-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Museums In and Out of Doors: Curating Art, History, and Nature on the Island

All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

As I approach my sixth week of travels, I am enjoying a very welcome feeling of familiarity with Reykjavík and its environs. I have a favorite coffee shop, a preferred place to watch the late night sunsets that never disappoint, and the capital city’s parks are now animated with locals and visitors due to the recent ‘heat wave’. The crest of summer also welcomes a host of pop-up events around the city, ranging from a massive slip-n-slide on the steep shopping street of Laugavegur to a beer garden in the Old Town complete with transported turf to line the cobblestone streets. The days, however, are rapidly growing shorter: instead of the midnight sunset and 2 a.m. sunrise of the summer solstice, daylight lasts from about 4:30 a.m. until 10:30 p.m. and that light grows shorter by about ten minutes each day. Although the sunny hours are slipping away, studies from the Icelandic Board of Tourism prove that visitor numbers are nearing their peak for the year, at a little over half a million.1

Figure 1. Artificial light illuminating the buildings of Reykjavík Old Town in summertime.

Since 2013, tourism has been the main stream of revenue for the island. The majority of tourists state that ‘nature exploration’ is the main goal of their journey and in anticipation of the demands imposed by high visitor numbers to the islands, the Tourist Site Protection Fund was established in 2011.2 The Fund is currently working with 450 sites around the island, but their impacts have been limited due to the requirement that localities provide 50% of the funding for projects. As Iceland continues to promote ecotourism, local authorities are rushing to construct barriers for protecting tourists and natural resources alike: waterfalls, cliffs, and thermal fields pose dangers to curious visitors who wander from prescribed routes, site erosion runs rampant, and ecologists are carefully monitoring water and soil quality.

Figure 2. A sign at the Seltún thermal fields.

Through the Fund, officials hope to construct pathways, viewing platforms, and accessible routes that can be easily placed, and even removed, without large impacts on the natural sites.3 These interventions must sustain themselves with minimal maintenance, despite harsh climatic conditions, since the staff members of various parks and natural sites are already overtaxed. To fund so many built interventions, the government is currently evaluating the concept of a ‘nature pass’: a fee structure for all natural sites that would help support both necessary building initiatives and provide adequate staff.

Aerial view of the harbor skyline.

Curiously, as the island tries to inaugurate a massive do-no-harm building program for ecotourism, bringing essential way finding and landscape architecture interventions to frequently traversed sites, the island is doing fairly little to promote its architectural heritage or museums. These sites seem to fall to a second tier, at least from an advertising perspective, when compared to the Golden Circle, glacier walks, or even visits to the Blue Lagoon. Although one can find myriad walking tours around the capital, and many for free, the built environment is strangely absent from the offerings. There are tours that celebrate Reykjavík as a UNESCO City of Literature, ‘walking the crash’ from the banking fallout of 2008, pub crawls, culinary tours, and even an exploration of street art from the grassroots group I Heart Reykjavík, but there is not a tour primarily dedicated to the architecture and urban development of the city. In hopes of highlighting a few sites that can escape the typical visitor, this post will focus on some of the architectural gems of Iceland’s southwest and museums in the capital that provide an interesting glimpse into the island’s history through unique means of historical interpretation. Moving forward in partnership with Iceland’s new tourist initiatives, it will be critical that these architectural sites also receive the funding and attention needed to ensure their preservation.

Figure 3. A photomontage by the author of the Héraðsskólinn girls’ school, now a hostel, in Laugarvatn that combines photographs from 1936 and 2016. State architect Guðjón Samúelsson designed the school in 1928 and the roofline was intended to reference the region’s traditional domestic architecture: gabled turf farmhouses from the 18th and 19th centuries.4

Figures 4–5. The Skálholt historical site, featuring a cathedral from the 1950s atop the ruins of a 12th-century monastery and a reconstructed turf-covered chapel.

Figure 6. A restored portion of the tunnel that once connected the medieval monastery to the adjacent school.

Figure 6. A restored portion of the tunnel that once connected the medieval monastery to the adjacent school.

Figure 7. A view of the nave of Skálholt church (1956-1963), with stained glass windows by Gerður Helgadóttir.

As explained by architectural historian Pétur H. Ármannsson in an essay entitled “The Mountains are Their Castles,” there are several reasons for the large gap of preserved structures within Iceland’s built record.5 The volcanic soil and porous lava rocks require alternative approaches to traditional stone building techniques and the production of brick is nearly impossible. Prior to settlement, approximately 25% of Iceland was forested but it is estimated that by the 12th century less than 2% of the island was wooded, putting a severe restriction on the use of wood for domestic or civic architecture. Complicating factors were the harsh climate as well as the tradition of rotating tenant farming in the 18th and 19th centuries: workers needed dwellings that could be constructed quickly with local materials and easily maintained in the harsh weather. Therefore, Icelanders turned to dense, turf-covered structures and used stretched Skate fish as translucent coverings for apertures in the roof. As buildings that literally combine the built and natural environments, Ármannsson recognizes these vernacular constructions as Iceland’s most important contribution to architectural history.6 However, with the exception of two living history museums, these structures are not part of the main cultural narrative presented to visitors to the island and it is difficult to trace Iceland’s architectural history within the nation’s established museums. Nonetheless, visitors who are willing to do some independent investigation can assemble the puzzle of Iceland’s architectural heritage by visiting several of the nation’s museums located both in and out of doors.

