-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Saint Denis: The Bishop, The Basilica, The Builder

'Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

It is an extremely difficult thing to live for something, let alone die for it. The sum of the last days of Saint Denis presented to us through art will indeed try the very foundation of even the fittest of this age. A singular statement in sculpture eloquently captures the mystery that has made Saint Dionysius (Denis) even more potent in death than alive. Nowhere is the idea behind this potency felt more than in the Basilica Cathedral of Saint Denis—a space that truly embodies a balance between the energies of life and death. Named in honour of the first Bishop of France, the basilica radiates a copious aura of importance and stateliness. As you walk among the remains of early French royals, you cannot help but feel that the dead are alive and sculpturally animated within these walls. Forty-two kings, 32 queens, 63 princes and princesses and 10 great men of the realm lay there, how will one not feel a monarchical musk in the air?

Figure 1: A space for the living and the dead. A view of part of the transept crossing. In the foreground, recumbent funerary sculptures of Pepin le Bref 751-768 AD, Berthe 783 AD, Louis III 879-882 AD and Carloman 882-884 AD.

Figure 2: Sleeping under a heavenly glow. Recumbent pieces of Henri II 1547-59 and Catherine de Medici 1589. Notice the plasticity of the pieces sculpted by Germain Pilon. In the background is Marie de Bourbon Vendome 1538.

Figure 3: Another view of Henri II and Catherine de Medici – Again, Marie de Bourbon Vendome is in the background.

Figure 4: A view looking towards the choir.

Figure 5: Recumbent statue of Phillippe 1235. Here we see a fine example of a funerary cortège carved along the walls of the base marble.

Figure 6: A Royal Necropolis – Here the dead are freely among the living or is it the living that are freely among the dead?

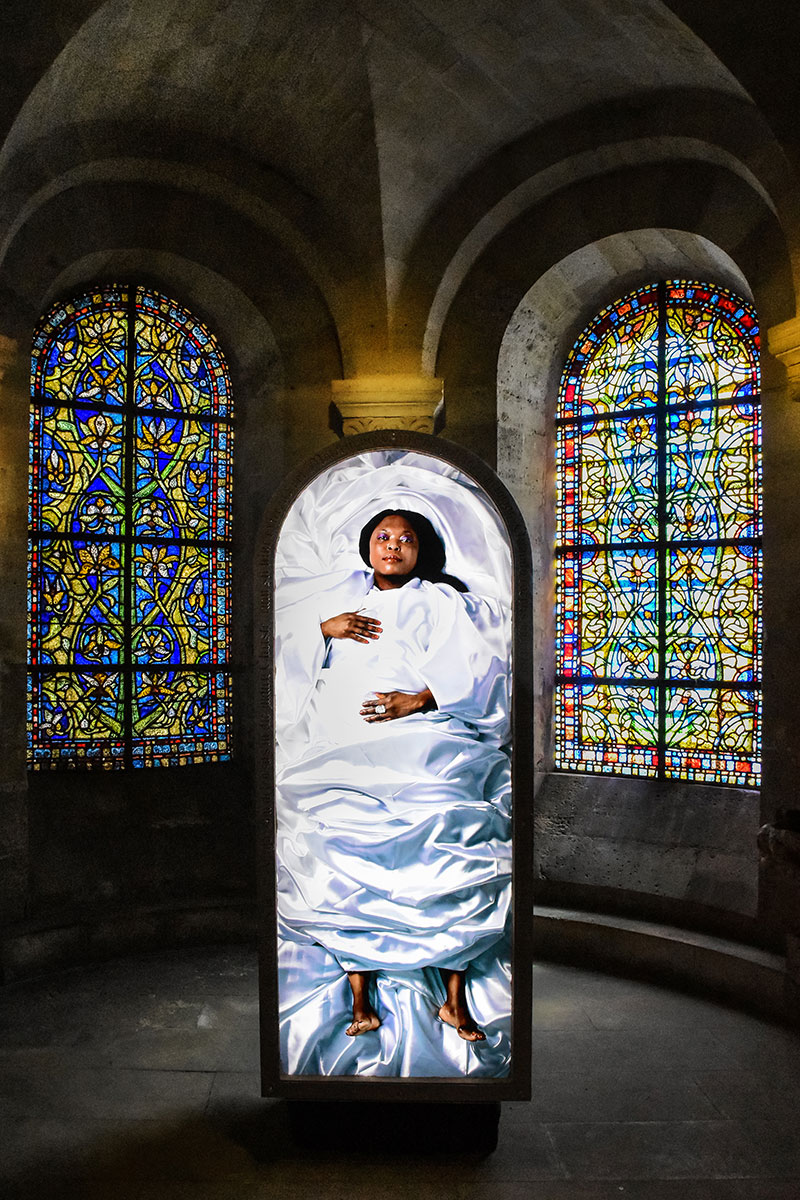

Figure 7: An art installation and exhibition featured in the crypt of the cathedral. Shows a living wrapped in linen as if dead. This creative ensemble further underscores the theme of the living among the dead in the cathedral.

