces that remain. The village focused on cashew nut production, and some of the houses built for its residents within a 2.5-kilometer radius of the village center are still extant, along with rows of houses for the ‘experts’ and some infrastructure built with contributions from village members.

In contrast, Mabwe Pande’s lack of a representative role makes public intervention less noticeable, which seems to affect how its history is remembered by its residents. Or perhaps the absence of party representatives makes people more willing to share its history in less one-sidedly positive terms. As one resident recounts, when village construction began in 1964, those already living within the designated area were allowed to stay. However, other cooperative members were brought in from nearby lands and were forced to leave their owned and cultivated land to move to the new center.

“They were given half an acre of land to build their own house and for a vegetable garden." The cotton farm where everyone worked, instead, remained outside the village”.

Kerege: one of the “experts’ houses” with the green flag of the Party of the Revolution.

A now-closed shop window surreptitiously opened into a wall. The only shop in Kerege while the Ujamaa program was active had been converted from one of the communal storage warehouses in the center of the village.

Chief village in a nation of villages

We missed the inauguration of the first electric passenger train connecting Dar es Salaam with Tanzania's political capital, Dodoma, by just a few days. The railway line has existed since the days of German East Africa, but we are told, it has been virtually unused for a long time. Indeed, the traffic between the two cities is far from intense. Dodoma is not a tourist destination, and it has only recently begun to play a significant role as an administrative center following the transfer of some ministries. Despite being designated as the capital over 50 years ago, when Nyerere announced plans to shift the national capital from the coastal Dar es Salaam to a new city in the center of the country, Dodoma's development has been slow.

It is all too obvious to describe Dodoma as a quiet city. The landscape is a flat, semi-arid plateau covered with sparse vegetation, mostly acacia shrubs, and punctuated by scattered hills that rise abruptly from the flat terrain as if placed there by chance. Atop one of these hills, sits the residence of the head of state, which visually dominates the city. The city spreads horizontally, and even recent developments like the new university campus and the new decentralized railway station contribute to fragmented urban growth. Although the history of Dodoma's master plan is troubled and none of the many proposals have ever been fully completed, this weak urbanity, which contrasts to the cosmopolitan image of Dar es Salaam, is not surprising given the vision of the country's intellectual and political leaders in the post-independence era. As contradictory as it may sound, villagization inspired the single most relevant urban project that Tanzania underwent since independence.

Amidst a global movement for pan-African renaissance, as Emily Callaci brilliantly observed [4], Tanzanian nationalism reframed coastal urbanism as a symbol of foreign domination. The Dodoma plan promised a decolonized, genuinely African modern city envisioned not as another stratified and diverse city marked by a violent world history, but rather as a rural city, created and inhabited by peasants. While Ujamaa villagization aimed to establish new villages throughout the country, Dodoma was conceived, in Nyerere's words, as 'the chief village in a nation of villages’. [5]

The Dodoma Masterplan: the new capital city is conceived as a juxtaposition of villages.

Wandering through parts of Dodoma I believe, based on my attempts to match the 1976 master plan with satellite views, to have been built according to the original idea, I searched for the physical expression of the African authenticity advocated by the scheme’s proponents. The result is unexpected: Small clusters of houses arranged around large communal open spaces, winding roads, and houses set generously amid the vegetation.

Dodoma is one of the very few cities I have visited where you can literally walk from the city center to the airport. Beyond the airport strip lies a neighborhood whose layout resembles the one envisioned in the original master plan. As we walked through it, we came across two unusually large open spaces that serve as the public core of the neighborhood. Groups of boys are playing football, a few cows are grazing, and the silhouette of the hill where the new state house was built stands out in the background. Around these spaces, rows of houses arranged in various blocks are visible. I recognize some of the prototype houses designed by the Canadian firm ‘Project Planning Associates Limited’ (PPAL), which exhibit distinctly Western, if not North American, 1970s architecture. Between these blocks, the semi-public spaces are carefully designed to minimize the impact of cars. The more you explore this part of the city, the more it resembles a wealthy “suburbia.”

Residences designed by PPAL

The winding flowerbeds that border the parking spaces within the blocks.

Some of the houses are numbered with the initial CDA most probably meaning Capital Development Authority.

As Sophie van Ginneken notes [6], Dodoma is a weird assemblage. Given the socialist aims of the new capital city and Nyerere’s reliance on local rural tradition, it is fairly ironic that a Canadian office was asked to design the Dodoma master plan. But because of the choice made by Tanzanian authorities, it is not surprising that the final design borrowed from the American suburban planning model. The outcome of such combination reflects a blend of contrasting ideologies, compromises, and the practical challenges of implementation. The concrete realization of the 'weak urbanity' envisioned in the original plan—meant to exemplify an alternative, truly African approach to urban planning for a peasant class—is instead embodied by clusters of villas in neighborhood units, where Dodoma’s middle and upper classes live.