Of the five sites that comprise the Reykjavík City Museum [the Árbær Open Air Museum, The Settlement Exhibition, the Reykjavík Maritime Museum, the Reykjavík Museum of Photography, and Viðey Island], the majority feature interesting architecture but the interpretation of the sites focuses on other aspects of history.

Figure 8. A photograph from the Vikín Maritime Museum, illustrating Reykjavík’s harbor in 1910.

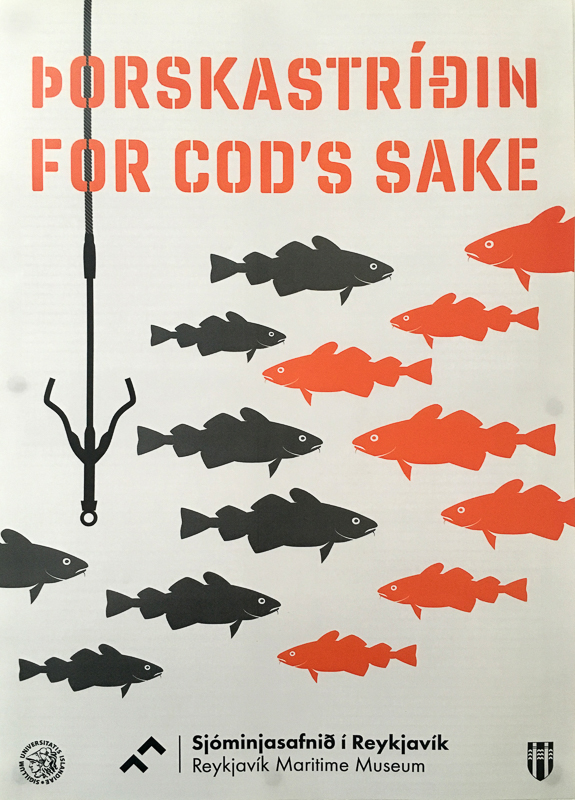

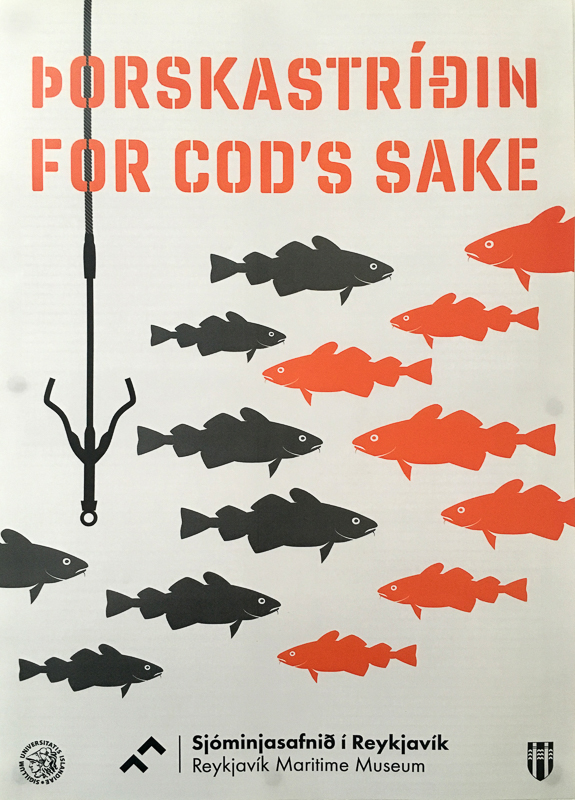

Figure 9. One of the permanent exhibitions in the museum focuses on the Cod Wars that occurred from the late 1950s to early 1970s as Iceland expanded its claim on the fishing territory around the island.

For example, the Vikín Maritime Museum (established 2005) is a recent adaptive reuse project that transformed a midcentury fish freezing plant into a site for interpreting the history of the harbor (figures 8–9). In hopes of creating a new path for understanding the architectural history of Iceland, this post will examine two sites within the Reykjavík City Museum, the Settlement Exhibition and Viðey Island, alongside several other natural site and cultural institutions.

Figure 10. The unassuming entryway of the Settlement Exhibition does little to advertise the rich collections.

Figures 11–13. The ruins of a Viking longhouse, preserved within the subterranean Settlement Exhibition, exist a story beneath one of the Old Town’s main corners.