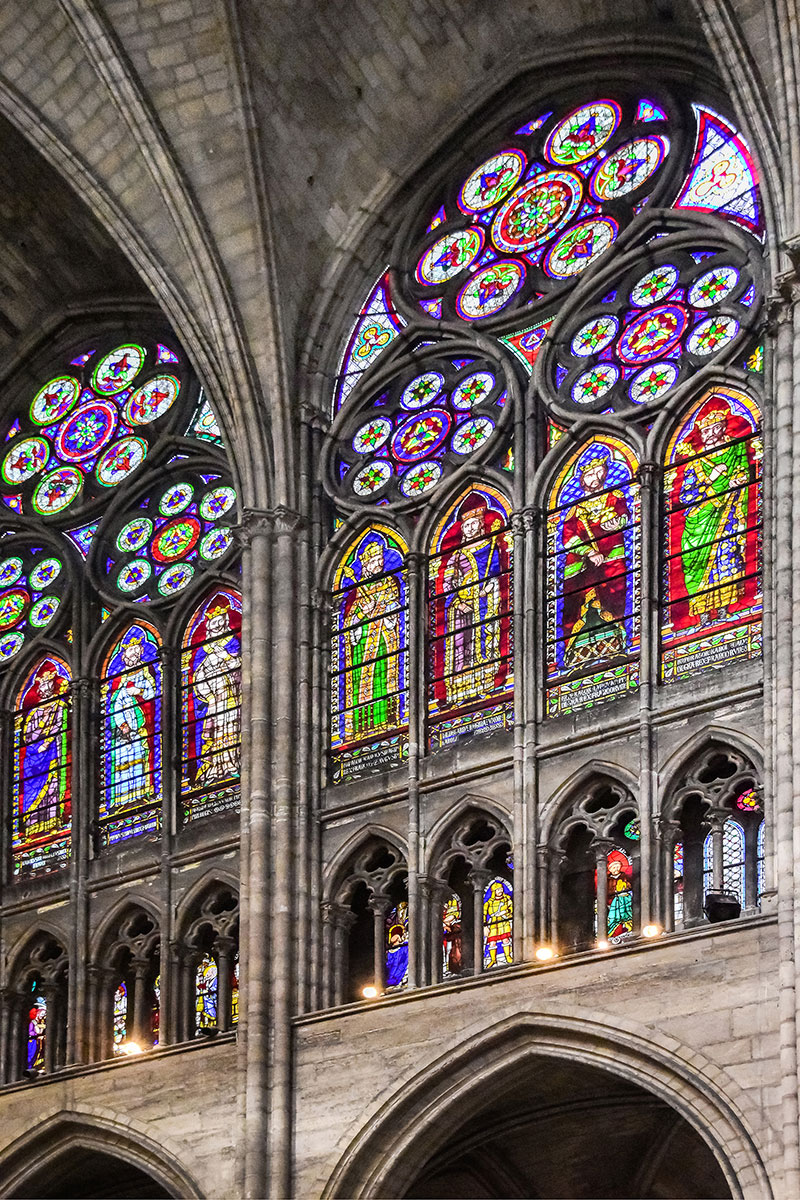

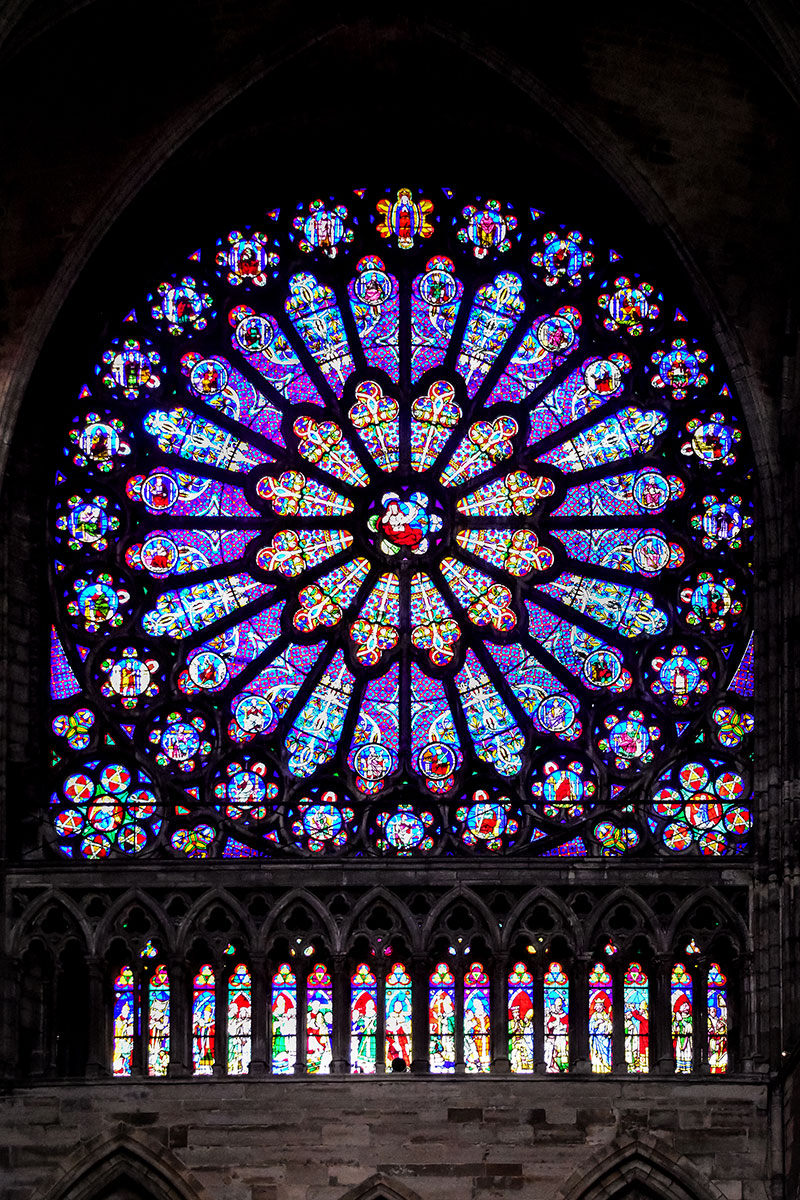

Figure 8: Stained glass in the triforium from the transept crossing. The subjects are past kings and queens of France.

Seeing the funerary effigies lying flawlessly about the interior of the cathedral, one is reminded of the imminent translation that must happen to all. The nature in which the living walk freely among the dead in this basilica also speaks to the oneness in the body of Christ. The Basilica of Saint Denis holds the remains of many great men, but one name that stands out even among kings and princes is the cleric - Saint Denis. An old account states that after being incarcerated for a period as a result of the Decian persecution of the Christians around 250 AD, Bishop Denis eventually was to face a series of torturous acts that would ultimately end in his death by decapitation making him a martyr in the mid-3rd century alongside two others, Eleutherus and Rusticus. But, the real story is to unfold after his beheading. The headless body is recorded to have risen immediately from its knees, picked up the detached head and walked several kilometres. Jacobus de Voragine’s account records that Saint Denis’ mouth continued to preach while he walked with his head in his hands from Montmartre to his burial place, the present basilica of Saint Denis.1 This will make him one of the earliest known cephalophores in church history. Cephalophores are (generally) individuals who were martyred by decapitation and are reported to have exhibited coherent post-decapitation movements and sometimes vocalization often with the severed head in their hands. The phenomenon is portrayed in art as headless figures carrying their own heads in their hands. The word cephalophore is Greek for ‘Head Carrier.’

