-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Phantom of Empire: Stagecraft in Qing Court Production of Art and Theater, 1700-1827

Aug 2, 2024

by

Tong Su, recipient of 2023 SAH Dissertation Fellowship

Tong Su is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research focuses on the art and urbanism of late imperial China from the 17th to the 19th century. Her dissertation examines the design of theater and performance space in relation to the state building during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

Before pursuing her doctoral degree at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she achieved cross-disciplinary education and degrees in digital animation, art and architectural history, and other areas of arts and humanities from the University of Chicago (MA in Humanities), Maryland Institute College of Art (MFA in Illustration Practice), and Nanyang Technological University Singapore (BFA in Digital Animation).

The performance culture of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) was a rich array of musical and theatrical repertory that played important roles in the dynasty’s quest for power and unity. Qing’s deep appreciation for the performing arts was linked to its historical identity as an ethnic minority positioned low in the ritual hierarchy of the Confucian worldview. Recognizing the influence of musical and theatrical performances in elevating their status, Qing leaders utilized them as instruments of governance. Their objectives included bolstering their martial image and international prestige, as well as integrating marginalized ethnic subcultures, including the native Manchu, into the prevailing cultural narrative. Choreographing the moment and the space of performance to captivate diverse Qing audiences and reinforce the dynasty’s dominion held ruling significance in the visual culture and building history of the dynasty.

Unlike the relatively lax governance of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922), which relied mainly on taxation outside Turkey, the Qing empire’s stability was bolstered by diverse integrative mechanisms.[1] Historian Joanna Waley-Cohen highlights how the normalization of military and war culture in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries encouraged descendants to embrace the martial spirit, fostering a sense of community and forging a new collective identity among Qing subjects.[2] While Waley-Cohen underscores the significance of urban facilities, military rituals and exercises, and war monuments in building communal bonds, my study shifts focus to explore how the dynastic power was bolstered and perpetuated through an evolving performance culture. This vivid performance culture transformed the physical landscape through temporary architectural structures and stage props. Amidst the conquest wars, performative stagecraft was a strategic instrument of Qing rulership.[3]

Through a centralized strategy, the Qing rulership solidified their authority via a performance culture enriched by cultural diversity and expression, while simultaneously cultivating a dynamic power network, given that the initiative of performance was inherently collaborative. The active engagement in mitigating community divisions in this performance culture indicates that stagecraft served dual functions: as both an art form and a governance tool. Striking a fine balance between order and magnificence, the representation of songs, dances, and storytelling performances on stages transitioned from extravagant entertainment to powerful symbols of loyalty and unity.

Qing’s Systematic Approach to the Production of Performance

The current historiography of Qing court theater production is based on archival research of court administrative documents from the Imperial Household Department, a Qing institution managing the internal affairs of the imperial family and the activities of the inner palace, combined with literature analysis of playscripts preserved in the Qing court collection.[4] While these sources provide an understanding of the variety of performance-related texts held at court, current scholarship does not sufficiently explain how Qing performance culture reshaped the physical landscape within and beyond the imperial palace. The broader impact of performance on the physical landscape and the rhythms of social life requires further emphasis and clear delineation.

Qing’s nation-wide labor network for art and architecture productions, including stage architecture and props involved in performance, was established in the late seventeenth century.[5] This labor network was organized into specialized departments based on craftsmen’s expertise and knowledge of production, forming a technocratic system within the political formation of Qing bureaucracy. In addition to the departments managing specialized labor, the Grand Council, originally established to manage Qing military affairs in 1733 by the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1722-1735), began overseeing national ceremonial events, including imperial birthday celebrations, starting no later than 1751 during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r.1735-1796). These events required extensive planning and cross-regional collaboration by labor units responsible for organizing performances and constructing stage architecture. The imperial decrees issued through the Grand Council to mobilize people and resources for these celebrations are preserved at the First Historical Archives of China. Concurrently, numerous letters composed of rhymed verses, written in both Chinese and Manchu and sent from regional governors to the emperors conveying birthday wishes, are also preserved at the Archives.