In addition to the unparalleled example of early architecture and vitrines around the perimeter of the room that hold relics and fragments discovered at the site, including bones of the now-extinct auk, the Settlement Exhibition is also home to some of the subtlest and most effective interactive installations I have ever seen within an interpretive exhibit design. The elliptical, subterranean exhibit surrounds the on-going archaeological excavations and the dim lighting provides ideal conditions for the backlit display boards. Here, ghostly silhouettes that hunt, fish, farm, and build enliven vibrantly colored representations of Reykjavík in the Viking era. The exhibits truly bring to life the 'smoky bay' and showcase how the city derived its name from steam plumes of nearby thermal springs. A touchscreen table allows visitors to explore the ongoing excavations at the longhouse while another screening room provides information on the materials and construction processes used by Viking builders. The museum is also home to manuscripts of the Sage Age, an era of the 12th when Icelandic writers recorded the oral histories of settlement, battles, and dramas of the initial settlement period from 870 to 930.

Animation of an early Icelandic inhabitant hunting a great auk now extinct, within the exhibition.

Figures 14–16. The illuminated and interactive displays of the Settlement Exhibition are put in stark contrast with the dimly lit ruins and utilitarian concrete posts and beams that support the subterranean space.

Figure 17. The stairway leading visitors back to the present-day level of Reykjavík.

Although entirely fascinating and perhaps one of the best exhibits for learning about how and why Reykjavík was settled, the subterranean museum receives fewer visitors than other sites. Like the Roman amphitheater discovered beneath the Guildhall in London or the Crypte archéologique du Parvis Notre-Dame, the Settlement Exhibition literally falls below the radar of many visitors but numbers have been bolstered by its inclusion on the Reykjavík Welcome Card, a tourist pass for access to various transit options and cultural sites.

The key site one would expect to find information on the built environment is the Þjóðminjasafn Íslands, the National Museum of Iceland. Although there are a handful of exhibits on traditional building techniques and a reconstruction of a baðstofa (figures 18–19), a typical one-room residence for much of Iceland’s rural population in the 19th century, the museum operates without an architectural curator. This is more incredible considering the museum serves as the steward for forty historic structures around the island.

Figure 18. The interior of the baðstofa illustrates the simple furnishings and build-in beds that were common in these dwellings. The single volume form helped concentrate heat during the colder temperatures of Iceland’s medieval period. Photograph captured in the National Museum of Iceland.

Figure 19. Various domestic accouterments from the late 18th and early 19th centuries, ranging from iron house keys decorative weather vanes bearing the family name of the occupants and date of construction. Photograph captured in the National Museum of Iceland.