Figure 9: An iconic image of the martyr Saint Denis as a cephalophore on the Portail de la Vierge of the Notre Dame of Paris. Here, Denis is classically presented with his mitred head in hand and flanked by angels.

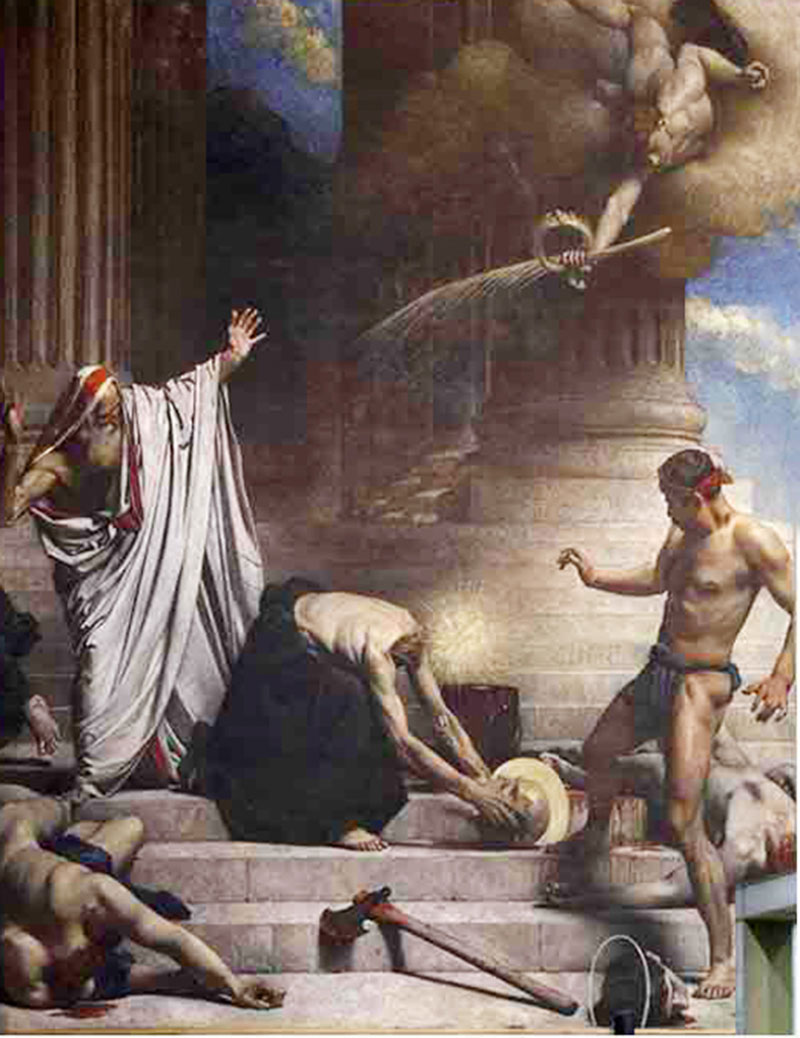

Figure 10: A painting by Léon Bonnat – Le martyre de Saint Denis. Here the artist depicts the decapitation of Saint Denis and his associates Eleutherius and Rusticus. He also captures the moment that makes Saint Denis a cephalophore as he reaches for his head. Source: reliquarian.com

Figure 11: Another artist impression capture the Saint Denis as a cephalophore making the famous journey from Montmartre and preaching a sermon all the way. Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

Figure 12: A wooden sculpture of Saint Denis as a cephalophore in the choir area, Basilica of Saint Denis.

Figure 13: An interesting statue of a bishop caught my attention. Found in the northern aisle, its treatment is such that the head is detached from the body mass but not carried by hands. The head seems to hover over the neck. An angel appears to minister to the bishop through his left ear while covering the right.

A-head with Cephalophores

Saint Denis is probably the most popular but certainly not the only cephalophore. There are several others. In my last article, I featured Saint Nicasius, the 5th-century Bishop of Rheims. Nicasius was recorded to have been reciting Psalm 119 when he was brutally executed alongside two faithful (very much like Saint Denis) Florentius and Jucundus by marauders at the door step of the church. It is said that at the instance when he reached verse 25 of the Psalm ‘my soul clings to the dust,’ his head was severed by the slayer’s cleaver. Picking the detached head up, vocalization continued from the head saying, ‘revive me according to thy word’, needless to say how terrified his killers would have been at such a bizarre sight. Another case is that of Saint Aphrodisius of (Alexandria) Beziers. He was attacked by pagans and beheaded while preaching the gospel. He is recorded to have retrieved his head after decapitation in the presence of his slayers and carried it nearby to a church he had recently concentrated. At this place, the body finally rested. The story of Osyth is similar. She picked up her own head after decapitation and walked a considerable distance with it in her hands to a convent where she finally collapsed and rested. Saint Gemolo is reported to have carried his detached head and mounted a horse. He rode on horseback with his head to meet a Bishop in the nearby mountains before he finally buckled and passed on. Many more cephalophores were recorded. They include Saint Minias, Saint Valerie, Saint Firmin, Saint Maxien, Sibling Saints Felix and Regula, Saint Maurice, Saint Alban, Saint Lambert of Saragosse, Saint Gaines of Nantes, Saint Solange, Saint Winefride and so on. There is in fact quite an exhaustive list of about 134 names in French hagiographic literature.2

The cephalophoric phenomenon is not limited to Roman Christian cultures alone. They have also been recorded in other cultures. A popular example is Chinnamasta, a Hindu goddess. She is always depicted nude, headless and usually standing over copulating couples with her severed head in one hand and a scimitar in another.