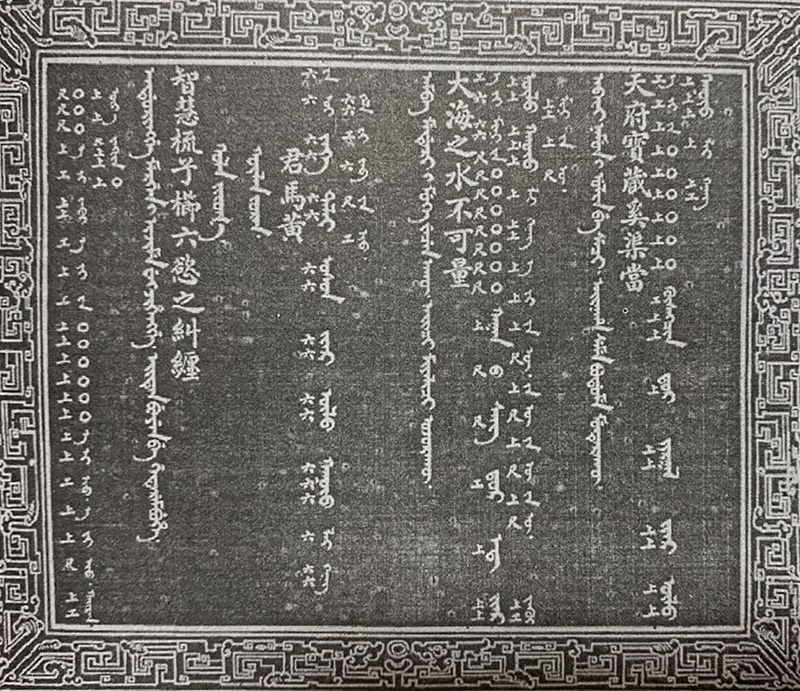

Figure 1. Song scripts of “kūlan joran” or brown ambler horse, with Chinese musical notation. Photocopy.

The use of rhymed verses in these letters was closely tied to the reverence for the ceremonial occasions of imperial rulers’ birthdays. They possess a formalized tone and share vocabulary with musical verses expressing auspicious wishes. These letters led me to historical records indicating that, besides Chinese, the incorporation of Manchu verses expanded the national repertoire of ceremonial musical performances. My dissertation fieldwork involved translating some Manchu verses used in theatrical performances, many of which were inherited from Mongol music and celebrated martial prowess (Figure

1)

. The syllabic nature of Manchu, as opposed to the logographic Chinese, diversified the dynasty’s musical language and enriched its martial overtones of unification. The staging of these multivocal performances symbolized cultural and ethnic encounters. Musical performances at these events were not merely for entertainment but were formalized acts of ceremonial significance in unifying diverse cultures. Such archival records helped define the scope of the Qing empire’s cultural readaptation from the perspective of performance culture, reflected in its growing repertoire of performative traditions incorporated during the process of conquest.