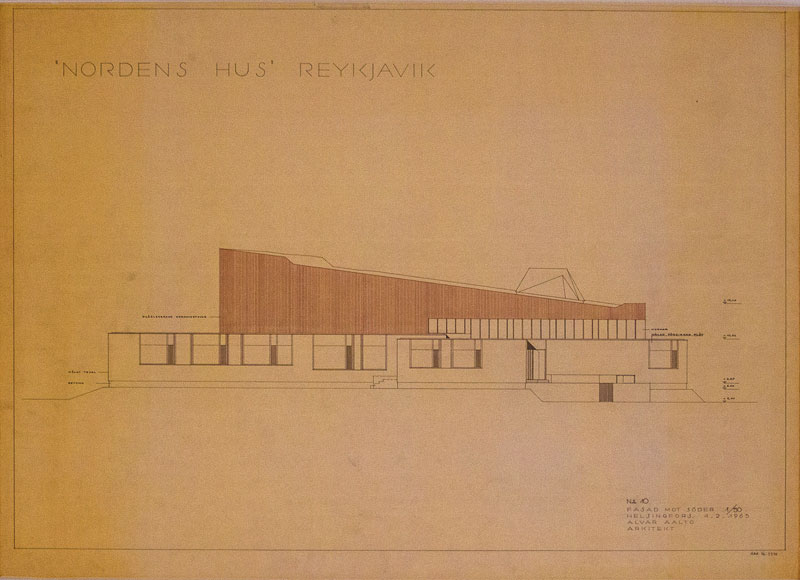

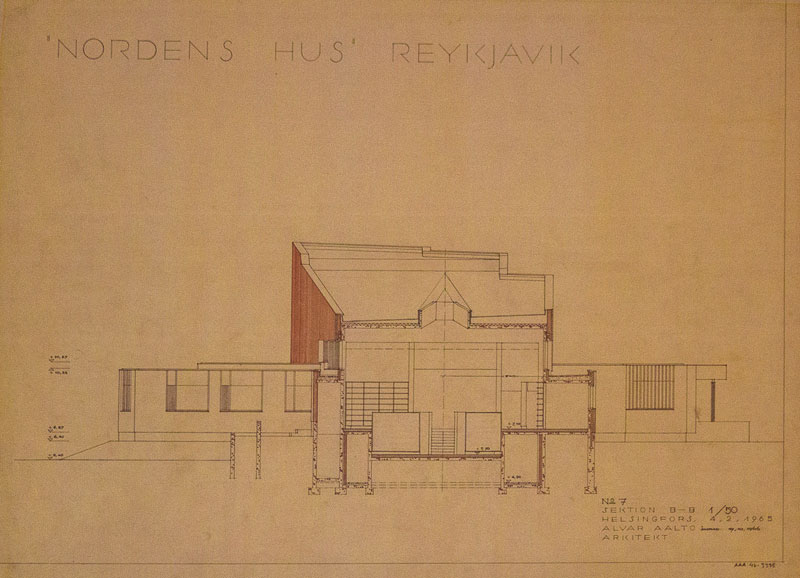

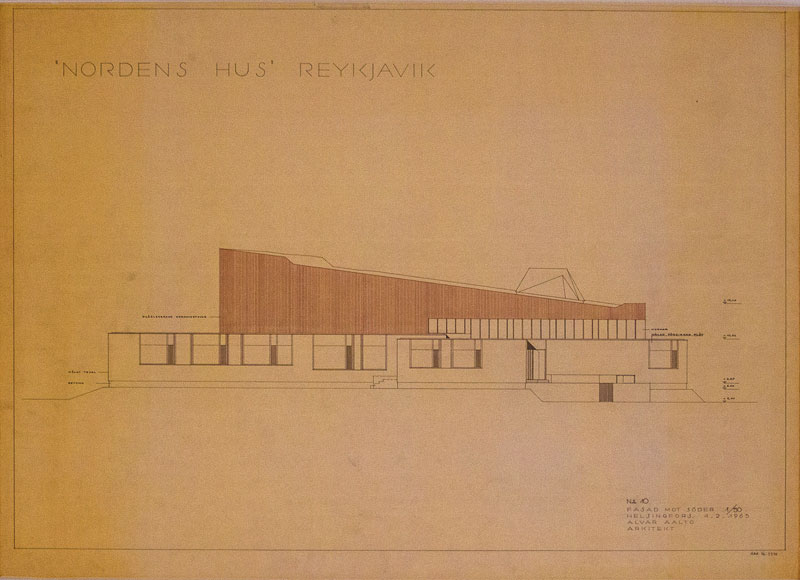

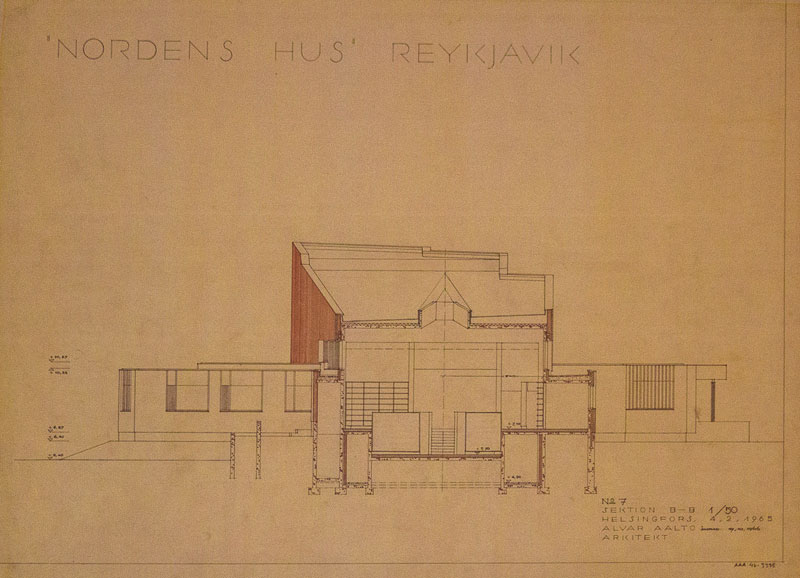

Established in 1863, the National Museum of Iceland was originally housed in a series of public buildings in the Old Town. In 1945, State Architect Guðmundsson was charged with the design of a purpose-built museum, just outside of the city center along the Hringbraut ring road. Resembling a Werkbund factory more than a museum, the building features a series of chronological exhibitions rooms across three floors. With only a small section of one floor dedicated to the architecture of the island, visitors have to search a bit harder to understand the issues that facilitated transitions in construction and aesthetic principles. Leaving the museum, it is not clear how Iceland’s built environment evolved from turf-covered vernacular structures to neoclassical civic building to a capital city dominated by concrete. Local masterworks are unexplored and one of Reykjavík’s most prized architectural gems, just south of the National Museum amid the monumental early 20th-century institution structures of the University of Iceland, is not mentioned in the National Museum. This means that without some careful, prior research, architectural enthusiasts could miss the Nordic House that was designed by Alvar Aalto between 1963 and 1968 (figures20–29). It is home to a 30,000 volume library, small performance hall, and café for cultivating exchange between Iceland and other Scandinavian countries. Like the majority of his other projects, Aalto designed the hardware, furnishings, and lamps for the building. The unstained wood and the use of white paint throughout the building provide a neutral backdrop that makes natural light the main decorative feature of the building. The building’s exterior features the only bit of bold color: ceramic blue tiles line a portion of the roof and the sinuous line mimics the mountain range in the distance.

Figure 20–21. Views of and from the Nordic House emphasize the capital city’s dramatic landscape.