In ancient Lagos (Eko), Nigeria, an account of coherent post decapitation locomotion also features in the myths surrounding the earliest settlers of the town. Though not a proper cephalophore in the full sense of it, nonetheless the account records that Ajaye, the wife of Olofin, the earliest settler of Eko (Lagos), was executed by decapitation. The headless body was said to have wandered to and fro the town at night, scaring returning fishermen and passers-by. The act greatly troubled Olofin who had ordered the beheading on account of her leaking family secrets to the spies from Benin kingdom and facilitating his capture by the Oba of Benin. Olofin later sought the help of a sorcerer called Alowore who through magic caused the roaming headless body to drown in the lagoon at a place now called ‘Ibu Ajaye,’ loosely translated as "the deeps of Ajaye."3

Broadly speaking, ending up a martyr was relatively commonplace amongst early Christians. The times were tough for those who professed Christianity and chances were that you ended up headless if you practiced the faith devoutly. Besides decapitation, many saints met their end in the most brutal ways. Saint Erasmus of Formia (ca. 303 AD) was disembowelled, Saint Hippolytus of Rome was pulled apart by horses, Saint John the Apostle was boiled in a large pot of oil, and Saint Bartholomew the Apostle was flayed alive. And should the torturous act not lead to death, it most certainly would have taken a part of their body away. Saint Agatha’s breasts were cut off, Saint Apollonia’s teeth were removed forcefully, and Saint Lucy’s eyes were plucked out.

The iconography of a headless body carrying his or her own head is certainly a curious and powerful image to behold, but what message does this symbolic spectacle pass unto us and how is this relevant to us today? In my view, the visual statement captured by sculpture stands for defiance to death, resilience, and commitment to purpose in the face of challenges. It also stands for the unassailable nature of an idea or belief even in the face of death. The symbol reassures us that even when the worst is upon us, there is yet a mystery that surpasses mundane knowledge which encourages an idea or belief to thrive beyond the limits of the individual. I probably should align more with the submission of J.E. Cerlot in his brilliant introduction in the book The Dictionary of Symbols, where he submits to the argument of Marius Schneider that there is no such thing as ‘ideas or beliefs,’ only ‘ideas and beliefs,’ that is to say that in the one there is always at least something of the other.4 Because of the power and interactivity between the ideas and belief, there is some reason in the notion that while it may be of relative ease to eliminate the carrier of an idea and belief, it is a different thing altogether to supress the message itself—we can quite easily refer to many examples in our collective history. The iconographies of cephalophores thus become a commanding statement or euphemism for continued hope and a reawakening even in the face of death.

Architecture, through the parsing of art, presents itself here as a most viable template for the capture and preservation of the enigmatic story of martyrdom. Art is an effective language that maintains the influence and meaning of the narrative through changing times. The simple iconographic image of Denis as a Cephalophore has brought such immense attention to the idea that the act stands for. We are drawn to the stories today not first by the text in record but by the visual oration that drives us to ask questions and thus in asking we may find answers and in finding we may know. The knowing of a thing then empowers us to live the meaning for which the initial message was intended.

How wonderful it is that the message offered several hundred years ago in sculpture and hosted by architecture still resonates with us today. It is thought provoking to know that the message becomes even more relevant now than ever. The works bring with them such courage to help us face our collective fears and to give us a renewed sense of freedom in the face of the cultural, artistic, and disciplinary massacre we are currently facing through the perpetuation of hatred and fear by extremist ideas.

Figure 14: The arrest and execution of Saint Firmin – A choir screen piece on the south end of the interior of Amiens Cathedral.

Figure 15: A close up of the martyrdom of Saint Firmin.

Figure 16: To the left is Saint Acheul, in the middle is Saint Ache and to the right is an angel. Saints Acheul and Ache are depicted here as cephalophores on the Embrasures of the Northern portal known as the Portal of Saint Firmin the Martyr, at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Amiens.

Figure 17: A closer view of Saint Ache as a cephalophore.

Figure 18: Saint Nicasius, Bishop of Rheims, continued to recite verses from the book of Psalms 119 even after his head fell to the slayer’s cleaver.

Figure 19: Details of the North Façade – the portal of the Saints. The central figure there is Saint Calixtus. To the right of Calixtus' head, just above the lintel, is a detail of the martyrdom of Saint Nicasius.

Figure 20: Close up details of the Martyrdom of Saint Nicasius.

Figure 21: Saint Nicasius depicted as a cephalophore on the Portal of Saints, Rheims Cathedral. Notice angels (interestingly also headless – but not by design, that must be by age) holding a crown of martyrdom over where the Bishop’s head used to be. It is a clear sign of acceptance to higher glory.

Figure 22: The miracle of St Valeria before St Martial, by Giovanni Antonio Galli. She is depicted here as a cephalophore.

Figure 23: Details from the Central Portal of the Western façade of Strasbourg Cathedral. Notice the center roll from bottom upwards – It records the horrific death of several early Christians and Apostles of the faith. Hanging upside down, decapitation, flaying, boiling to death in hot oil, sawing to death and so forth. Those were very harsh times for people of faith.

Figure 24: Just above the lintel, one will notice almost all the featured figures are headless. This is not by design but has happened over time by ageing. It appears that even in sculpture as it is in life, the most vulnerable and likely point of fatality remains the head – body connection. How metaphorical.

Further on the issue of art and depictions, the continued role and relevance of ornamentation as a tapestry of sort through which a legacy of resilience and fortitude is preserved is thus underscored. Ornamentation offers us a type of collective identity that is immune to the trials of changing times and steadfast in its message through simple visual symbolism.

Accordingly, I wish to argue that the plainness or barrenness (permit me this word for emphasis) of an architectural surface does not suggests high beauty, in fact it may very well be a mindless mis-opportunity in design. The opportunity to exercise freedom from repression and honesty of expression, encoded in the language of ornaments, for the consumption of all who will come across it in space and time. Let me add that, like the biblical caution which argues that in a multitude of words, mendacity is not lacking so ornamentation need not be unduly plentiful and meaningless. Instead, it can be brief but heavy with meaning. I have often heard that sometimes, silence speaks louder and clearer than any construction of words man is capable of. On this notion, one is presented with a grave danger, for even with words not properly articulated, a corruption of the original meaning is imminent over time, how much more silence – whatever the original intention, it is far more likely to be misinterpreted. But there is a clarity that comes with visual language which speaks to our inner sensibilities. It remains constant in message and purpose in spite of the years.

