-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The prestigious H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship allows a recent graduate or emerging scholar to study by travel for one year while observing, reading, writing, or sketching. Fellowship recipients are required to document their travels through monthly posts on the SAH Blog.

2025 Amalie Elfallah

2025 Francesca Sisci

2024 Michele Tenzon

2024 Stathis G. Yeros

2023 Jasper Ludewig

2023 Annie Schentag

2022 Anne Delano Steinert

2022 Adil Mansure

2019 Sundus Al-Bayati

2018 Aymar Mariño-Maza

2018 Zachary J. Violette

2017 Sarah Rovang

2016 Adeyemi Akande

2015 Danielle S. Willkens

2014 Patricia Blessing

2013 Amber N. Wiley

2025 Recipients

Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo

Jun 17, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this first installment of his travel blog, he traces the impacts of palm oil from Europe to The Democratic Republic of the Congo.

______________________________________________________________________

This study would not have been possible without the prior knowledge acquired through archival and fieldwork research during my years as a Research Associate at the University of Liverpool, as part of the research project ‘The Architecture of United

Africa’ (Ewan Harrison, Iain Jackson, Claire Tunstall, Rixt Woudstra).

Brussels

The Western world wages a battle against palm oil, and supermarket shelves are flooded with 'palm oil-free' labels. But for much of the Global South, palm oil is everywhere. It is in every household, every market, every port, and every forest. In Europe, where this journey of mine begins and ends, aside from its highlighted absence from the favorite biscuit’s brands, traces of palm oil in everyday life and spaces are rare. The yellow jerrycans that traditionally contains this oil and that are ubiquitous in African markets, are nowhere to be found in Europe. I personally had never used it in the kitchen, although, even if we don’t necessarily notice it, it is used in many personal care and cleaning products. Before I began visiting, in the past three or four years, West and Central Africa I had never seen an oil palm, let alone a plantation, and needless to say, I had no idea about the taste that palm oil lends to Congolese pondu or Ghanaian red red.

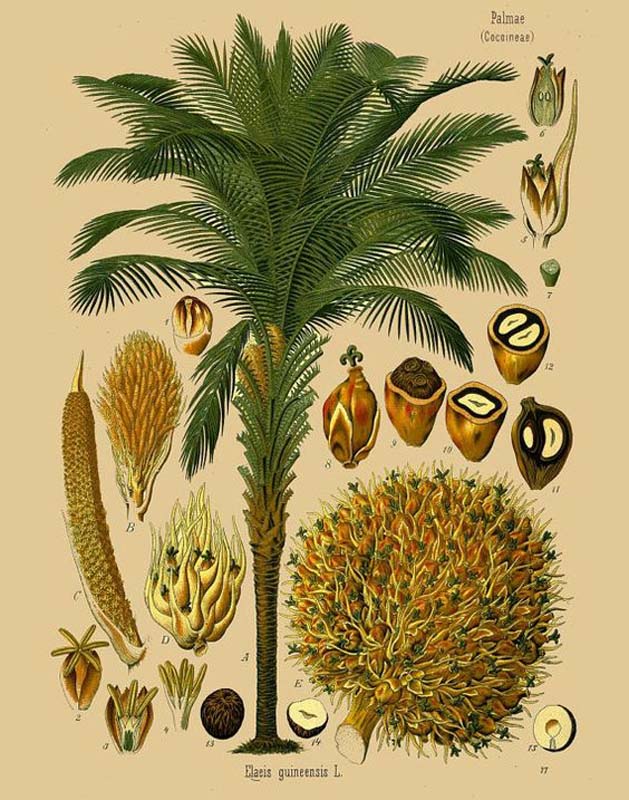

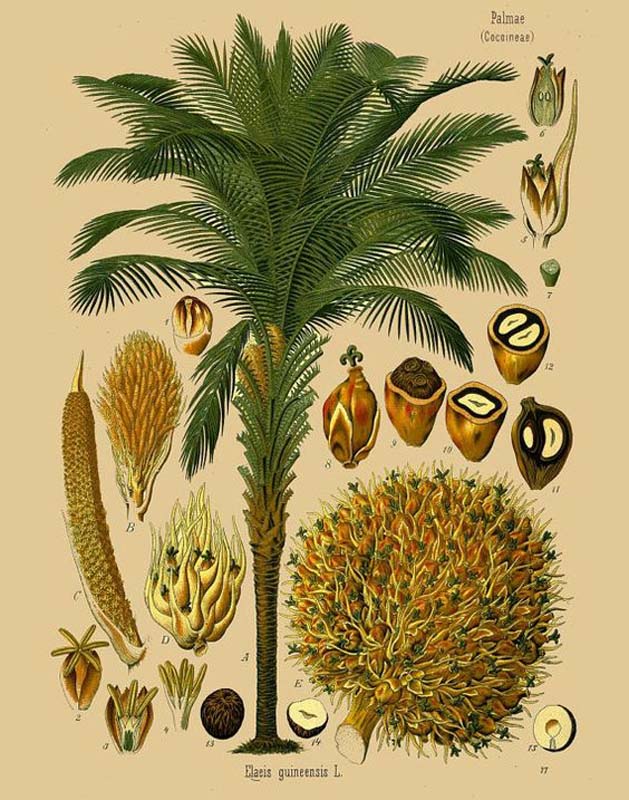

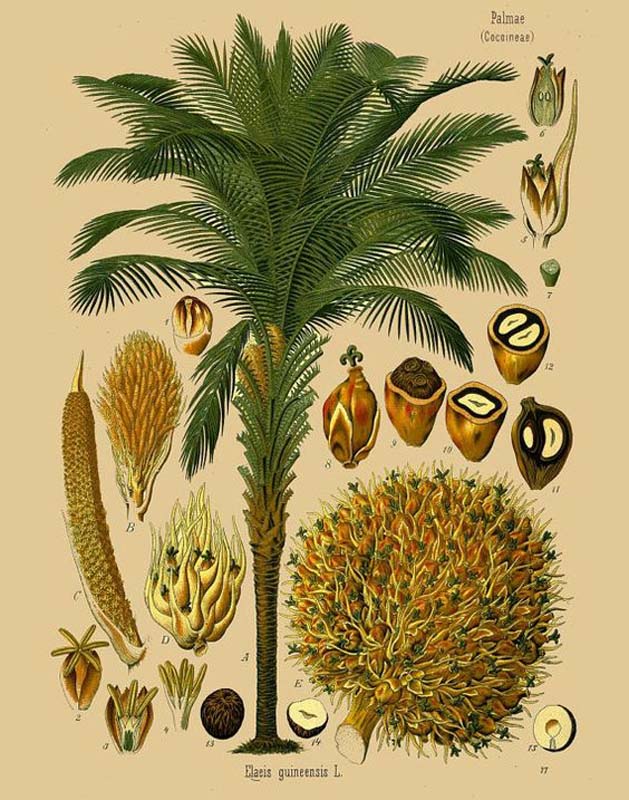

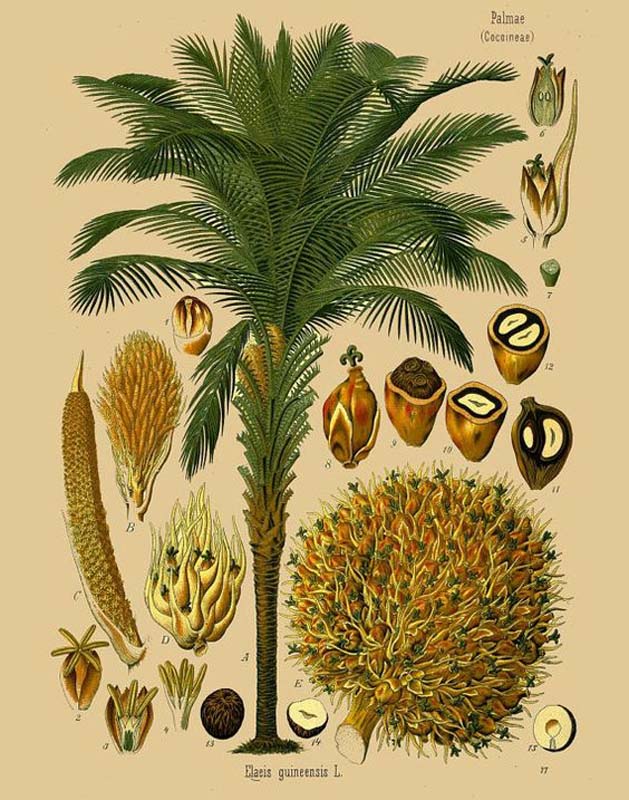

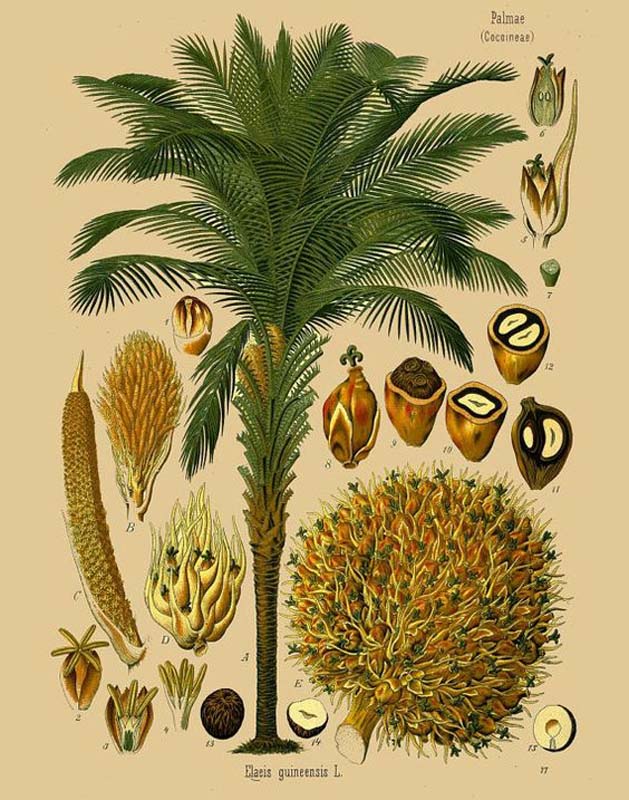

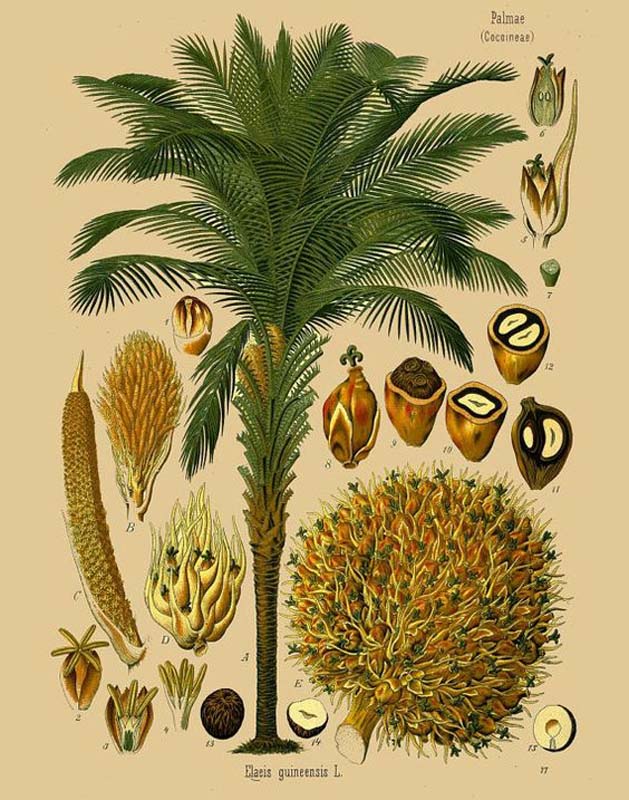

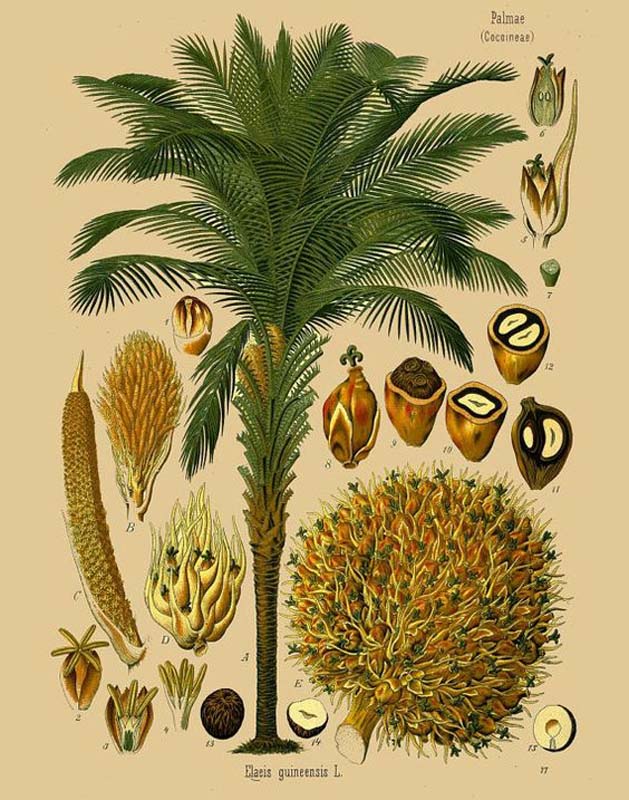

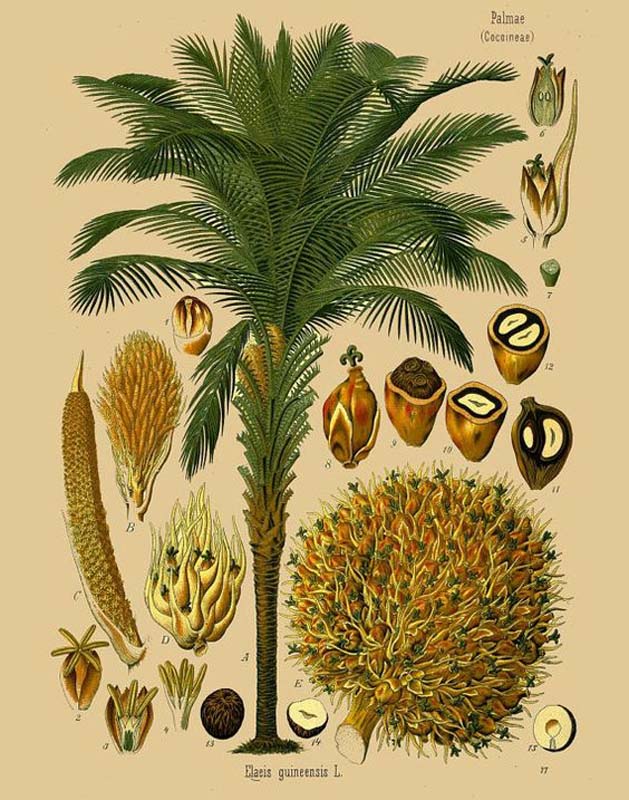

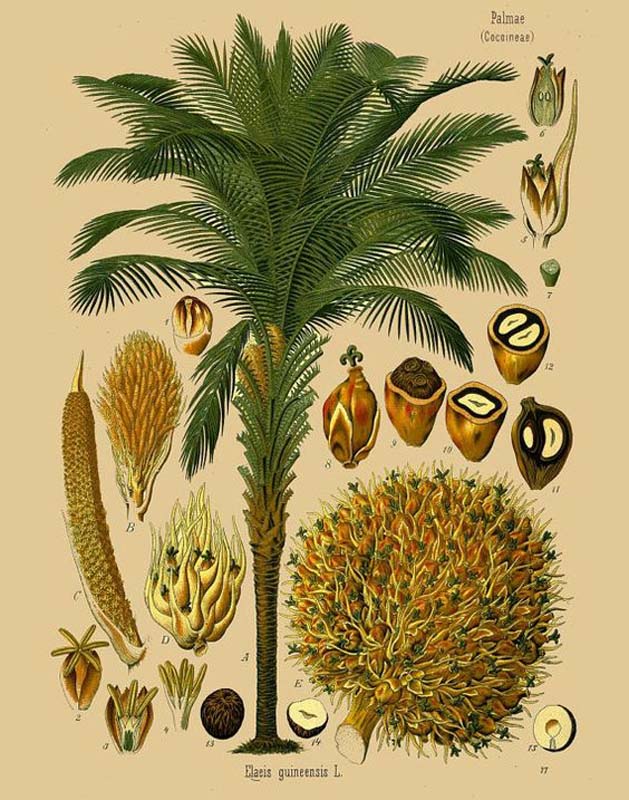

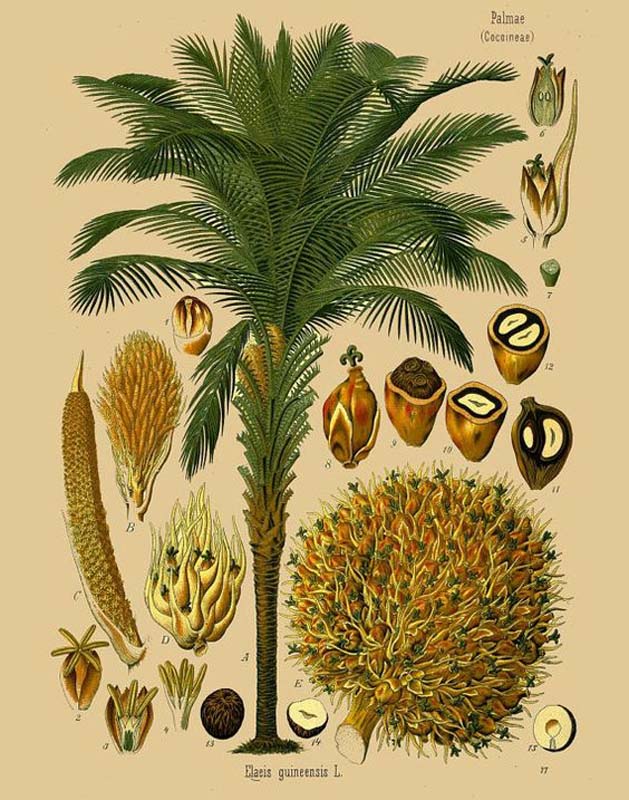

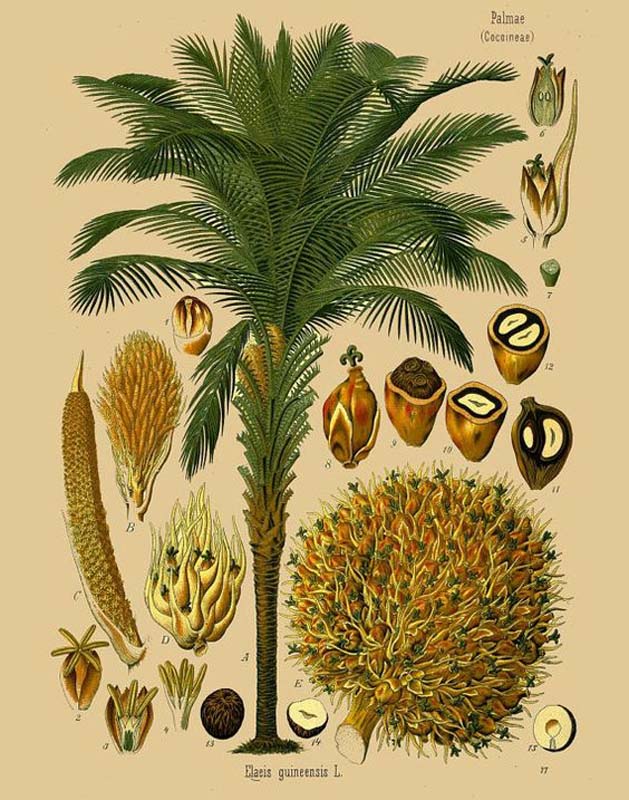

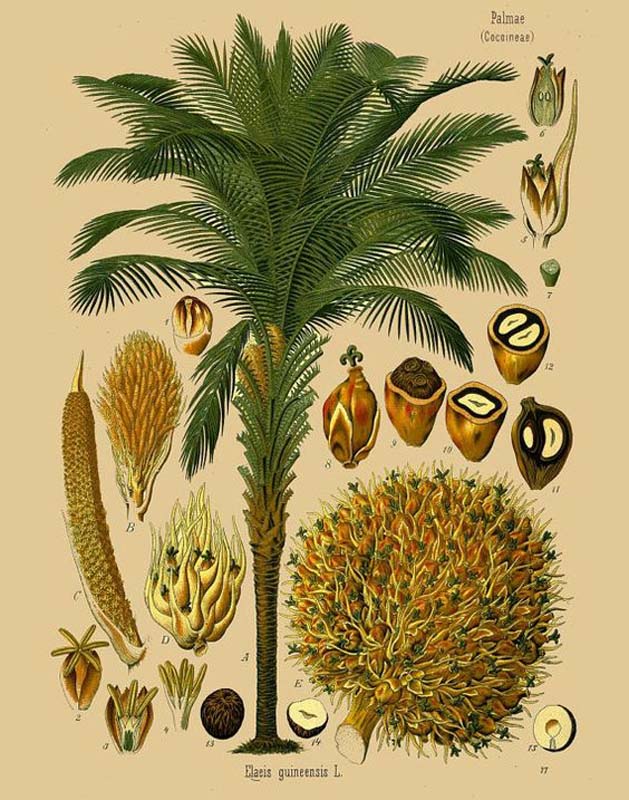

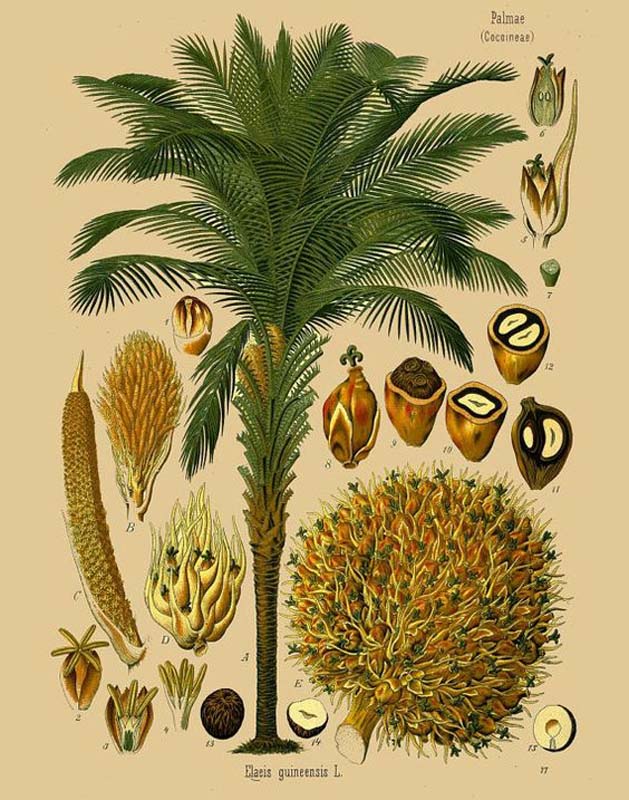

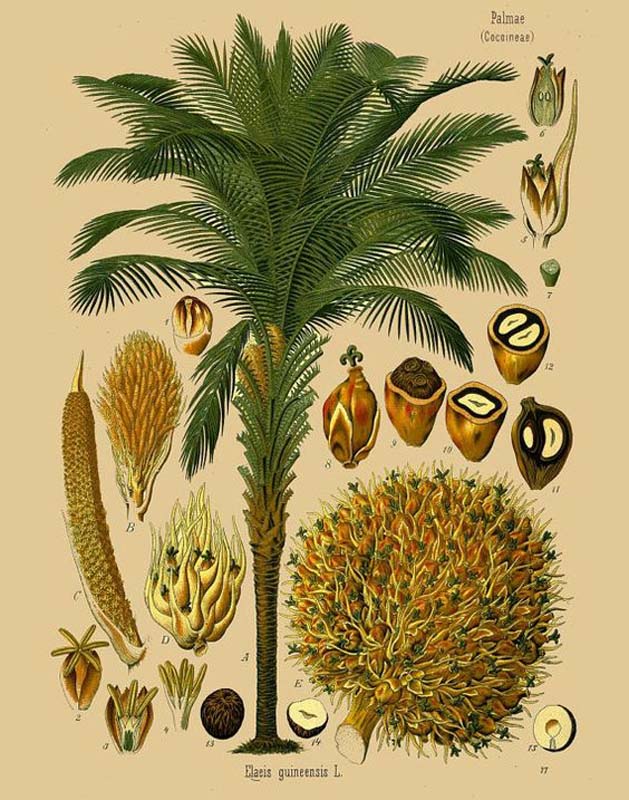

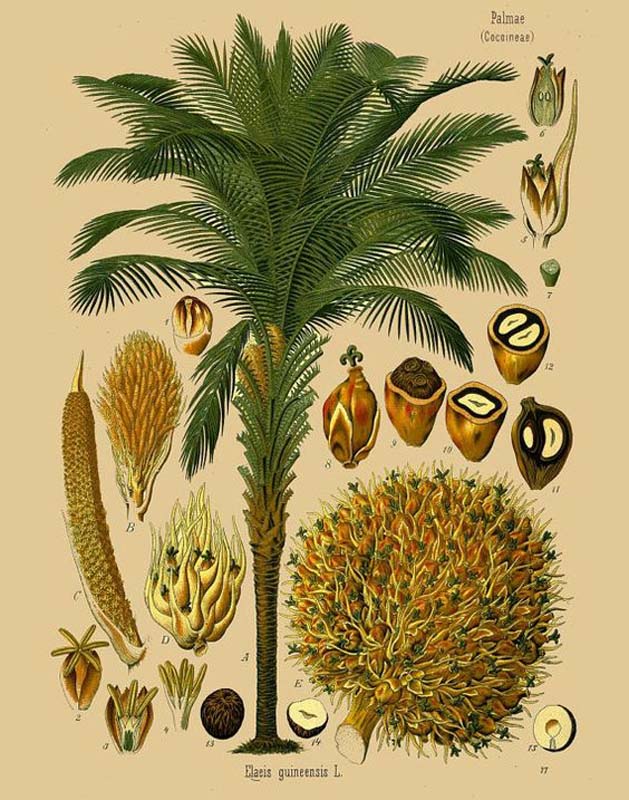

I remember stumbling upon palm oil for the first time in a natural science museum. The label affixed in front of a large bunch of reddish fruits installed in a display case stated that “from the pressing of the fruits of the oil palm, mainly spread in two species, Elaeis guineensis and Elaeis oleifera, varieties of oil are obtained for both food use and various industrial processes”. What the label didn’t say, and it would have been odd otherwise, is that, unlike in Europe, palm oil is everywhere at tropical latitudes. And that it serves as the vector for large-scale processes that have transformed entire urban and rural landscapes in the ‘oil palm belt,’ that part of the globe which includes much of West and Central Africa, Southeast Asia, and part of South America, where the climate and soil conditions are optimal for its cultivation.

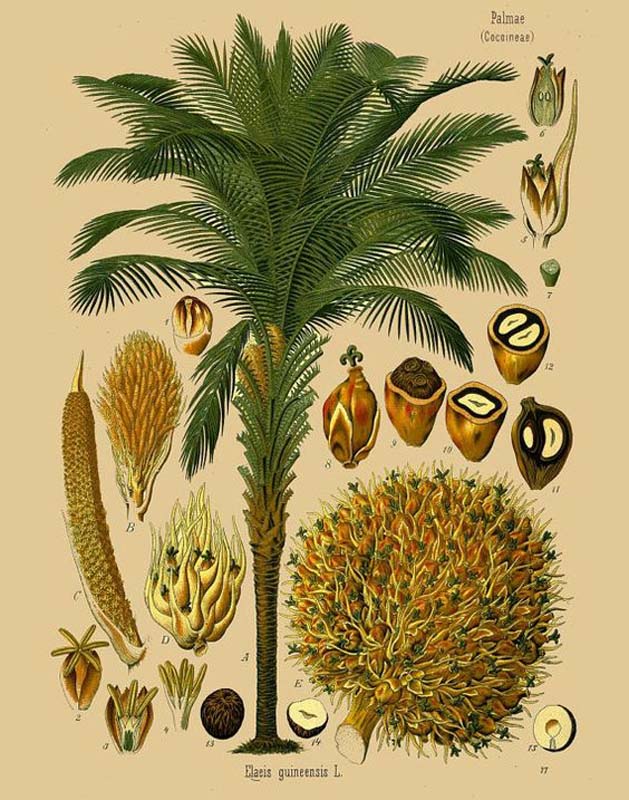

Eleais Guineensis. The tree and its fruits

The other thing that the label did not say is that these bunches of firm fruits have been, at least for the past hundred years, at the center of contradictory tales of brutal exploitation and environmental controversies, but also of hope for progress and opportunity for change. They carry the weight of a heavy historical legacy that is reflected in their collective perception, both in the Global North and South, and which is impossible to dissociate from their physical impact on the land, the natural and built environments, and the lives of those who inhabit them.

Much later, after this initial encounter, I found myself wandering in an upscale neighborhood in Brussels, in Belgium, searching for a building that I knew had once served as the headquarters of an Anglo-Belgian-Congolese company engaged in the cultivation, extraction, and processing of palm oil. I had recently begun exploring the archives of this company, the Huileries du Congo Belge, a subsidiary of the commercial empire now known as Unilever, at its British headquarters in Port Sunlight, just a few kilometers from Liverpool. This company was exporting palm oil for use in soap production, including the famous Sunlight Soap.

Stone frieze depicting palm oil production process at the entrance of the Unilever House, European Quarter, Brussels, Belgium.