Figure 20–21. Original architectural drawings of the project hang within the building’s corridor.

Figure 24–29. Views of the interior of the Nordic House reveal several pieces of furniture and light fixtures designed by the architect.

It is in Aalto’s library that visitors can find some of the best resources for exploring Iceland’s architecture. Thankfully, the recent production of small guides and resource books help fill in the gaps about the nation’s architectural history. An architectural series by Björn Björnsson explores a few building types and some newly placed and state-sponsored signage helps tell the story of sites such as the Government House or Parliament.7 But to understand the transition from buildings made of turf to those constructed of stone, visitors have to venture to Viðey iIsland in Kollfjödur. The round-trip ferry ride to Viðey is part of the Reykjavík City Card and this tiny island, just a short ride from Reykjavik's old harbor, boasts a rich history (figure 30).

Figure 30. The view of Viðey Island from the Reykjavík harbor places the nation’s first stone structures within an impressive nature backdrop.

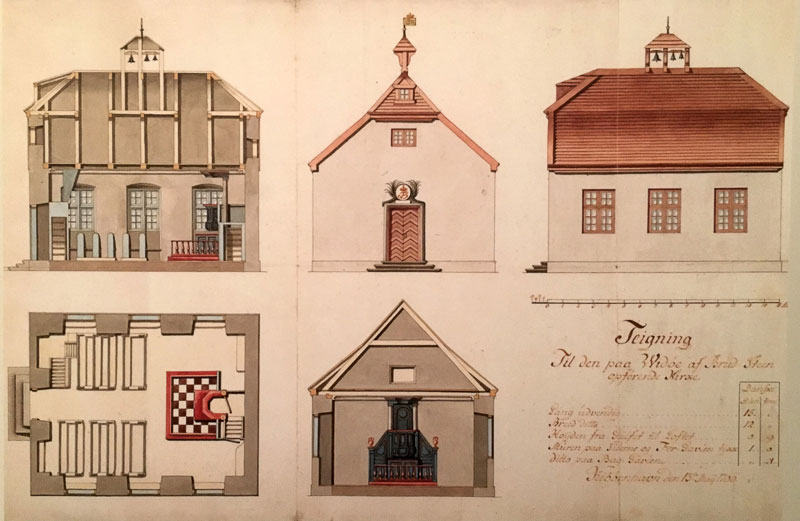

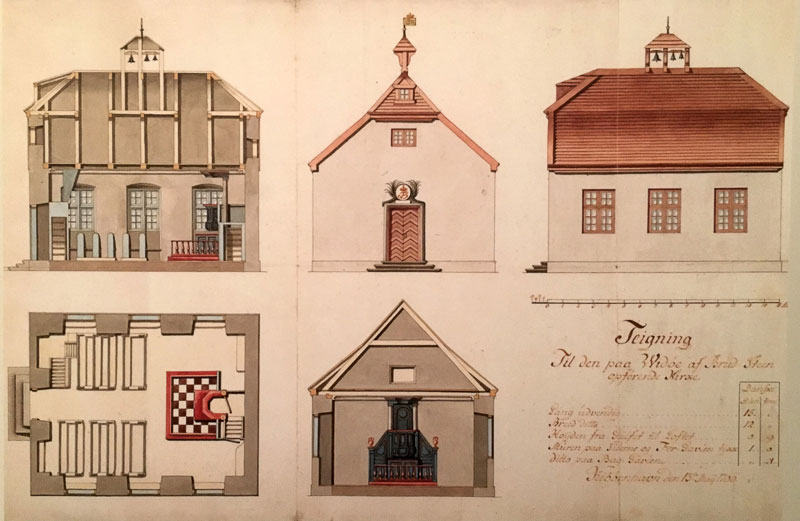

Figure 31. Elevations and a lateral section for the Viðey House. From the National Archives of Iceland.

Figure 32. Architectural drawings for the Viðey Church, dated 13 May 1766. From the National Archives of Iceland.

Viðey House was constructed for the Royal Treasurer Skúli Magnússon, commonly known as the Father of Reykjavík. Built between 1752 and 1755, it is one of the oldest surviving stone structures in Iceland. Driven by a didactic approach to architecture during the Enlightenment, the building was intended to serve as a model for new construction in Iceland, urging the locals to move away from turf building traditions and towards more permanent, masonry designs.8 Danish court architect Nicolai Eigtved (1701-1754) provided the plans for the building and, later, an unknown architect designed a church for the island that was constructed around 1774 (figures 31-32). The buildings have been restored several times, yet they do not seem to be the main draw for visitors to Viðey. Instead, visitors board the ferry for bird watching, biking, and inspection of two contemporary art installations: the Imagine Peace Tower by Yoko Ono and Áfangar [Milestones](1990) by Richard Serra, both visible in the aerial video below.

Figures 33–34. Photomontages by the author featuring the Parliament House and park along Kirkjustræti, combining photographs from 1900 and 2016.