The Basilica, the Builder

The Abbey of Saint-Denis-en-France is most famous and glorious among all those of the Kingdom of France. It is foremost among the abbeys of all Gaul and perhaps of all Europe.5 It was Suger however who took this already venerated Benedictine abbey from its late Romanesque character to Gothic starting a new era of the Gothic movement and making himself a key figure in the development of Gothic architecture in France. The basilica that emerged from the tireless work of Suger served as a burial place for French monarchs from the Merovingian era of 447–751 AD through to the Bourbon era up till the early 19th century. Suger chronicled the renovation of the Abbey Church, dating 1137–1144 AD, and the work is said to be one of the most important documents of the Middle Ages on account of the details.6

Abbot Suger, as he was called, was in many ways a builder, statesman, and masterful patron. He dedicated his life to the revitalization of the old abbey and, as his account will show, he turned it into a magnificent piece of art worthy of kings both heavenly and temporal. One will probably best describe his dedication in the words of Daniel Lee, who writes, "In the past Christians gladly served as patrons of church architecture because it proclaimed their faith and affirmed their world views."7 This is in every word true of Suger. The need for Suger to work on the Abbey came as a pragmatic one. By 1122, when Suger became abbot of Saint Denis, the Abbey was already incapable of holding the crowds who came to worship particularly on feast days. The endless crowds came to Saint-Denis to adore the many sacred relics and to participate in spectacular celebrations and processions of all kinds. The congestion in the church often became unbearable; sometimes people were crushed to death.8 To accommodate these crowds and to make the abbey worthy of the position it occupied, Suger decided to enlarge the basilica. With this expansion came a number of innovations that was to set the trend for gothic expressions around all of France. An example is a former oculus on the west façade that served as a precursor of the later popular Rose windows.9

Today, the basilica remains a vivid example of the beginnings of the Gothic movement and a laboratory to study the careful and brilliant transition from late Romanesque to Gothic style. Many of the features we see today are borrowed branches from the Romanesque style but have evolved into a clear Gothic identity. For the whole of France and its Gothic legacy, we have Suger to thank but it would be utterly lopsided if one failed to at least mention the name of another ‘disciple’ who felt called to preserve the Gothic legacy that was falling into ruins—it is Voilett-le-Duc, the one who in the 19th century made extensive renovations and study on the Gothic inheritance of France. It is only on such shoulders a suckling like me stands today. Without their efforts, there would be nothing left to wow about, nothing to build on—certainly nothing as magnificent as I see today. Such visionaries they were. Lastly, while I was in the crypt of the basilica staring into the low lit committal space, it felt as if time walked backwards and the presence of history was almost experiential. Indeed one becomes overwhelmed by the weight of time on one’s shoulders. Time, is truly a heavy mass.

Figure 25: A statue of Abbot Suger at the Cour Napoleon, Louvre. Suger was a brilliant administrator, artist, statesman, and patron of French Gothic architecture and the Basilica of Saint Denis.

Figure 26: Bronze door at the entrance of the Central Portal, Basilica of Saint Denis.

Figure 27: The Choir of the Basilica of Saint Denis. In the foreground are the tombs of the Merovingian Dynasty. There rest (from the nearest) Fredegonde 597, Childebert 511-558 and Clovis I 481-511. The recumbent structures are bathed in a symphony of radiant light from the stained glass above.

Figure 28: Multi-coloured light radiating from the stained glass above ornaments the ambulatory with a vibrant display of colours.

Figure 29: Rose window of the northern arm of the transept.

Figure 30: Altarpiece in the choir of the Basilica of Saint Denis.

Figure 31: The tomb of Blanche (1243) and Jean (1248), children of Saint Louis. Wooden core covered with enamelled copper leaf and cased in glass.

Figure 32: Easy lies this head with the crown. Recumbent statue of Louis VI le Gros.

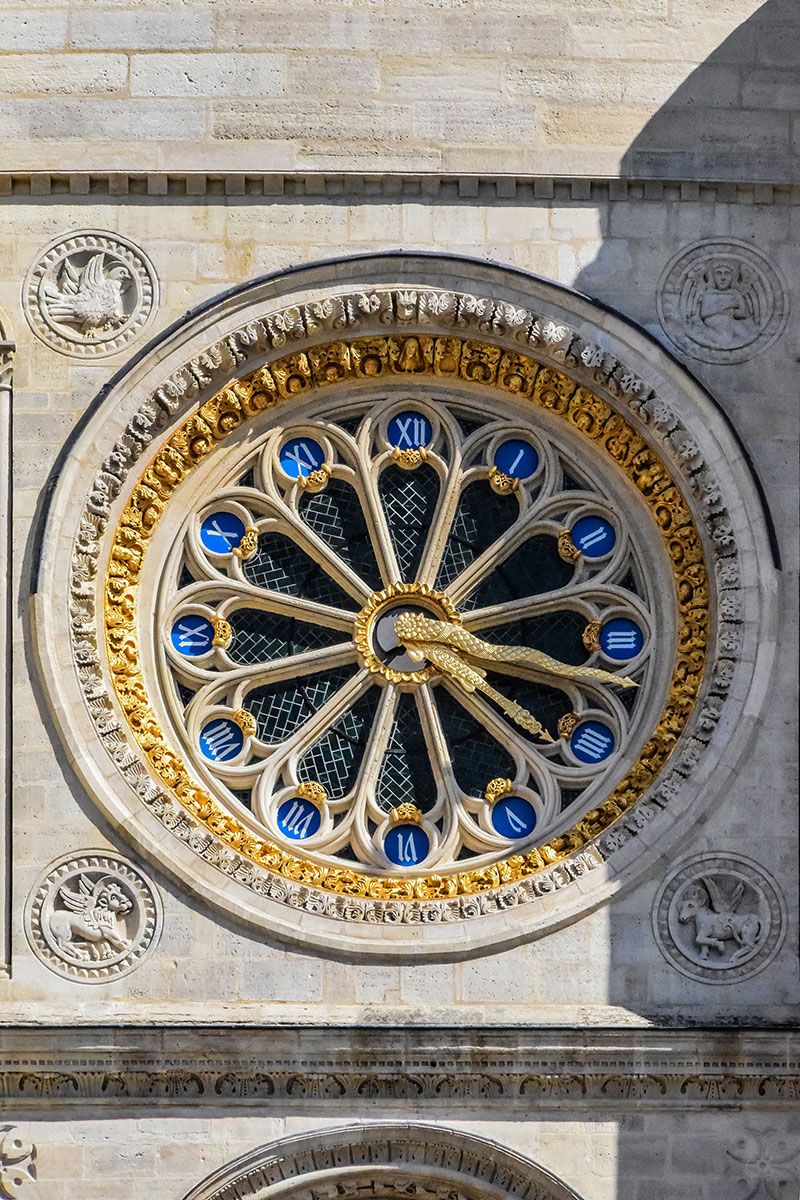

Figure 33: Giant clock with ornate hands incorporated into the reverse space of the rose window.