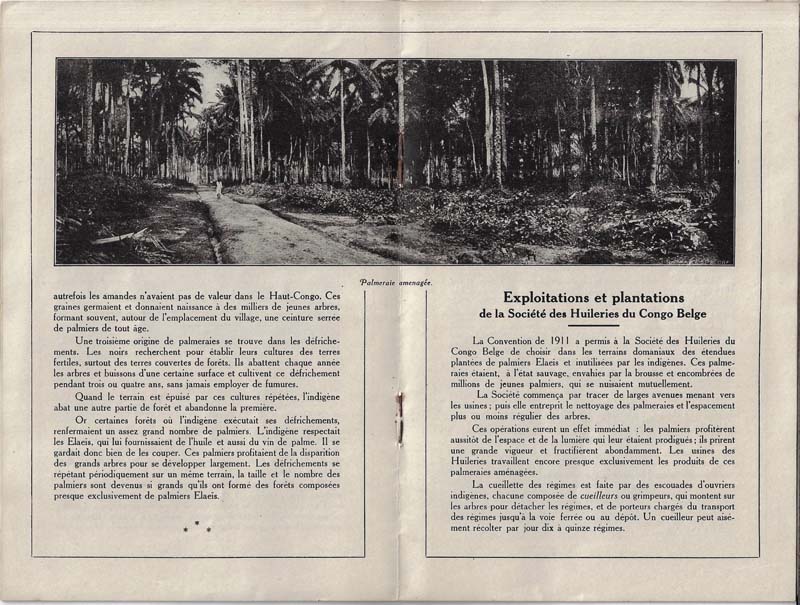

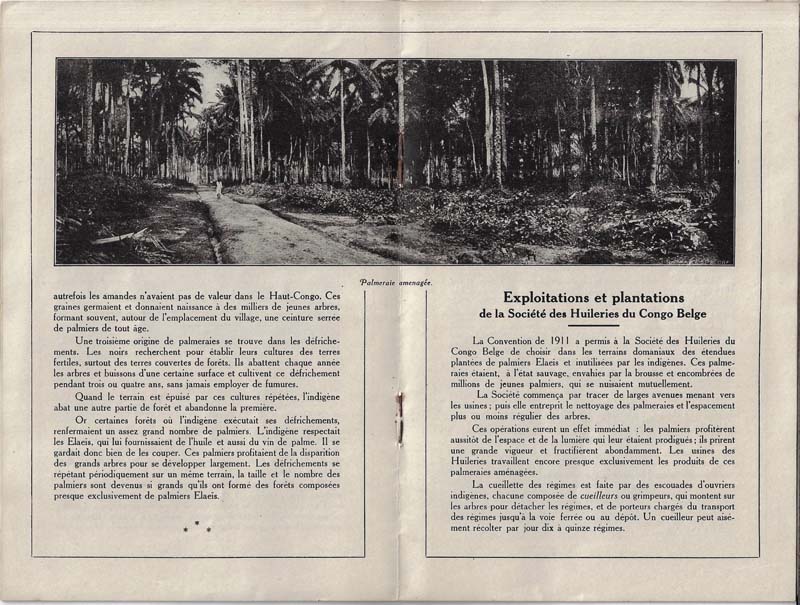

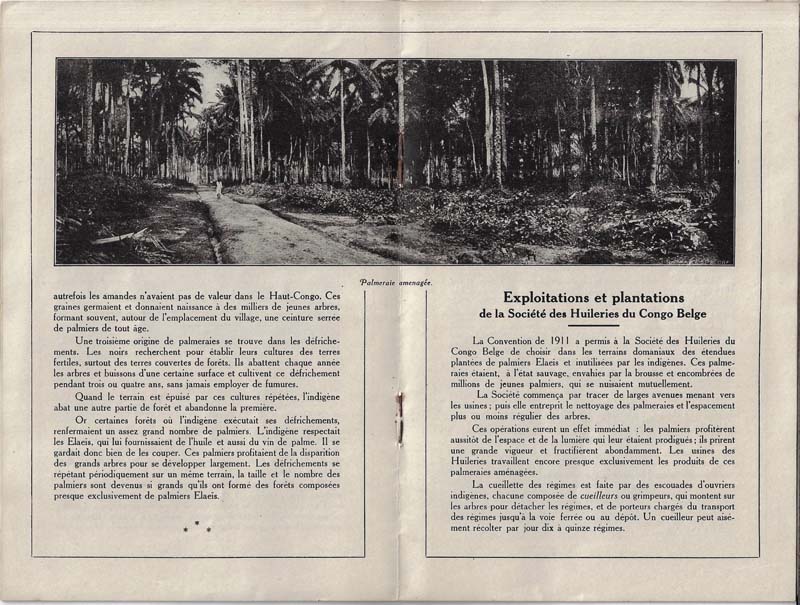

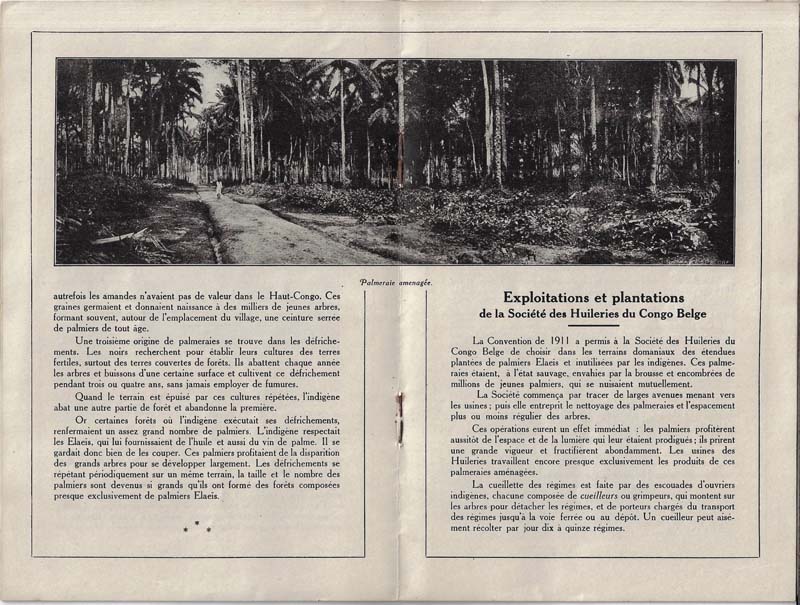

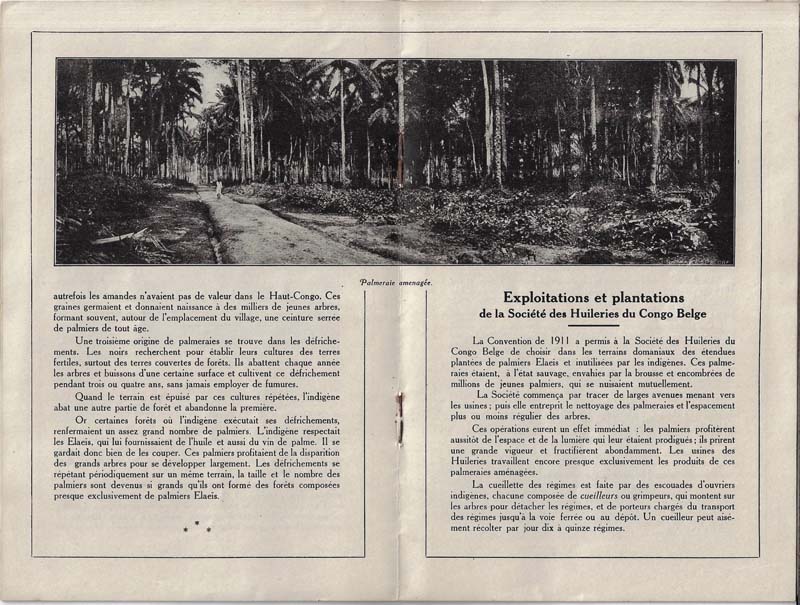

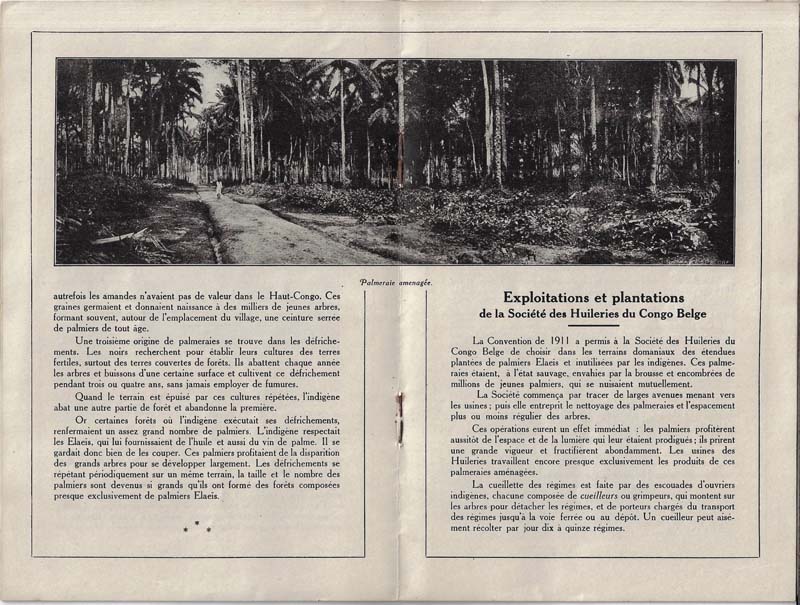

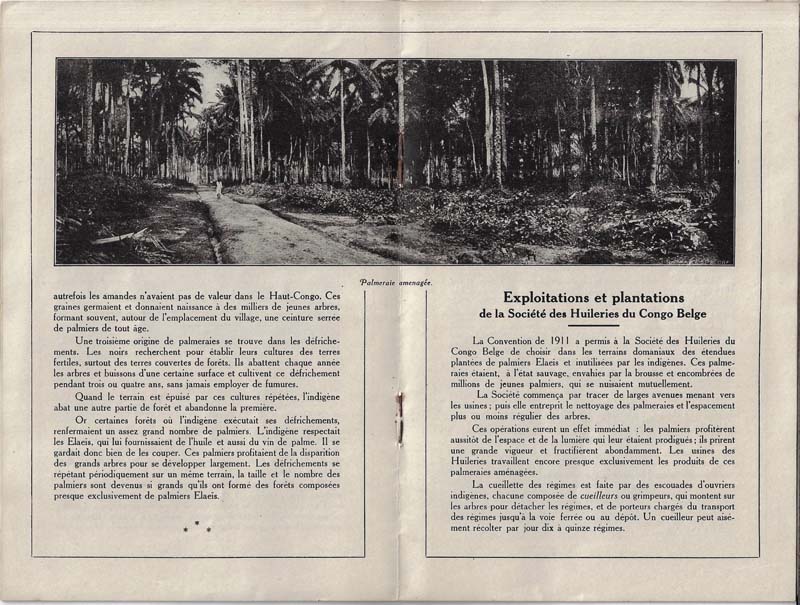

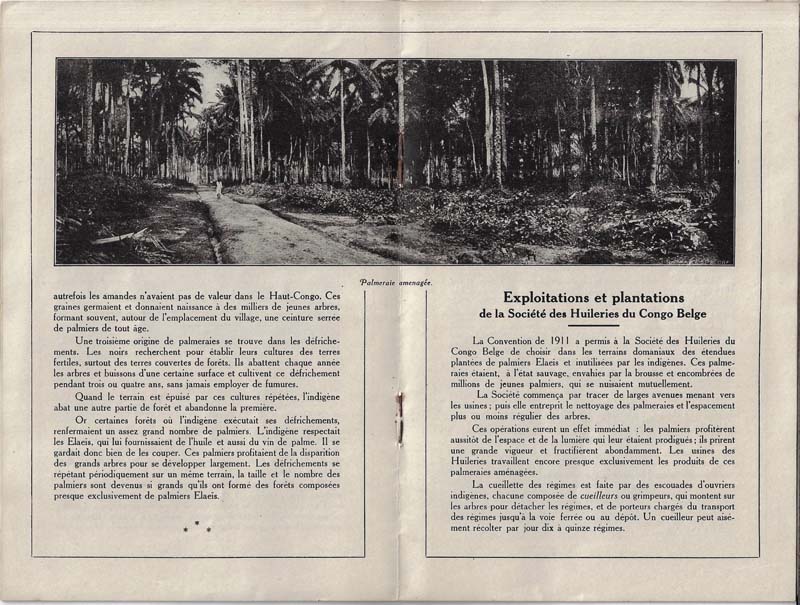

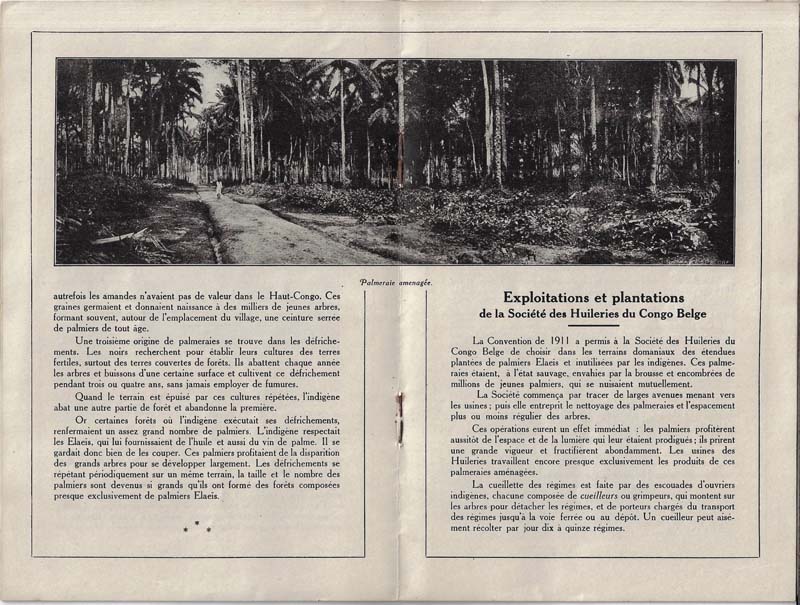

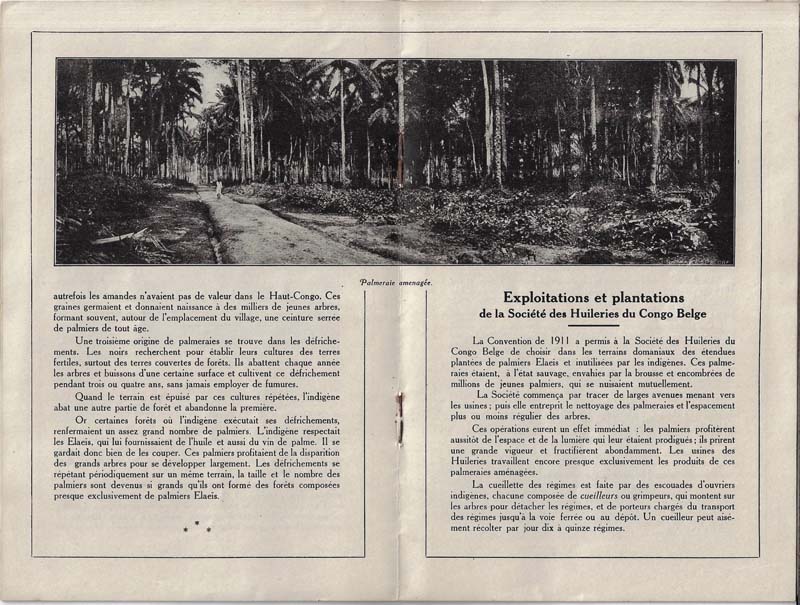

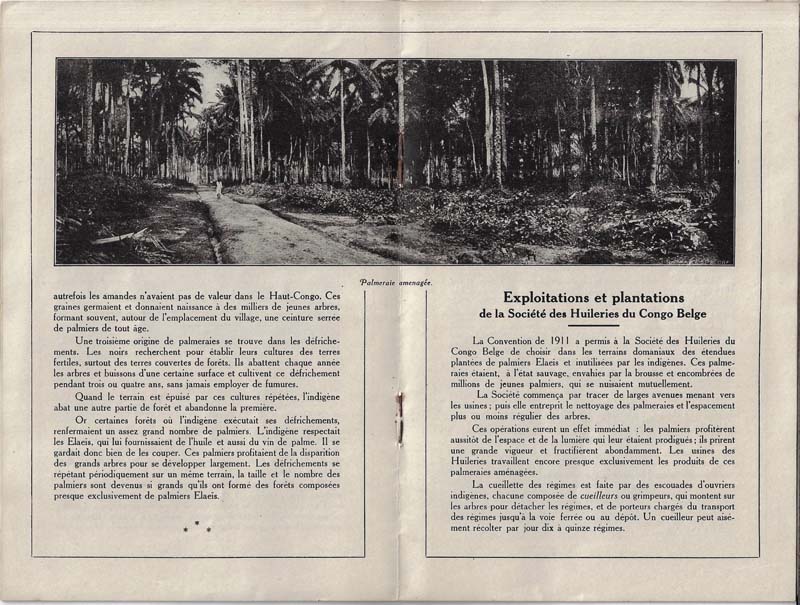

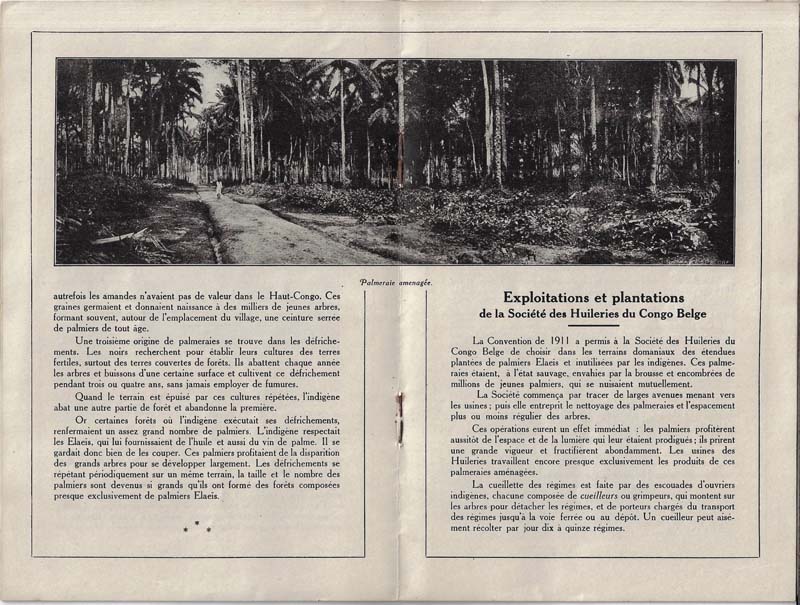

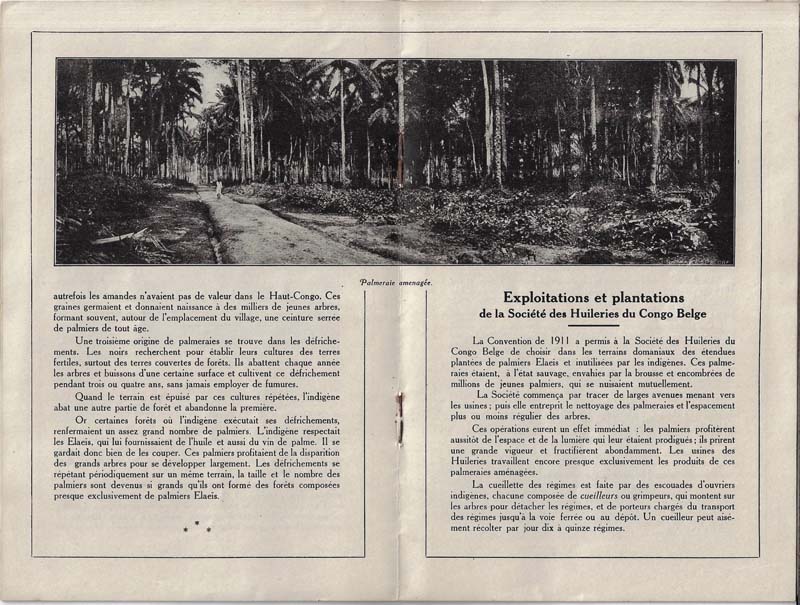

An ‘avenue’ in an oil palm plantation in the Belgian Congo, (1924) Au Pays des Palmiers, De Rycker.

During one of my frequent visits to Brussels, I decided to trace its footsteps among the city's architecture. Just steps away from the European Parliament, above the entrance of a rather nondescript office building, a stone frieze depicted the harvesting and processing of palm oil. A series of figures were portrayed in rigid poses, reminiscent of Egyptian bas-relief. At the end of the production chain, a factory worker delivers the product into the hands of a stylized Mercury, with a globe at his feet. Mercury, the god of shopkeepers and merchants, and the globe at his feet rhetorically symbolized the global aspirations of such an enterprise: gathering a natural resource from the most remote places to integrate it into the global capitalist circuit.

Indeed, if we were to follow the traces of this wandering Mercury, we would realize that palm oil has been and continues to be the intermediary in a chain of exchanges, commercial exploitations, and labor relations that have contributed to creating industrial and commercial empires around the globe. And yet, delving into the history of such agribusiness also means necessarily scratching beneath the rhetorical surface of the corporate and (neo)colonial narrative. Palm oil production and global trade have been, and continue to be, associated with labor exploitation, population displacement, abuse of the rights of local populations, and environmental degradation.

Even today, when palm oil accounts for over a third of the vegetable oil produced worldwide, its production and use are at the center of a decades-long controversy. On one hand, NGOs hold the palm oil industry responsible for environmental degradation, increasing poverty among indigenous peoples, and human rights abuses. On the other hand, independent scientists argue that the development of oil palm plantations can contribute to meeting the food needs of a growing global population and to a decline in rural poverty.

Resolving such a controversy is beyond my capabilities, but in this initial part of my journey, I glimpse the impact of this controversial agribusiness on everyday objects, public and private spaces, and natural and built environments. I sketch the material, architectural, and natural landscapes of palm oil. All of this, in one of the earliest epicenters of the surging demand for palm oil by the Western industry in the 20th century: the Democratic Republic of Congo, or simply the DRC.

Bare metal structures began to emerge since the early 1900s, protruding from the tropical vegetation background under the pressure of European colonial extractivism. Warehouses and workshops covered with corrugated iron sheets were constructed in countless locations to house the noisy machinery required to crack, press, and sterilize the reddish pulp and kernels of the palm fruits. Company towns were built to house the workers of its plantations and mills. Metal tanks to store and preserve the oil imposed their bulky silhouette in the main ports. Forests were cut and incinerated to make space for new plantations.

Kinshasa

[Linard] ––eh! l’huille de palme… palm oil, you use it for when you’re stung by ekonda. It’s an insect that doesn’t bite you but when you touch it, it gives you irritation to the skin. You put palm oil on it, and it helps. It’s good for the skin.

Sometimes you use it on the newborn babies because their skin is delicate. But it’s less common now.

And then, of course, you can’t make a good pondu [a popular stew made of pounded manioc leaves] without palm oil. And the tchaka madesu too. Manioc and beans.

Isn’t palm oil less used nowadays for food? – I ask to Linard – because of all the other vegetable oils that are imported. Sunflower, and, you know, all the rest…

––I’m not sure about that. Palm oil is a tradition here.

We're having this conversation while sipping a sucré at rond-point Luputa in Bandal, short for Bandalungwa, a neighborhood of Kinshasa, the capital city of the DRC. Some of the most meaningful encounters I've had in Kinshasa happened here, and Linard is a friend. His family owns a small palm oil plantation outside the city. I ask him some questions and explain how different the perception of a product so everyday for him is outside the continent we are on, and he nods in agreement.

Rond-Point Luputa, perhaps a strange place to ask this kind of question, is exactly what the name suggests: a roundabout. Definitely not the busiest crossroad in Kinshasa, a city of 20 million inhabitants, where the traffic and noise are so overwhelming that writing about it sounds redundant. During the day, cars are parked in the middle of the roundabout and moto-taxis circulate on the perimeter. But during the night, it becomes one of the busiest spots in the neighborhood as the parked cars are moved, the space is covered with tables, and the roadside gets filled with grilling boards and chikwanga sellers.

Bandal is informally called ‘Paris,’ but the sparse neon signs in Luputa say ‘Hotel États-Unis’ or ‘Cina Grill,’ contrasting with the pitch-black, largely electricity-less nights of Kinshasa. This disjointed whirlwind of geographical references brings me to mind the globe at the foot of Mercury, in that frieze I saw a few years ago in Brussels. And yet here in Kinshasa, this rhetoric of global aspiration seems much more amusing.

Palm oil jerrycans at the Matete market, Kinshasa

A few days later, the loads of yellow jerrycans that I see passing by on the street attract my attention. I go to visit the Matete market, one of the largest in the city. In a sector of this large, mostly open-air market, palm oil producers from Bas-Congo, as the now Kongo-central province is still called, or from Bandundu crowd with their trucks loaded with the plastic containers. The palm oil sector is just a space between buildings with controlled access, and wherever you look, everything is yellow-orange, stained with mud.

The overseer of one of the warehouses where jerrycans are gathered explains to me that producers come to them, unload their trucks, and wait until all their produce is sold, even if it means waiting for a week or two. They lie on the black muddy soil, using manioc leaf bags as pillows, under the shade of a simple porch made from metal sheets leaning against a cement brick wall. When all the oil is sold, they retrieve their containers and return to where they came from.

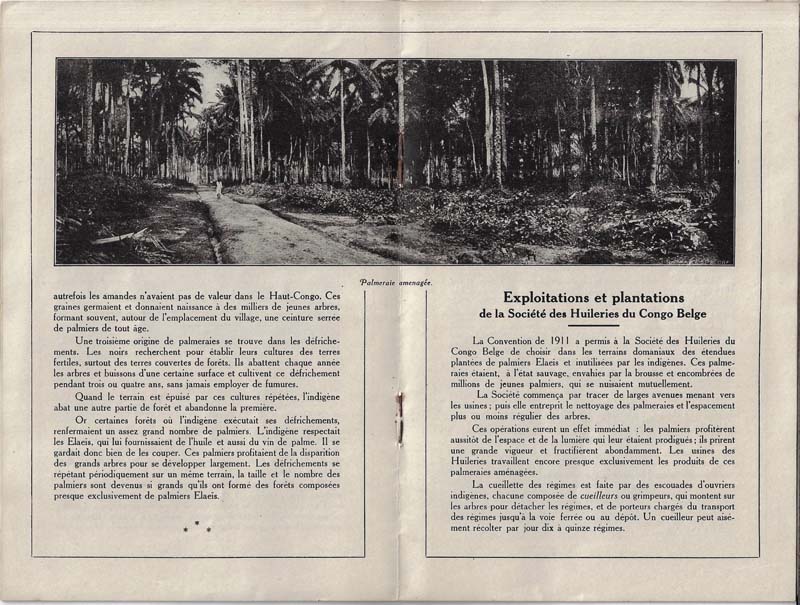

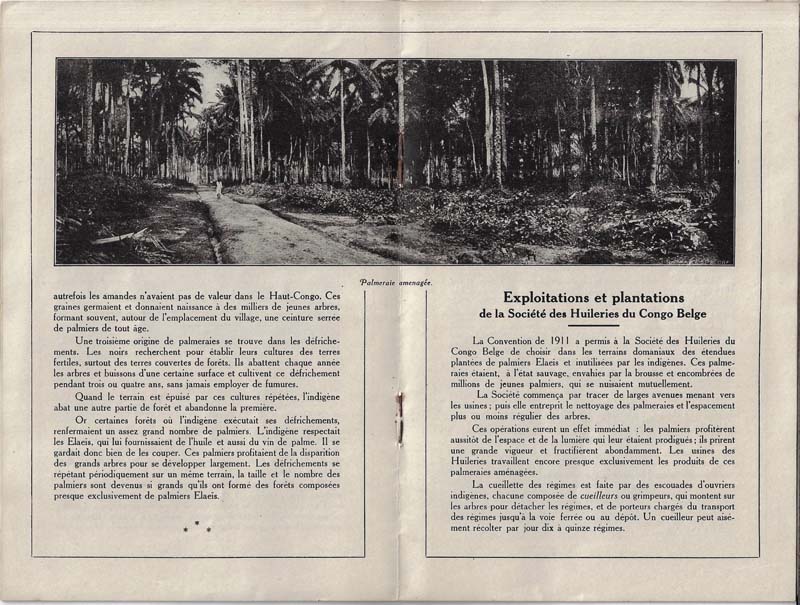

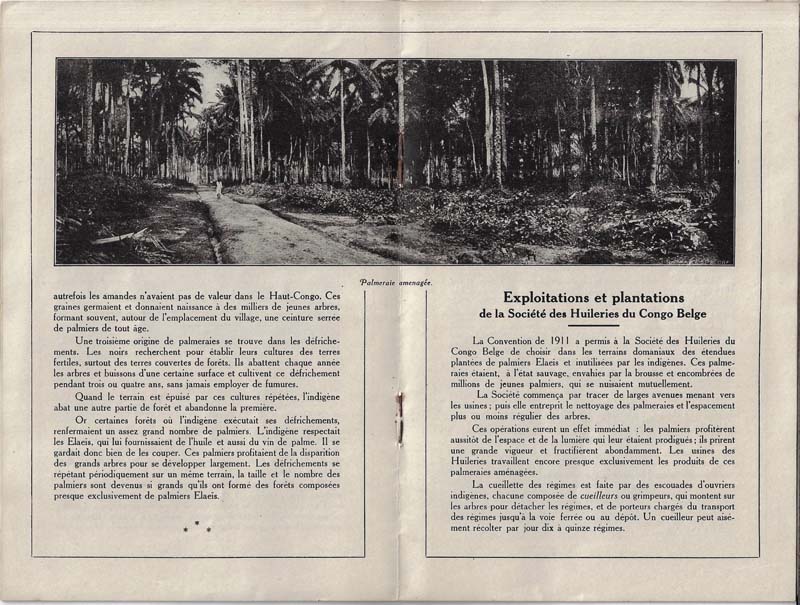

I'm also explained that the producers from Bas-Congo exploit artisanally, without machinery. All processing, from extraction to filtering is done manually in what are called palmeraies naturelles, natural palm groves, clusters of oil palm scattered in the forest. And while these are de facto cultivated, they defy the appearance of orderly arranged rows of plants that characterize plantations. On the contrary, producers from Bandundu exploit old and semi-abandoned plantations. But the lack of maintenance and the old age of the plants make them less productive.

His opinion is blunt: the quality of the produce from Bandundu’s old plantations is too low to be used as a food product and is generally sold to Marsavco, the only large soap-making factory left in Kinshasa and the heir to Huileries du Congo Belge, the business empire whose building still stands today in the institutional quarter of the European capital.

Satellite view of 'Camp PLZ,' the current name of the residential quarters for workers of the Huileries du Congo Belge, which was renamed Plantation Lever au Congo/Zaire. While the original barracks have been largely modified with additional volumes, the original arrangement is still clearly visible from above.

Lusanga

The produce from Bandundu in the Matete market came from a plantation complex that, at least until the era of Mobutu, was centered around a location known as Lusanga, and during the colonial period, as Leverville. 'Lever' - 'ville', named after William Lever, the founder of Huileries du Congo Belge and Unilever. As an African counterpart to the enlightened paternalism embodied by Port Sunlight, the company town founded by Lever on the outskirts of Liverpool, Leverville was meant to become the tangible symbol of the progress that European capitalism could bring to the heart of the Congolese forest. [i]

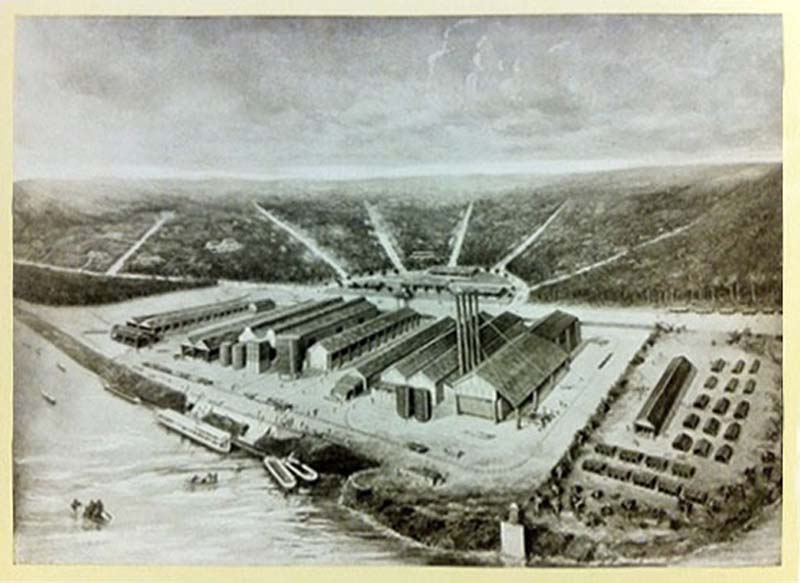

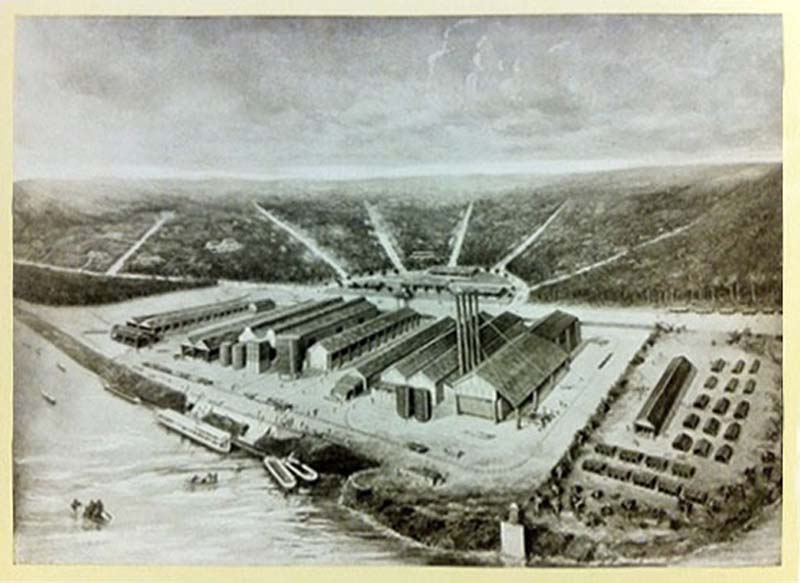

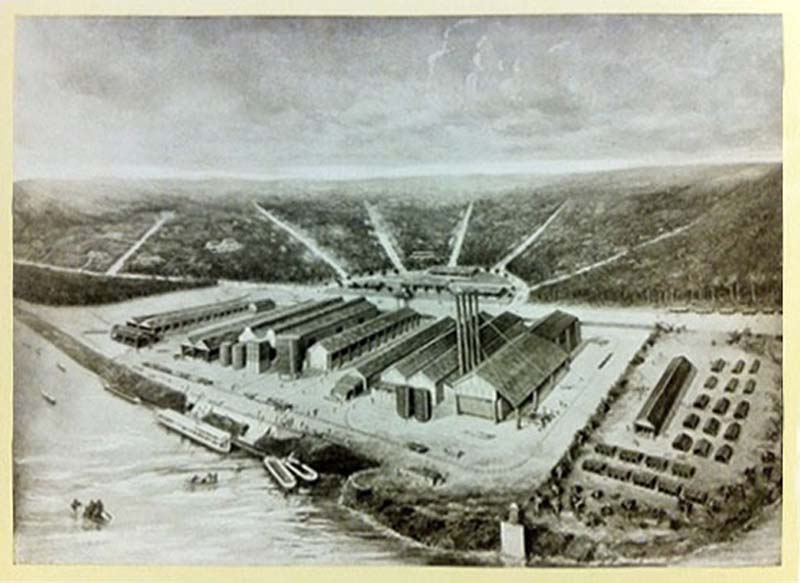

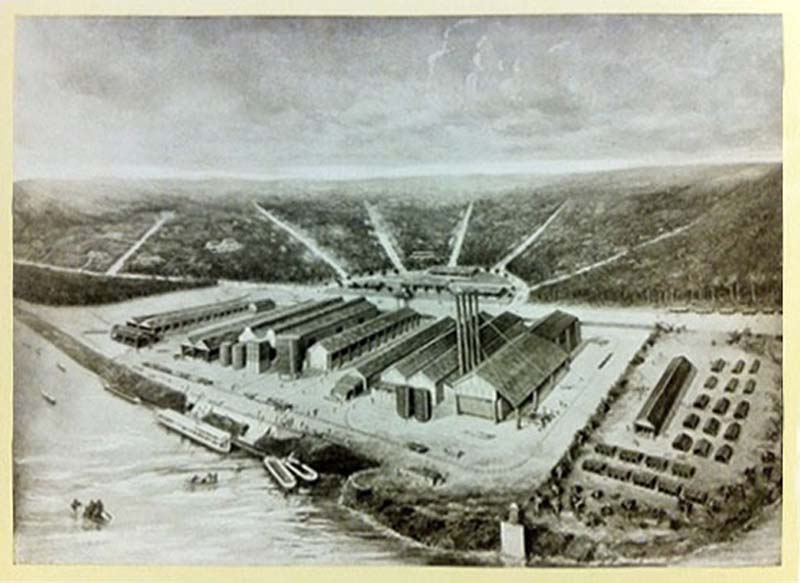

The settlement hosted one of the five palm oil plantation headquarters in the then Belgian Congo, as guaranteed by the agreement between Lever and the colonial government for the newly formed company. It was founded in 1911 when a small group of technicians sent there by the company landed at the confluence of the Kwilu and Kwenge rivers and laid out its main axes according to a symmetrical scheme of avenues stemming from the river docks. These avenues continued fading into the horizon and seemed to symbolize the propagation of progress from the mill towards the untouched forest.