The end of the 19th century, however, brought prosperity and new architectural developments. For Iceland, this was the era of Industrial Revolution where mechanization streamlined production and steam trawlers allowed for increased trade. The Parliament, built around 1881 became the first dressed stone building in Iceland and several other neoclassical masonry structures followed, although the trend did not last long (figures 33–34). Appointed by the newly empowered Home Rule government, architect Johannes Magdahl-Nielsen designed the National Library between 1906 and 1909 (figure 35).11 This would be the last major stone building in Reykjavik: with the introduction of concrete in 1900, the capital turned its attentions to this more industrious and malleable construction method for public buildings, as evidenced by the National Theatre of 1928 (figure 36). Nonetheless, the National Library, now known as the Culture House and home to a series of rotating and temporary exhibits, is a uniquely Icelandic building. It is comprised of a cavity wall with a Basalt exterior and concrete interior. Unfortunately, the exterior was covered with a slurry layer and painted white while the interior received stucco, entirely masking the masonry.

Figure 35. The distinctive façade of the Culture House stands out in Reykjavík due to its bright white coating and uncommon use of neoclassical forms.

Figure 36. Concrete rapidly replaced masonry structures in the 1920s and civic buildings, such as the National Theatre, were funded by public entertainment taxes.

Alongside the newfound prosperity and building boom initiated by Home Rule, a new class of wealthy citizens began building residences around the Tjörnin, in the areas known as Tjarnagata and Þingholtsstræti (figures 37–38). Many of these were influenced by the Swiss Chalet style and in 1906 the Craftsmen’s House was constructed for the Reykjavík Technical School.

Figure 37. A panoramic photograph looking north across the Tjörn. The Craftsmen’s house is the yellow structure in the center of the image.

Figure 38. Grettisgata 11 was home to one of Reykjavík’s master craftsmen, Jens Eyjólfsson.

Figure 39. ‘The Turnip’ was constructed as the retirement residence of Icelandic governor Magnús Stephensen in 1902.

With a new legion of trained builders with skills in concrete, corrugated metal, and wooden gingerbread work, structures like Fríkirkjuvegur 11 were now possible (figures 40–43). This home, designed by Einar Erlendsson between 1907 and 1908, contained the most modern advancements, such as plumbing and electricity, despite the fact that the city had yet to install public utilities. Entrepreneur-owner Thor Jensen capitalized on improved shipping routes and imported granite from Denmark to construct an impressive entry stairway and wood for a parquet floor. Although the project was under threat of demolition from the 1950s through the 1990s, a major renovation project is now underway and the building should reopen as offices for the City Council in late 2016. Although few homes were as grand as the one along Fríkirkjuvegur or ‘The Tulip’ (figure 39), metal-clad homes with wooden details dominated the residential architecture of the city in the early 20th century. With concrete substructures and metal weatherboard, the homes were economical and durable. Paint and wooden details also meant that even simple structures could be distinctive. The homes of the city’s artists, however, established different trends.

Figure 40. Photomontage by the author featuring the Fríkirkjuvegur.House and park near Tjörn, combining photographs from 1915 and 2016.

Figures 41–43. Details of the Fríkirkjuvegur 11, showing the use of wood, corrugated metal and faux finishes.

Figure 44. Photomontage by the author featuring the main façade of the Einar Jónsson Museum, combining photographs from c.1920 and 2016.

Figure 45. Jónsson and his wife in the snow-filled garden of their home, date unknown. From the online collection of the Einar Jónsson Museum.

Sculptor Einar Jónsson (1874–1954) was one of the first to establish this trend (figures 44–45). Trained at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and well traveled throughout Europe in the early 1900s, Jónsson donated all of his works to the nation in 1909 with the condition that the government provided an appropriate structure to house the collection. After parliament approved the request in 1914, State Architect Guðjón Samúelsson was commissioned for the project but Jónsson objected to the plans. Consequently, Jónsson intervened his own design ideas and enlisted the support of his friend and governmental architect Einar Erlendsson. The pair selected a site on the previously unbuilt Skolavorduhæd, described in the museum's interpretation as the 'Acropolis of an independent Iceland'. Opened in summer 1923 as Iceland’s first art museum, the Deco-inspired building with large, sculptural concrete forms also served as the sculptor’s studio, gallery, and home from 1920 until his death (figure 46). Eventually outgrowing the cramped quarters of the upper floor of the museum, Jónsson and his wife built a small home in the garden that provided easy access to the twenty-six bronze casts that would eventually dot the landscape, showcasing his signature interests in monumentality, personification, and the revival of classical sculpture (figure 47). The museum now holds more than 300 of the sculptor’s works, ranging from rough plaster maquettes to paintings and massive finished works.

Figure 46. Jónsson at work in his studio in Copehnagen, adding detail to a model of Þorfinnur Karlsefni, commissioned by the Fairmount Park Association and installed in Philadelphia in 1920. Photograph from the online collection of the Einar Jónsson Museum.