Figure 34: The Basilica of Saint Denis.

Short Notes on the Cathedrals

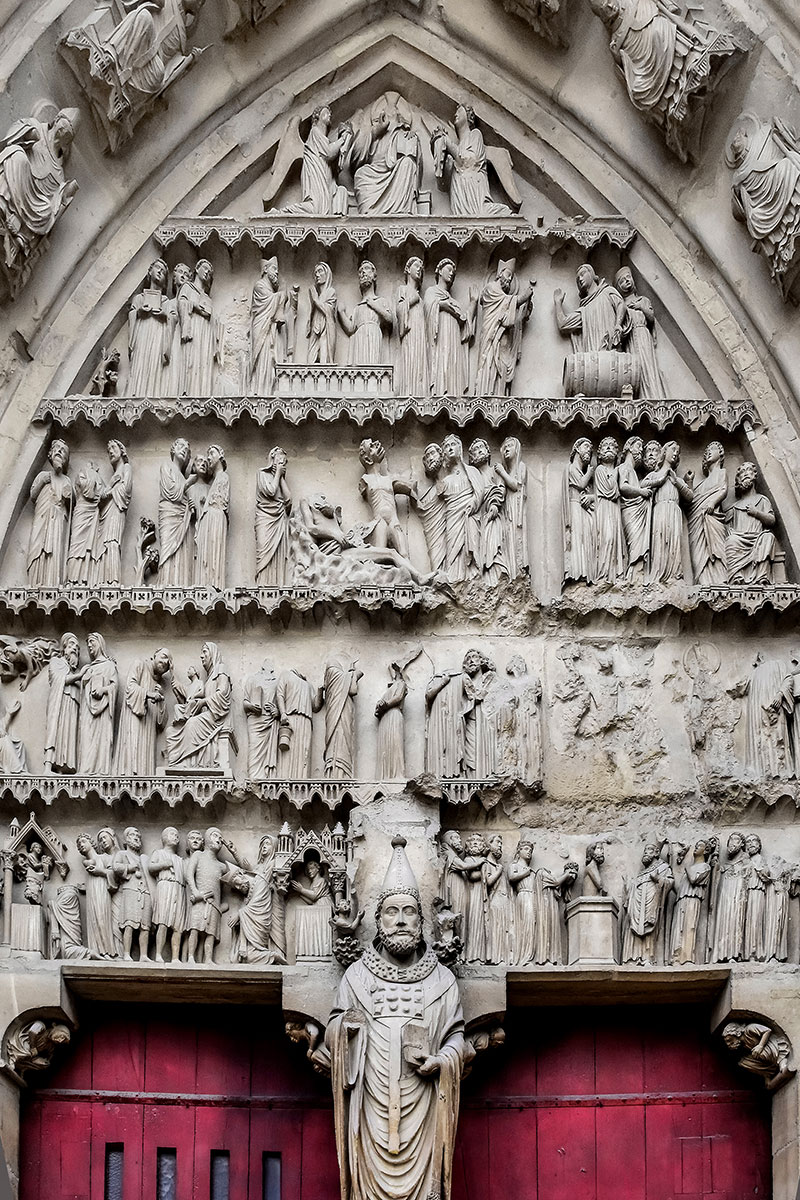

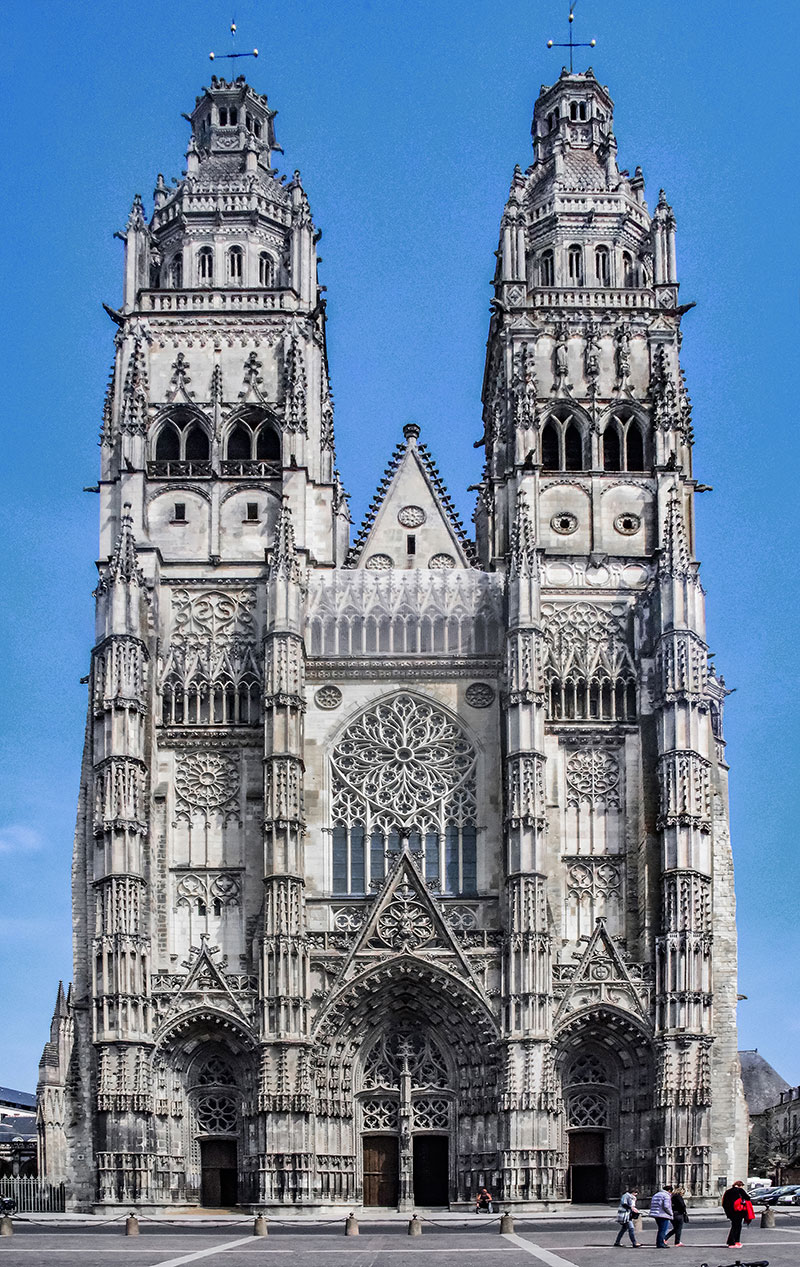

As part of my tour, I visited the Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres and Saint Gatien's Cathedral, Tours. At both sites, as it was now my practice, I sat in front of the building facing the western portals and stared at the mastery of men before us. My sitting, my stare, my wonder, were long and honest. They tell you that when you stare at a thing in silence for a protracted period of time, your mind eventually takes the better part of you. At Tours, I may have experienced this. I sat dead opposite the building given to no distractions whatsoever except for the time I took the photograph of the heavily detailed giant. (See Fig 35.) After a long stare, the building almost became transformed before my very eyes. It seem to take an appearance of an African masquerade in form, texture, and character. The openings on the upper levels of both the northern and southern towers did look like eyes of some sort. You must forgive me; this is clearly the African in me juxtaposing materiality and imagery—such visual concoction. It was an amusing experience though, one that will linger. The experience at Chartres was mellower, though I must confess it was no different from that of Notre Dame in Paris and Amiens—total awe. Chartres is famed to be a key monument in the emergence of the Gothic style sculpture. The poetic works at the cathedral’s western portal flagrantly affirm this. It’s very detailed early works remain some of the finest examples of Gothic oration in all of France. William Wixom in his article Medieval Sculpture confirms the centrality and reputation of Chartres in the scheme of early Gothic portfolio when he speaks of the high quality of Chartres’ thirteenth-century choir stone screens.10 Some notable works on the cathedral include The Ascension, a three tiered piece which captures the apostles in the lower register, Christ the King surrounded by the four beasts, and the twenty-four Elders of the Apocalypse in the center and the standing apostles on the lintel.

Figure 35: Western Façade of the Saint Gatien Cathedral, Tours.

Figure 36: The Northern, Central and Southern Portals of Saint Gatien Cathedral, Tours.

Figure 37: Detail of the Central Portal of Saint Gatien Cathedral

Figure 38: Christ the King as center piece on pediment of the central portal.

