For many eras, the use of pattern was not controversial, but an integral part of building. Other periods found the use of pattern highly problematic, and either avoided it or used it to take a philosophical position—as an ironic touch or an artistic statement. Patterns can be abstract geometries or representational based on natural forms. Two ways of looking at pattern were central to 19th-century debates. One viewpoint holds that pattern is integral and seems to spring from its materials. In another scenario, it is applied and masks its material host, as applied surface ornamentation. Many 19th- and 20th-century architectural theorists grounded their individual philosophies by considering the differences between ornament and ornamentation.

SAHARA does not have many photographs of textiles, wallpapers, or other materials. When photographing your subjects, consider building material details. As we start the new year, include among your resolutions to make a contribution to SAHARA.

To see more SAHARA content: sahara.artstor.org/#/login

To learn more about contributing, visit: sah.org/sahara

Unknown Creator, Tomb of Akbar, Sikandra, Uttar Pradesh, India, 1605–1614. Photograph by Elisabeth Braun, 2005. Akbar was one of the most important leaders of the Mughal Empire and his architectural works were many. This is a sandstone and marble masonry pattern from his tomb.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Lewis Thomas Laboratory, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, 1986. Photograph by Lauren Soth. Venturi and Scott Brown were two of the most prominent architects associated with postmodernism, and one of their design provocations was their selective use of pattern.

Louis Sullivan, National Farmers’ Bank, Owatonna, Minnesota, 1906. Photograph by Ana Esteban-Maluenda. Throughout Sullivan’s career, he paid careful attention to detailing his projects, often coaxing vegetal forms into beguiling geometries, here made from brick, tile, and terracotta.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois, 1909. Photograph by Ana Esteban-Maluenda. Wright worked for Sullivan, and his attention to decorative detail shows what he learned and how he took American design in new directions. This is stained glass from one of his most famous projects.

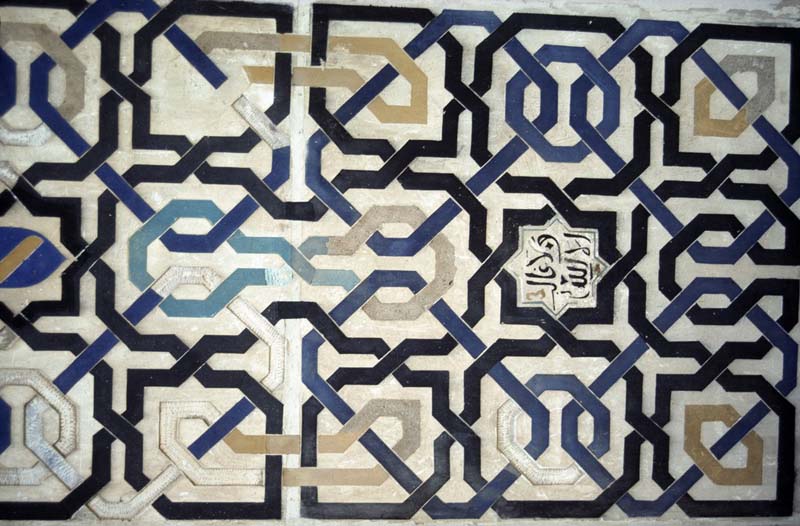

Unknown Creator, Alhambra, Granada, Spain, 1201–1400. Photograph by Reuben Rainey, 1993. Islamic decorations are often augmented with Arabic inscriptions.

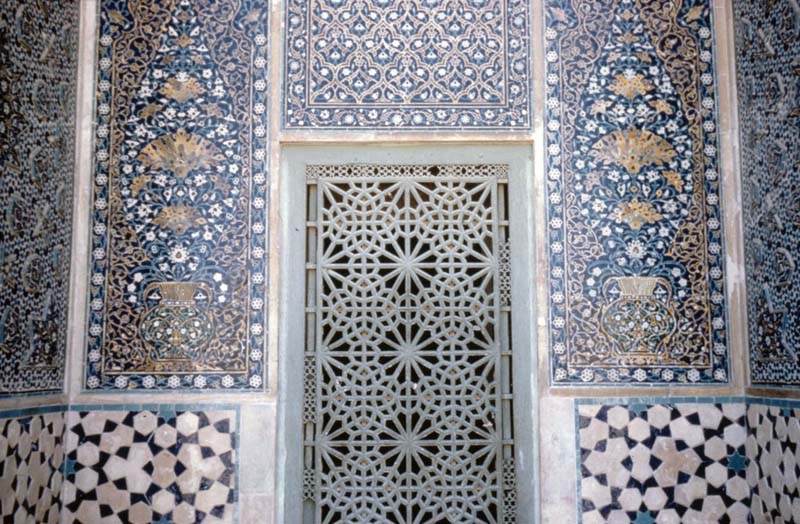

Unknown, Mausoleum of Harun-I-Vilayat, Isfahan, Iran, 1512–1513. Photograph by Marie Ullens de Schooten. The photographer was married to a Belgian diplomat. Her photographs, taken during the period 1951–1972, were given to the Aga Khan Program at Harvard University, an institutional contributor to SAHARA.

Frank Furness, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1871–1876. Photograph by Lauren Soth. In this view, the Academy looks firmly in the Gothic Revival camp, but other parts of the building make clear that Furness drew from a variety of stylistic precedents.

Arata Isozaki, Team Disney Building at Walt Disney World Resort, Orlando, Florida, 1991. Photograph by Richard Longstreth, 1997. Disney also worked with Michael Graves, and the stylistic marriage of the entertainment company with postmodern architects was a match made in heaven. Isozaki’s building was positively received, more so than Graves’ work for the company. Domus wrote that it was “the most architecturally pure of Disney’s buildings” (2019).

Unknown Creator, Baths of Caracalla, Rome, Italy, 216–235 CE. Photograph by Allan T. Kohl, 2001. Wave pattern tricolor mosaic. Even the world of mosaic artists in ancient Rome had a hierarchy. There were accomplished designers, while the Roman version of interns did the prosaic infill work.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Willow Tea Rooms, Buchanan St, Glasgow, Scotland, 1983. Photograph by Dell Upton, 2017. Although built in the 1980s, the project was inspired by Mackintosh’s Ingram Street Tea Rooms.

Hossein Amanati, Azadi Tower, Tehran, Iran, 1971. Photograph by Sahar Hosseini, 2013. This detail is a part of an iconic tower whose structural engineering was done by Ove Arup. The photographer, Hosseini, had an SAH Scott Opler Fellowship.