Figure 47. Photomontage by the author featuring the rear façade and sculpture garden of the Einar Jónsson Museum, combining photographs from 1920 and 2016.

Although initially spurned by Jónsson, Samúelsson’s architecture was certainly influenced by the sculptor. Eventually, Samúelsson would also build atop the Skolavorduhæd and it was here that he designed his masterpiece, the Hallgrimskirkja. Today, visitors can look down on Jónsson’s museum from the clock tower and this may have provided some form of amusement for Samúelsson, had he lived to see the completion of the church. Nonetheless, Jónsson’s use of geological forms within his sculptures can be seen as a precedent for the work of Samúelsson at the Hallgrimskirkja and the best possible evidence for this claim is Rest, a sculptural theme that Jónsson pursued at several scales and with different materials between 1915 and 1935 (figure 48). One of the plaster models now preserved in the museum presents a dynamic image of the head of a man emerging from basalt protrusions. The physical and allegorical layers of sculpture draw parallels to the Slaves series of Michelangelo, with figures that seem to emerge directly from the stone, rather than from the hand of the artist. The tower of the Hallgrimskirkja has prismatic basalt forms as buttresses, presenting the viewer with a façade that seems to grow from the natural summit of the Skolavorduhæd and reach, imposingly, towards the sky (figure 50). The highly textured exterior of Jónsson’s museum may have also influenced Samúelsson considering the architect began incorporating local aggregate into his roughcast from the mid-1920s. Examples can be seen throughout the city and the varied aggregate (obsidian, quartz, and spar) provides texture that breaks the visual monotony cast by even the grayest days while simultaneously acting as a reflective and luminescent surface under the sun’s rays.

Figure 48. A plaster iteration of Rest, housed on the museum’s ground floor. Photograph from the online collection of the Einar Jónsson Museum.

Figures 49–50. Views of the Hallgrimskirkja, featuring basalt-inspired crenellations and neo-gothic pointed arches. Many visitors mistakenly attribute the sculpture of Leif Eriksson (1930) to Jónsson but it was by American schulptor Alexander Stirling Calder.

The Ásmundarsafn is the common Icelandic name for the Ásmundur Sveinsson Sculpture Museum. Sveinsson (1893–1982) was a sculptor who, like Jónsson, was interested in the representation of Icelandic folklore and historical figures. Sveinsson’s subjects were often reduced to simplified forms that emphasized a particular action, akin to the work of Rodin or even elements of Botero, and several of his other pieces moved towards cubic abstraction.

Figures 51–52. Views of the Ásmundarsafn and its sculpture garden.

Like Jónsson’s home, the Ásmundarsafn works as a representative piece of sculpture for the works held within. Sveinsson designed the home in several stages, first constructing a two-story, domed building in 1942. Here, the family lived on the ground floor and Sveinsson used the top-lit upper floor as his studio (figure 55).13 He later worked with his friend and city architect Einar Sveinsson to design an Egyptian pylon-inspired entry, with flanking gallery spaces, and semi-circular studio on the site (figure 56).

Figures 53–54. Aerial views of the Ásmundarsafn.

Figure 55. The studio in its present form.

Figure 56. A maquette of the building, showing the layout before the connective joint was added in the late 1980s.

Figures 57–58. Photographs of the entrance galleries. One is now reserved for temporary exhibitions while the other represents Sveinsson’s studio.

Figures 59. A lamp designed and crafted by Sveinsson’s in the entrance corridor.

Figures 60–62. The rough exterior of the board-formed concrete used for the semi-circular addition conceals a bright, top-lit volume that was used as a studio and gallery.

In 1977, Sveinsson donated the home, studio, and works within to the city of Reykjavík and in preparation for opening the museum to the public, architect Manfreð Vilhjálmsson (b. 1928) designed an extension to connect the domed home to the studio in 1987 (figures 63–64).

Figures 63–64. The connective joint between the dome and the semi-circular addition creates a seamless transition between Sveinsson’s designs.

At the house museums of Jónsson and Sveinsson, I found myself alone in the galleries. This was spectacular for quiet exploration and uninterrupted photographs, especially in the Ásmundarsafn where certain spaces feel like you have stepped into an architectural rendering instead of a tangible space, but the absence of visitors was also a bit alarming considering the incredible content and spatial qualities of these museums. As recorded in visitor numbers from the tourist board, the summer is the busiest time of year for museums yet the halls were empty. The gardens, however, have been filled with locals each time I have visited the sites since the sculpture-filled green spaces are popular for picnics and games of hide and seek. Both sites had recent restorations and, perhaps, they are best left as local secrets?

Caption: Figures 65–66. Views of Þingvellir.

