by

SAHARA Associate Editor Jeannine Keefer | Aug 21, 2023

“Light is not so much something that reveals, as it is itself the revelation.”

James Turrell, Mapping Places, 1987

The presence or absence of light enhances intellectual and spiritual intentions for a space. The designer directs, controls, and alters light on the interior and exterior of a space. As a result, our senses (and bodies) respond to the quality and nature of that light in a space. The built environment as subject of a photograph is revealed by exposure to light, but it captures just one aspect of a space—its appearance, at a particular moment. The viewer experiences nothing of temperature, odor, or the feeling of textures under their fingertips that they would observe if they were physically in a space. But, in the absence of the ability to travel to every structure or space we teach and/or research, the photograph must suffice to convey the intentions of the designer or builder and the space as it is in a moment. For those who photograph the built environment, light can be both friend and foe. When we document spaces for teaching and/or research, we often must make the most of the time we have. Not every photograph is made in the ideal light of the morning. Sometimes we must fight with the harsh light of the afternoon, with deep shadows obscuring details. Other times we must battle the elements, making the most of a day with no sun, or a day of rain or snow. Today, with our digital cameras and cameras in our phones, we can infinitely document buildings and landscapes in these varied conditions.Some images we capture may well be satisfyingly artistic in their own right, layering the space with our own gifts for composition. But, as Mary Woods states in her book, Beyond the Architect’s Eye: Photographs and the American Built Environment, “[…] photography is so embedded in our design culture that its conventions remain transparent at some level […] Their artistry, methods, structures, and consequences remain invisible.” An aggregated collection such as SAHARA has the potential to provide images of a building on its best day, and on its worst, providing a more complete impression of a space than that one perfect elevation or perfectly lit interior. This month’s highlight group is a selection of variations on a theme and compositions featuring a range of lighting situations.

To see more SAHARA content: sahara.artstor.org/#/login

To learn more about contributing, visit: sah.org/publications-and-research/sahara

James Turrell, Dividing the Light, Detail view, 2007, Pomona College, Claremont, CA. Photo: Dell Upton, April 2011

Jørn Utzon, Bagsværd Community Church, Interior, 1974–1976, Bagsværd, Denmark. Photo: Lauren Soth

Jørn Utzon, Bagsværd Community Church, Interior, 1974–1976, Bagsværd, Denmark. Photo: Dennis Whelan, October 2007

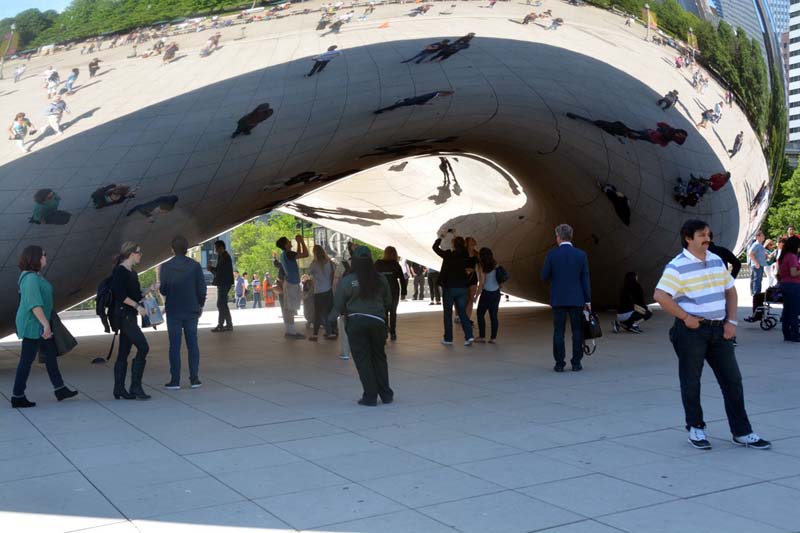

Anish Kapoor, Cloud Gate, 2004–2006, Millennium Park, Chicago, IL. Photo: Dell Upton, June 2015

Anish Kapoor, Cloud Gate, 2004–2006, Millennium Park, Chicago, IL. Photo: Dianne Harris

Gehry Partners, LLP and SOM, Millennium Park, 1999–2004, Chicago, IL. Photo: Dianne Harris

Mayumi Watanabe de Souza Lima, Brasilia Superblock, Brasilia, Brazil. Photo: Victor Prospero

Anthemios and Isidoros, Hagia Sophia, 532–537, Istanbul, Turkey. Photo: Ricardo Agarez, March 2013

Anthemios and Isidoros, Hagia Sophia, 532–537, Istanbul, Turkey. Photo: Ricardo Agarez, March 2013

Temple Complex, 9th–11th Century, Uxmal, Mexico. Photo: William Kessler, 1968

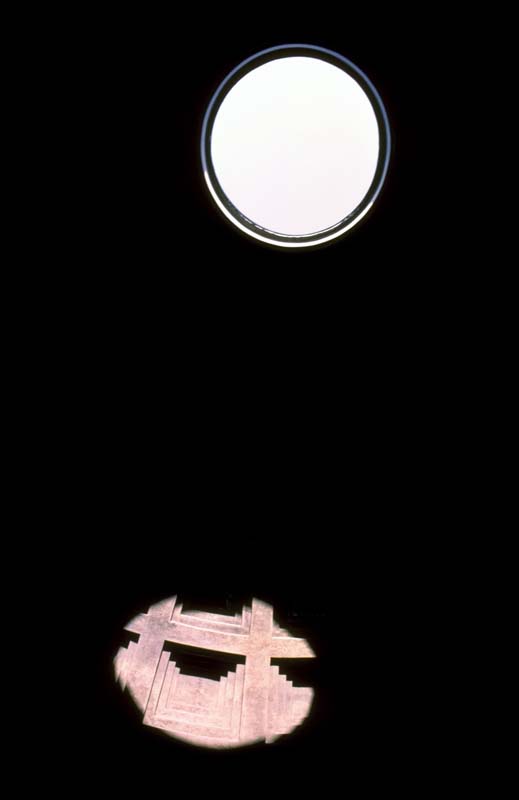

Louis I. Kahn, National Assembly Building, 1959–1982, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Photo: Gerald Moorhead, January 2012

Pantheon, 127 CE, Rome, Italy. Photo: William Kessler, 1965