In this regard, Dodoma’s planning experience helps us piece together the fragments of this journey. If I started by telling this story from one of the most spectacular fiascos of late colonial history, Ujamaa villagization policy, not unlike the groundnut scheme, failed catastrophically. My perspective inevitably centers on the forced resettlement and the coercive practices used by the regime to support villagization, and the work of many has documented these testimonies [7]. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the policy faced significant challenges, including economic inefficiencies, resistance from rural communities, and administrative problems. The forced relocations disrupted traditional farming practices, and many villages struggled with inadequate resources and infrastructure. By the mid-1980s, the policy was gradually phased out in favour of strategies that better addressed economic realities and development needs.

Ironically, today, in its common usage, the word Ujamaa has lost much of its explicit connection to an ideological and governmental program. In Zanzibar and in Dar es Salaam, luxury resorts use the name to evoke a sense of cosiness, cordiality, and familiar comfort. The expression is mostly understood as a generic appeal to equality and solidarity. Just as the silhouette of famous Mount Kilimanjaro is a catchy Tanzanian symbol for tourists, so is Ujamaa. Yet, once again, I try not to remain blind to the wider impact these experiences have had on the way Tanzanians perceive themselves and their national identity. If one should remain sceptical to the often reductionist views of Africa as merely a ‘testing ground’ or ‘laboratory,’ Tanzanian history in the second half of the 20th century reminds us that failures, contradictions, and compromises are inherent in periods of transition. Even when they leave less evident traces, their legacy is significant to capture the full scope of national development and identity formation.

Mount Kilimajaro, a recognizable symbol of Tanzania, in a diner in Dodoma.

A decorated house in Jambiani.

[1] Westcott, N. (2020) Imperialism and Development: The East African Groundnut Scheme and its legacy, James Currey, p. XII.

[2] Esselborne, S. (2013) ‘Environment, Memory and the Groundnut Scheme’, Global Environment, 11, 58-93.

[3] Scott, J.C. (1998) Seeing like a State, Yale University Pres.

[4] Callaci, E. (2015) ‘Chief village in a nation of villages’: history, race and authority in Tanzania’s Dodoma plan, Urban History, 43.

[5] Project Planning Associates Limited, National Capital Master Plan, Dodoma, Tanzania (The Associates, 1976). Quoted in Callaci (2015)

[6] Van Ginneken, The burden of being planned. How African cities can learn from experiments of the past: New Town Dodoma, Tanzania. https://www.newtowninstitute.org/spip.php?article1050

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Jul 29, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Tanzania: dreams and failures of a rural future

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this second installment of his travel blog, he recounts his encounters across Tanzania. All photographs are by the author.

Read Part One: "Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo."

------

Kaitu, who accompanied us for part of this trip, is very talkative and boundlessly generous. He now lives and teaches at the University in Dar es Salaam, but like most of the people I spoke with in this city, his origins are elsewhere. He was born in Bukoba, in the Northwest of Tanzania, along the shores of the Lake Victoria. After many years living abroad in Belgium, he is now back in his home country and is quickly readapting to a lifestyle, culture, and city to which he always knew he would eventually return. During the few weeks of my stay in Tanzania, he largely made up for my lack of experience of the country.

We’ve been driving for less than an hour on Bagamoyo Road, and he has already reviewed 50 years of post-independence Tanzanian political history for us. The avenue runs in north-south direction, parallel to the coast, and links Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, to Bagamoyo, the old capital of German East Africa and formerly an important trading centre. On the east side of the road, rows of hotels facing the ocean are punctuated by shopping malls covered in advertising signs written in Chinese. Lucia joins me for this part of the trip. She had never been to Africa before and is excited by the tropical setting and the customizations of buses and bajajis, the painted shop signs, and only slightly intimidated by the overcrowded Kariakoo market.

Painted shop signs in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma

The covered market in the Kariakoo district, Dar es Salaam. Opened in 1974 and designed by Beda Amuli, who established the first African architectural firm across East and Central Africa.

Tanzania gained independence from British rule in 1961, and the stories that guide the trajectory of this trip have their roots in colonial history and much of their development in independent Tanzania. These stories show, once again, that political milestones like independence are not clear-cut boundaries but are hinges of change, whose trajectory is largely defined by the conditions and visions of the future inherited by the generation responsible for such transition.

There are many ways to approach and tell this story. The one I have chosen is certainly partial. It draws from another chapter—adding to the one recounted in my previous travel report—of the broad history of how the natural resources of the African continent and the opportunities they offered for large-scale agricultural development have been the subject of ambitious projects for transforming the countryside. In Tanzania, these projects have served as a testing ground for the creation of an independent state and a new national identity. This process has made the countryside central to discussions where Western views differ significantly from local opinions. Although this journey cannot settle these differences, it provides an opportunity for them to emerge through encounters with the places and people who have experienced such change firsthand.