Performance Architecture in the Scope of Chinese Building Practices

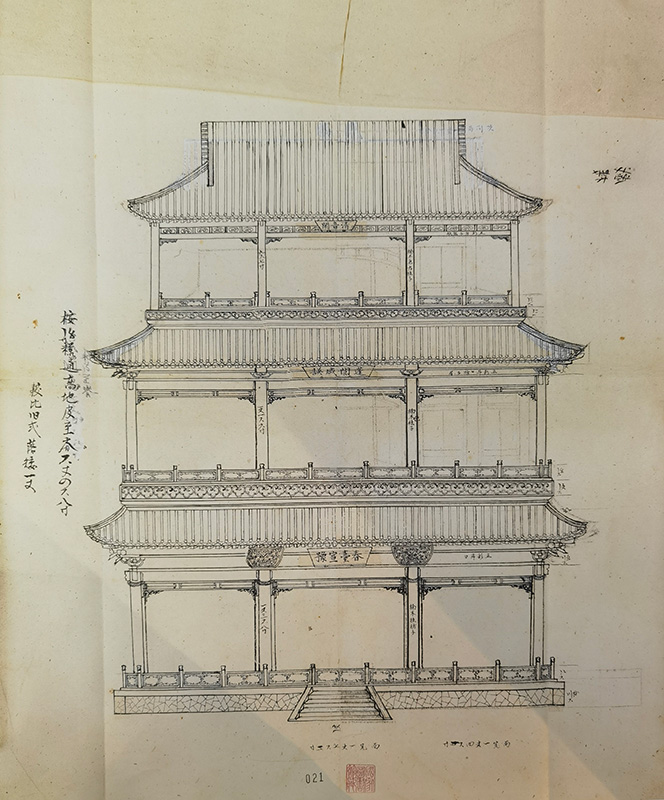

Performance architecture occupied an interesting place in the scope of Chinese building practices. While studies on Chinese architecture usually focus on palace architecture or religious temples, the versatile structures designed for performance have not been thoroughly understood. Although the earliest extant theater structure dates back to the twelfth century, the Qing dynasty was a significant period during which the potential of theater architecture as a building type was greatly expanded, largely due to the importance of performance culture in Qing politics, as introduced above. Imperial rulers challenged the purview of traditional Confucian building practices upheld in previous dynasties and provided a new way to consider the stability of standard building typologies, reimagining mobility and boundaries in the study of Chinese architectural history. Over the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, theater as a regular building type in Beijing was formulated and developed from an occasional architecture into a more stable and permanent category of building. In support of this analysis, I visited the Peking University Library to review collections of primary court drama playscripts and the National Library to examine design manuscripts of palace theaters (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Design manuscripts of three-story palace theater “Pavilion of Clear Sounds,” 46.7 x 38.2 cm. Photocopy.

In the early eighteenth-century Qing dynasty, theater could be defined as an occasional architecture with a pavilion form – a freestanding roofed platform with open sides – where specific forms varied depending on performative occasions. When in use, furniture and theatrical props were constitutive elements of the theater structure rather than the other way around: props and furniture were not restricted or defined by the theater structure independent of these constitutive parts. In other words, this type of architecture was characterized by form being defined by function, or the exterior being defined by the interior.