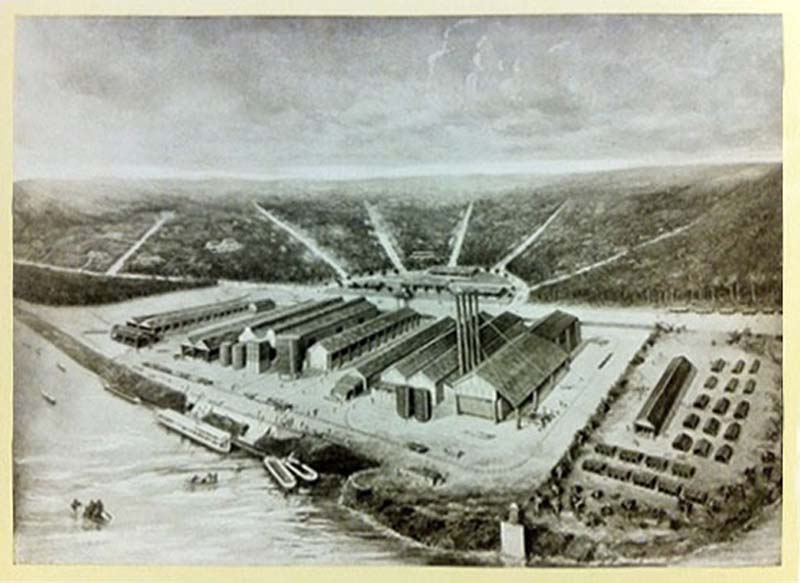

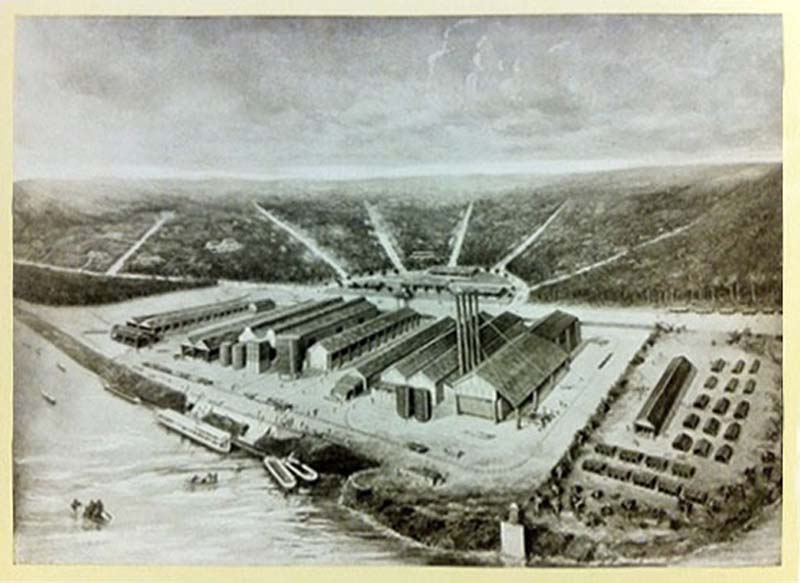

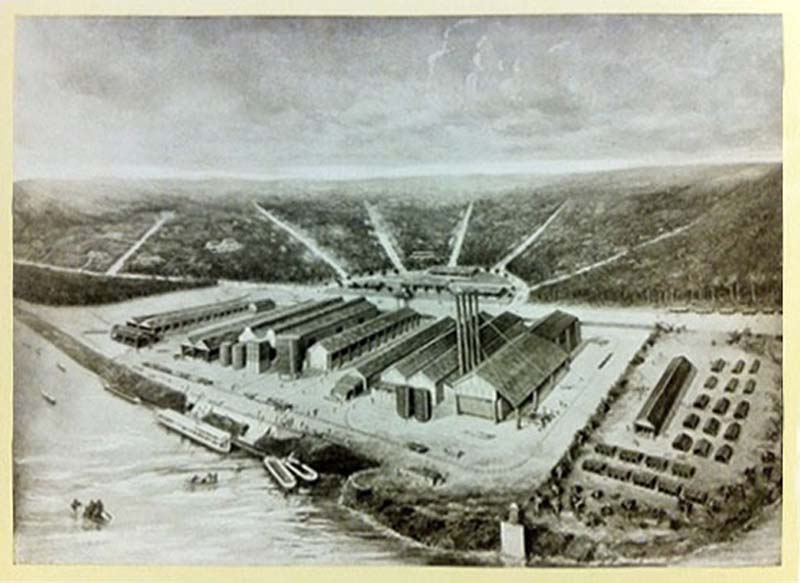

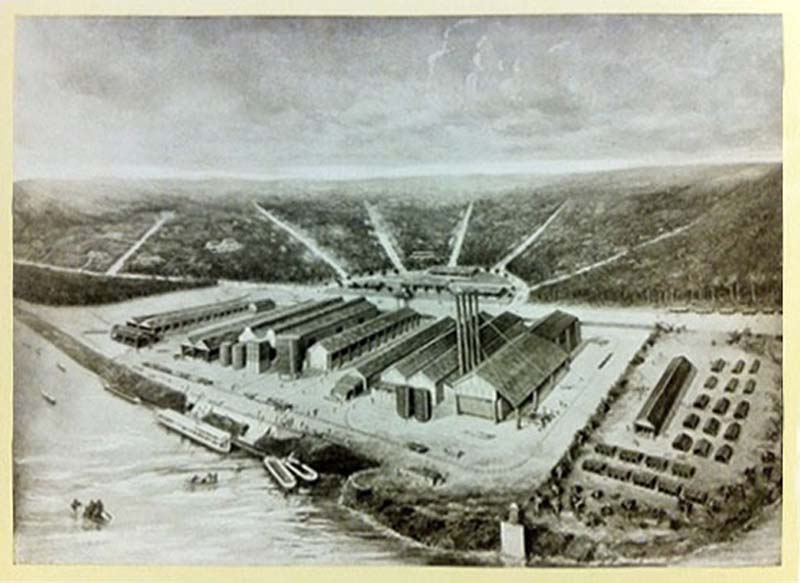

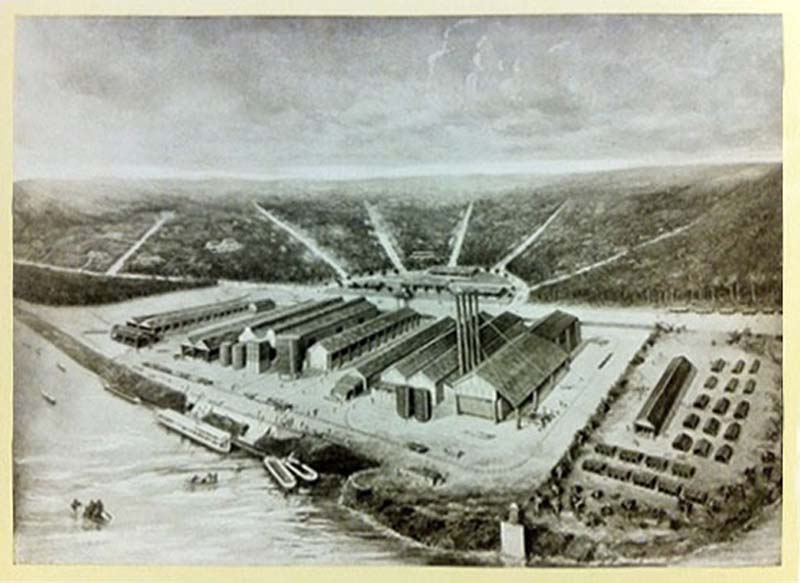

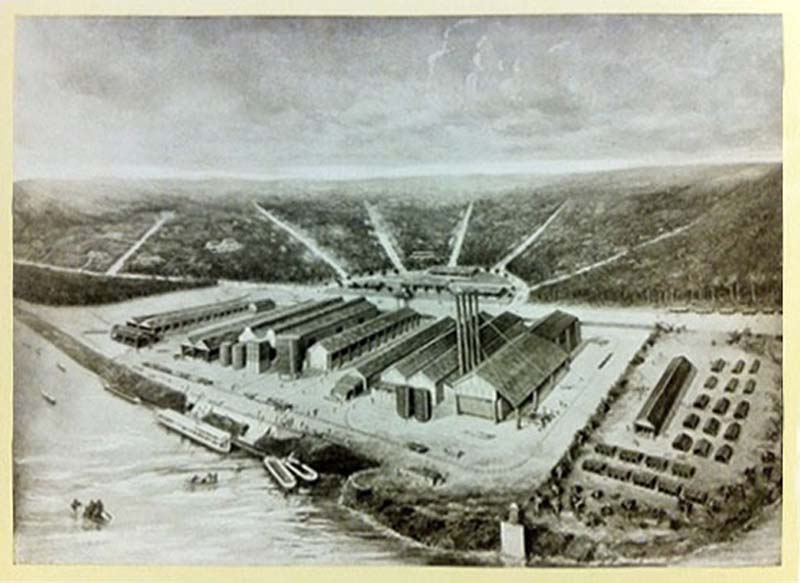

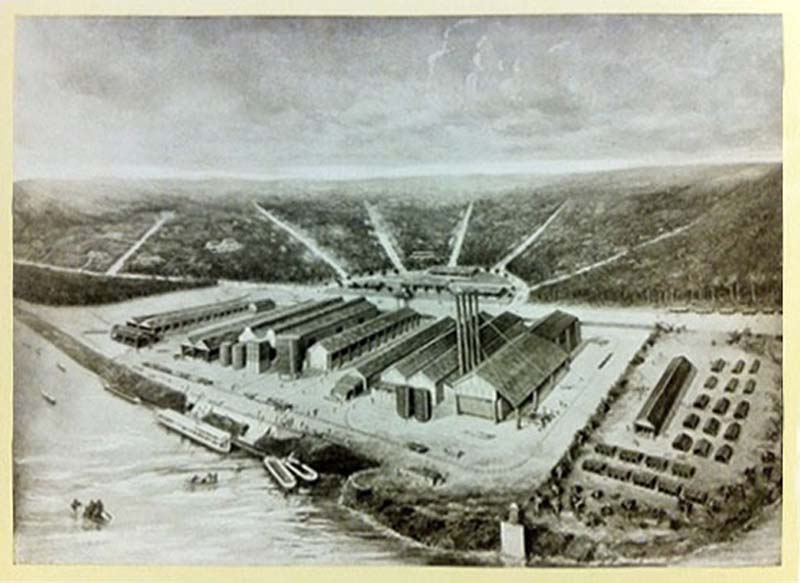

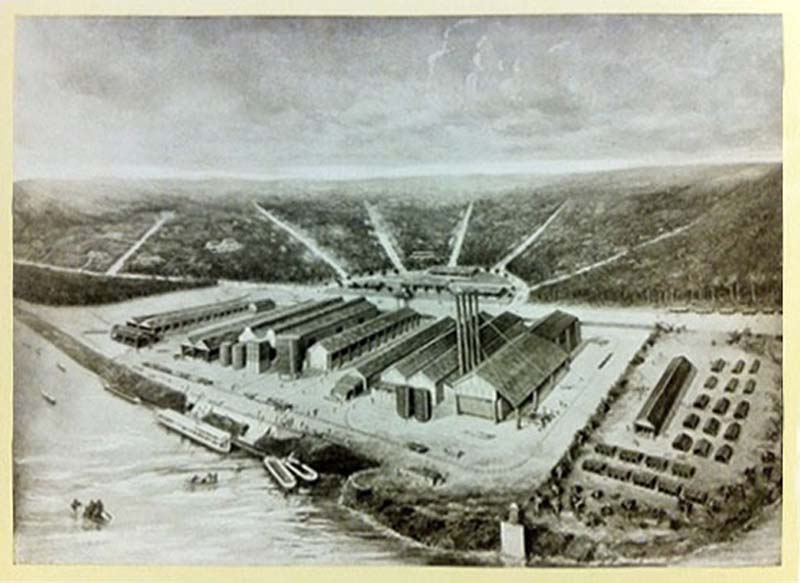

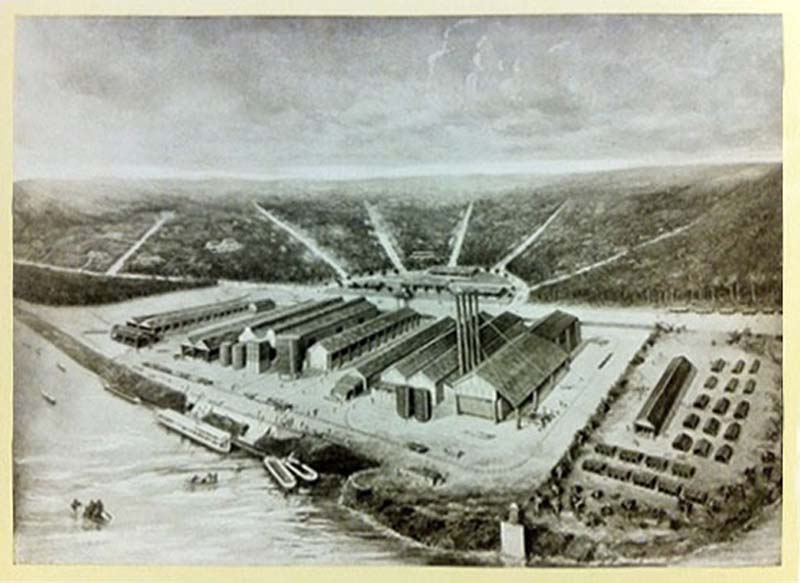

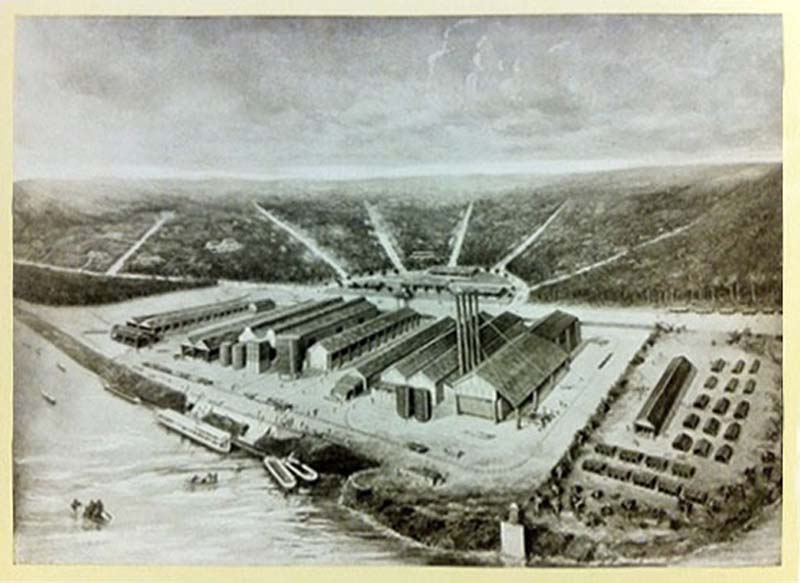

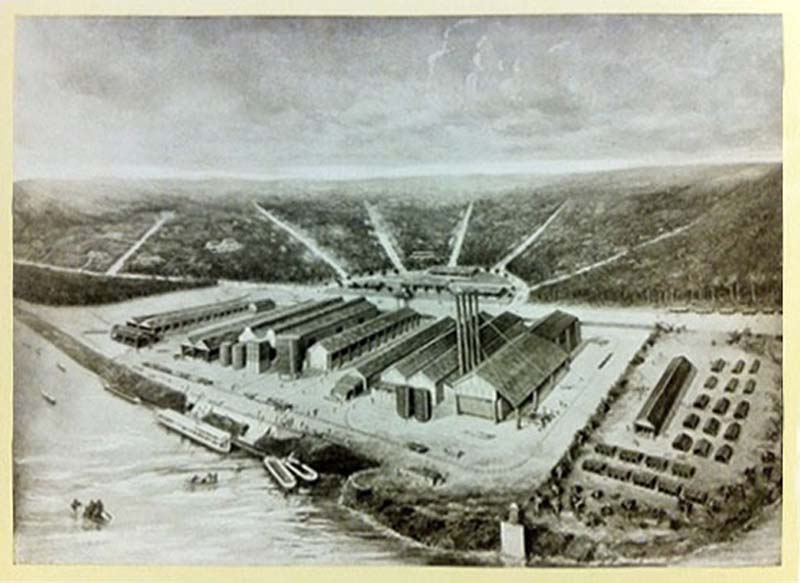

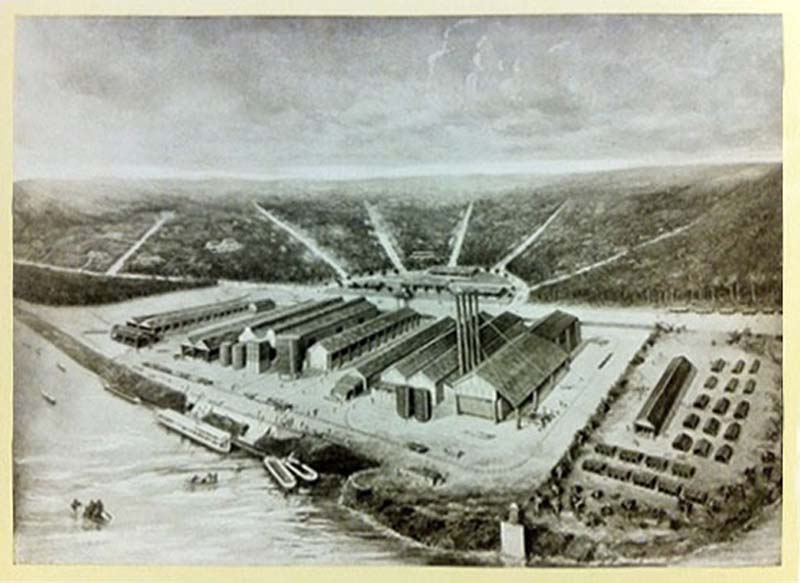

Depiction of Leverville’s docks. The avenues fading in the forest are visible in the background. https://autoitaliasoutheast.org/rwba/interior-ecosystems-kristin-luke-employee-workshops-where-objects-are-fabricated/

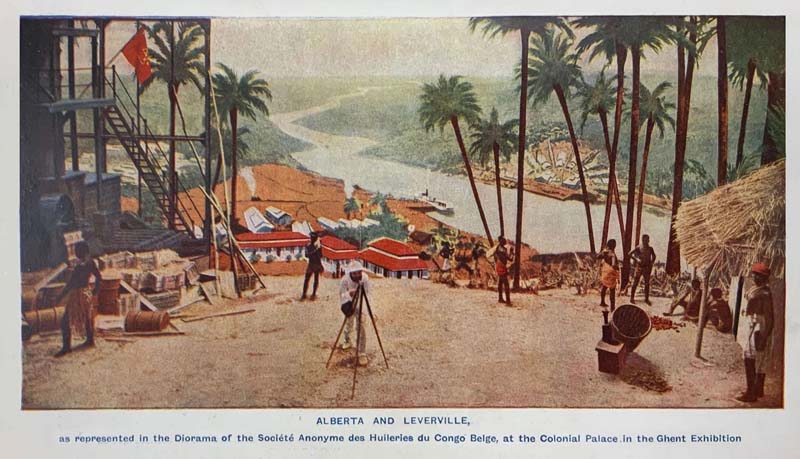

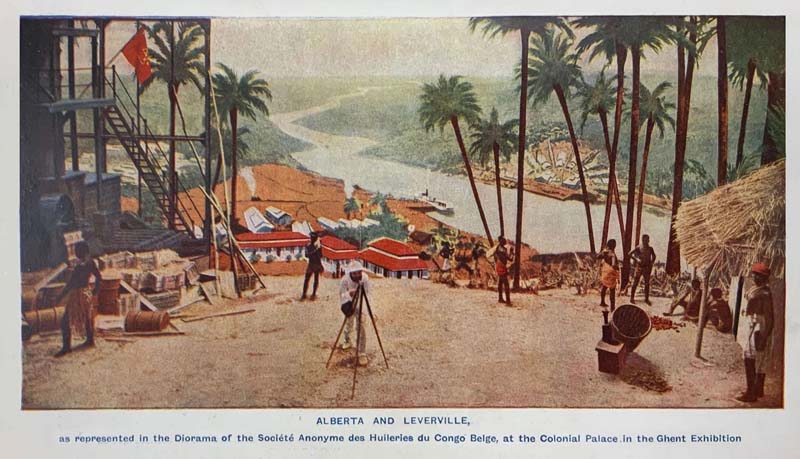

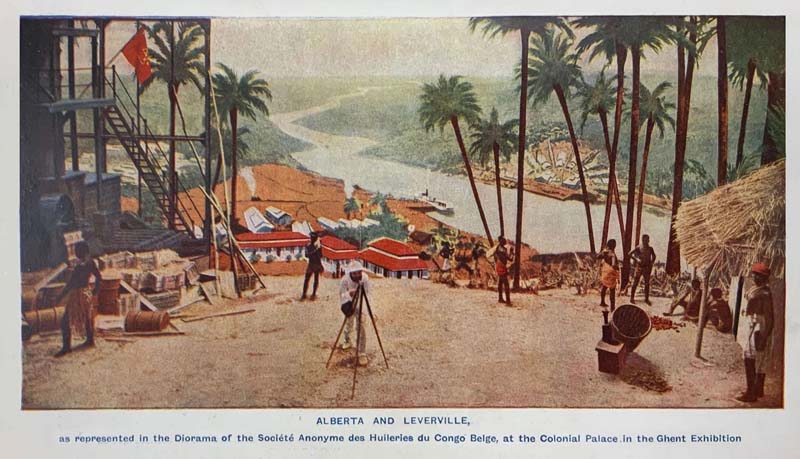

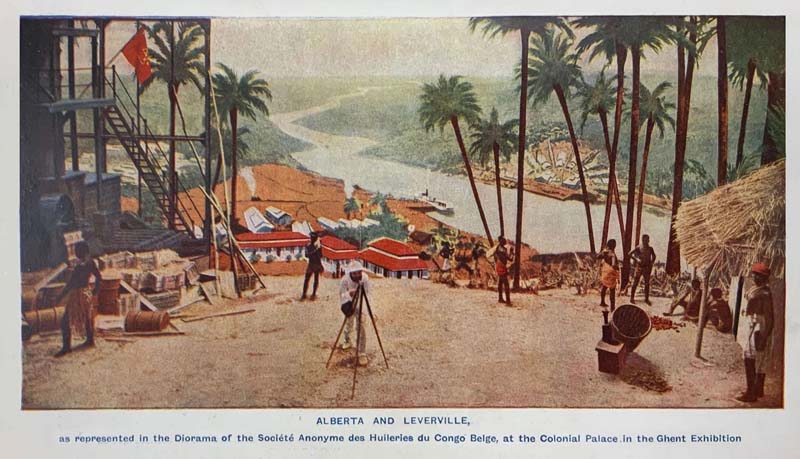

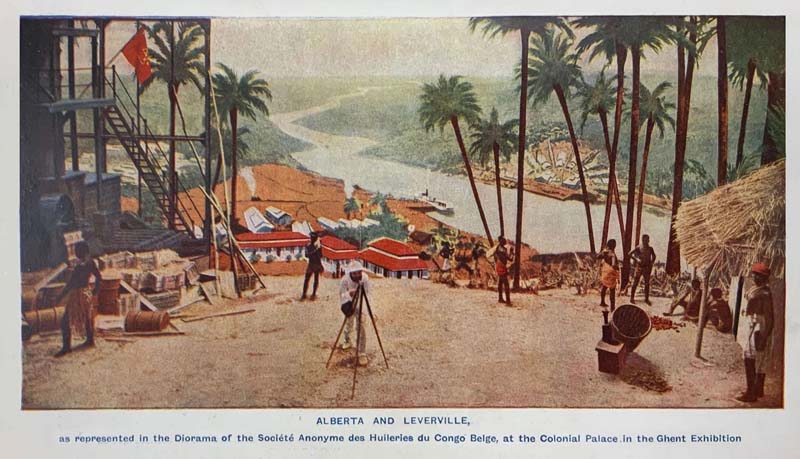

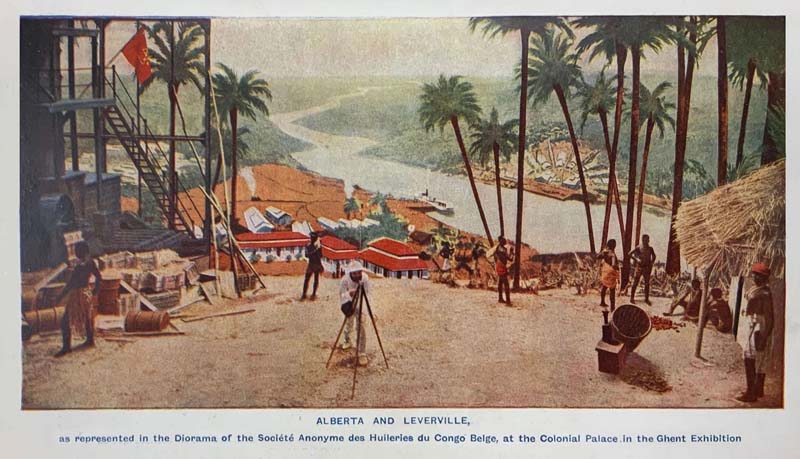

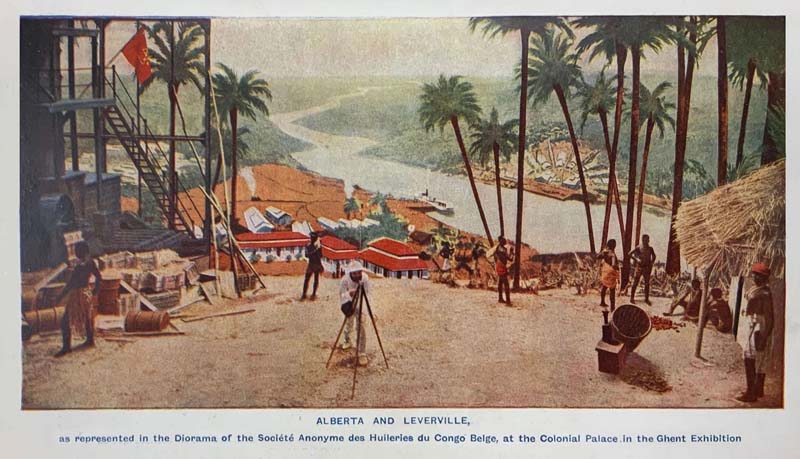

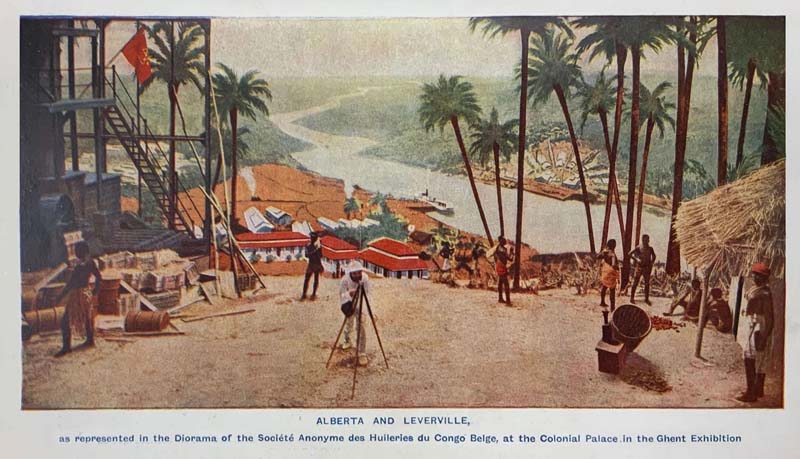

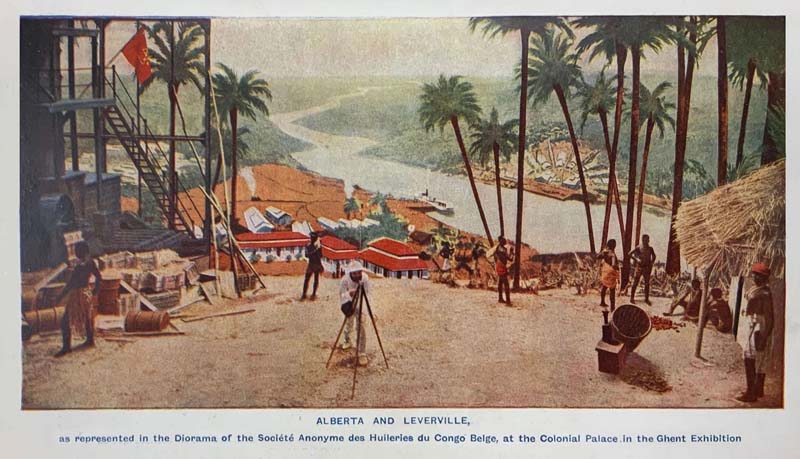

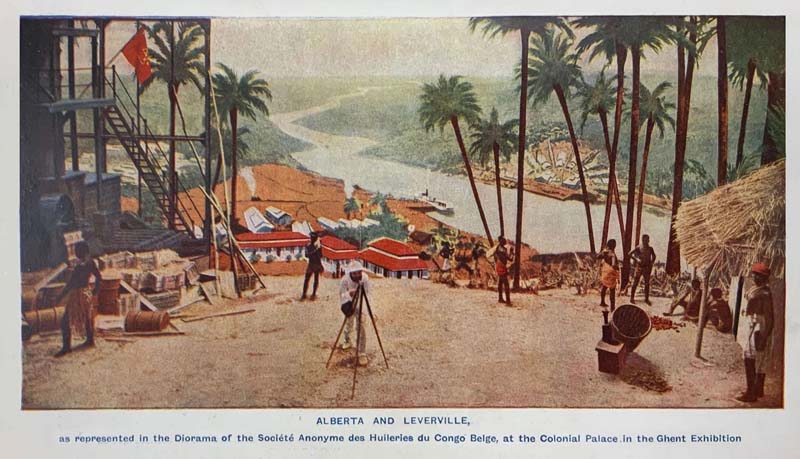

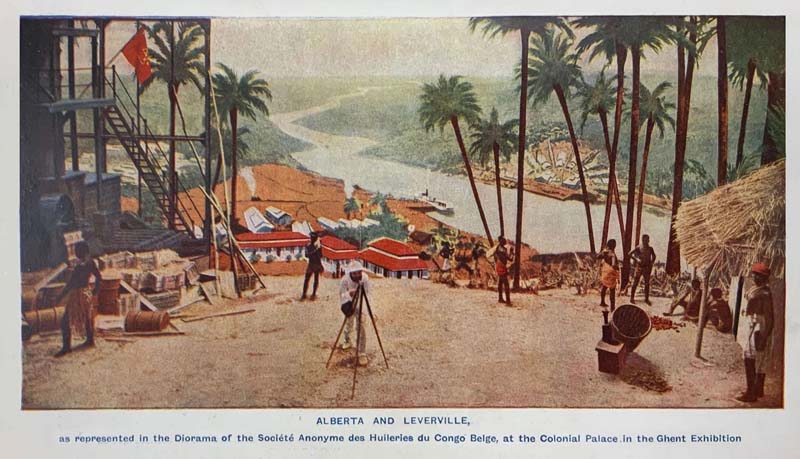

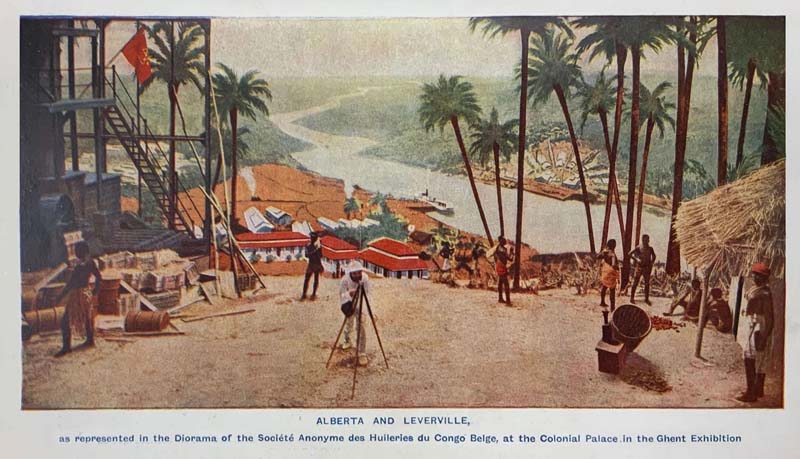

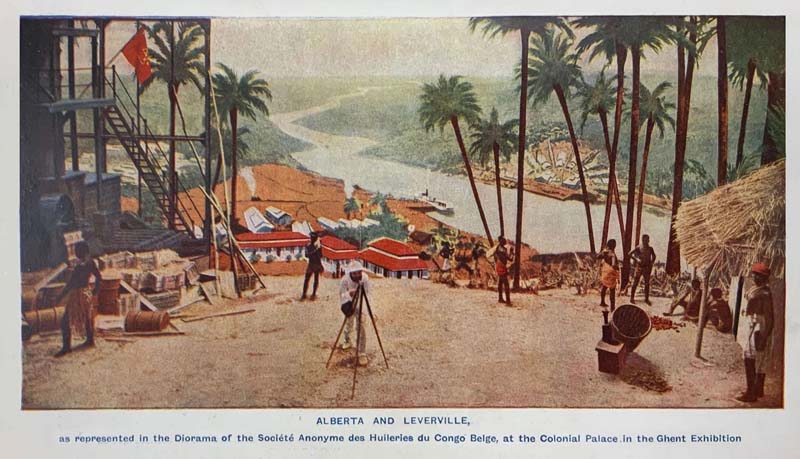

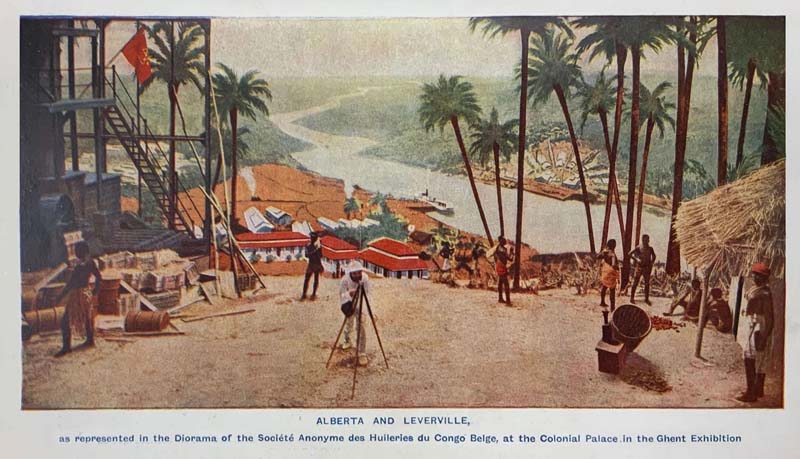

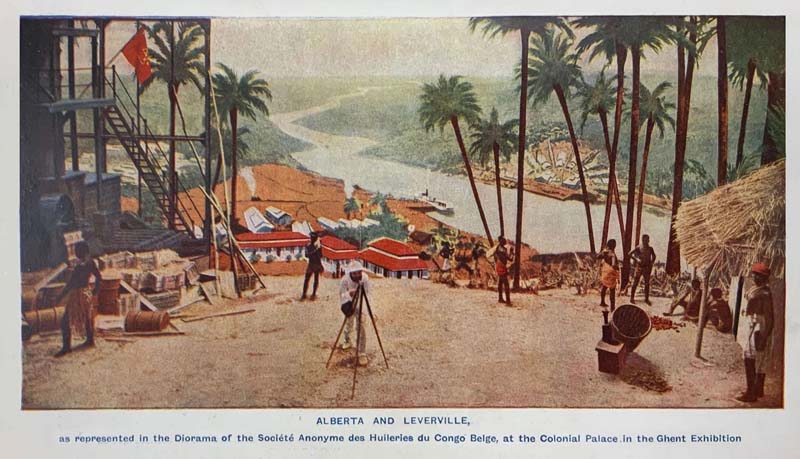

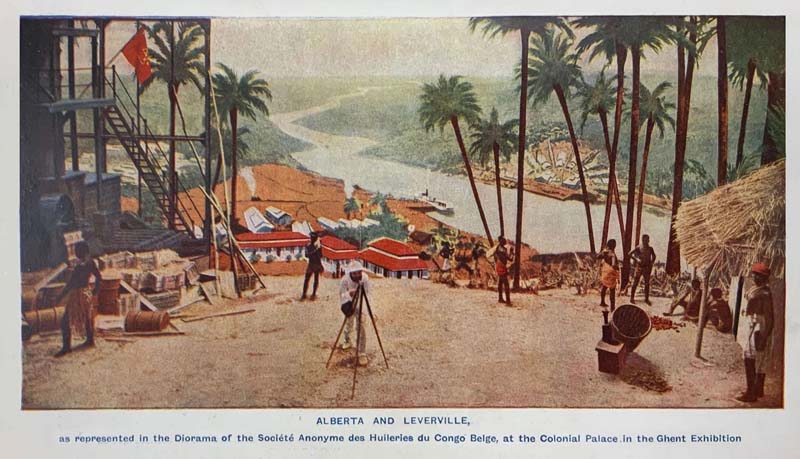

Alberta, in the foreground, and on the opposite side of the river, Leverville, two of the plantations owned and managed by HCB, as represented in a diorama for the Belgian Colonial Palace at the 1913 Ghent International Exhibition. In reality, the two plantations were thousands of kilometers apart. (Source: Progress magazine, Issue 14, p.116).