Mwalimu

Kaitu’s opinions on the recent political history of his country are generally cautious. He carefully weighs the pros and cons. Yet, on two things he seems to have no doubt. The first is that Julius Nyerere, the last Prime Minister of British Tanganyika and the first (and much revered) president of independent Tanzania— also known as ‘Mwalimu’ (‘teacher’ in Swahili) — has been the most important political figure in the country's history. The second is that Ujamaa, Nyerere’s political philosophy of choice marketed as the African original way to socialism, is responsible for making the country what it is despite the mistakes made in its implementation.

Nyerere square in Dodoma

Painting by John Masanja and Festo Kijo: Mwalimu Nyerere teaches a class

He takes us to visit the University of Dar es Salaam campus, where he teaches. The campus is large, with buildings spread across a hilly green landscape. It is named after 'Mwalimu' Nyerere, whose role in postcolonial African history is highlighted especially by placing him alongside other key figures of the Pan-Africanist movement. Among them is Kwame Nkrumah, perhaps the most representative figure of this movement, after whom the main conference hall on the campus is dedicated. Like Nyerere, Nkrumah was the last Prime Minister of his country, modern-day Ghana, under colonial rule and the first President after independence.

In the National Museum, a large part of the paintings and photos in the gallery are dedicated to Nyerere. These range from conventional portraits to less common depictions of him as a teacher, in military attire during the Uganda-Tanzania war of the late 1970s, or meeting with local and foreign authorities. In Dodoma, the political capital of Tanzania, what seems to be the only true square, at least in the traditionally European sense of the term, is dedicated to him. His statue, raising the ceremonial baton, stands on a white marble pedestal at the center of the open space, surrounded by greenery.

In Tanzania, cities, campuses, and museums celebrate the father of the nation with monuments, paintings, public buildings, and squares. But for Nyerere, and to a large extent for the international bodies that supported his postcolonial policies, the future of Tanzania was largely to be found in transforming the countryside.

The Nkrumah Hall in the campus of the ‘Mwalimu Nyerere’ Dar es Salaam University.

Detail of the drain and the collection basin. In the background, the chemistry department.

Half London

‘Half London’ or ‘Londoni’, in Kongwa, a town along the Dar es Salaam-Dodoma bus route, might be a strange place to begin telling the recent history of Tanzania’s development and of the belief that the answers to its future would come from its peasant communities. Writing about a visit he made there in 1982, Nicholas Westcott, Professor of Practice in the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS University of London, recalls the neighbourhood as a ghost town:

“Empty concrete platforms lay among the thorn bush, steps leading up to emptiness, where a long-vanished veranda used to stand. A waterless washbasin stood alone on one. A small overgrown roundabout in the middle of nowhere had one or two barely legible road signs: ‘Piccadilly’, ‘The Strand’ … and a small stretch of tarmac ran 30 yards from each of the turnings until it petered out into sandy track.” [1]

More than forty years after Westcott visit, even less remains. The only visible traces that seem to have survived the passage of time and the inattention of the inhabitants of Kongwa, are the remnants of the old Overseas Food Corporation headquarters, now part of a school complex.

Still from the colour film 'The Groundnut Scheme at Kongwa Tanganyika', 1948. TR 17RAN PH6/49. University of Reading. https://vrr.reading.ac.uk/records/TR_17RAN_PH6/49

Book cover of ‘The groundnut affair’ by Alan Wood, one of the many publications recounting the story of a scheme that became a widely known symbol of the failure of late colonial aspirations.

That ‘the Overseas’, as it is remembered in Westcott's brief notes, and its most direct predecessor, the Groundnut Scheme, have not left an indelible mark on the collective memory of Tanzanians is confirmed by the fact that none of the people I spoke to during these weeks of travel had ever heard of it. Yet, among specialists in recent African history, the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme, inaugurated in 1946 and abandoned five years later, is without doubt one of the most famous development programs of the late British colonial period.

The scheme was a joint venture between the United African Company, a subsidiary of Unilever, and the colonial state and was one of the largest of this kind in history. It aimed to cultivate vast areas of land in modern-day Tanzania to produce groundnuts (peanuts), which were intended to help alleviate post-war food shortages and provide raw materials for the British food and oil industries. The scheme is famous among development experts and historians mainly for two reasons: Its enormous financial and geographical scale—occupying 1.2 million-hectares and costing the equivalent of £1 billion today, five times the total annual budget of the Tanganyika Administration—and the equally proportionate scale of its fiasco.