Figure 39: Casing of the great organ in the southern transept of Saint Gatien Cathedral. The casing dates back to 16th century.

Figure 40: Western façade of the Chartres Cathedral

Figure 41: Detail of a sculptural piece on the Chartres Cathedral. The Cathedrals presents some of the finest samples of early Gothic sculpture in France.

Figure 42: The angel with the sundial perched at the southern corner at Chartres Cathedral.

Figure 43: Jamb sculptures on the Chartres Cathedral depicting Old Testament kings and characters.

Figure 44: Jamb statues of the western façade at Chartres Cathedral.

Figure 45: The Choir of Chartres Cathedral and in the centre we see L’ Assomption – the beautiful marble piece at the altar.

Figure 46: Heavily ornate point-lace style choir screen, Chartres Cathedral

Figure 47: Part of the labyrinth in the nave of the Chartres Cathedral.

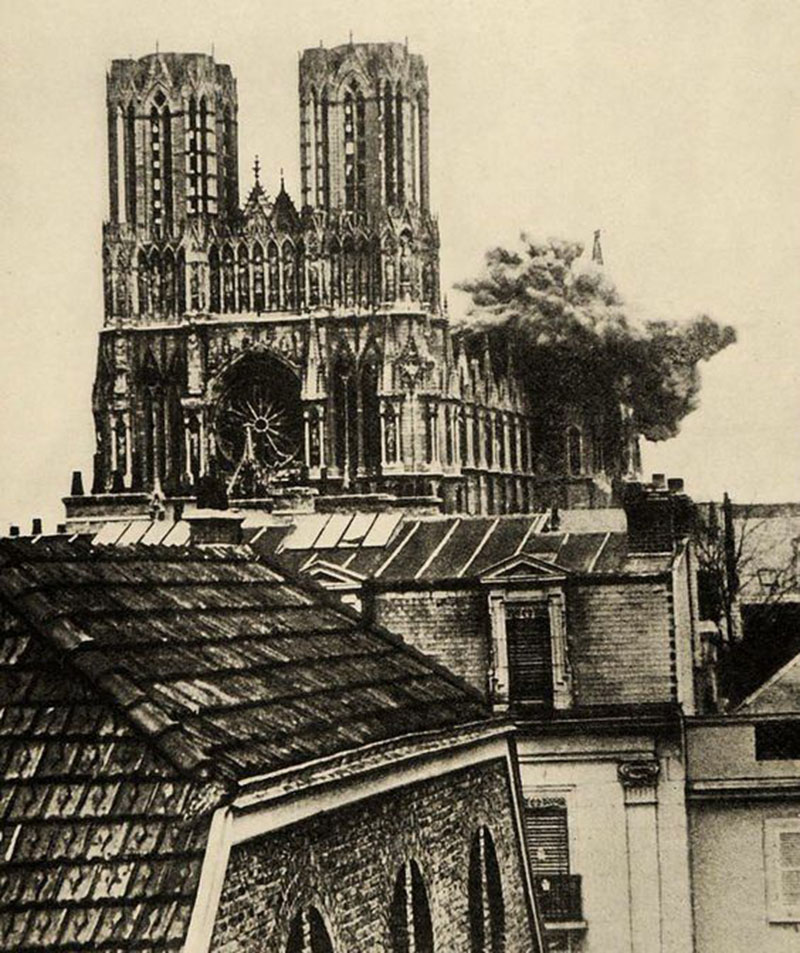

I will at this point bid farewell to France. As I ready myself for the next destination, I am reminded of the words of a friend I met here: He said Paris grows on you. This is true in very many ways—though I might rephrase and say it is all of France that grows on you. A land of many Notre Dames. A place with a rich urban fabric and a melting pot of many shades of beauty. It is very easy to find your place here. Sitting in the very presence of history right before the magnificence of Gothic cathedrals, I could easily find my place. Staring for minutes at the sculptural ornamentation on the western portals gave me a type of warmth that comforts you as you journey back in time to when the masons were on scaffolds trying to fit things to place. It is the kind of feeling that any historian will understand. I can see age on the skin of the architecture but it is the type that glimmers with pride. Like mankind, these cathedrals have gone through an unimaginably rough history but it is uplifting to see that through it all, they have maintained their dignity and a freedom to remain true to self in spite of the changing times. These lessons I will take away from here. At a most practical cost, preserve your freedom and be true to who you are in spite of the pressure of fear and extremism. Value your heritage and preserve it. Invest time and mind in it and never falter in your responsibility to present and pass it on to coming generations. For it is in this, we can hope that a reference to our humanity and identity will remain unspoiled. These things I will not forget.