According to the romanticized accounts from the pages of one of the company magazines, which tells the story of the foundation of Leverville with all the exoticizing tropes of colonial literature, the settlement was founded on a "splendid site [which] rises in a slight slope from the river toward the interior, and is covered with magnificent palm trees laden with fruit." [ii] These diaries describe how initially, a group of over 40 laborers worked on clearing the land and constructing two houses and a native hangar. Within a month, they had cleared "more than sufficient ground for the needs of Leverville in the near future." [iii] The journals further recount the initial travels of functionaries in the Lusanga area, praising the natural riches of the region. They describe it as having "park-like, bright, grassy spaces on undulating hills, with clumps of palm and wood," and note the presence of oil palms extending for miles inland. [iv]

To tell the truth, to an eye not accustomed to agronomy like mine, such richness of palm oil went unnoticed. Or perhaps my perspective is shaped by the fact that, starting in the 1920s, the company’s own technicians realized that this natural abundance was mostly a mirage. But from the vantage point of the hill where the European quarters of Lusanga were installed, you can see the undulating landscape enclosed by the confluence of the two rivers. And the scenery is indeed magnificent.

View of the Kwilu river from Lusanga

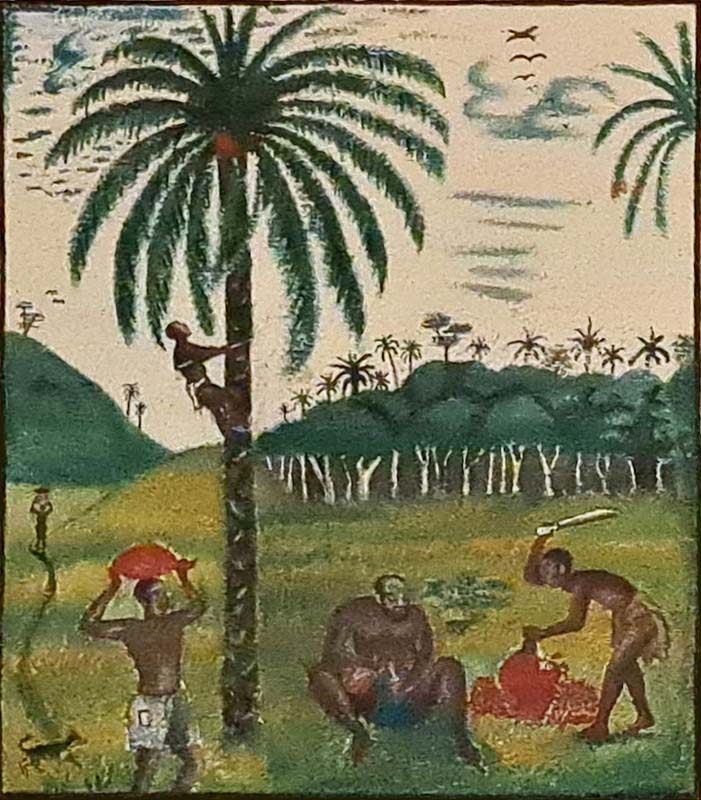

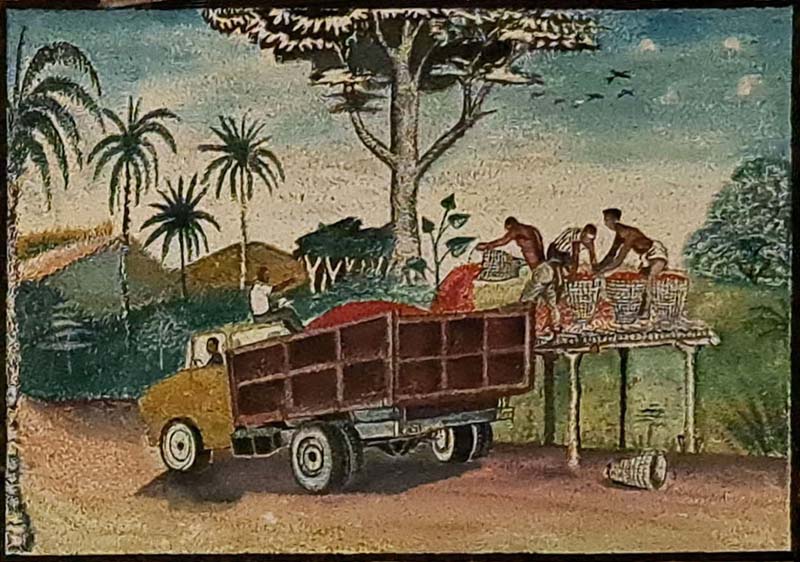

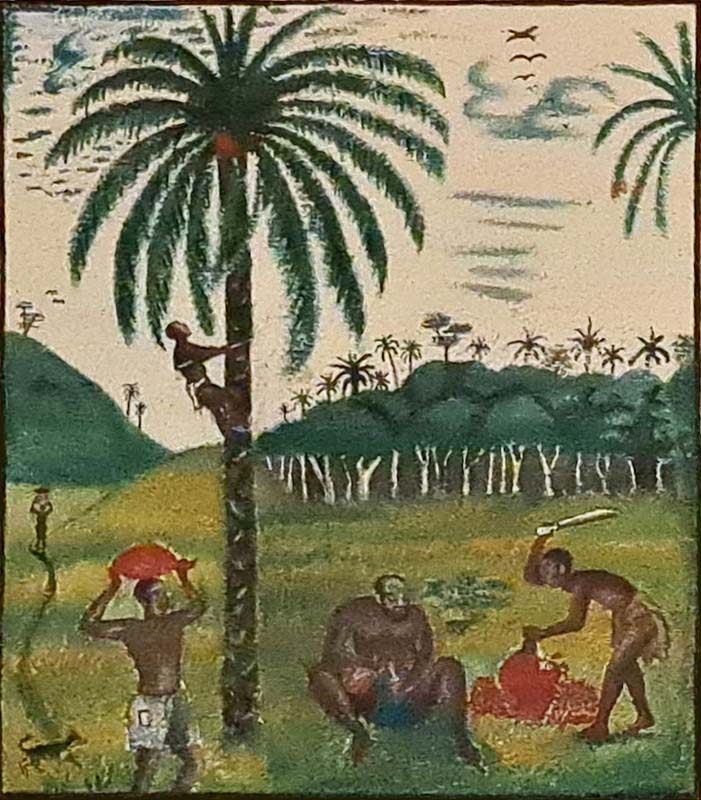

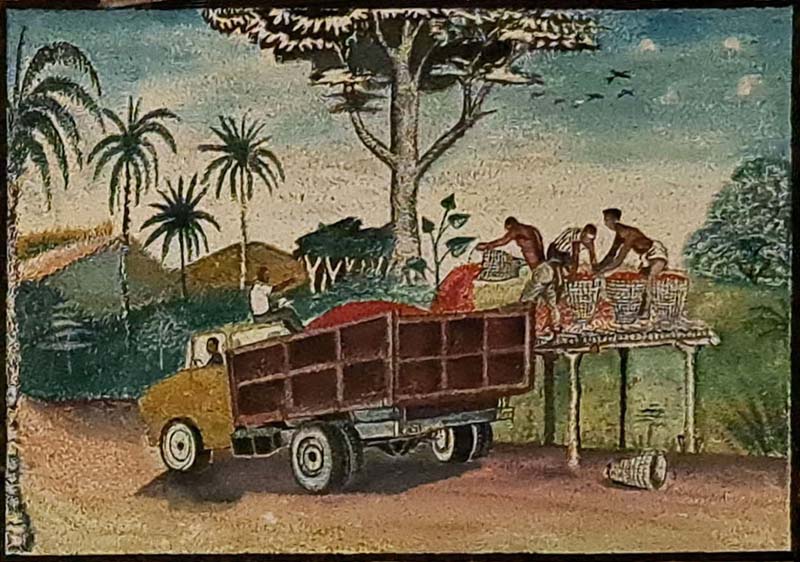

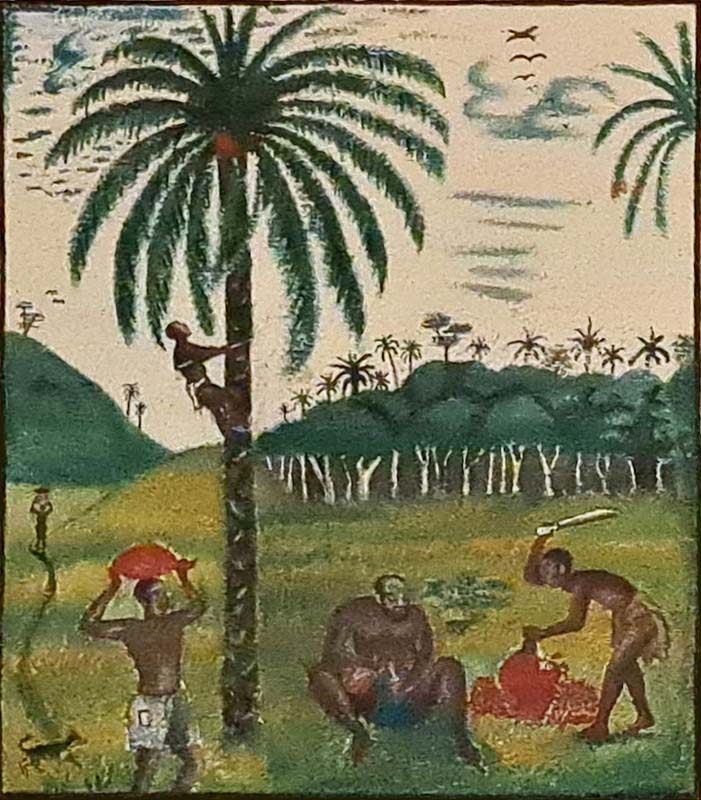

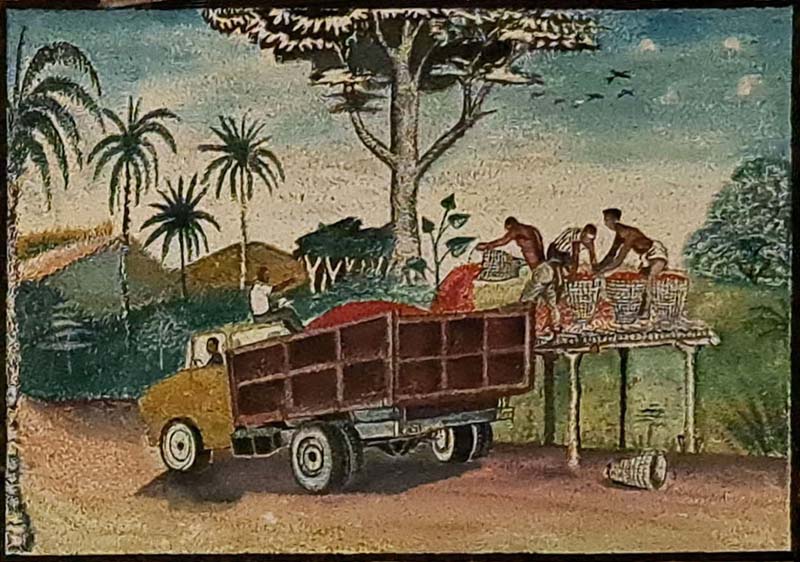

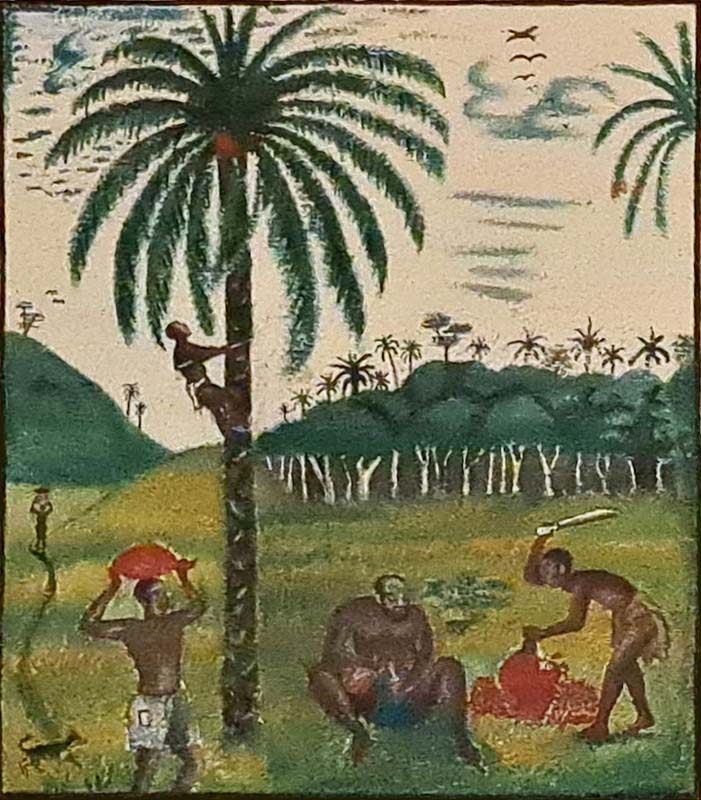

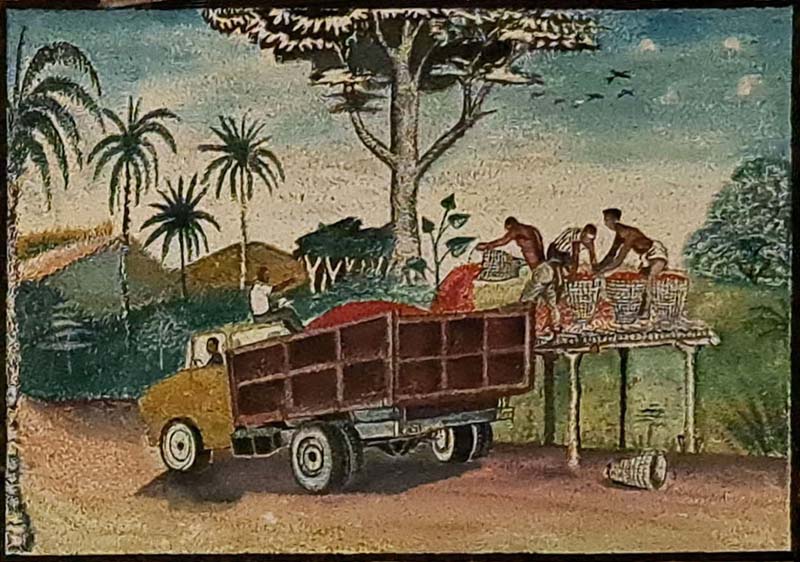

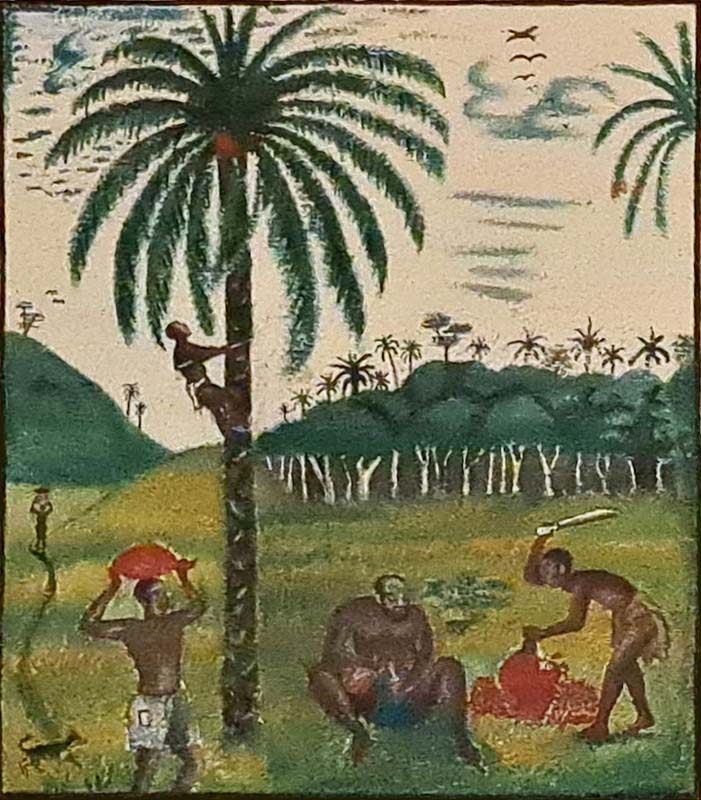

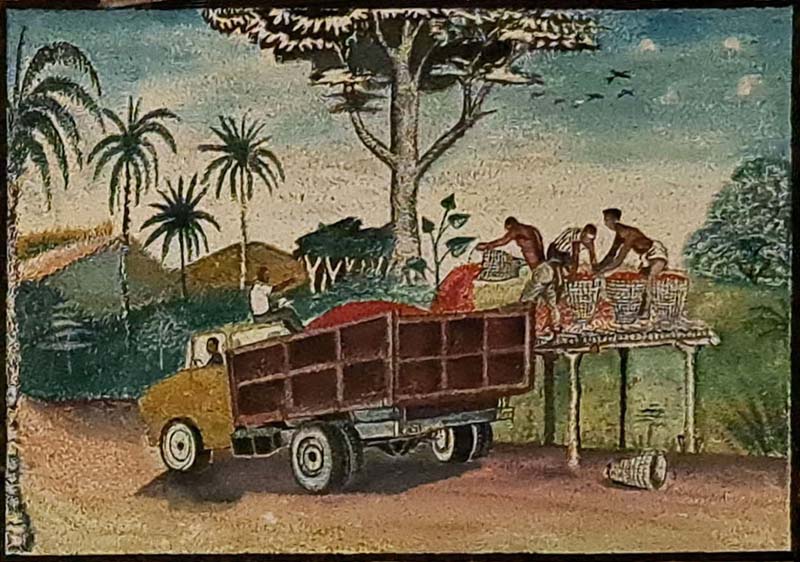