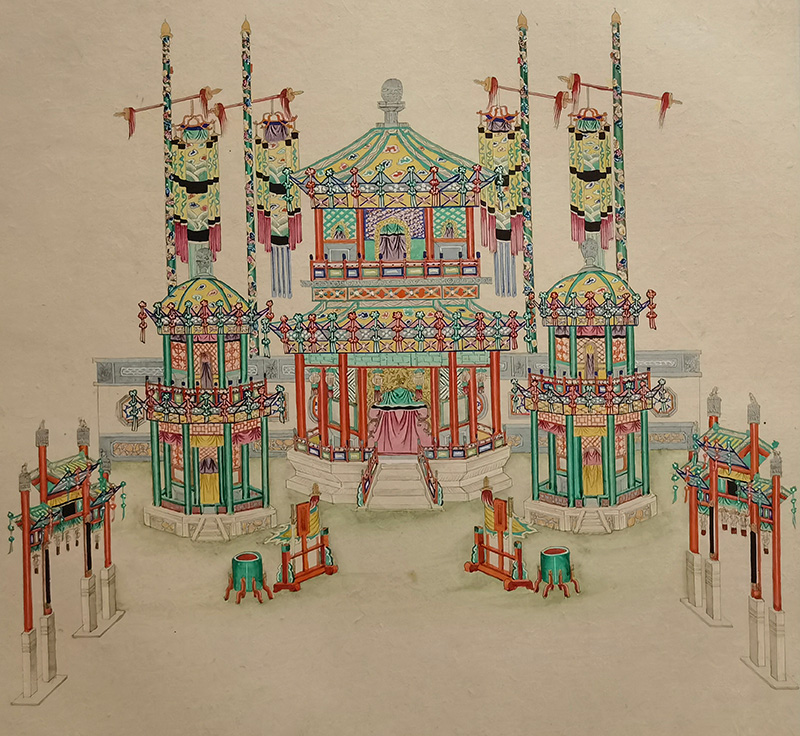

To give an example, in the playscript of the “Precious Raft of Ascending Peace (Shengping baofa 升平宝筏)” collected by the Peking University Library, theater was planned by staging together building elements such as standing screens and curtains on a roofed platform. In addition to these building elements, performers utilized surrounding architecture such as porticoed halls, courtyards, and even the city street or natural landscape in the imperial garden villa as backdrops, thus connecting indoor and outdoor spaces. This made the performance space an irregular open area. In my fieldwork, I made conceptual reconstruction sketches based on textual records. I also visited sites where open-air theatrical performances were being held to get a sense of the actual use of a pavilion stage (Figure 3). The way various building elements were displayed suggests the makeshift nature of theater as Qing architects experimented with the best ways of visual storytelling (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Contemporary music performers (opera singers, music instrument players) utilized a pavilion in Taoran Pavilion Park as the venue for their performance, surrounded by the landscape. Photo taken by the author. 2023.

Figure 4. Painting of Architectures for Celebration of Emperor Kangxi’s Sixtieth Birthday, Qing Dynasty. Photocopy.

All these experiments changed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, gradually formulating a more integral spatial composition as grand multistory theaters emerged as the permanent theater form in the palace (Figure 5). The multiple layers of the stage were accessed through backstage staircases to take full advantage of the building’s layers in staging performers, visuals, and vocals, while the audience was seated around the theater from the outside. This theater structure shows an interest in the monumental effects obtained by careful orchestration to fulfill the creation of tableaux. The idea of a structurally more durable permanent theater became significant in the late nineteenth century when the Qing dynasty engaged in wars with European powers, who destroyed the Qing imperial gardens, including the beloved imperial theaters, during their invasion of Beijing. This warfare encounter imbued a durable grand theater with a spiritual symbol of resilience in its late-nineteenth-century reconstructions.

Figure 5. Three-story theater stage “Pavilion of Pleasant Sounds,” Palace Museum. Photo taken by the author. 2023.

To demonstrates the various types of Qing theaters across the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including occasional theaters and permanent multistory theaters, I compared and contrasted different versions of the same play, “Precious Raft,” and how it was staged for these different settings. This analysis helped me reconstruct the mobile and transformable temporary structures as well as the fixed multistory theaters used for court performances. In the context of the multiethnic Qing empire and its conquests and warfare, the consistent popularity of Qing theater production helps explain how stagecraft diversified the experience of cultural encounters and the expression of political authority. It shows how the statecraft of the gradually expanding Qing empire was materialized through spectacle and stagecraft.

[1] These included population transfers, imperial cults, encyclopedic publishing projects, resource mobilization, and cross-regional trade facilitated by passports. Joanna Waley-Cohen, The Culture of War in China: Empire and the Military under

the Qing Dynasty. 2006; Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper, Empires in World History: Power the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010. 7, 16; Jonathan Schlesinger, “The Qing Invention of Nature: Environment

and Identity in Northeast China and Mongolia, 1750-1850.” Ph. D. diss., Harvard University, 2012, 16.

[2] Joanna Waley-Cohen, “The injection of military and imperial themes into almost every sphere of cultural life.” The Culture of War in China: Empire and the Military under the Qing Dynasty, 2006, xii.

[3] For the list of military activities in the eighteenth century, see Joanna Waley-Cohen, The Culture of War in China: Empire and the Military under the Qing Dynasty, 2006. 23.

[4] Ye Xiaoqing, Ascendent Peace in the Four Sea: Drama and the Qing Imperial Court. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2013; Liana Chen, Staging for the Emperors: A History of Qing Court Theatre, 1683-1923. Amherst: Cambria Press, 2021.

[5] Tong Su, “The Phantom of Empire: Stagecraft in Qing Court Production of Art and Theater 1700-1827.” Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2024.