Figure 48: A difficult past: Rheims Cathedral, being bombarded by the Germans during World War I. Source: Pinterest.com

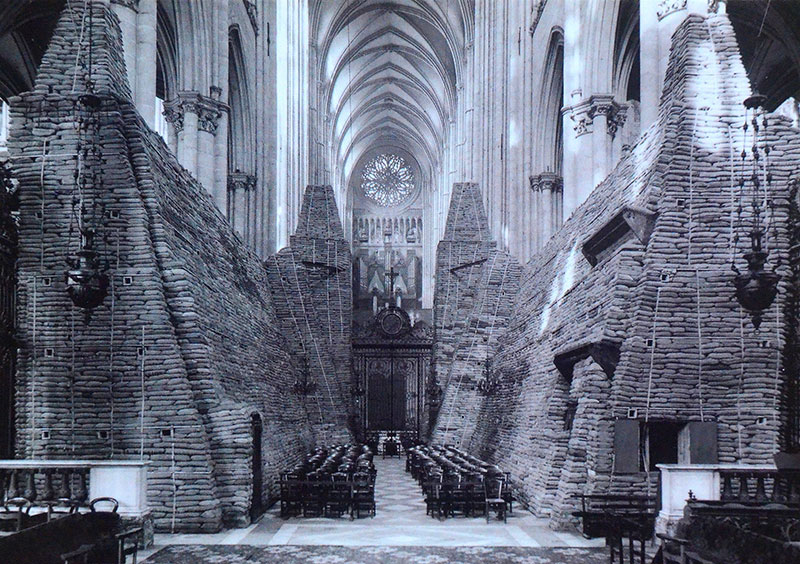

Figure 49: A difficult past - the interior of the Notre Dame Cathedral of Amiens during the war. Authorities take precautions to protect the church with sand bags. This will help give the tall structure stability in the event of shelling. Photo: Centre des Monuments Nationaux, 1940

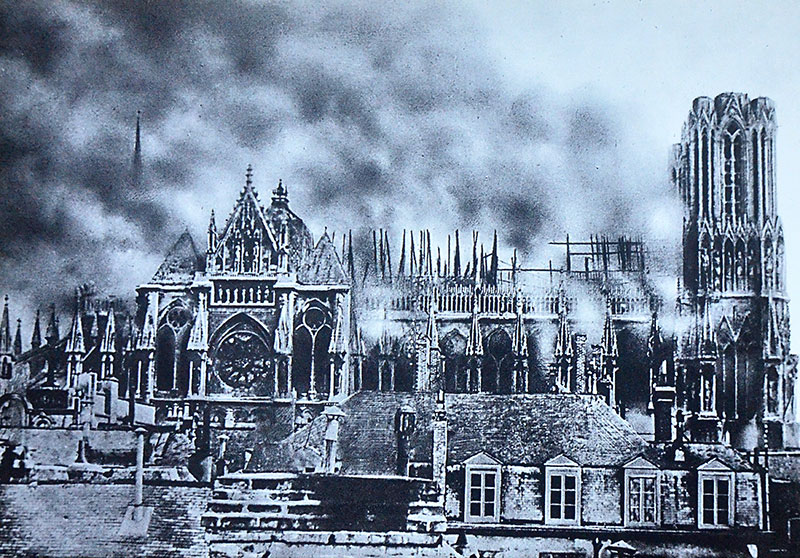

Figure 50: A difficult past – Rheims Cathedral in Ruins! Engulfed by fire on 19th September 1914. Photo: Centre des Monuments Nationaux.

Figure 51: France – A country of many Notre Dames. ‘Notre Dame de - ’ as the cathedrals are called, the iconography of the Holy Mother carrying a baby (Jesus) and sometimes depicted with a flower in one hand is very apparent in all the cathedrals. The statue of Notre Dame (Our Lady) as seen in (from left to right) Strasbourg Cathedral, Rheims Cathedral, Notre Dame of Paris, also Notre Dame of Paris and Amiens Cathedral.

Figure 52: The Love locks of Paris. Thousands of padlocks cling to this bridge and the keys to the locks are resting on the bed of the Seine River below. The locks are a symbol of unending love to many visitors. City council however do not share this fairy tale love story – they blame the padlocks for heritage degradation and a serious risk to the safety of visitors as the collective weight of the locks threatens to tear portions of the balustrade off and may crash in the heavily navigated river below. The Seine River is already facing some environmental problems as a result of the degradation of thousands of metal keys at the bottom of the river. In the background is the Louvre Museum.

Figure 53: Rui loves Ana! Close up shot of love locks. Paris city council are taking down the padlocks and making them into art installations that will be auctioned to raise money for refugee aids.

Figure 54: The Eiffel Tower, a notable landmark in Paris. Just couldn’t resist adding this.

1 Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend. Reading on the Saints, ed., W.G. Ryan, 2 vols. (Princeton N.J., 1993), 236–241.

2 Émile Nourry, Les saints céphalophores. Étude de folklore hagiographique, Revue de l’Histoire des Religions (Paris: E. Leroux, 1929), 158-231. (Quoted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cephalophore)

4 Eduado J. Cirlot, introduction to A Dictionary of Symbols, trans., Jack Sage (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971), xi.

5 Vera Ostoia, “A Statue from Saint Denis,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Vol. 13, No. 10 (1955): 298.

6 “Athena Review,” accessed May 19, 2017, (2005) Architecture and Sculpture at the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis. http://www.athenapub.com/14saint-denis.htm

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top