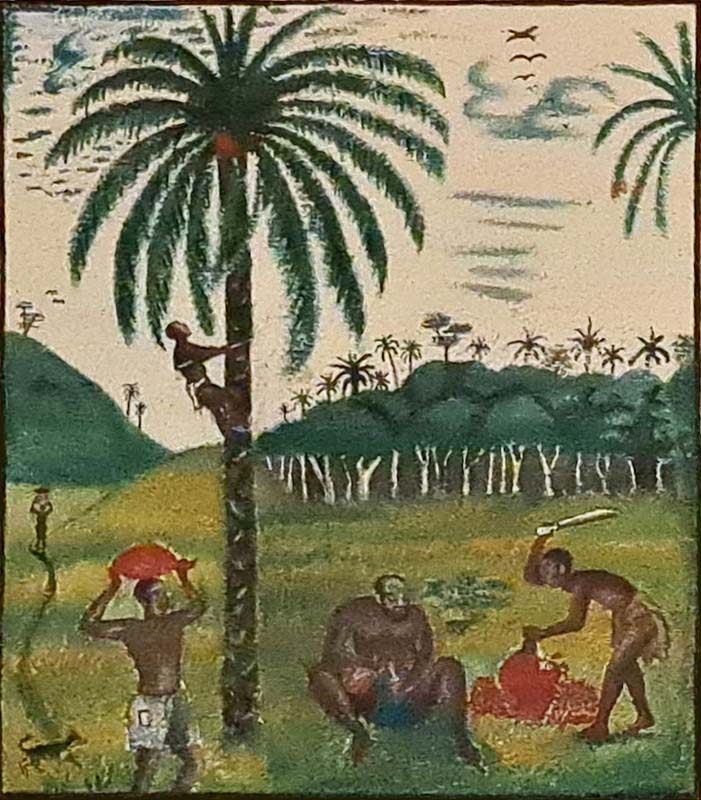

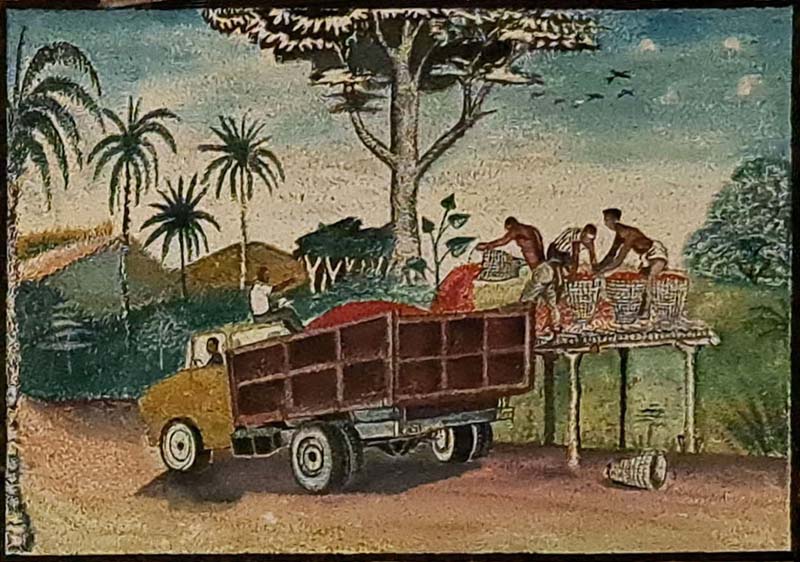

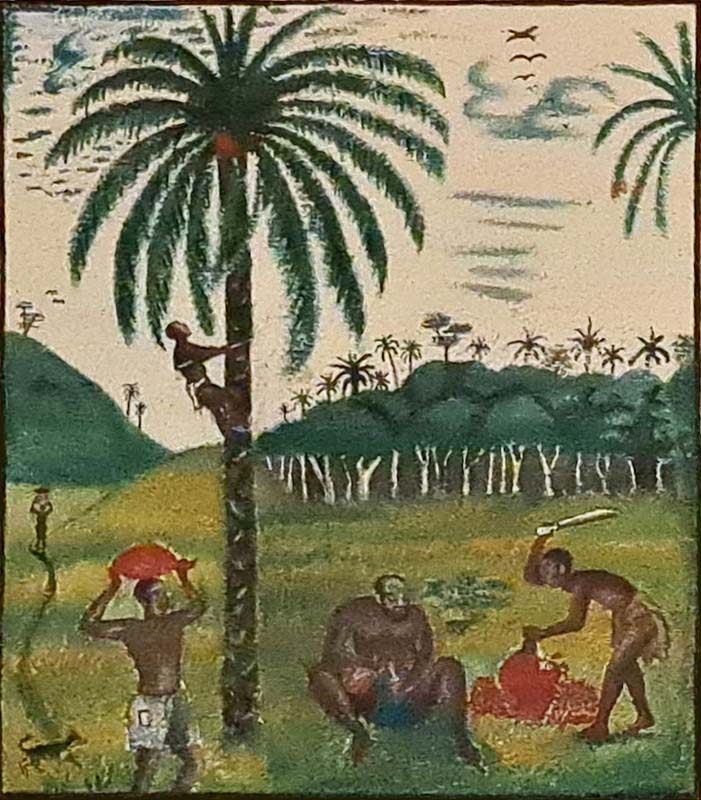

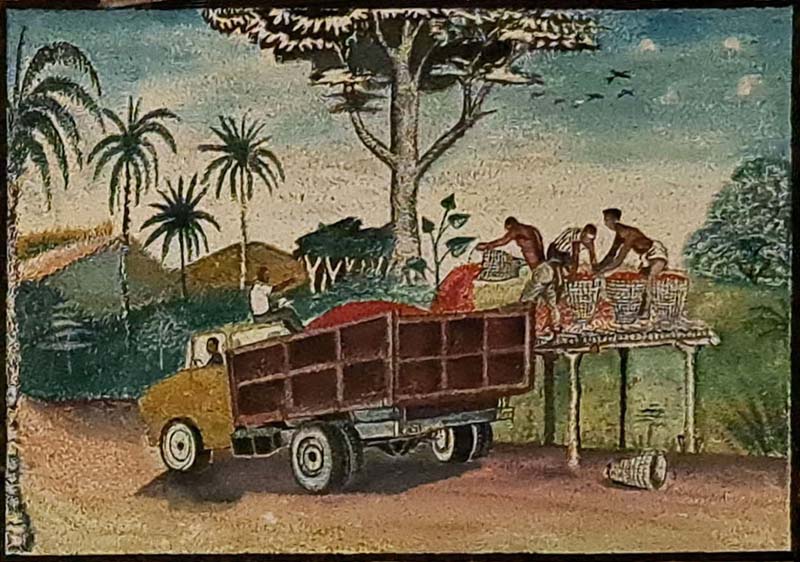

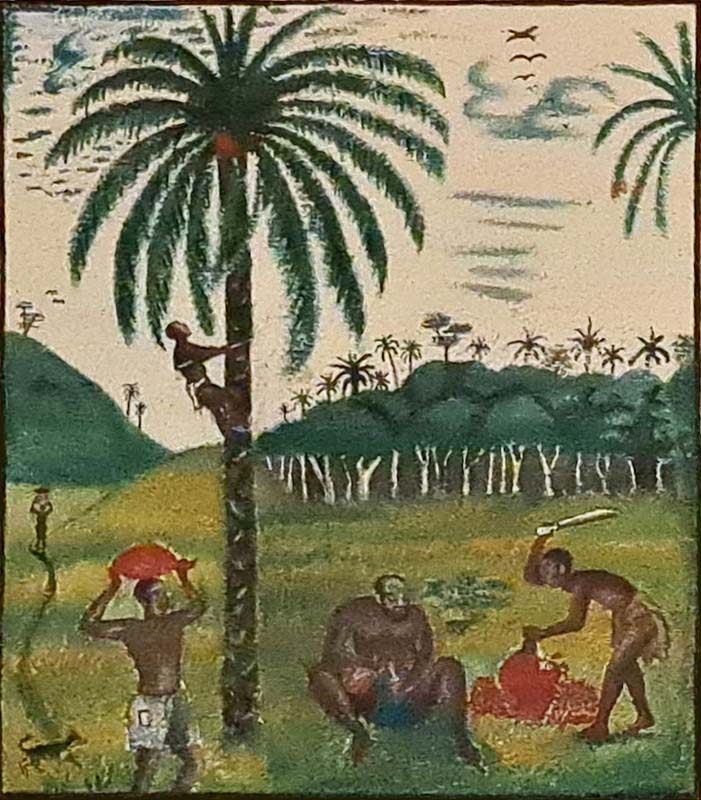

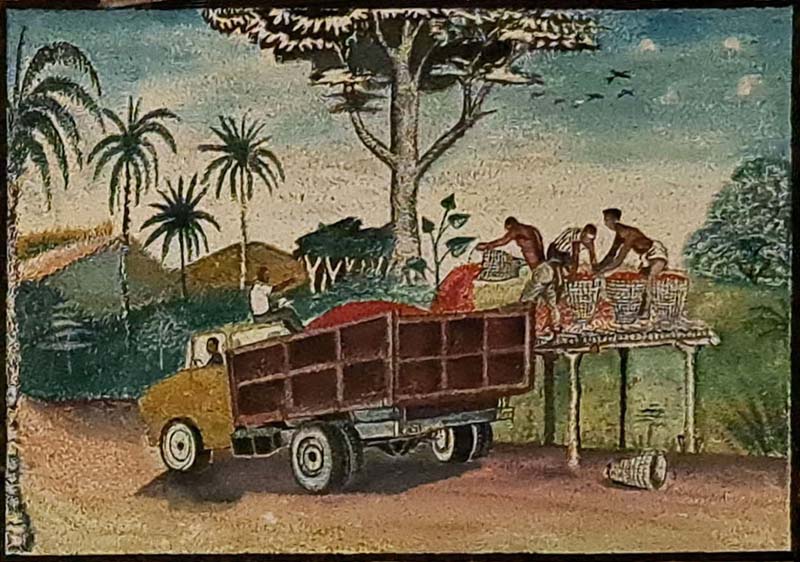

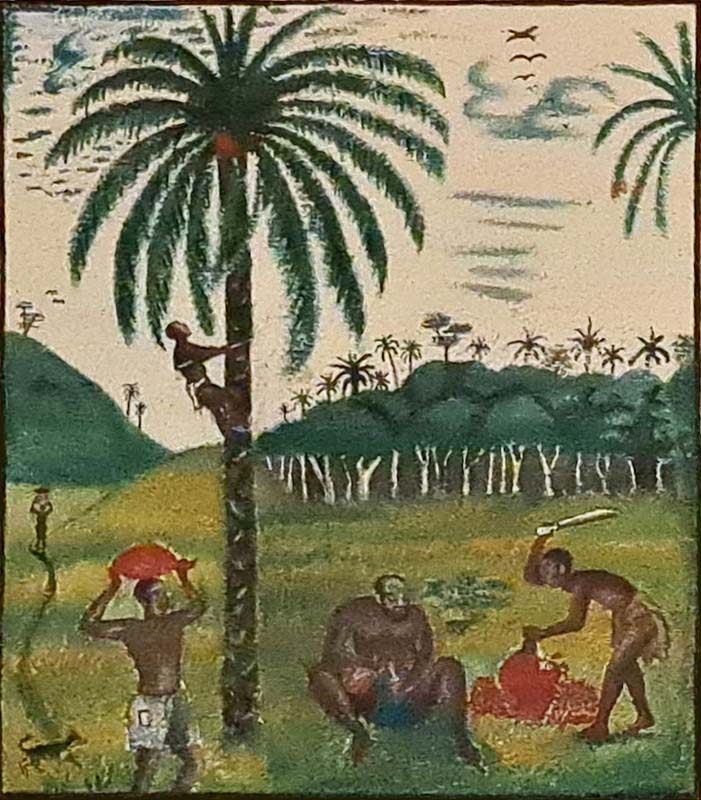

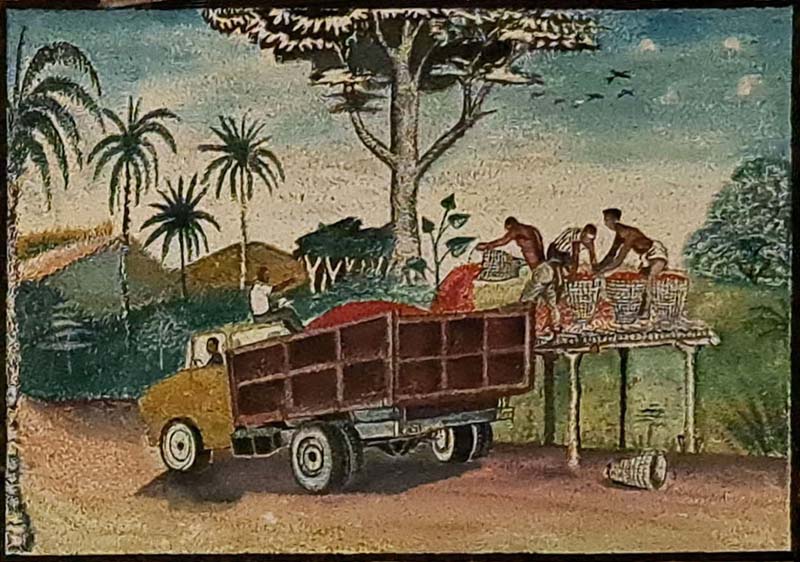

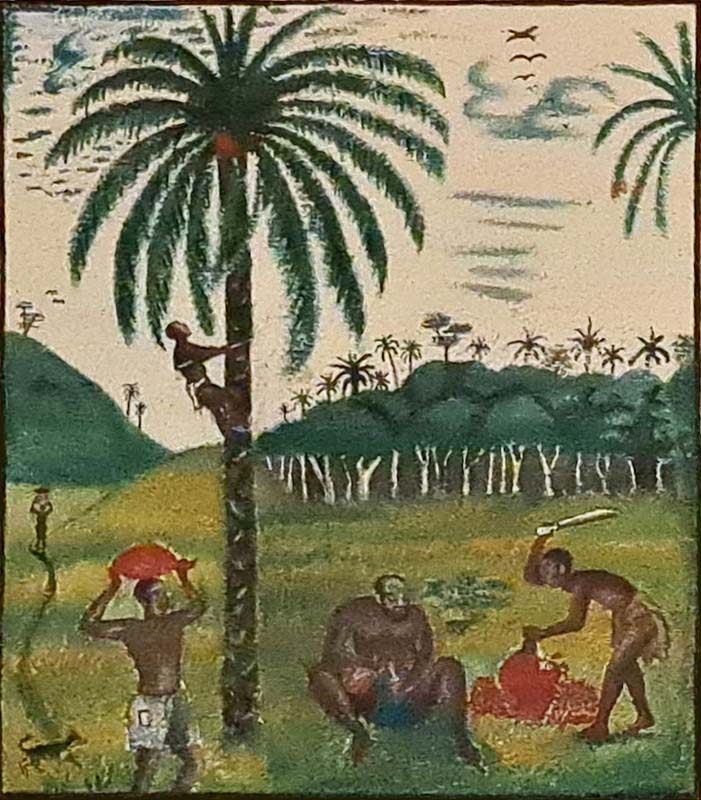

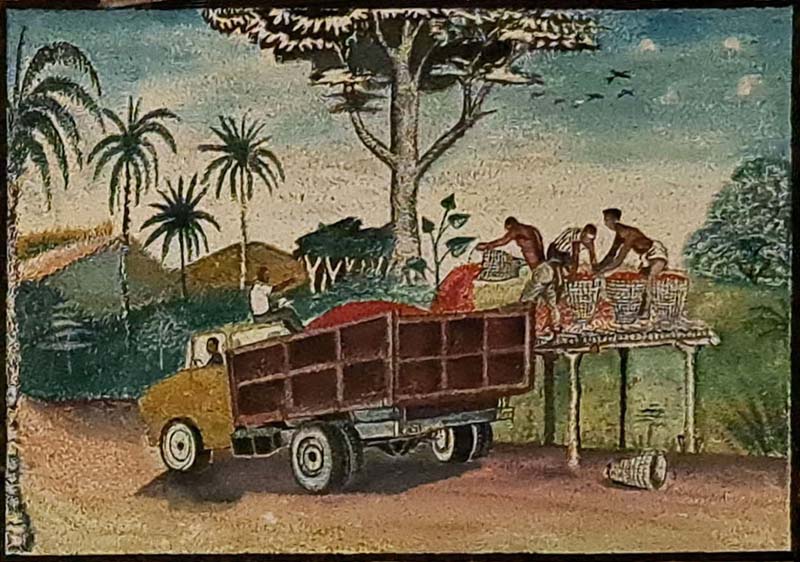

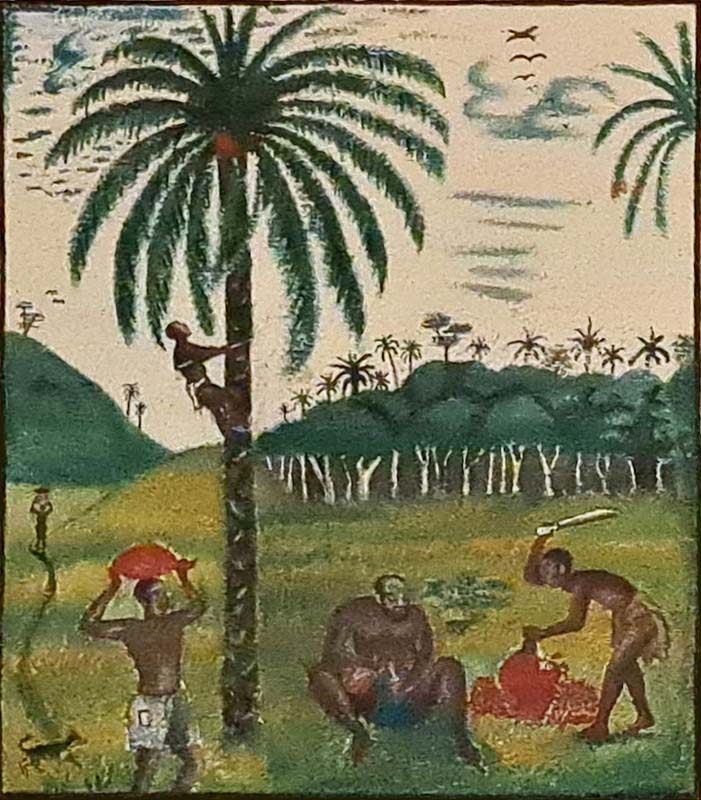

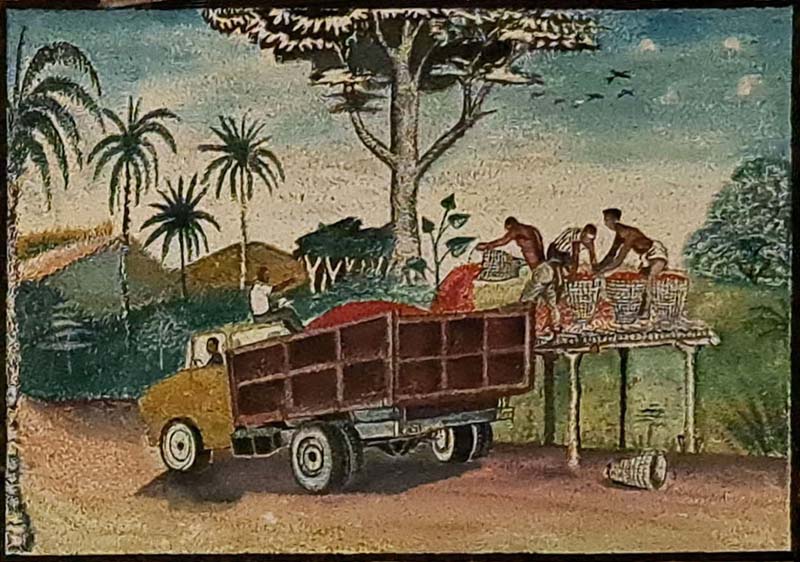

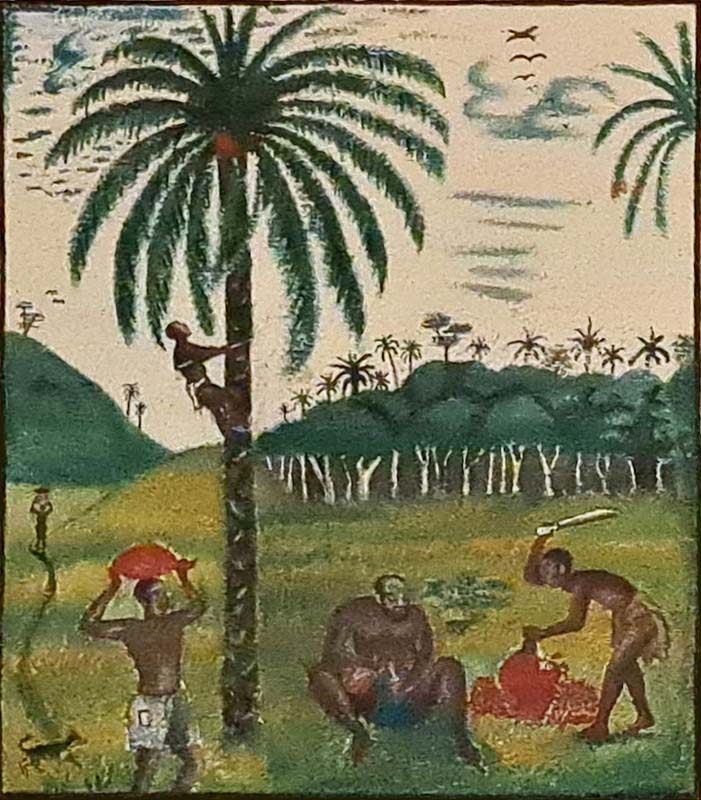

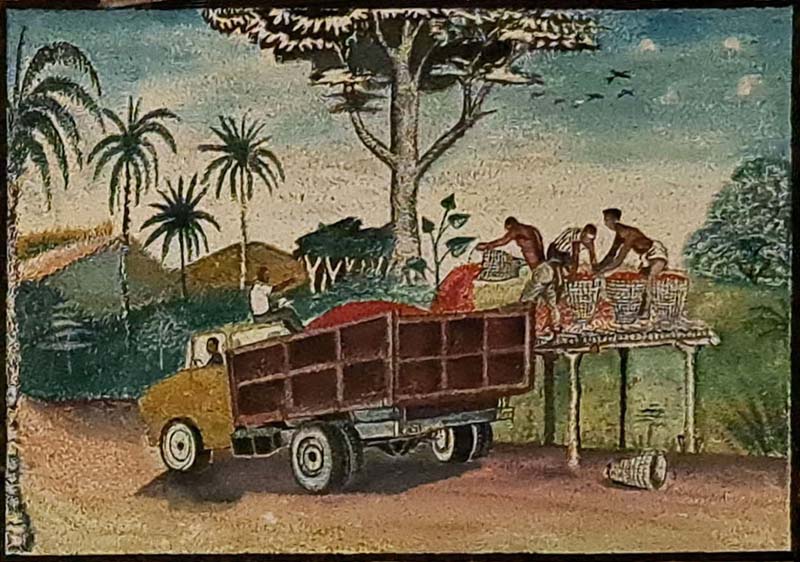

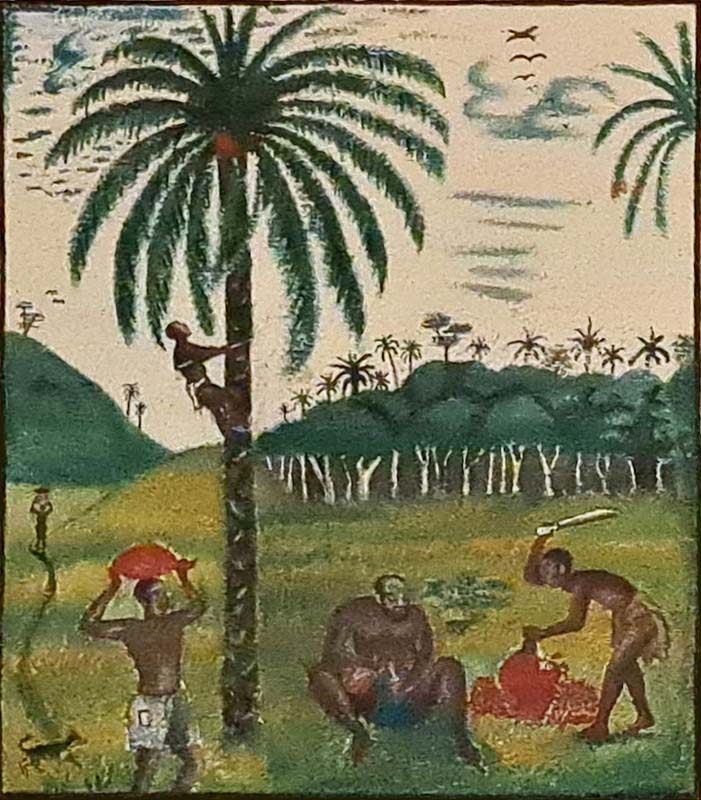

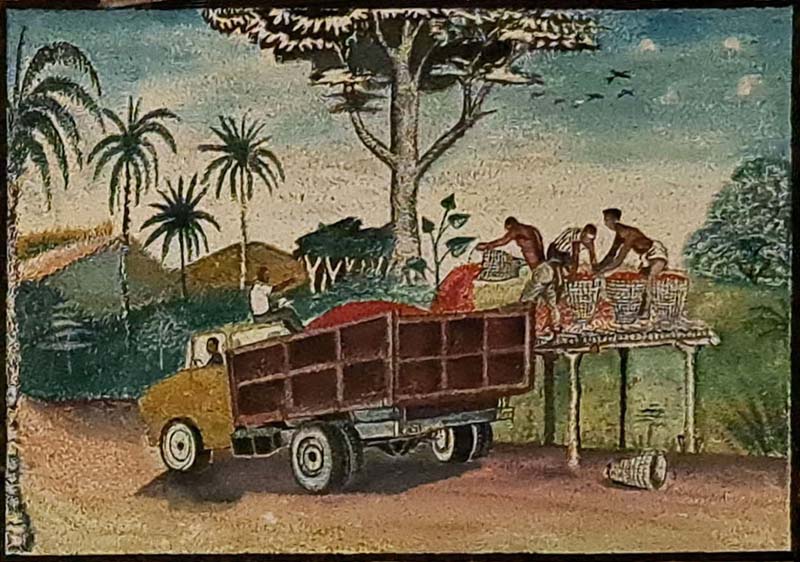

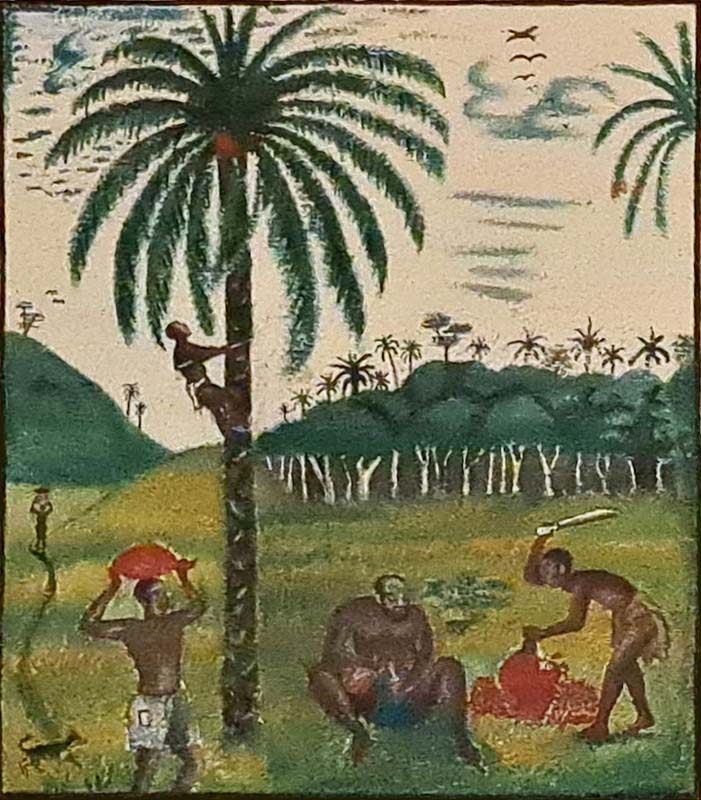

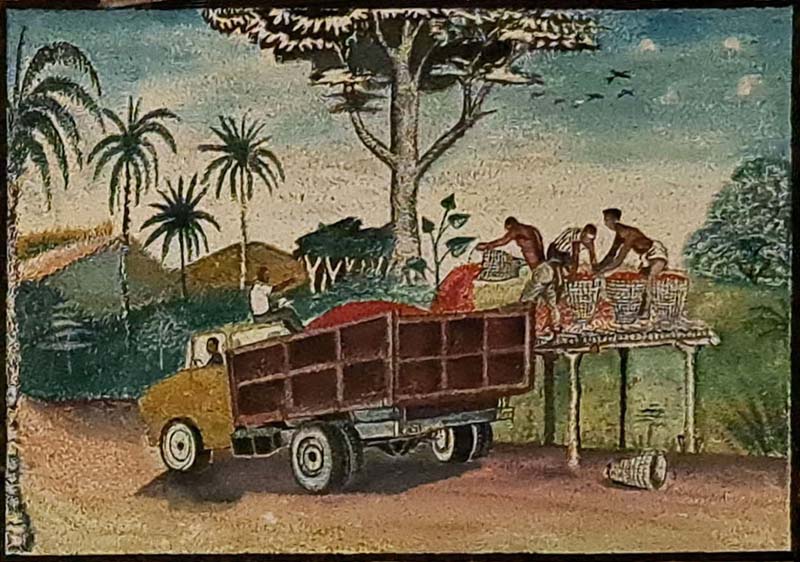

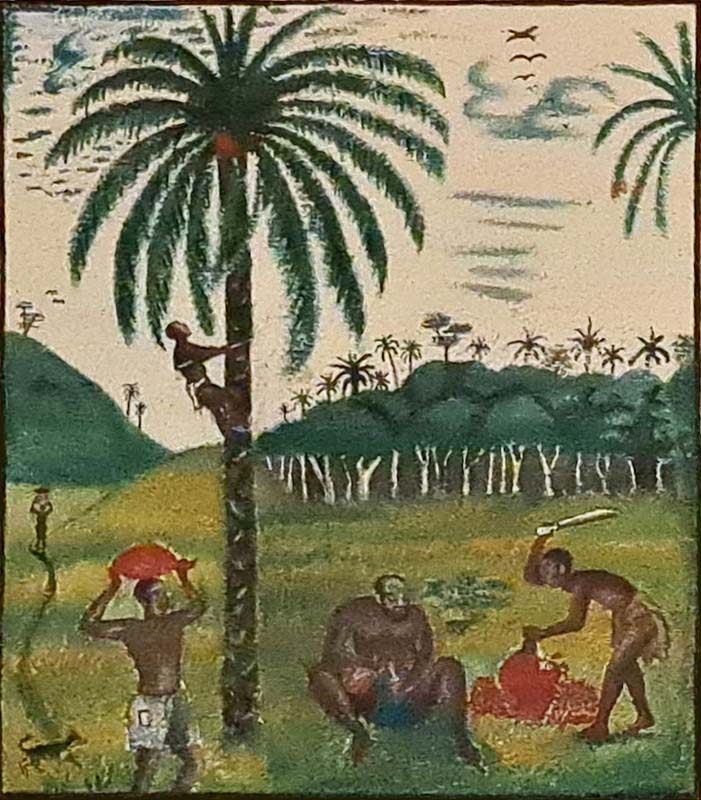

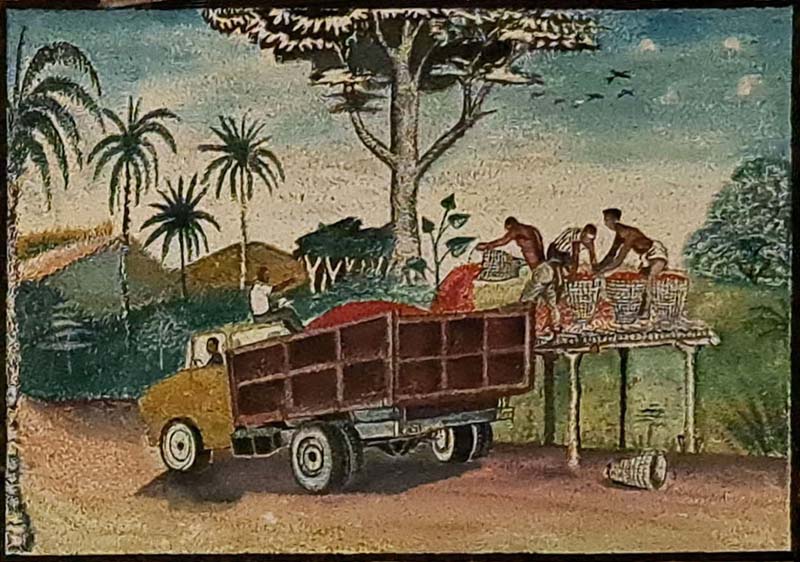

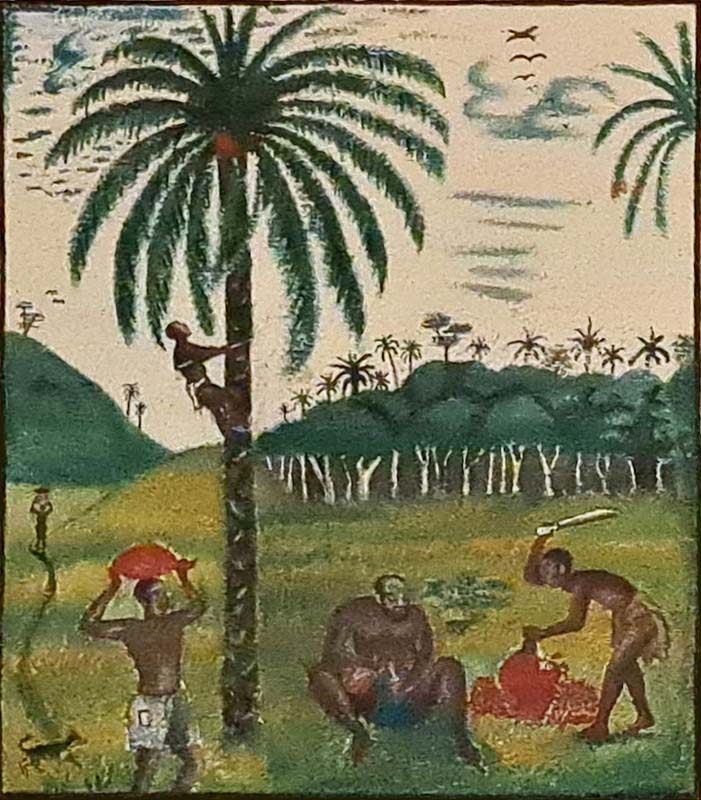

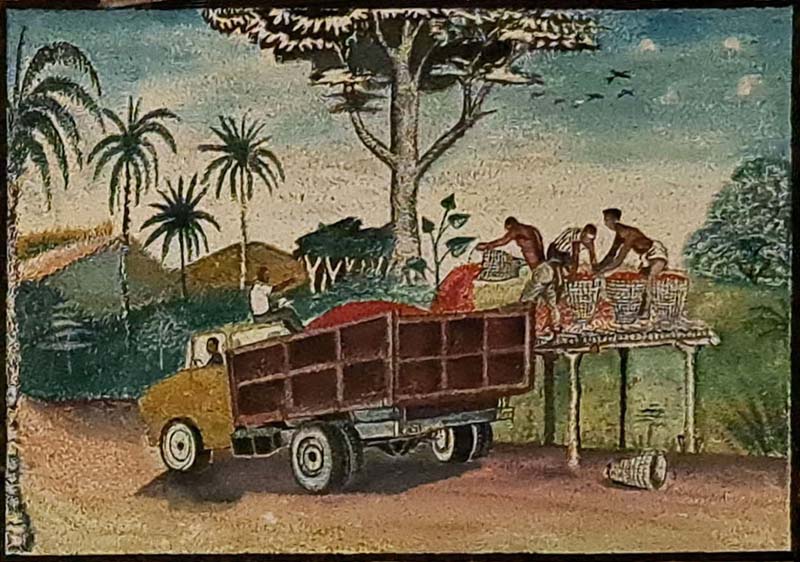

Mural paintings representing palm oil gathering and transport. The paintings are inside the Cercle Elaeïs, the private club of senior Unilever workers in Lusanga. Benoit Henriet dates the murals in the building to 1989 and attributes them to Sissi Kalo.

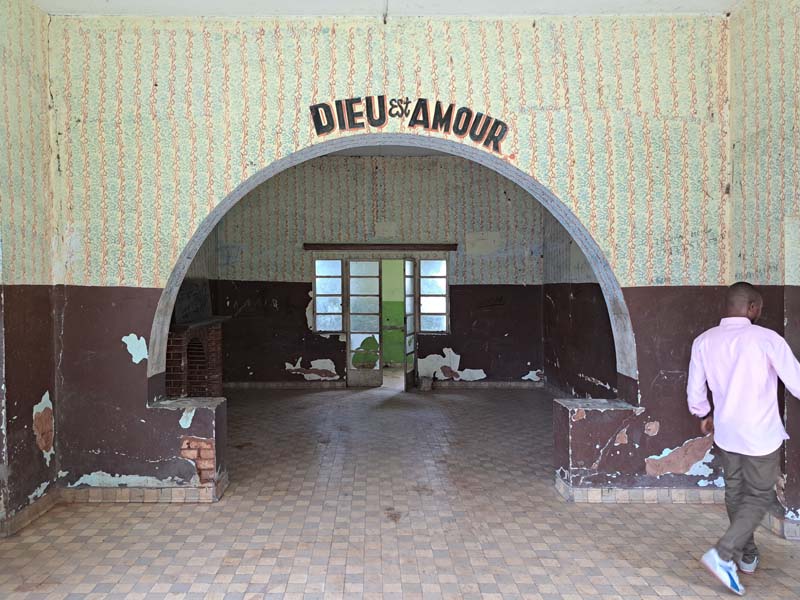

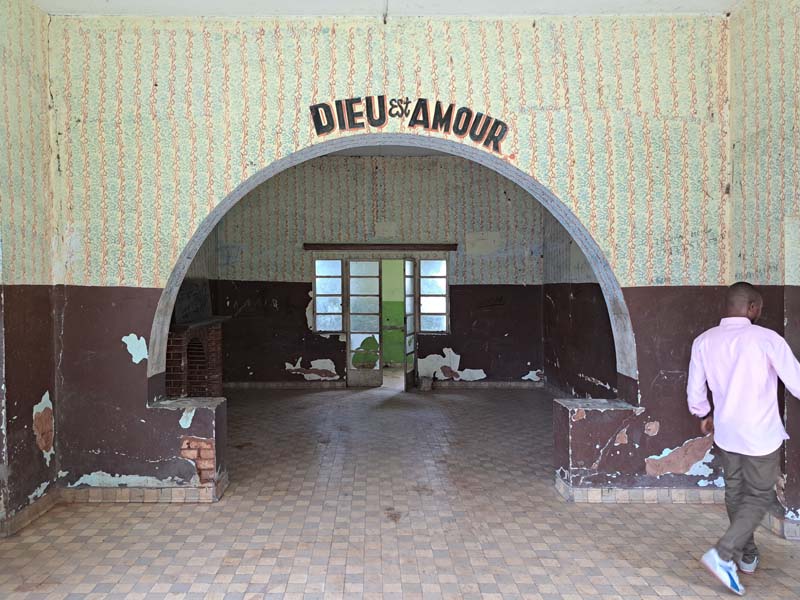

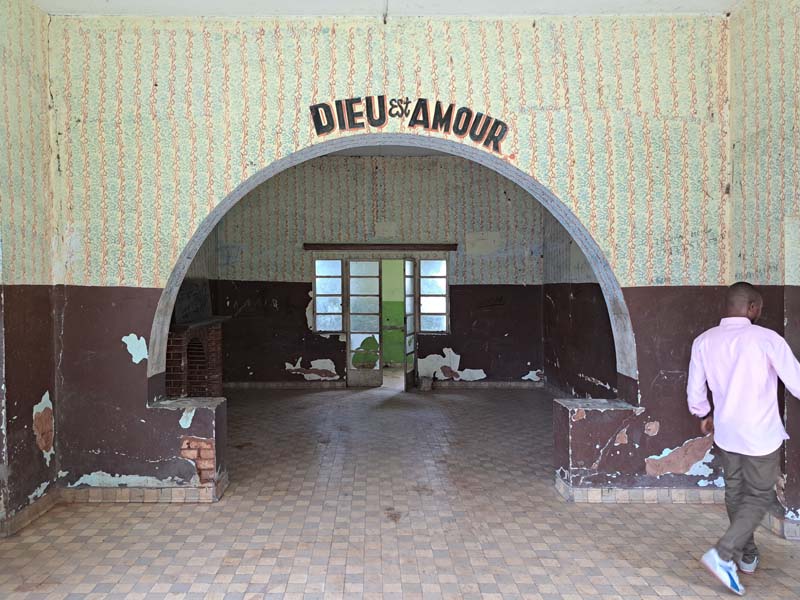

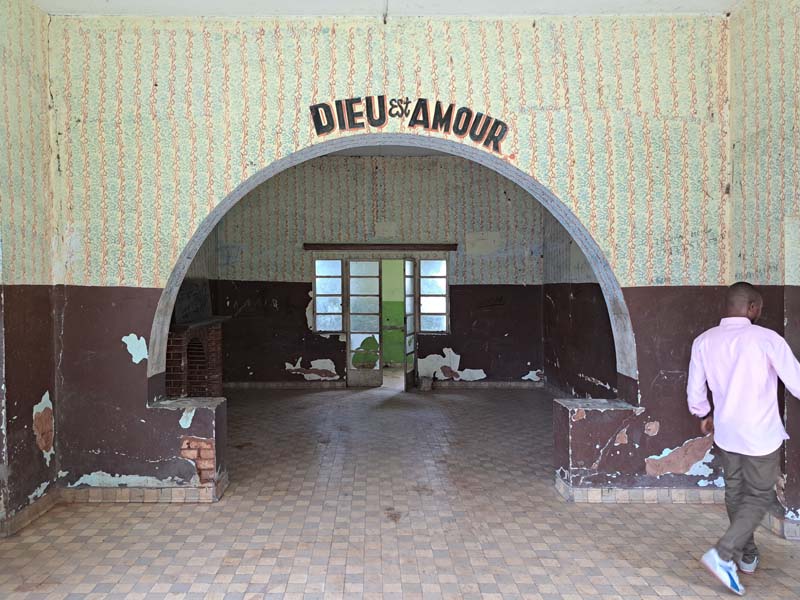

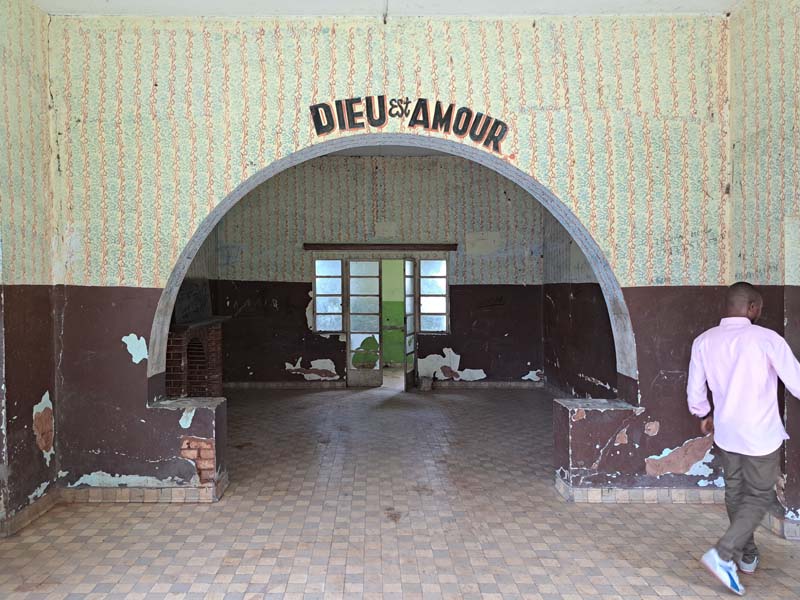

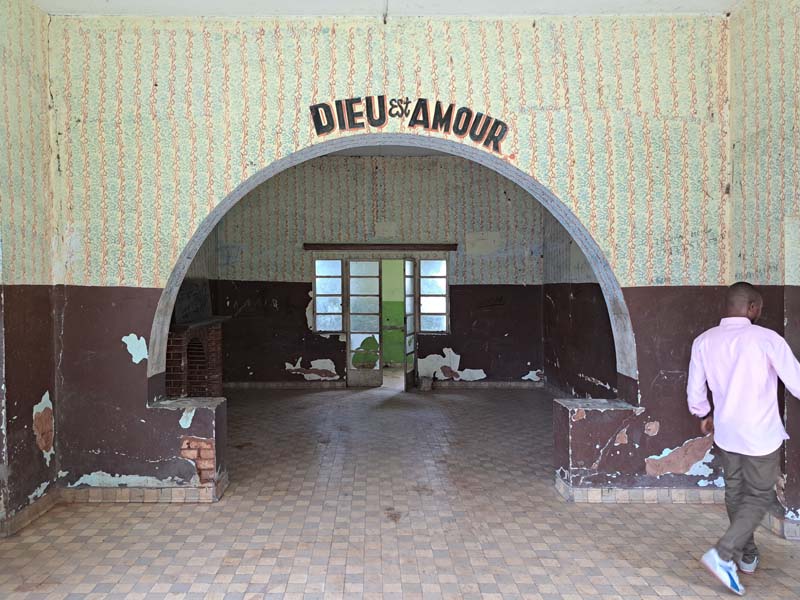

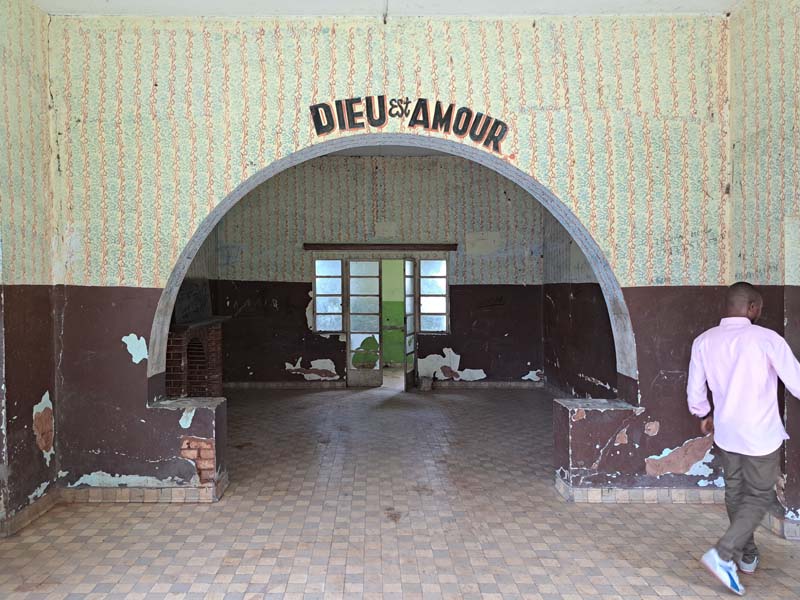

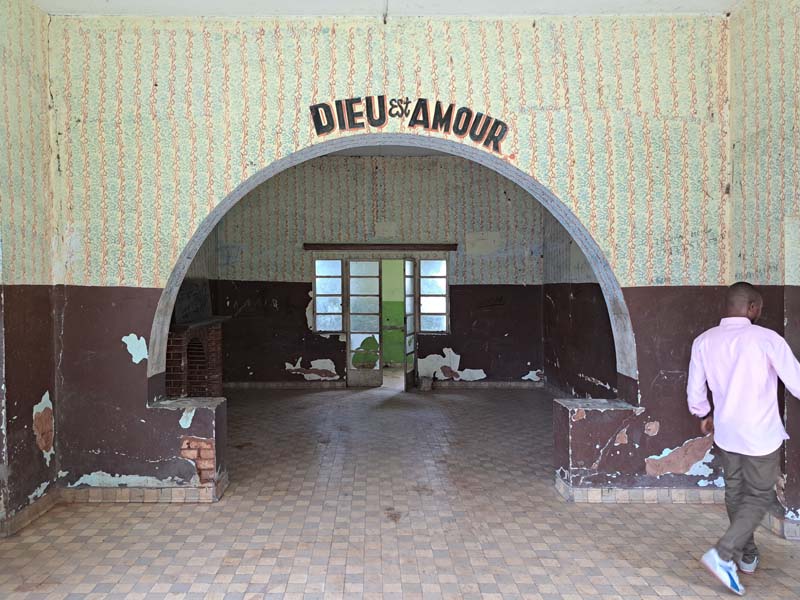

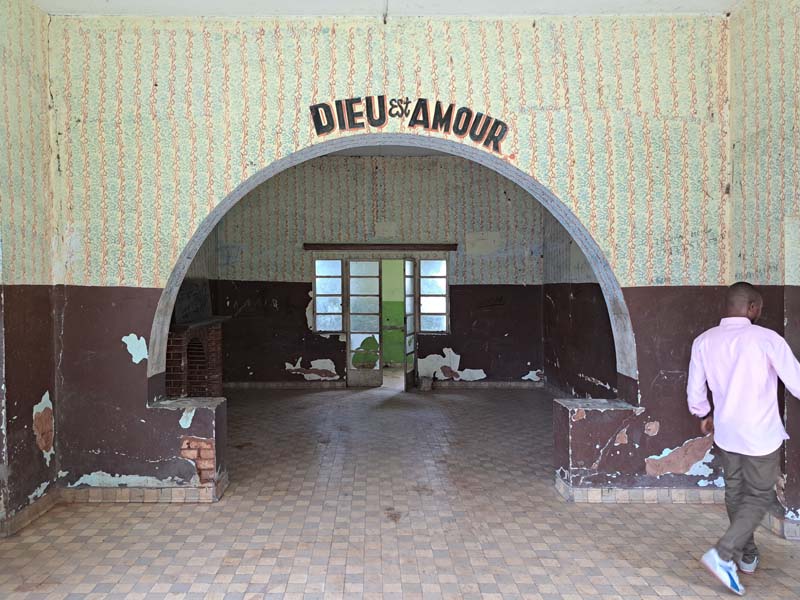

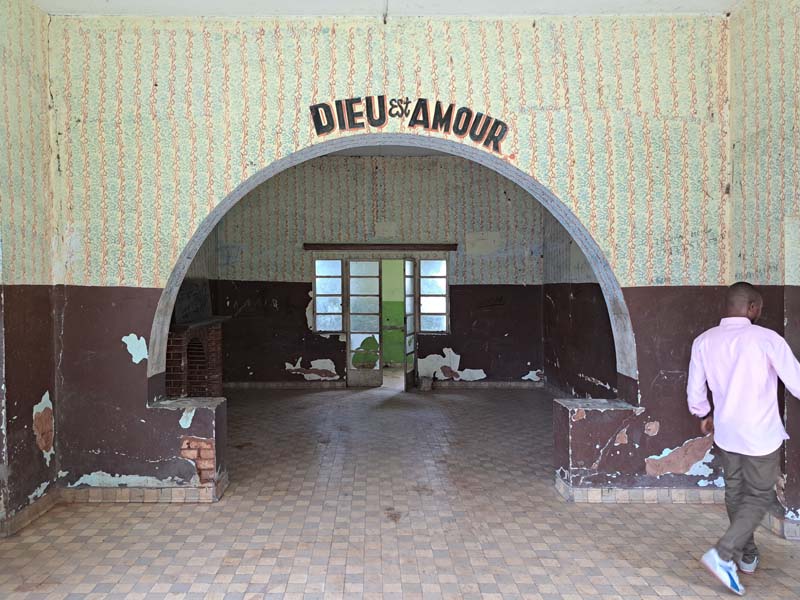

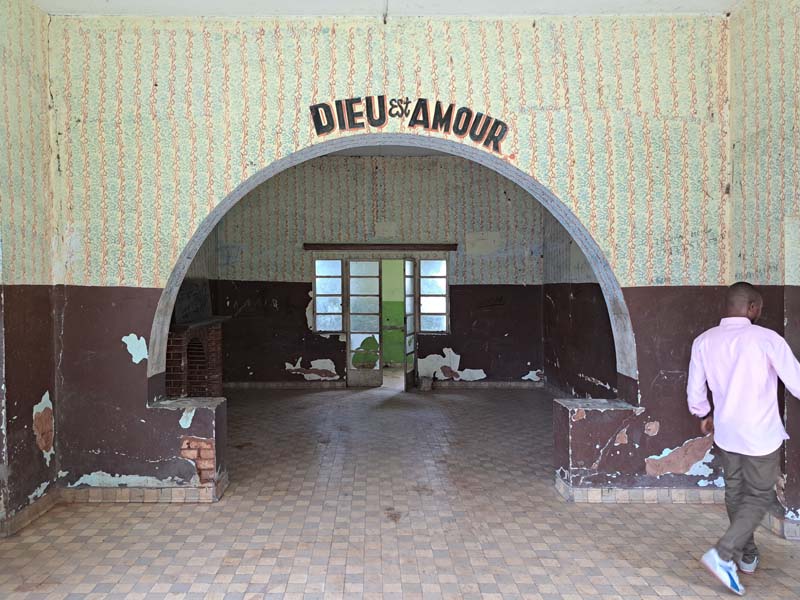

The Church of the Catholic Mission in Banga Banga, Lusanga. The mission was originally funded by HCB and managed the schools built in proximity to the palm oil mills, as established in the Convention between HCB and the Belgian colonial government.

When I visit Lusanga for the first time, my experience cannot help but be influenced by the accounts of historians such as Jules Marchal [v] and Benoit Henriet [vi], who detailed the brutality of Lever Brother’s exploitation, especially in the Belgian Congo, the forced resettlement of the local population, and the violent repression of “uncooperative workers.”

I am staying in one of the missions originally funded by Huileries du Congo Belge, and one of the local directors of the new company that now owns the site, after Unilever definitively abandoned it in the 1990s, is accompanying me on the visit. In fact, a visit would not have been possible without his permission and guidance. The company, indeed, far from being simply an actor among others active in the area, and similarly to the previous Anglo-Belgian ownership. was perceived by everyone in the village—from the inhabitants and the local authorities with whom I could talk, to the missionaries who hosted me in their foyer—as essentially the ‘owner of the place’.

The company owned not only the forest land, the plantations, the administrative buildings, and the warehouses located next to what were once the main river docks of Lusanga at the confluence between the Kwilu and Kwenge rivers. It also owned the rows of villas aligned along the riverbanks, the ten or twenty halls and dormitories and buildings, some of them now completely abandoned of what is still called l’hopital Européen – the hospital for the Europeans – and the hundreds of houses, arranged in rows along series of parallel, large avenues built in various phases to host the plantation workers.

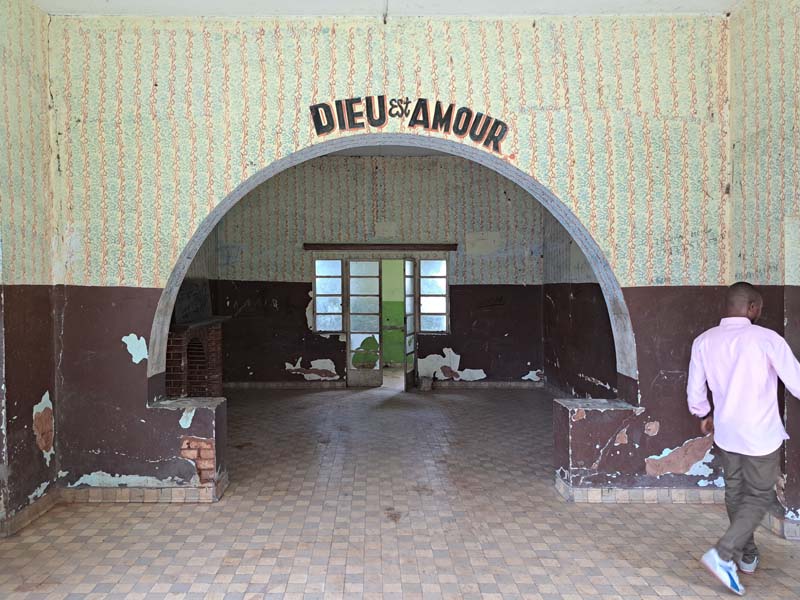

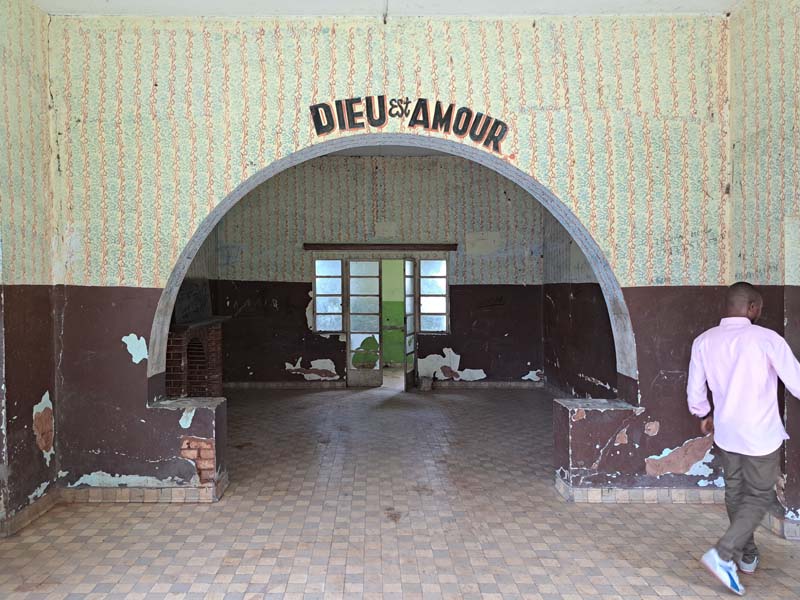

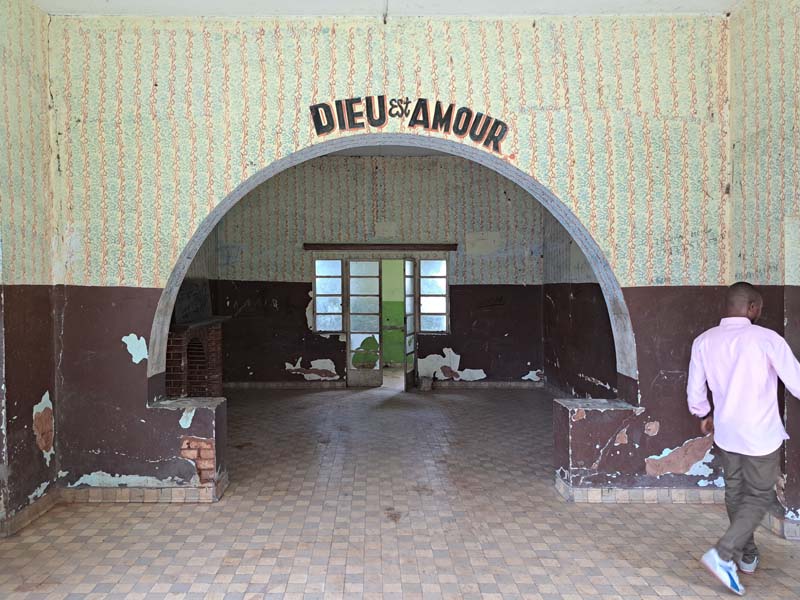

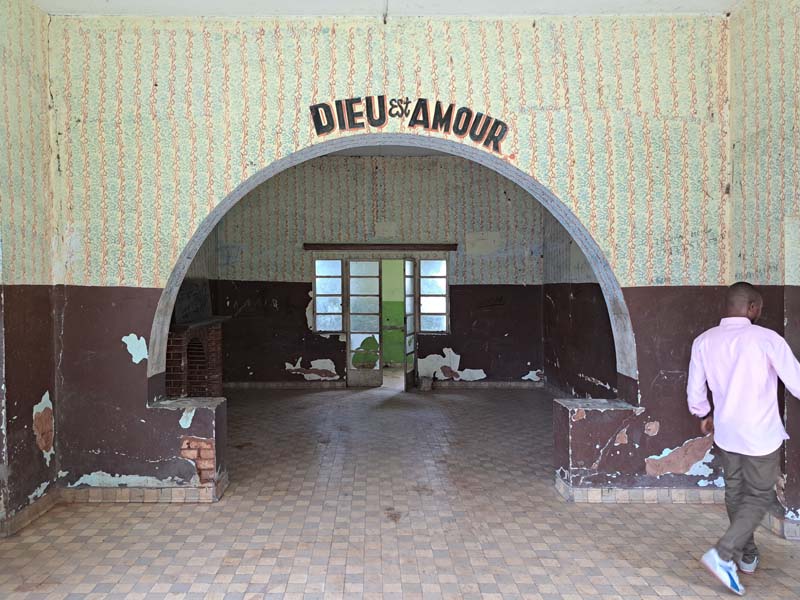

Exterior and interior views of the now derelict Hopital Européen built in the 1950s.

My guide lived in one of the villas for the European managers. Despite the company employs nowadays only Congolese managers and workers, the social and functional segregation in Lusanga seems to accurately retrace that of its first establishment, a century before. The company managers occupied the spaces conceived for the colonizers and the workers’ houses separated by a cordon sanitaire. Except for the fact that nowadays there are no Belgian, Dutch, British or Italian managers, and the racial segregation has been substituted by class segregation.

A worker's house in Lusanga. This residential typology hosted a specific category of Congolese skilled workers who, having received some formal education, were called, in colonial jargon, "évolué," literally meaning 'evolved.' The expression is still widely used in the DRC.

House originally intended for the European functionaries. Lusanga.

Yangambi

The continuation of my journey takes me to the opposite side of the DRC, to Yangambi, along the Congo River, home to the largest agronomic research center in the country, the Institut National pour l'Étude Agronomique du Congo Belge (INERA). Following the course of the river downstream from Kisangani, one can understand why, in 1933, it was decided to establish what was then called the Institut National pour l'Étude Agronomique du Congo Belge in this location. After two or three hours of fast navigation along nearly flat banks, the river, crossed lengthwise by oblong islets, resembles a lake even more as the expanse of water widens. And the banks become steep, offering a terrace rising several dozen meters above the river level, on which the first rows of Yangambi's buildings scenically overlook.

The INERA is a vast complex of facilities, research laboratories, training centers, specialized libraries, and herbaria, but also trial gardens, and experimental plantations that make it a sprawling complex, surrounded by an extensive forest reserve. The palm oil sector of this research center is, or at least was, one of its crown jewels, as long as the colonial extractive economy financed its costs. It provided the seeds along with the training of specialized technicians for almost all the plantations in the country, including Lusanga.

Far from the traditional image of a university campus or research center, it is a site that spans nearly 25,000 hectares and includes, in addition to administrative and research buildings, a collection of scattered villas and residential quarters that accommodated the more than 10,000 people employed at its peak. During this time, the production and processing of palm oil, natural rubber, cocoa, and coffee for commercial purposes financed a thriving activity of selection and adaptation of plant species, which for decades were sent to establish the primary plant group for plantations located all over the world in tropical latitudes.

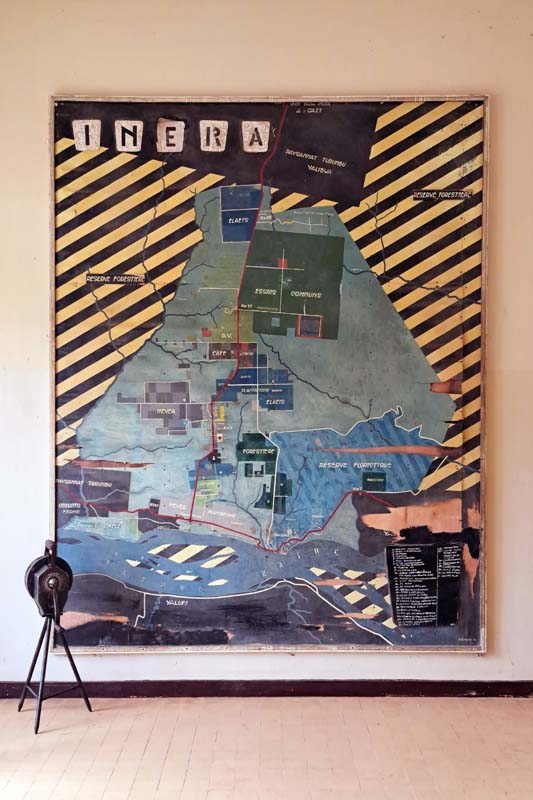

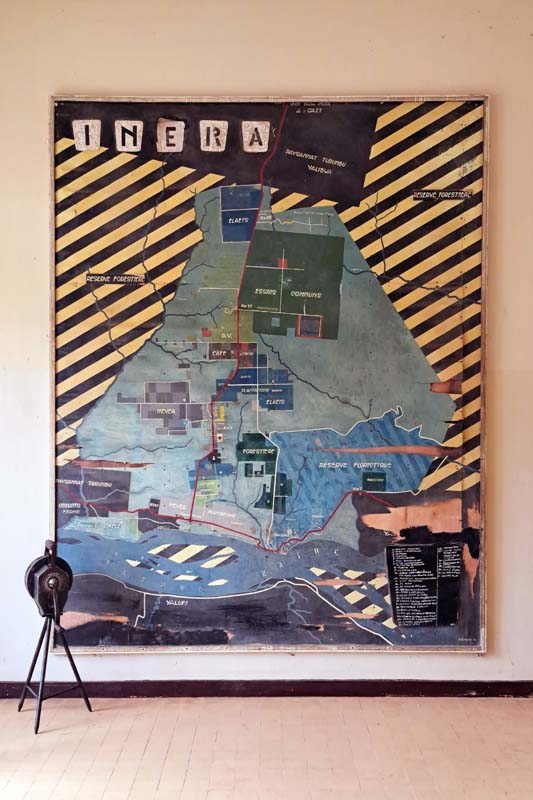

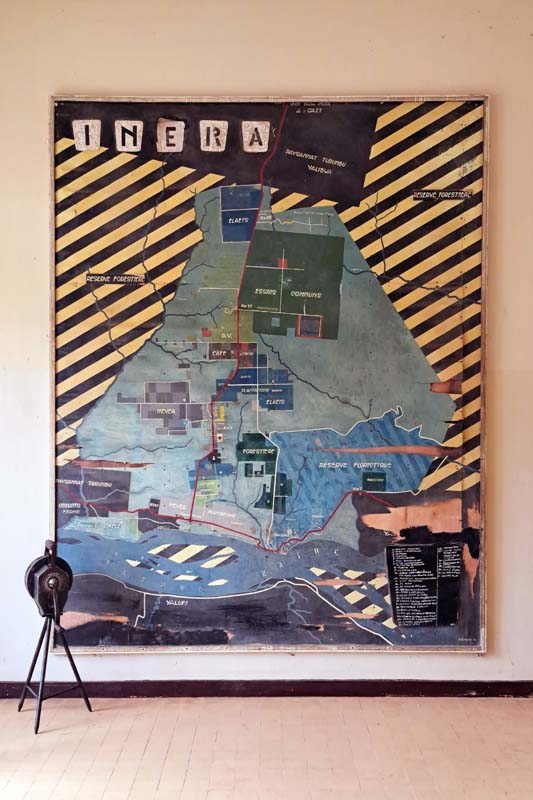

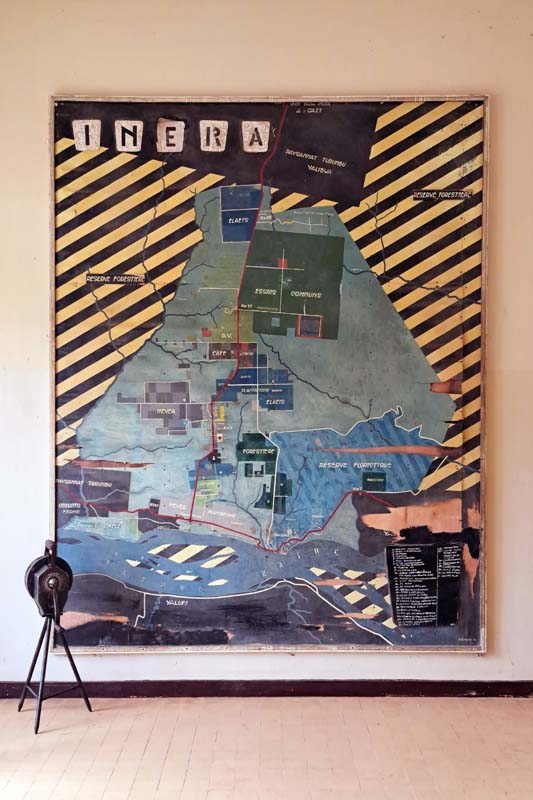

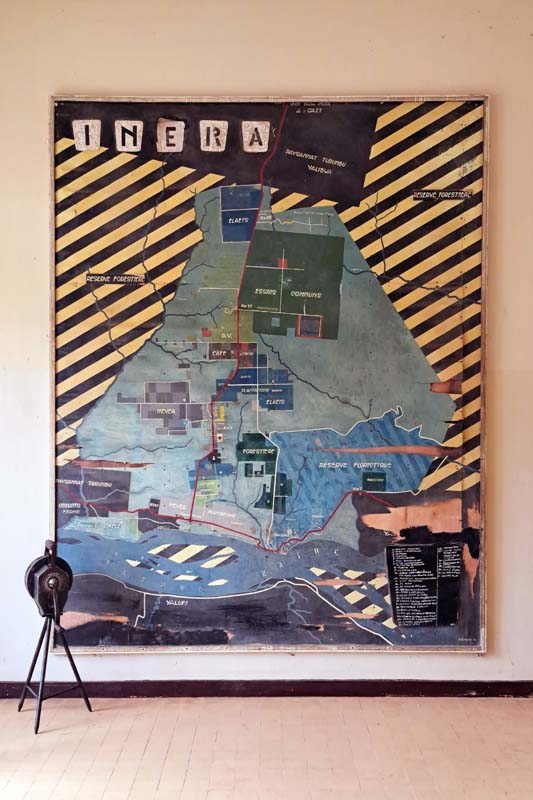

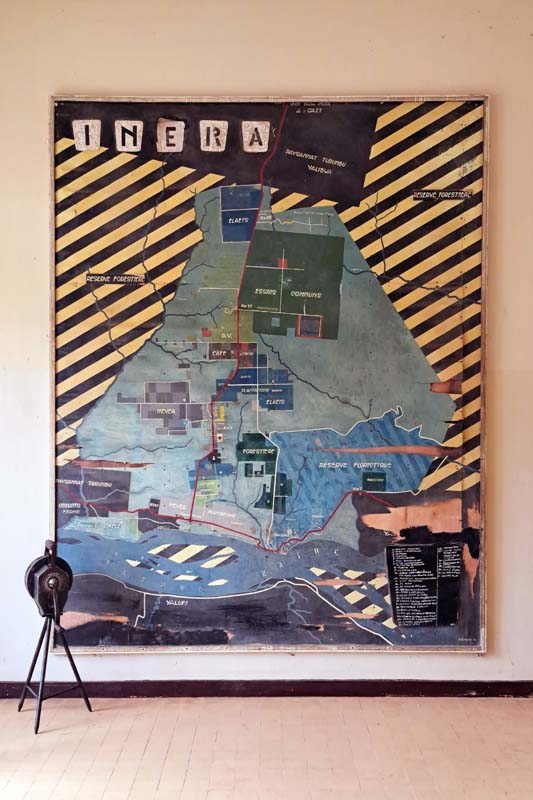

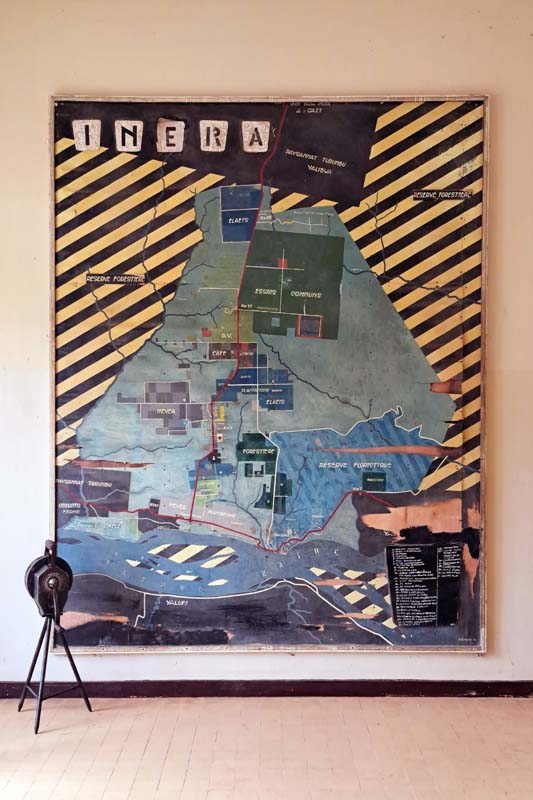

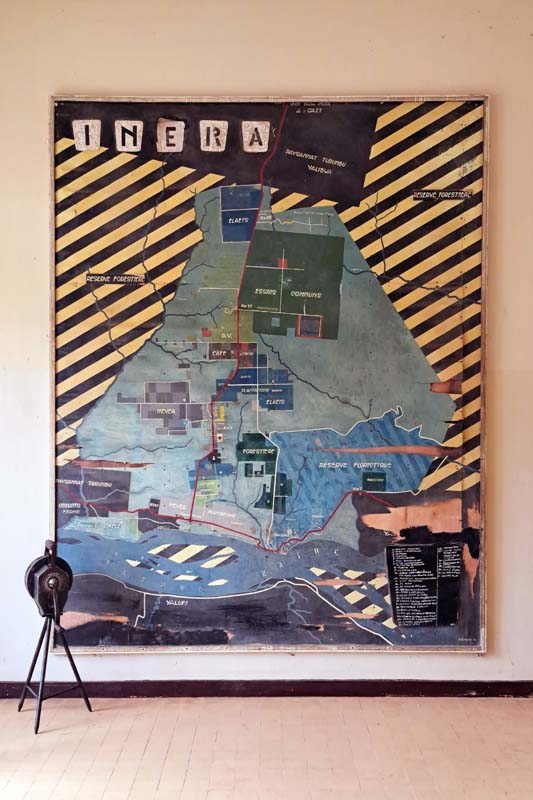

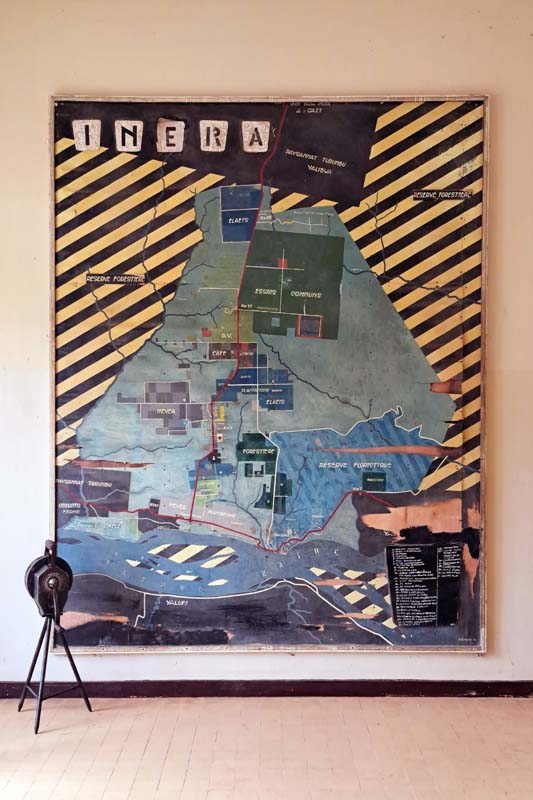

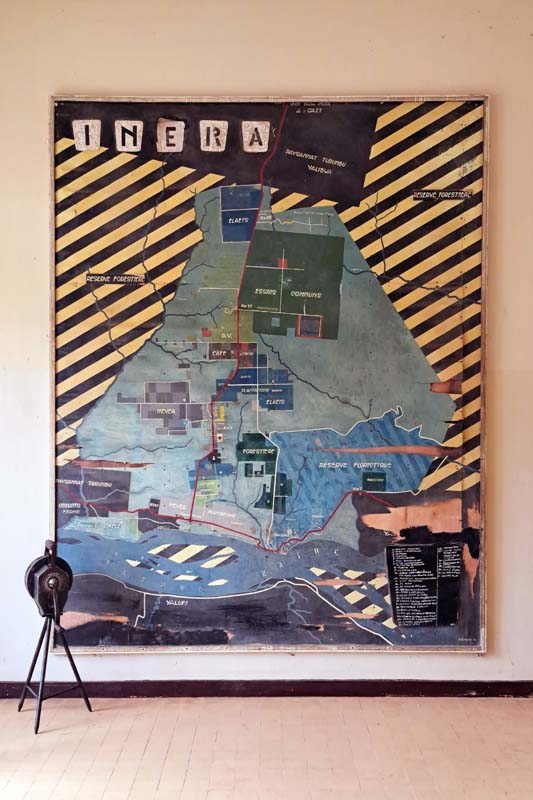

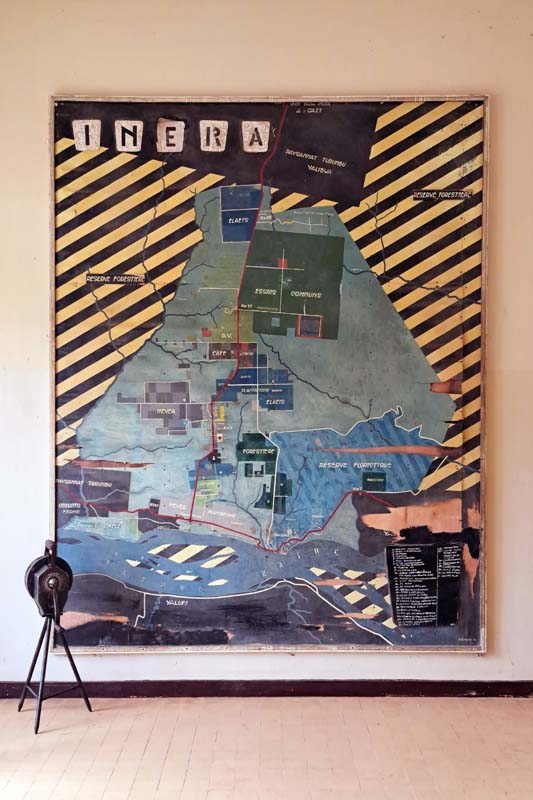

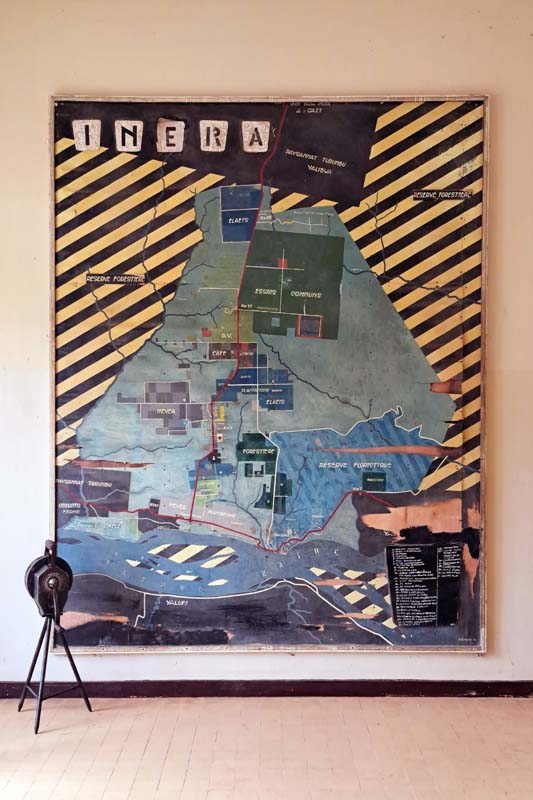

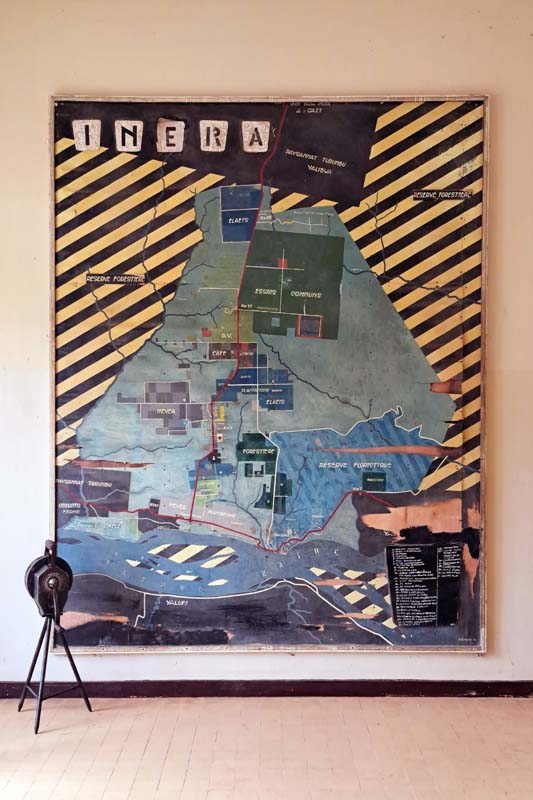

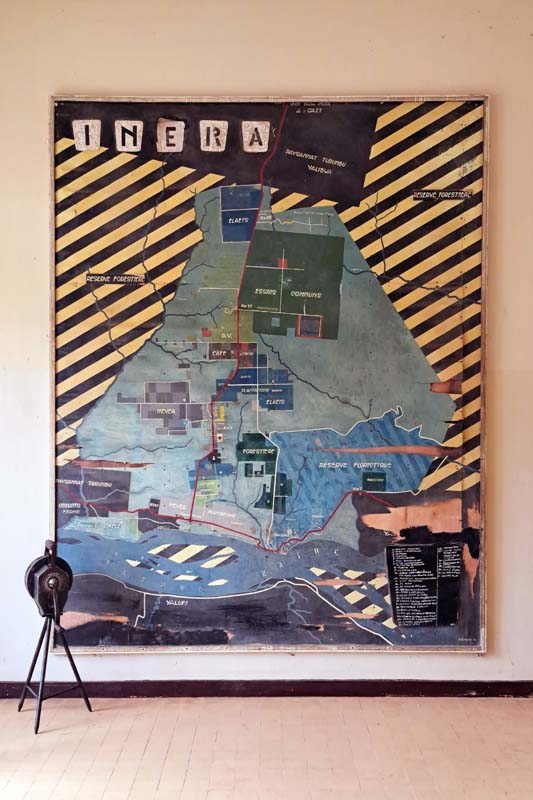

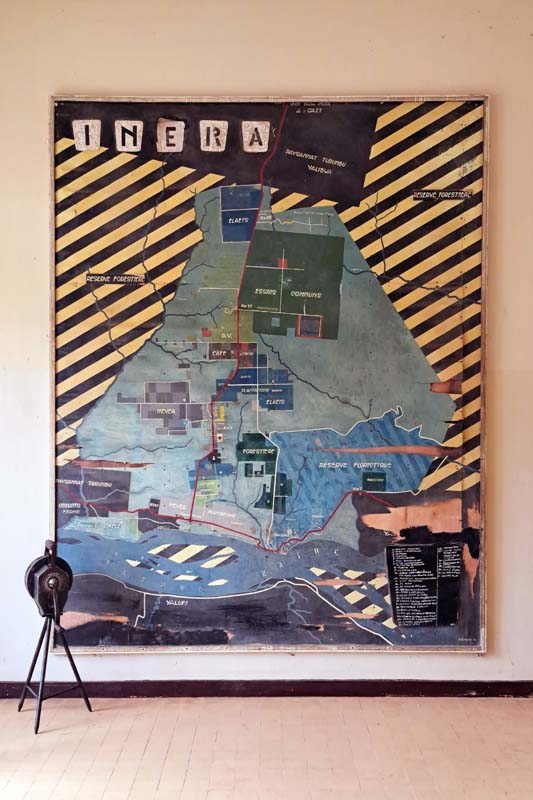

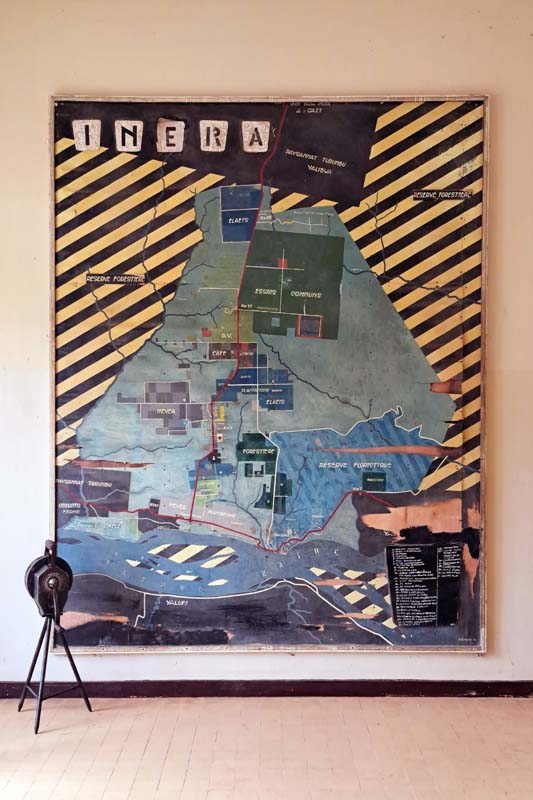

A large map (approximately 2 by 3 meters) of the INERA premises in Yangambi painted on a thin layer of wood. The map, dated 1954 and signed ‘Demolin’, is hung in the entry hall of the main administrative building of INERA, which also contains its library and archives.

The library's old cataloging system, arranged by topic.

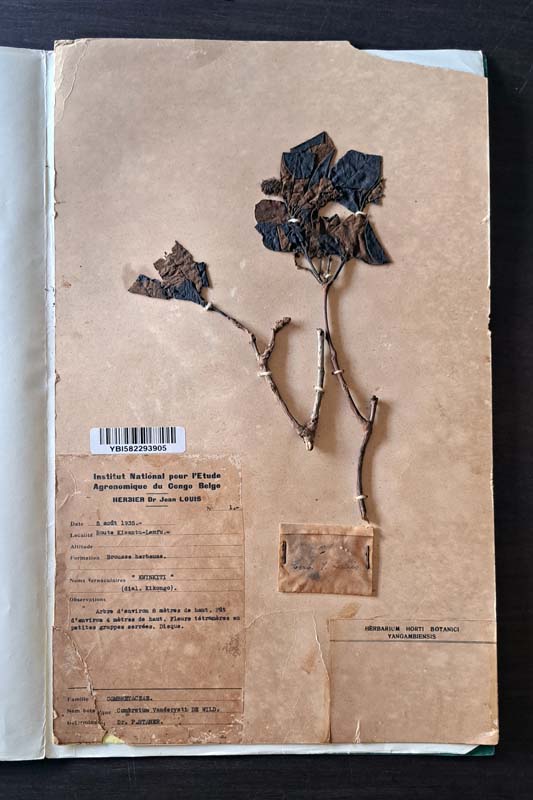

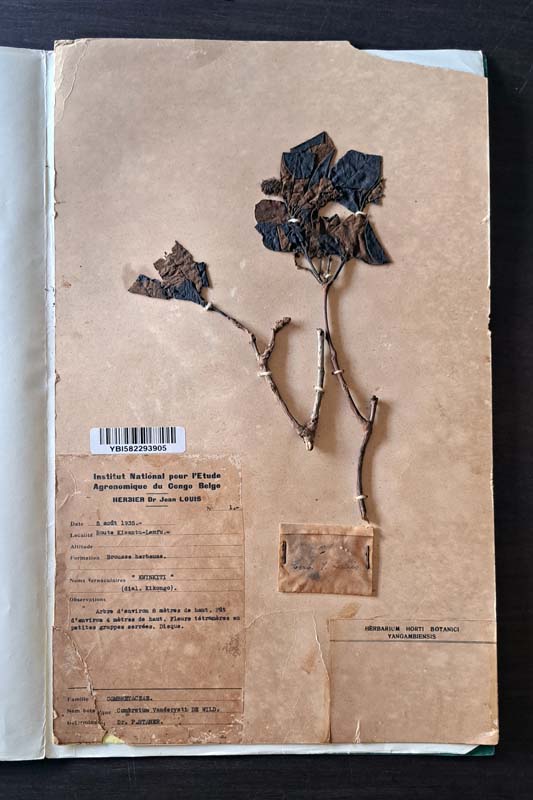

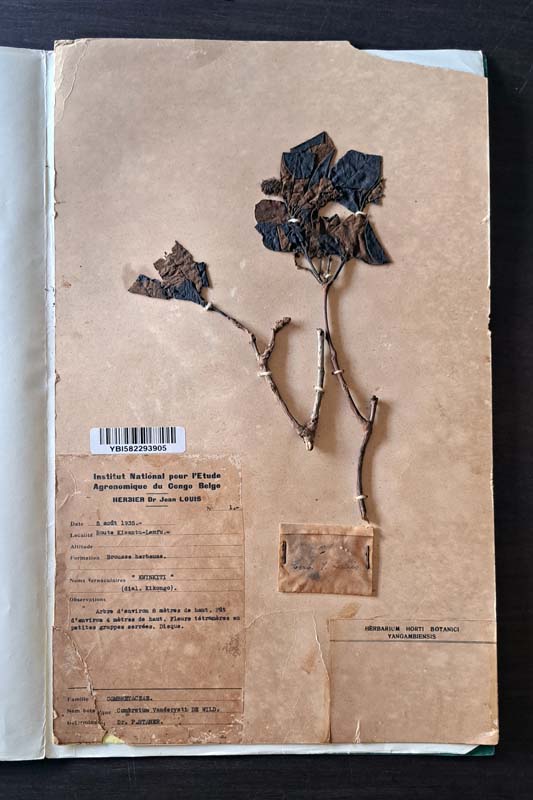

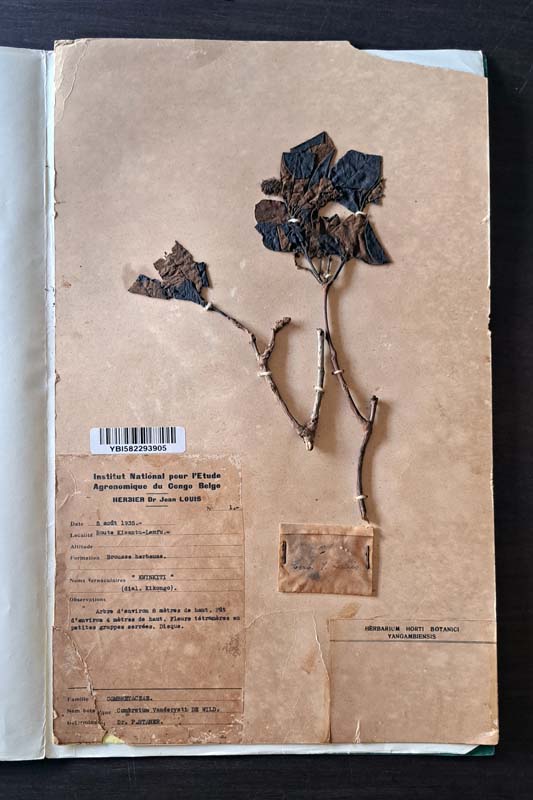

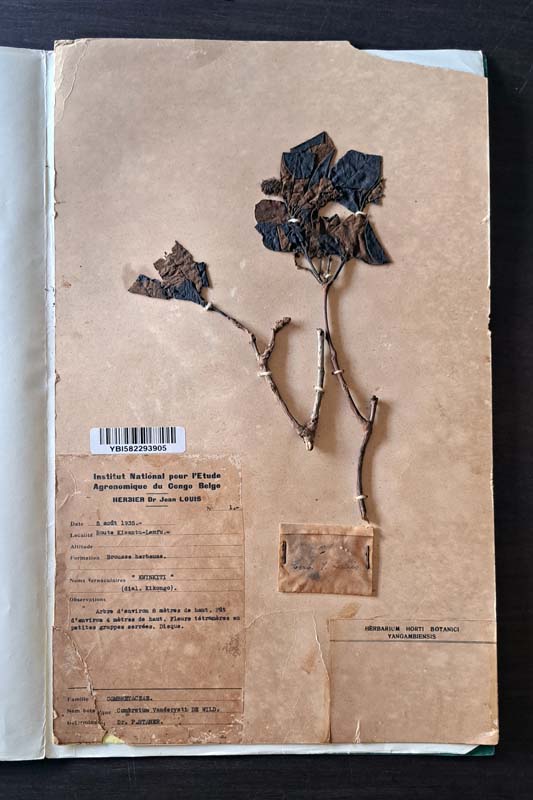

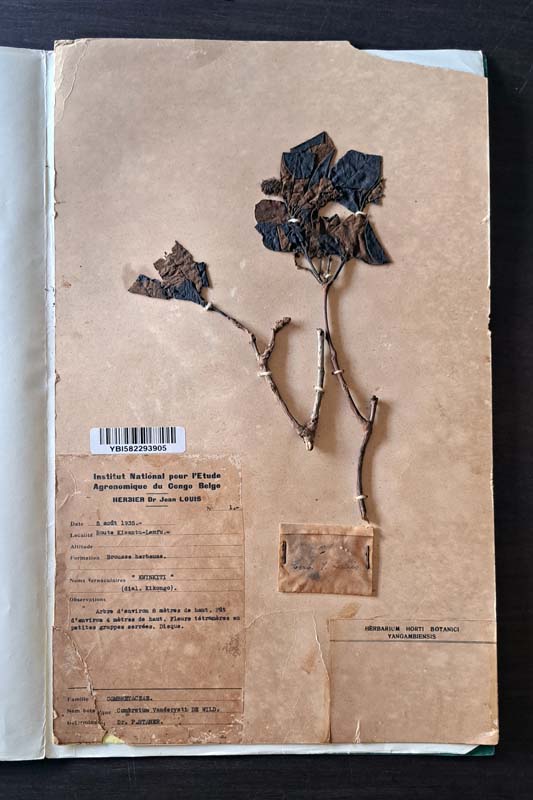

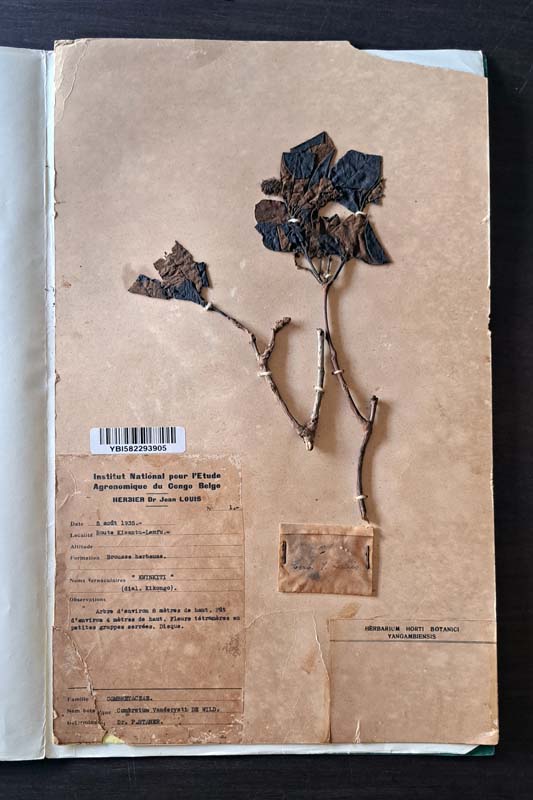

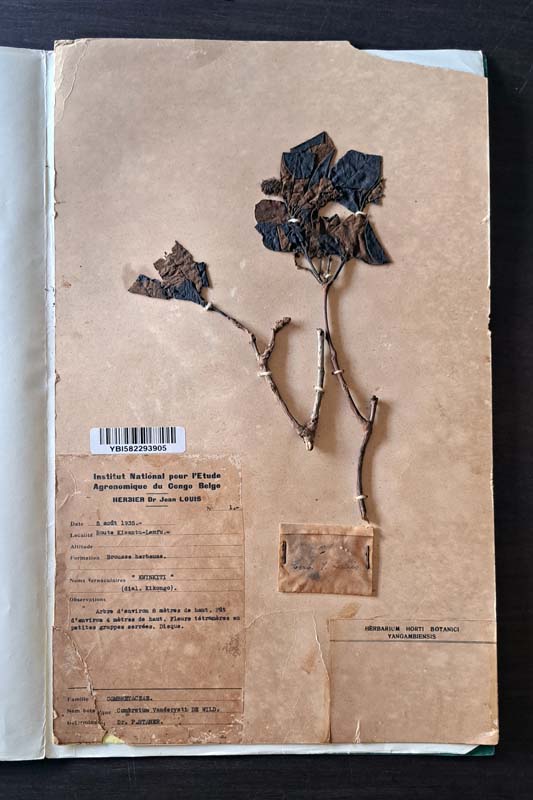

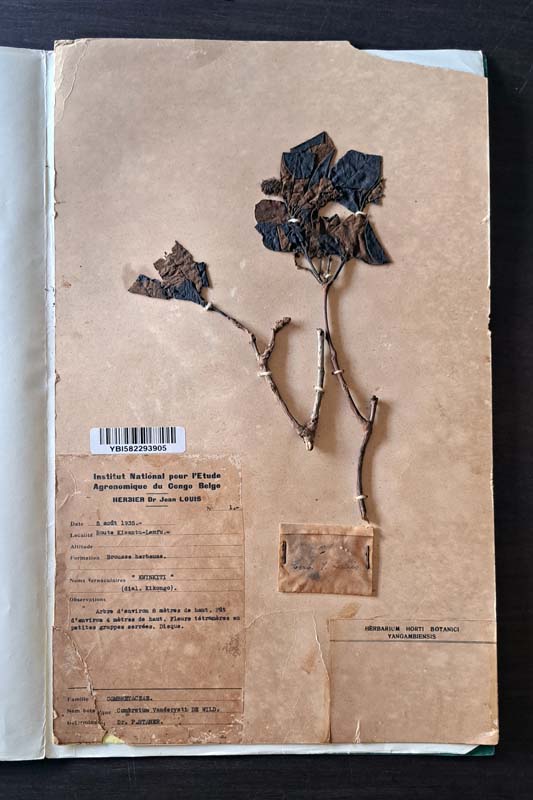

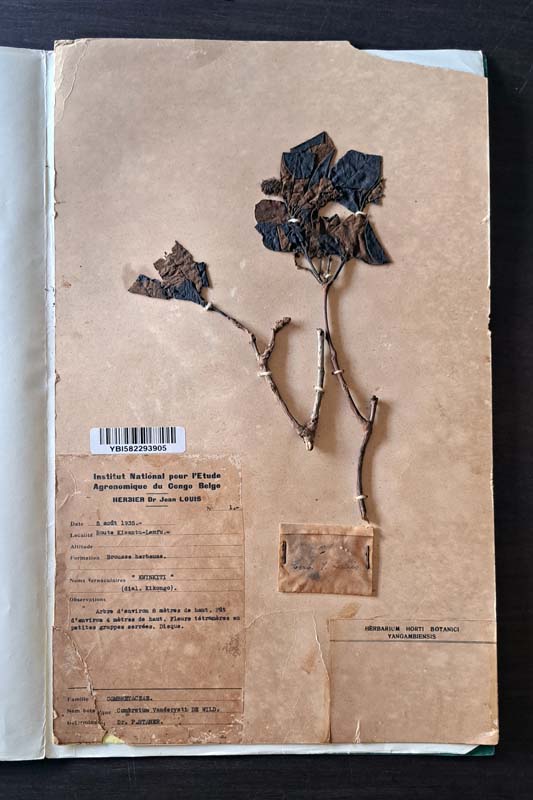

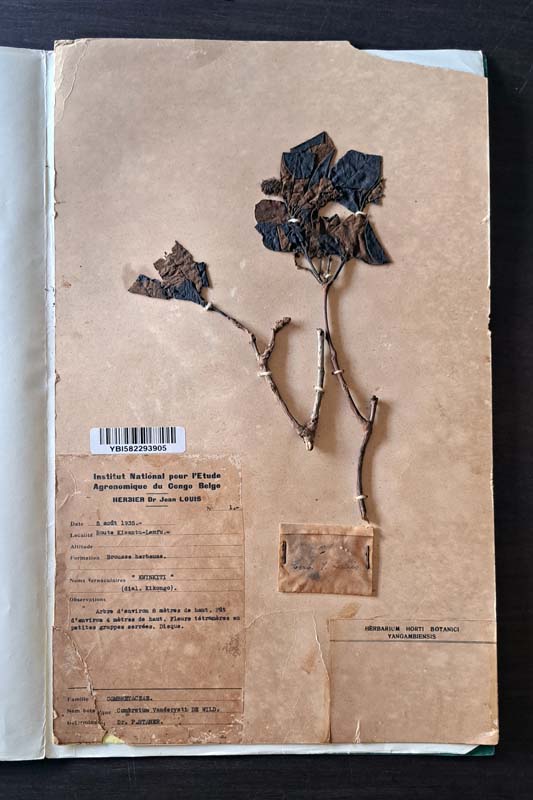

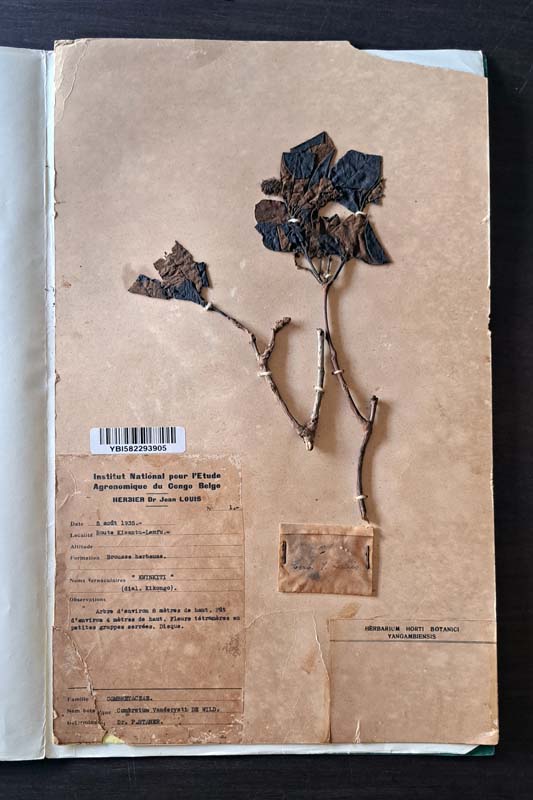

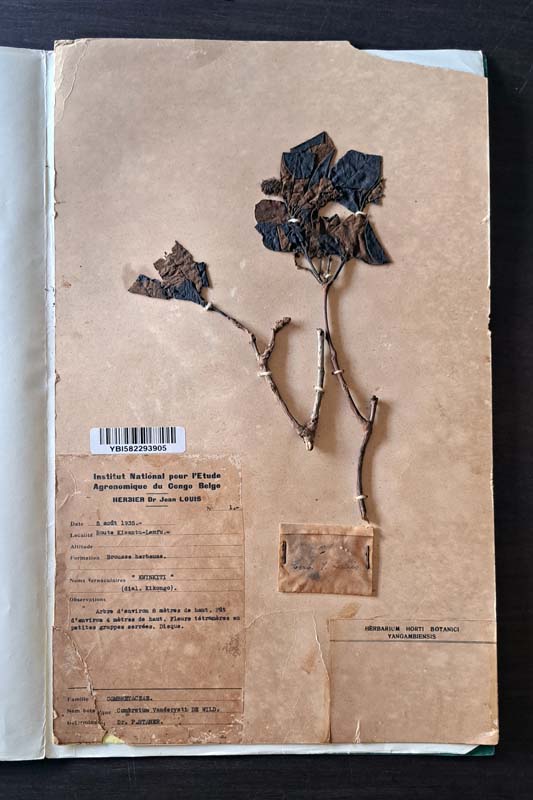

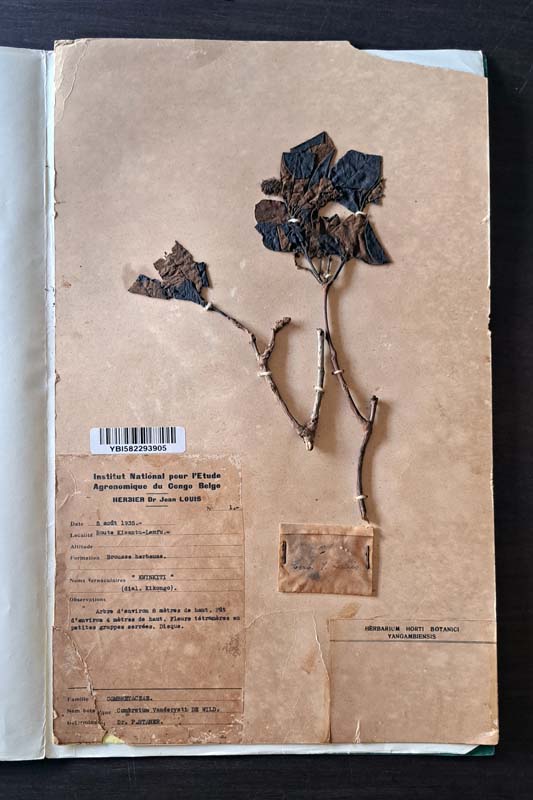

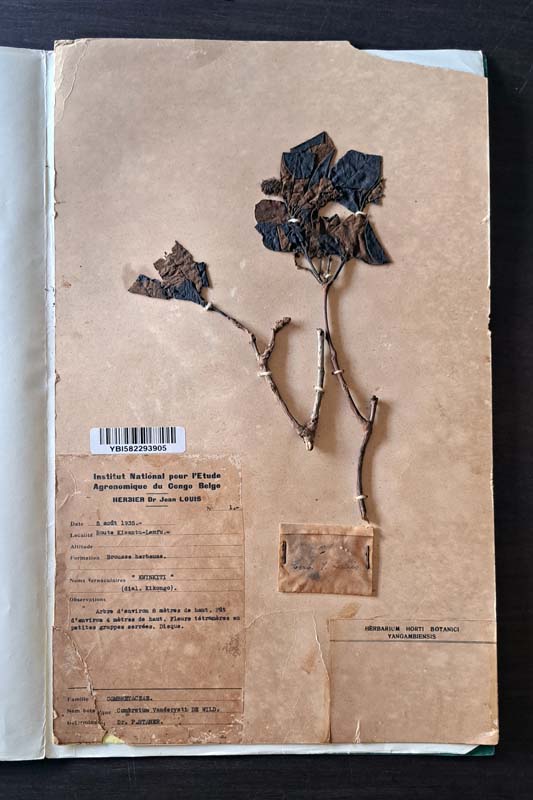

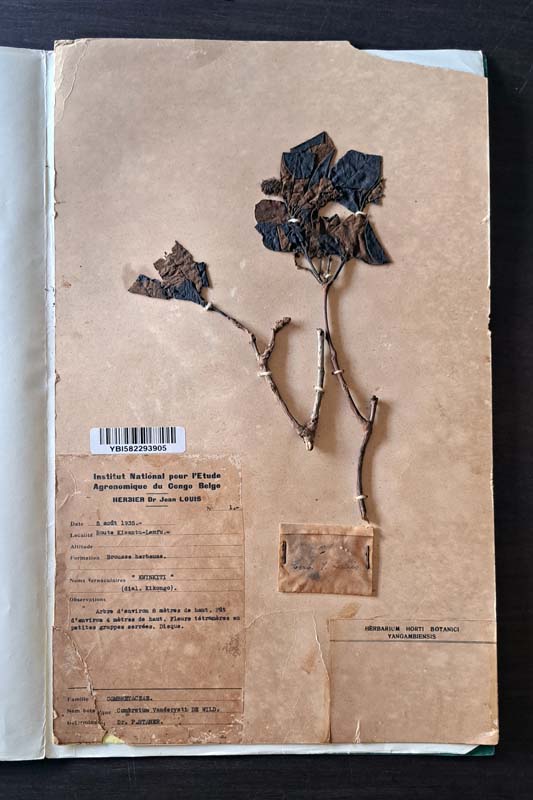

The National Herbarium of Yangambi hosts an impressive collection of plant species. An ongoing collaboration with the Meise Botanic Gardens, Belgium, has allowed for the digitization and preservation of the collection.

Kwinkiti leaves, the common name in Kikongo for a tree from the Combretaceae family. Collected in 1935 and stored in the Yangambi Herbarium.

The director of the INERA palm oil program welcomes me into his office. Hanging above the entrance door are photos of Beirnaert and Vanderweyen, two Belgian agronomists whom he calls the founding fathers of palm oil in Yangambi and Congo during the colonial era. There is a panel that schematically shows the year of planting for the various sectors in one of the second-generation plantations, established in the years around independence, between 1950 and 1964. This latter date is not coincidental. 1964 is the year when the Simba rebellion forced the last European technicians to leave Yangambi, leaving a void that, for two decades, due to the complete absence of qualified Congolese personnel—whose training was in no way a priority for the colonial government—left the entire center almost unused. But he says that now production is restarting, and he takes me to visit the newer plantations.

Inside INERA palm oil sector administrative office. Wooden panel representing the 2nd generation plantation in Beirnaertera, named after A. Beirnaert former director of the palm oil department.

Oil palm plants are germinated in specialized nurseries managed by INERA staff.

Access to the palm oil plantation via a path cut across the forest.

A 4th generation (planted in 1984) oil palm plantation. The spaces between the rows of plants are covered with a variety of leguminous plants to preserve the soil moisture.

Some plants are numbered, and their specifics are regularly monitored to select the best specimens for future plantations.

I realize that, during the weeks spent in Yangambi, I find myself looking at the landscape, the infrastructure, and the architecture with a gaze turned towards the past. And I regret it. In few other places in the Democratic Republic of Congo is the sense of nostalgia for the colonial past so clearly felt as it is here. In Lusanga, at the old Unilever plantation, nostalgia blends with a latent sense of revenge, of recognition that there, the colonisers had come to take the land and enjoyed its fruits undisturbed. But here, in Yangambi, this nostalgia seems undisputed. And somehow it embarrasses me, as I feel that every question I ask about the function of this or that building, often in a state of decay, makes me appear as someone retracing a nostalgic path through the history of a colonial jewel. I try to avoid giving such an impression, perhaps with little success, and yet I do not want to censor this feeling here. It’s part of its history and present too.

Looking at history through what is 'left on the ground', which is, after all, the purpose of these three months of travel, exposes one to this risk. And the recent history of the DRC, with its ambiguities and unresolved violent legacies, accentuates it. Viewing it through the prism of one of its material products, such as palm oil, tracing its production chain from the plantation, along the waterways through the ports, and into local and global markets, allows for mapping its spaces, architectures, and objects. It shows how palm oil has been a vector of contaminations for its role as a connector between local and global, an element rooted in traditional culture, but also a tool of exploitation, abuse, and a threat to environmental integrity. While this may not necessarily free us from preconceptions, it at least offers a fragmented and complex image that eludes extreme simplification.

Silos for storing palm oil in the former Yangambi industrial mill. The factory is located in what was the industrial district, which also comprised factories for coffee and natural rubber processing. The district is situated next to the river docks and gathered produce from several INEAC/INERA plantations. These products were shipped and sold worldwide.

Rails and the rotating system used for carts employed to move heavy loads within the industrial district.

Rows of workers houses in INERA’s residential quarters. The cités are scattered in various parts of the Yangambi site, located in proximity of plantations or industrial plants. While the houses were designed in a variety of typologies, they were all built using the characteristic bricks produced in the local brick factory owned by the Centre.

The ballroom, overlooking the Congo River, in the former staff club. The complex of buildings included a pool, a hotel, and a theater.

Read more of Michele's travel journal in "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future."

[i] Jackson, I; Harrison, E; Tenzon, M; Woudstra, R. (2024, forthcoming) The Architecture of United Africa, Bloomsbury

[ii] ’Foundation of Leverville’, Progress, 12:106, GB1752.LBL/3/1/2/10, UA, p. 53. Later journals’ entry clarify that this note was left by Mr. De Keyser – probably Henri Joseph Leon de Keyser, a Captain previously involved in a trial concerning his involvement in ‘Congo Free State atrocities’; HCB Inspector-General in the Upper Congo

[iii] ’Notes from the Congo: native labour at Leverville’, Progress, 12:107, GB1752.LBL/3/1/2/10, UA, p. 75-76.

[iv] ’News from Leverville’, Progress, 12:105, GB1752.LBL/3/1/2/10, UA, p.11-12(12).

[v] Marchal, J. (2008) Lord Leverhulme’s ghosts, Verso. First published in French as (2001) Travail force’ pour l’huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: l’histoire du Congo 1910-1945, vol.3, Paula Bellings.

[vi] Henriet, B. (2021) Colonial impotence: virtue and violence in a Congolese Concession (1911-1940), De Gruyter Oldenburg.

Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo

Jun 17, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this first installment of his travel blog, he traces the impacts of palm oil from Europe to The Democratic Republic of the Congo.

______________________________________________________________________

This study would not have been possible without the prior knowledge acquired through archival and fieldwork research during my years as a Research Associate at the University of Liverpool, as part of the research project ‘The Architecture of United

Africa’ (Ewan Harrison, Iain Jackson, Claire Tunstall, Rixt Woudstra).

Brussels

The Western world wages a battle against palm oil, and supermarket shelves are flooded with 'palm oil-free' labels. But for much of the Global South, palm oil is everywhere. It is in every household, every market, every port, and every forest. In Europe, where this journey of mine begins and ends, aside from its highlighted absence from the favorite biscuit’s brands, traces of palm oil in everyday life and spaces are rare. The yellow jerrycans that traditionally contains this oil and that are ubiquitous in African markets, are nowhere to be found in Europe. I personally had never used it in the kitchen, although, even if we don’t necessarily notice it, it is used in many personal care and cleaning products. Before I began visiting, in the past three or four years, West and Central Africa I had never seen an oil palm, let alone a plantation, and needless to say, I had no idea about the taste that palm oil lends to Congolese pondu or Ghanaian red red.

I remember stumbling upon palm oil for the first time in a natural science museum. The label affixed in front of a large bunch of reddish fruits installed in a display case stated that “from the pressing of the fruits of the oil palm, mainly spread in two species, Elaeis guineensis and Elaeis oleifera, varieties of oil are obtained for both food use and various industrial processes”. What the label didn’t say, and it would have been odd otherwise, is that, unlike in Europe, palm oil is everywhere at tropical latitudes. And that it serves as the vector for large-scale processes that have transformed entire urban and rural landscapes in the ‘oil palm belt,’ that part of the globe which includes much of West and Central Africa, Southeast Asia, and part of South America, where the climate and soil conditions are optimal for its cultivation.

Eleais Guineensis. The tree and its fruits

The other thing that the label did not say is that these bunches of firm fruits have been, at least for the past hundred years, at the center of contradictory tales of brutal exploitation and environmental controversies, but also of hope for progress and opportunity for change. They carry the weight of a heavy historical legacy that is reflected in their collective perception, both in the Global North and South, and which is impossible to dissociate from their physical impact on the land, the natural and built environments, and the lives of those who inhabit them.

Much later, after this initial encounter, I found myself wandering in an upscale neighborhood in Brussels, in Belgium, searching for a building that I knew had once served as the headquarters of an Anglo-Belgian-Congolese company engaged in the cultivation, extraction, and processing of palm oil. I had recently begun exploring the archives of this company, the Huileries du Congo Belge, a subsidiary of the commercial empire now known as Unilever, at its British headquarters in Port Sunlight, just a few kilometers from Liverpool. This company was exporting palm oil for use in soap production, including the famous Sunlight Soap.

Stone frieze depicting palm oil production process at the entrance of the Unilever House, European Quarter, Brussels, Belgium.

An ‘avenue’ in an oil palm plantation in the Belgian Congo, (1924) Au Pays des Palmiers, De Rycker.

During one of my frequent visits to Brussels, I decided to trace its footsteps among the city's architecture. Just steps away from the European Parliament, above the entrance of a rather nondescript office building, a stone frieze depicted the harvesting and processing of palm oil. A series of figures were portrayed in rigid poses, reminiscent of Egyptian bas-relief. At the end of the production chain, a factory worker delivers the product into the hands of a stylized Mercury, with a globe at his feet. Mercury, the god of shopkeepers and merchants, and the globe at his feet rhetorically symbolized the global aspirations of such an enterprise: gathering a natural resource from the most remote places to integrate it into the global capitalist circuit.

Indeed, if we were to follow the traces of this wandering Mercury, we would realize that palm oil has been and continues to be the intermediary in a chain of exchanges, commercial exploitations, and labor relations that have contributed to creating industrial and commercial empires around the globe. And yet, delving into the history of such agribusiness also means necessarily scratching beneath the rhetorical surface of the corporate and (neo)colonial narrative. Palm oil production and global trade have been, and continue to be, associated with labor exploitation, population displacement, abuse of the rights of local populations, and environmental degradation.

Even today, when palm oil accounts for over a third of the vegetable oil produced worldwide, its production and use are at the center of a decades-long controversy. On one hand, NGOs hold the palm oil industry responsible for environmental degradation, increasing poverty among indigenous peoples, and human rights abuses. On the other hand, independent scientists argue that the development of oil palm plantations can contribute to meeting the food needs of a growing global population and to a decline in rural poverty.

Resolving such a controversy is beyond my capabilities, but in this initial part of my journey, I glimpse the impact of this controversial agribusiness on everyday objects, public and private spaces, and natural and built environments. I sketch the material, architectural, and natural landscapes of palm oil. All of this, in one of the earliest epicenters of the surging demand for palm oil by the Western industry in the 20th century: the Democratic Republic of Congo, or simply the DRC.

Bare metal structures began to emerge since the early 1900s, protruding from the tropical vegetation background under the pressure of European colonial extractivism. Warehouses and workshops covered with corrugated iron sheets were constructed in countless locations to house the noisy machinery required to crack, press, and sterilize the reddish pulp and kernels of the palm fruits. Company towns were built to house the workers of its plantations and mills. Metal tanks to store and preserve the oil imposed their bulky silhouette in the main ports. Forests were cut and incinerated to make space for new plantations.

Kinshasa

[Linard] ––eh! l’huille de palme… palm oil, you use it for when you’re stung by ekonda. It’s an insect that doesn’t bite you but when you touch it, it gives you irritation to the skin. You put palm oil on it, and it helps. It’s good for the skin.

Sometimes you use it on the newborn babies because their skin is delicate. But it’s less common now.

And then, of course, you can’t make a good pondu [a popular stew made of pounded manioc leaves] without palm oil. And the tchaka madesu too. Manioc and beans.

Isn’t palm oil less used nowadays for food? – I ask to Linard – because of all the other vegetable oils that are imported. Sunflower, and, you know, all the rest…

––I’m not sure about that. Palm oil is a tradition here.

We're having this conversation while sipping a sucré at rond-point Luputa in Bandal, short for Bandalungwa, a neighborhood of Kinshasa, the capital city of the DRC. Some of the most meaningful encounters I've had in Kinshasa happened here, and Linard is a friend. His family owns a small palm oil plantation outside the city. I ask him some questions and explain how different the perception of a product so everyday for him is outside the continent we are on, and he nods in agreement.

Rond-Point Luputa, perhaps a strange place to ask this kind of question, is exactly what the name suggests: a roundabout. Definitely not the busiest crossroad in Kinshasa, a city of 20 million inhabitants, where the traffic and noise are so overwhelming that writing about it sounds redundant. During the day, cars are parked in the middle of the roundabout and moto-taxis circulate on the perimeter. But during the night, it becomes one of the busiest spots in the neighborhood as the parked cars are moved, the space is covered with tables, and the roadside gets filled with grilling boards and chikwanga sellers.

Bandal is informally called ‘Paris,’ but the sparse neon signs in Luputa say ‘Hotel États-Unis’ or ‘Cina Grill,’ contrasting with the pitch-black, largely electricity-less nights of Kinshasa. This disjointed whirlwind of geographical references brings me to mind the globe at the foot of Mercury, in that frieze I saw a few years ago in Brussels. And yet here in Kinshasa, this rhetoric of global aspiration seems much more amusing.

Palm oil jerrycans at the Matete market, Kinshasa

A few days later, the loads of yellow jerrycans that I see passing by on the street attract my attention. I go to visit the Matete market, one of the largest in the city. In a sector of this large, mostly open-air market, palm oil producers from Bas-Congo, as the now Kongo-central province is still called, or from Bandundu crowd with their trucks loaded with the plastic containers. The palm oil sector is just a space between buildings with controlled access, and wherever you look, everything is yellow-orange, stained with mud.

The overseer of one of the warehouses where jerrycans are gathered explains to me that producers come to them, unload their trucks, and wait until all their produce is sold, even if it means waiting for a week or two. They lie on the black muddy soil, using manioc leaf bags as pillows, under the shade of a simple porch made from metal sheets leaning against a cement brick wall. When all the oil is sold, they retrieve their containers and return to where they came from.

I'm also explained that the producers from Bas-Congo exploit artisanally, without machinery. All processing, from extraction to filtering is done manually in what are called palmeraies naturelles, natural palm groves, clusters of oil palm scattered in the forest. And while these are de facto cultivated, they defy the appearance of orderly arranged rows of plants that characterize plantations. On the contrary, producers from Bandundu exploit old and semi-abandoned plantations. But the lack of maintenance and the old age of the plants make them less productive.

His opinion is blunt: the quality of the produce from Bandundu’s old plantations is too low to be used as a food product and is generally sold to Marsavco, the only large soap-making factory left in Kinshasa and the heir to Huileries du Congo Belge, the business empire whose building still stands today in the institutional quarter of the European capital.

Satellite view of 'Camp PLZ,' the current name of the residential quarters for workers of the Huileries du Congo Belge, which was renamed Plantation Lever au Congo/Zaire. While the original barracks have been largely modified with additional volumes, the original arrangement is still clearly visible from above.

Lusanga

The produce from Bandundu in the Matete market came from a plantation complex that, at least until the era of Mobutu, was centered around a location known as Lusanga, and during the colonial period, as Leverville. 'Lever' - 'ville', named after William Lever, the founder of Huileries du Congo Belge and Unilever. As an African counterpart to the enlightened paternalism embodied by Port Sunlight, the company town founded by Lever on the outskirts of Liverpool, Leverville was meant to become the tangible symbol of the progress that European capitalism could bring to the heart of the Congolese forest. [i]

The settlement hosted one of the five palm oil plantation headquarters in the then Belgian Congo, as guaranteed by the agreement between Lever and the colonial government for the newly formed company. It was founded in 1911 when a small group of technicians sent there by the company landed at the confluence of the Kwilu and Kwenge rivers and laid out its main axes according to a symmetrical scheme of avenues stemming from the river docks. These avenues continued fading into the horizon and seemed to symbolize the propagation of progress from the mill towards the untouched forest.

Depiction of Leverville’s docks. The avenues fading in the forest are visible in the background. https://autoitaliasoutheast.org/rwba/interior-ecosystems-kristin-luke-employee-workshops-where-objects-are-fabricated/

Alberta, in the foreground, and on the opposite side of the river, Leverville, two of the plantations owned and managed by HCB, as represented in a diorama for the Belgian Colonial Palace at the 1913 Ghent International Exhibition. In reality, the two plantations were thousands of kilometers apart. (Source: Progress magazine, Issue 14, p.116).

According to the romanticized accounts from the pages of one of the company magazines, which tells the story of the foundation of Leverville with all the exoticizing tropes of colonial literature, the settlement was founded on a "splendid site [which] rises in a slight slope from the river toward the interior, and is covered with magnificent palm trees laden with fruit." [ii] These diaries describe how initially, a group of over 40 laborers worked on clearing the land and constructing two houses and a native hangar. Within a month, they had cleared "more than sufficient ground for the needs of Leverville in the near future." [iii] The journals further recount the initial travels of functionaries in the Lusanga area, praising the natural riches of the region. They describe it as having "park-like, bright, grassy spaces on undulating hills, with clumps of palm and wood," and note the presence of oil palms extending for miles inland. [iv]

To tell the truth, to an eye not accustomed to agronomy like mine, such richness of palm oil went unnoticed. Or perhaps my perspective is shaped by the fact that, starting in the 1920s, the company’s own technicians realized that this natural abundance was mostly a mirage. But from the vantage point of the hill where the European quarters of Lusanga were installed, you can see the undulating landscape enclosed by the confluence of the two rivers. And the scenery is indeed magnificent.

View of the Kwilu river from Lusanga

Mural paintings representing palm oil gathering and transport. The paintings are inside the Cercle Elaeïs, the private club of senior Unilever workers in Lusanga. Benoit Henriet dates the murals in the building to 1989 and attributes them to Sissi Kalo.

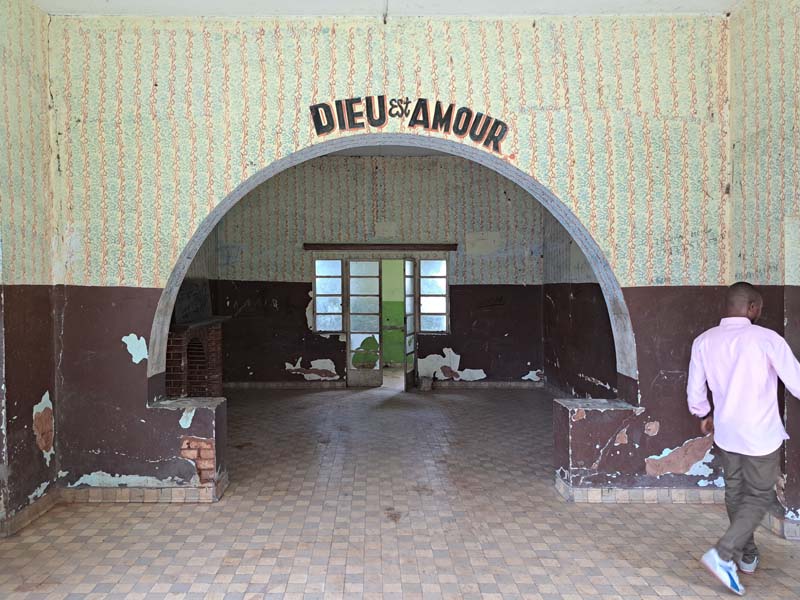

The Church of the Catholic Mission in Banga Banga, Lusanga. The mission was originally funded by HCB and managed the schools built in proximity to the palm oil mills, as established in the Convention between HCB and the Belgian colonial government.

When I visit Lusanga for the first time, my experience cannot help but be influenced by the accounts of historians such as Jules Marchal [v] and Benoit Henriet [vi], who detailed the brutality of Lever Brother’s exploitation, especially in the Belgian Congo, the forced resettlement of the local population, and the violent repression of “uncooperative workers.”

I am staying in one of the missions originally funded by Huileries du Congo Belge, and one of the local directors of the new company that now owns the site, after Unilever definitively abandoned it in the 1990s, is accompanying me on the visit. In fact, a visit would not have been possible without his permission and guidance. The company, indeed, far from being simply an actor among others active in the area, and similarly to the previous Anglo-Belgian ownership. was perceived by everyone in the village—from the inhabitants and the local authorities with whom I could talk, to the missionaries who hosted me in their foyer—as essentially the ‘owner of the place’.

The company owned not only the forest land, the plantations, the administrative buildings, and the warehouses located next to what were once the main river docks of Lusanga at the confluence between the Kwilu and Kwenge rivers. It also owned the rows of villas aligned along the riverbanks, the ten or twenty halls and dormitories and buildings, some of them now completely abandoned of what is still called l’hopital Européen – the hospital for the Europeans – and the hundreds of houses, arranged in rows along series of parallel, large avenues built in various phases to host the plantation workers.

Exterior and interior views of the now derelict Hopital Européen built in the 1950s.

My guide lived in one of the villas for the European managers. Despite the company employs nowadays only Congolese managers and workers, the social and functional segregation in Lusanga seems to accurately retrace that of its first establishment, a century before. The company managers occupied the spaces conceived for the colonizers and the workers’ houses separated by a cordon sanitaire. Except for the fact that nowadays there are no Belgian, Dutch, British or Italian managers, and the racial segregation has been substituted by class segregation.

A worker's house in Lusanga. This residential typology hosted a specific category of Congolese skilled workers who, having received some formal education, were called, in colonial jargon, "évolué," literally meaning 'evolved.' The expression is still widely used in the DRC.

House originally intended for the European functionaries. Lusanga.

Yangambi

The continuation of my journey takes me to the opposite side of the DRC, to Yangambi, along the Congo River, home to the largest agronomic research center in the country, the Institut National pour l'Étude Agronomique du Congo Belge (INERA). Following the course of the river downstream from Kisangani, one can understand why, in 1933, it was decided to establish what was then called the Institut National pour l'Étude Agronomique du Congo Belge in this location. After two or three hours of fast navigation along nearly flat banks, the river, crossed lengthwise by oblong islets, resembles a lake even more as the expanse of water widens. And the banks become steep, offering a terrace rising several dozen meters above the river level, on which the first rows of Yangambi's buildings scenically overlook.

The INERA is a vast complex of facilities, research laboratories, training centers, specialized libraries, and herbaria, but also trial gardens, and experimental plantations that make it a sprawling complex, surrounded by an extensive forest reserve. The palm oil sector of this research center is, or at least was, one of its crown jewels, as long as the colonial extractive economy financed its costs. It provided the seeds along with the training of specialized technicians for almost all the plantations in the country, including Lusanga.

Far from the traditional image of a university campus or research center, it is a site that spans nearly 25,000 hectares and includes, in addition to administrative and research buildings, a collection of scattered villas and residential quarters that accommodated the more than 10,000 people employed at its peak. During this time, the production and processing of palm oil, natural rubber, cocoa, and coffee for commercial purposes financed a thriving activity of selection and adaptation of plant species, which for decades were sent to establish the primary plant group for plantations located all over the world in tropical latitudes.

A large map (approximately 2 by 3 meters) of the INERA premises in Yangambi painted on a thin layer of wood. The map, dated 1954 and signed ‘Demolin’, is hung in the entry hall of the main administrative building of INERA, which also contains its library and archives.

The library's old cataloging system, arranged by topic.

The National Herbarium of Yangambi hosts an impressive collection of plant species. An ongoing collaboration with the Meise Botanic Gardens, Belgium, has allowed for the digitization and preservation of the collection.

Kwinkiti leaves, the common name in Kikongo for a tree from the Combretaceae family. Collected in 1935 and stored in the Yangambi Herbarium.

The director of the INERA palm oil program welcomes me into his office. Hanging above the entrance door are photos of Beirnaert and Vanderweyen, two Belgian agronomists whom he calls the founding fathers of palm oil in Yangambi and Congo during the colonial era. There is a panel that schematically shows the year of planting for the various sectors in one of the second-generation plantations, established in the years around independence, between 1950 and 1964. This latter date is not coincidental. 1964 is the year when the Simba rebellion forced the last European technicians to leave Yangambi, leaving a void that, for two decades, due to the complete absence of qualified Congolese personnel—whose training was in no way a priority for the colonial government—left the entire center almost unused. But he says that now production is restarting, and he takes me to visit the newer plantations.

Inside INERA palm oil sector administrative office. Wooden panel representing the 2nd generation plantation in Beirnaertera, named after A. Beirnaert former director of the palm oil department.

Oil palm plants are germinated in specialized nurseries managed by INERA staff.

Access to the palm oil plantation via a path cut across the forest.

A 4th generation (planted in 1984) oil palm plantation. The spaces between the rows of plants are covered with a variety of leguminous plants to preserve the soil moisture.

Some plants are numbered, and their specifics are regularly monitored to select the best specimens for future plantations.

I realize that, during the weeks spent in Yangambi, I find myself looking at the landscape, the infrastructure, and the architecture with a gaze turned towards the past. And I regret it. In few other places in the Democratic Republic of Congo is the sense of nostalgia for the colonial past so clearly felt as it is here. In Lusanga, at the old Unilever plantation, nostalgia blends with a latent sense of revenge, of recognition that there, the colonisers had come to take the land and enjoyed its fruits undisturbed. But here, in Yangambi, this nostalgia seems undisputed. And somehow it embarrasses me, as I feel that every question I ask about the function of this or that building, often in a state of decay, makes me appear as someone retracing a nostalgic path through the history of a colonial jewel. I try to avoid giving such an impression, perhaps with little success, and yet I do not want to censor this feeling here. It’s part of its history and present too.

Looking at history through what is 'left on the ground', which is, after all, the purpose of these three months of travel, exposes one to this risk. And the recent history of the DRC, with its ambiguities and unresolved violent legacies, accentuates it. Viewing it through the prism of one of its material products, such as palm oil, tracing its production chain from the plantation, along the waterways through the ports, and into local and global markets, allows for mapping its spaces, architectures, and objects. It shows how palm oil has been a vector of contaminations for its role as a connector between local and global, an element rooted in traditional culture, but also a tool of exploitation, abuse, and a threat to environmental integrity. While this may not necessarily free us from preconceptions, it at least offers a fragmented and complex image that eludes extreme simplification.

Silos for storing palm oil in the former Yangambi industrial mill. The factory is located in what was the industrial district, which also comprised factories for coffee and natural rubber processing. The district is situated next to the river docks and gathered produce from several INEAC/INERA plantations. These products were shipped and sold worldwide.

Rails and the rotating system used for carts employed to move heavy loads within the industrial district.

Rows of workers houses in INERA’s residential quarters. The cités are scattered in various parts of the Yangambi site, located in proximity of plantations or industrial plants. While the houses were designed in a variety of typologies, they were all built using the characteristic bricks produced in the local brick factory owned by the Centre.

The ballroom, overlooking the Congo River, in the former staff club. The complex of buildings included a pool, a hotel, and a theater.

Read more of Michele's travel journal in "Tanzania: Dreams and Failures of a Rural Future."

[i] Jackson, I; Harrison, E; Tenzon, M; Woudstra, R. (2024, forthcoming) The Architecture of United Africa, Bloomsbury

[ii] ’Foundation of Leverville’, Progress, 12:106, GB1752.LBL/3/1/2/10, UA, p. 53. Later journals’ entry clarify that this note was left by Mr. De Keyser – probably Henri Joseph Leon de Keyser, a Captain previously involved in a trial concerning his involvement in ‘Congo Free State atrocities’; HCB Inspector-General in the Upper Congo

[iii] ’Notes from the Congo: native labour at Leverville’, Progress, 12:107, GB1752.LBL/3/1/2/10, UA, p. 75-76.

[iv] ’News from Leverville’, Progress, 12:105, GB1752.LBL/3/1/2/10, UA, p.11-12(12).

[v] Marchal, J. (2008) Lord Leverhulme’s ghosts, Verso. First published in French as (2001) Travail force’ pour l’huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: l’histoire du Congo 1910-1945, vol.3, Paula Bellings.

[vi] Henriet, B. (2021) Colonial impotence: virtue and violence in a Congolese Concession (1911-1940), De Gruyter Oldenburg.

2024 Recipients

Palm Oil Landscapes in DR Congo

Jun 17, 2024

by

Michele Tenzon, recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Architect and architectural historian Michele Tenzon is a lecturer at École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires in Paris. His research focuses on the effects of agricultural development on the built environment in colonial and postcolonial contexts. He holds a PhD from Université libre de Bruxelles and master’s degrees in architectural history and architecture from the University College of London and the University of Ferrara.

As a recipient of the 2024 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Tenzon is researching the development of palm oil and groundnuts as industrial crops in the 20th century and the impact of that industry on the rural and urban landscape of colonial and post-colonial Africa. In this first installment of his travel blog, he traces the impacts of palm oil from Europe to The Democratic Republic of the Congo.

______________________________________________________________________

This study would not have been possible without the prior knowledge acquired through archival and fieldwork research during my years as a Research Associate at the University of Liverpool, as part of the research project ‘The Architecture of United

Africa’ (Ewan Harrison, Iain Jackson, Claire Tunstall, Rixt Woudstra).

Brussels

The Western world wages a battle against palm oil, and supermarket shelves are flooded with 'palm oil-free' labels. But for much of the Global South, palm oil is everywhere. It is in every household, every market, every port, and every forest. In Europe, where this journey of mine begins and ends, aside from its highlighted absence from the favorite biscuit’s brands, traces of palm oil in everyday life and spaces are rare. The yellow jerrycans that traditionally contains this oil and that are ubiquitous in African markets, are nowhere to be found in Europe. I personally had never used it in the kitchen, although, even if we don’t necessarily notice it, it is used in many personal care and cleaning products. Before I began visiting, in the past three or four years, West and Central Africa I had never seen an oil palm, let alone a plantation, and needless to say, I had no idea about the taste that palm oil lends to Congolese pondu or Ghanaian red red.

I remember stumbling upon palm oil for the first time in a natural science museum. The label affixed in front of a large bunch of reddish fruits installed in a display case stated that “from the pressing of the fruits of the oil palm, mainly spread in two species, Elaeis guineensis and Elaeis oleifera, varieties of oil are obtained for both food use and various industrial processes”. What the label didn’t say, and it would have been odd otherwise, is that, unlike in Europe, palm oil is everywhere at tropical latitudes. And that it serves as the vector for large-scale processes that have transformed entire urban and rural landscapes in the ‘oil palm belt,’ that part of the globe which includes much of West and Central Africa, Southeast Asia, and part of South America, where the climate and soil conditions are optimal for its cultivation.

Eleais Guineensis. The tree and its fruits

The other thing that the label did not say is that these bunches of firm fruits have been, at least for the past hundred years, at the center of contradictory tales of brutal exploitation and environmental controversies, but also of hope for progress and opportunity for change. They carry the weight of a heavy historical legacy that is reflected in their collective perception, both in the Global North and South, and which is impossible to dissociate from their physical impact on the land, the natural and built environments, and the lives of those who inhabit them.

Much later, after this initial encounter, I found myself wandering in an upscale neighborhood in Brussels, in Belgium, searching for a building that I knew had once served as the headquarters of an Anglo-Belgian-Congolese company engaged in the cultivation, extraction, and processing of palm oil. I had recently begun exploring the archives of this company, the Huileries du Congo Belge, a subsidiary of the commercial empire now known as Unilever, at its British headquarters in Port Sunlight, just a few kilometers from Liverpool. This company was exporting palm oil for use in soap production, including the famous Sunlight Soap.

Stone frieze depicting palm oil production process at the entrance of the Unilever House, European Quarter, Brussels, Belgium.

An ‘avenue’ in an oil palm plantation in the Belgian Congo, (1924) Au Pays des Palmiers, De Rycker.

During one of my frequent visits to Brussels, I decided to trace its footsteps among the city's architecture. Just steps away from the European Parliament, above the entrance of a rather nondescript office building, a stone frieze depicted the harvesting and processing of palm oil. A series of figures were portrayed in rigid poses, reminiscent of Egyptian bas-relief. At the end of the production chain, a factory worker delivers the product into the hands of a stylized Mercury, with a globe at his feet. Mercury, the god of shopkeepers and merchants, and the globe at his feet rhetorically symbolized the global aspirations of such an enterprise: gathering a natural resource from the most remote places to integrate it into the global capitalist circuit.

Indeed, if we were to follow the traces of this wandering Mercury, we would realize that palm oil has been and continues to be the intermediary in a chain of exchanges, commercial exploitations, and labor relations that have contributed to creating industrial and commercial empires around the globe. And yet, delving into the history of such agribusiness also means necessarily scratching beneath the rhetorical surface of the corporate and (neo)colonial narrative. Palm oil production and global trade have been, and continue to be, associated with labor exploitation, population displacement, abuse of the rights of local populations, and environmental degradation.

Even today, when palm oil accounts for over a third of the vegetable oil produced worldwide, its production and use are at the center of a decades-long controversy. On one hand, NGOs hold the palm oil industry responsible for environmental degradation, increasing poverty among indigenous peoples, and human rights abuses. On the other hand, independent scientists argue that the development of oil palm plantations can contribute to meeting the food needs of a growing global population and to a decline in rural poverty.

Resolving such a controversy is beyond my capabilities, but in this initial part of my journey, I glimpse the impact of this controversial agribusiness on everyday objects, public and private spaces, and natural and built environments. I sketch the material, architectural, and natural landscapes of palm oil. All of this, in one of the earliest epicenters of the surging demand for palm oil by the Western industry in the 20th century: the Democratic Republic of Congo, or simply the DRC.

Bare metal structures began to emerge since the early 1900s, protruding from the tropical vegetation background under the pressure of European colonial extractivism. Warehouses and workshops covered with corrugated iron sheets were constructed in countless locations to house the noisy machinery required to crack, press, and sterilize the reddish pulp and kernels of the palm fruits. Company towns were built to house the workers of its plantations and mills. Metal tanks to store and preserve the oil imposed their bulky silhouette in the main ports. Forests were cut and incinerated to make space for new plantations.

Kinshasa

[Linard] ––eh! l’huille de palme… palm oil, you use it for when you’re stung by ekonda. It’s an insect that doesn’t bite you but when you touch it, it gives you irritation to the skin. You put palm oil on it, and it helps. It’s good for the skin.

Sometimes you use it on the newborn babies because their skin is delicate. But it’s less common now.

And then, of course, you can’t make a good pondu [a popular stew made of pounded manioc leaves] without palm oil. And the tchaka madesu too. Manioc and beans.

Isn’t palm oil less used nowadays for food? – I ask to Linard – because of all the other vegetable oils that are imported. Sunflower, and, you know, all the rest…

––I’m not sure about that. Palm oil is a tradition here.

We're having this conversation while sipping a sucré at rond-point Luputa in Bandal, short for Bandalungwa, a neighborhood of Kinshasa, the capital city of the DRC. Some of the most meaningful encounters I've had in Kinshasa happened here, and Linard is a friend. His family owns a small palm oil plantation outside the city. I ask him some questions and explain how different the perception of a product so everyday for him is outside the continent we are on, and he nods in agreement.

Rond-Point Luputa, perhaps a strange place to ask this kind of question, is exactly what the name suggests: a roundabout. Definitely not the busiest crossroad in Kinshasa, a city of 20 million inhabitants, where the traffic and noise are so overwhelming that writing about it sounds redundant. During the day, cars are parked in the middle of the roundabout and moto-taxis circulate on the perimeter. But during the night, it becomes one of the busiest spots in the neighborhood as the parked cars are moved, the space is covered with tables, and the roadside gets filled with grilling boards and chikwanga sellers.

Bandal is informally called ‘Paris,’ but the sparse neon signs in Luputa say ‘Hotel États-Unis’ or ‘Cina Grill,’ contrasting with the pitch-black, largely electricity-less nights of Kinshasa. This disjointed whirlwind of geographical references brings me to mind the globe at the foot of Mercury, in that frieze I saw a few years ago in Brussels. And yet here in Kinshasa, this rhetoric of global aspiration seems much more amusing.

Palm oil jerrycans at the Matete market, Kinshasa

A few days later, the loads of yellow jerrycans that I see passing by on the street attract my attention. I go to visit the Matete market, one of the largest in the city. In a sector of this large, mostly open-air market, palm oil producers from Bas-Congo, as the now Kongo-central province is still called, or from Bandundu crowd with their trucks loaded with the plastic containers. The palm oil sector is just a space between buildings with controlled access, and wherever you look, everything is yellow-orange, stained with mud.

The overseer of one of the warehouses where jerrycans are gathered explains to me that producers come to them, unload their trucks, and wait until all their produce is sold, even if it means waiting for a week or two. They lie on the black muddy soil, using manioc leaf bags as pillows, under the shade of a simple porch made from metal sheets leaning against a cement brick wall. When all the oil is sold, they retrieve their containers and return to where they came from.

I'm also explained that the producers from Bas-Congo exploit artisanally, without machinery. All processing, from extraction to filtering is done manually in what are called palmeraies naturelles, natural palm groves, clusters of oil palm scattered in the forest. And while these are de facto cultivated, they defy the appearance of orderly arranged rows of plants that characterize plantations. On the contrary, producers from Bandundu exploit old and semi-abandoned plantations. But the lack of maintenance and the old age of the plants make them less productive.

His opinion is blunt: the quality of the produce from Bandundu’s old plantations is too low to be used as a food product and is generally sold to Marsavco, the only large soap-making factory left in Kinshasa and the heir to Huileries du Congo Belge, the business empire whose building still stands today in the institutional quarter of the European capital.

Satellite view of 'Camp PLZ,' the current name of the residential quarters for workers of the Huileries du Congo Belge, which was renamed Plantation Lever au Congo/Zaire. While the original barracks have been largely modified with additional volumes, the original arrangement is still clearly visible from above.

Lusanga

The produce from Bandundu in the Matete market came from a plantation complex that, at least until the era of Mobutu, was centered around a location known as Lusanga, and during the colonial period, as Leverville. 'Lever' - 'ville', named after William Lever, the founder of Huileries du Congo Belge and Unilever. As an African counterpart to the enlightened paternalism embodied by Port Sunlight, the company town founded by Lever on the outskirts of Liverpool, Leverville was meant to become the tangible symbol of the progress that European capitalism could bring to the heart of the Congolese forest. [i]

The settlement hosted one of the five palm oil plantation headquarters in the then Belgian Congo, as guaranteed by the agreement between Lever and the colonial government for the newly formed company. It was founded in 1911 when a small group of technicians sent there by the company landed at the confluence of the Kwilu and Kwenge rivers and laid out its main axes according to a symmetrical scheme of avenues stemming from the river docks. These avenues continued fading into the horizon and seemed to symbolize the propagation of progress from the mill towards the untouched forest.

Depiction of Leverville’s docks. The avenues fading in the forest are visible in the background. https://autoitaliasoutheast.org/rwba/interior-ecosystems-kristin-luke-employee-workshops-where-objects-are-fabricated/

Alberta, in the foreground, and on the opposite side of the river, Leverville, two of the plantations owned and managed by HCB, as represented in a diorama for the Belgian Colonial Palace at the 1913 Ghent International Exhibition. In reality, the two plantations were thousands of kilometers apart. (Source: Progress magazine, Issue 14, p.116).

According to the romanticized accounts from the pages of one of the company magazines, which tells the story of the foundation of Leverville with all the exoticizing tropes of colonial literature, the settlement was founded on a "splendid site [which] rises in a slight slope from the river toward the interior, and is covered with magnificent palm trees laden with fruit." [ii] These diaries describe how initially, a group of over 40 laborers worked on clearing the land and constructing two houses and a native hangar. Within a month, they had cleared "more than sufficient ground for the needs of Leverville in the near future." [iii] The journals further recount the initial travels of functionaries in the Lusanga area, praising the natural riches of the region. They describe it as having "park-like, bright, grassy spaces on undulating hills, with clumps of palm and wood," and note the presence of oil palms extending for miles inland. [iv]

To tell the truth, to an eye not accustomed to agronomy like mine, such richness of palm oil went unnoticed. Or perhaps my perspective is shaped by the fact that, starting in the 1920s, the company’s own technicians realized that this natural abundance was mostly a mirage. But from the vantage point of the hill where the European quarters of Lusanga were installed, you can see the undulating landscape enclosed by the confluence of the two rivers. And the scenery is indeed magnificent.

View of the Kwilu river from Lusanga

Mural paintings representing palm oil gathering and transport. The paintings are inside the Cercle Elaeïs, the private club of senior Unilever workers in Lusanga. Benoit Henriet dates the murals in the building to 1989 and attributes them to Sissi Kalo.

The Church of the Catholic Mission in Banga Banga, Lusanga. The mission was originally funded by HCB and managed the schools built in proximity to the palm oil mills, as established in the Convention between HCB and the Belgian colonial government.

When I visit Lusanga for the first time, my experience cannot help but be influenced by the accounts of historians such as Jules Marchal [v] and Benoit Henriet [vi], who detailed the brutality of Lever Brother’s exploitation, especially in the Belgian Congo, the forced resettlement of the local population, and the violent repression of “uncooperative workers.”

I am staying in one of the missions originally funded by Huileries du Congo Belge, and one of the local directors of the new company that now owns the site, after Unilever definitively abandoned it in the 1990s, is accompanying me on the visit. In fact, a visit would not have been possible without his permission and guidance. The company, indeed, far from being simply an actor among others active in the area, and similarly to the previous Anglo-Belgian ownership. was perceived by everyone in the village—from the inhabitants and the local authorities with whom I could talk, to the missionaries who hosted me in their foyer—as essentially the ‘owner of the place’.

The company owned not only the forest land, the plantations, the administrative buildings, and the warehouses located next to what were once the main river docks of Lusanga at the confluence between the Kwilu and Kwenge rivers. It also owned the rows of villas aligned along the riverbanks, the ten or twenty halls and dormitories and buildings, some of them now completely abandoned of what is still called l’hopital Européen – the hospital for the Europeans – and the hundreds of houses, arranged in rows along series of parallel, large avenues built in various phases to host the plantation workers.

Exterior and interior views of the now derelict Hopital Européen built in the 1950s.

My guide lived in one of the villas for the European managers. Despite the company employs nowadays only Congolese managers and workers, the social and functional segregation in Lusanga seems to accurately retrace that of its first establishment, a century before. The company managers occupied the spaces conceived for the colonizers and the workers’ houses separated by a cordon sanitaire. Except for the fact that nowadays there are no Belgian, Dutch, British or Italian managers, and the racial segregation has been substituted by class segregation.

A worker's house in Lusanga. This residential typology hosted a specific category of Congolese skilled workers who, having received some formal education, were called, in colonial jargon, "évolué," literally meaning 'evolved.' The expression is still widely used in the DRC.

House originally intended for the European functionaries. Lusanga.

Yangambi

The continuation of my journey takes me to the opposite side of the DRC, to Yangambi, along the Congo River, home to the largest agronomic research center in the country, the Institut National pour l'Étude Agronomique du Congo Belge (INERA). Following the course of the river downstream from Kisangani, one can understand why, in 1933, it was decided to establish what was then called the Institut National pour l'Étude Agronomique du Congo Belge in this location. After two or three hours of fast navigation along nearly flat banks, the river, crossed lengthwise by oblong islets, resembles a lake even more as the expanse of water widens. And the banks become steep, offering a terrace rising several dozen meters above the river level, on which the first rows of Yangambi's buildings scenically overlook.

The INERA is a vast complex of facilities, research laboratories, training centers, specialized libraries, and herbaria, but also trial gardens, and experimental plantations that make it a sprawling complex, surrounded by an extensive forest reserve. The palm oil sector of this research center is, or at least was, one of its crown jewels, as long as the colonial extractive economy financed its costs. It provided the seeds along with the training of specialized technicians for almost all the plantations in the country, including Lusanga.

Far from the traditional image of a university campus or research center, it is a site that spans nearly 25,000 hectares and includes, in addition to administrative and research buildings, a collection of scattered villas and residential quarters that accommodated the more than 10,000 people employed at its peak. During this time, the production and processing of palm oil, natural rubber, cocoa, and coffee for commercial purposes financed a thriving activity of selection and adaptation of plant species, which for decades were sent to establish the primary plant group for plantations located all over the world in tropical latitudes.

A large map (approximately 2 by 3 meters) of the INERA premises in Yangambi painted on a thin layer of wood. The map, dated 1954 and signed ‘Demolin’, is hung in the entry hall of the main administrative building of INERA, which also contains its library and archives.

The library's old cataloging system, arranged by topic.

The National Herbarium of Yangambi hosts an impressive collection of plant species. An ongoing collaboration with the Meise Botanic Gardens, Belgium, has allowed for the digitization and preservation of the collection.

Kwinkiti leaves, the common name in Kikongo for a tree from the Combretaceae family. Collected in 1935 and stored in the Yangambi Herbarium.

The director of the INERA palm oil program welcomes me into his office. Hanging above the entrance door are photos of Beirnaert and Vanderweyen, two Belgian agronomists whom he calls the founding fathers of palm oil in Yangambi and Congo during the colonial era. There is a panel that schematically shows the year of planting for the various sectors in one of the second-generation plantations, established in the years around independence, between 1950 and 1964. This latter date is not coincidental. 1964 is the year when the Simba rebellion forced the last European technicians to leave Yangambi, leaving a void that, for two decades, due to the complete absence of qualified Congolese personnel—whose training was in no way a priority for the colonial government—left the entire center almost unused. But he says that now production is restarting, and he takes me to visit the newer plantations.

Inside INERA palm oil sector administrative office. Wooden panel representing the 2nd generation plantation in Beirnaertera, named after A. Beirnaert former director of the palm oil department.

Oil palm plants are germinated in specialized nurseries managed by INERA staff.

Access to the palm oil plantation via a path cut across the forest.

A 4th generation (planted in 1984) oil palm plantation. The spaces between the rows of plants are covered with a variety of leguminous plants to preserve the soil moisture.

Some plants are numbered, and their specifics are regularly monitored to select the best specimens for future plantations.