As previously noted, nature tourism dominates the agendas of visitors to Iceland and this has been the case since the first recorded foreign ‘tourists’ descended upon the island in the 18th century. Þingvellir [Thingvellir] National Park is one of two UNESCO World Heritage sites in Iceland and worth brief investigation in this assessment of key architectural sites in the region (figures 65–66.)14 Inscribed in 2004 in recognition of the rich historical landscape and unparalleled view of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the park is part of the manmade tourist circuit known as the Golden Circle.15 The other keys sites within the 300km circuit both deal with water. Gullfoss features an impressive cascade and the name instantly helps visitors learn a bit of Icelandic since gull means golden and foss means waterfall. The other site within the established triad of the Golden Circle is Geysir, the namesake for all other erupting hot springs. It has been active only once during the last century so, to the delight of visitors, the adjacent geyser known as Stokkur presents an impressive plume every few minutes.

Figure 67. Photomontage featuring the Þingvallær housing and Þingvallakirkja of Þingvellir National Park, combining photographs from the 1930 millenary celebration of the Alþing and 2016.

It is estimated the more than half of the visitors to Iceland partake in the Golden Circle, whether through guided tours or in hired cars.16 Cultural highlights of the park include The Alþingi, the island’s first general assembly, was established in 930 and served as the location of parliamentary procedures until 1798. Located along one of the main hiking trails, there are two noteworthy architectural sites: the Þingvallkirkja (figures 68–69), a church from 1859 that marks a site of worship that has been active since the 11th century, and a series of farmhouses built by Samúelsson in 1930 to house park staff and offices (figure 67).

Figures 68–69. Exterior and interior views of the traditional, wooden-framed Þingvallkirkja on the ground of the National Park.

As a side note, if anyone says that Iceland is a bug-free nation, they clearly have not visited the Þingvellir. The giant gnats are omnipresent. Nature photographers and explorers, too, are found in abundance due to the geological composition of the area, consisting of waterfalls, the largest lake in Iceland, and a continental rift. Since the park is popular for hikers and historians alike, visitors to Þingvellir have increased by 80% in the last decade.17

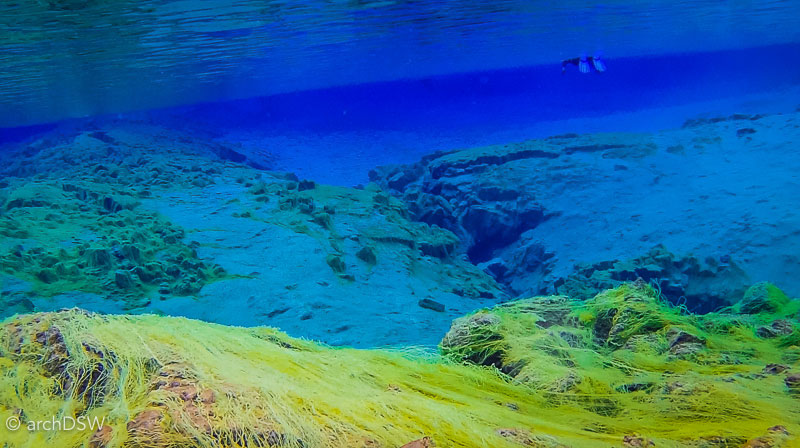

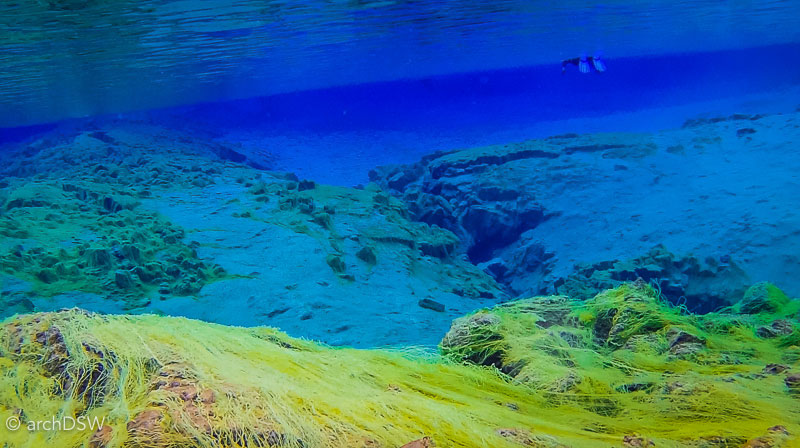

Caption: Figures 70–71. Underwater views of the Silfra fissure’s ‘cathedral’ and lagoon.

One of the most monumental elements of Þingvellir is the continental rift, representing movement between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. This rift is also causing Iceland to expand at a rate of two to three centimeters a year. Visitors can experience the rift on land at sites such as the continental bridge, or underwater at the Silfra Fissure where glacial ice melts from the Lángjökull provide crystal clear water and a smooth, steady current. Here, snorkelers and divers have the unparalleled opportunity explore a freshwater tectonic fissure, if they can brave the temperature: a refreshing 2°C/35°F throughout the year. Taking advantage of the opportunity for explore such a celebrated geological anomaly, I participated in a snorkeling excursion that I can describe as both surreal and, at times, quite claustrophobic. Aware of the influx of tourists and popularity of such eco-adventurers, the guides were keen to urge visitors to avoid touching or otherwise disturbing rocks of the fissure and similar natural sites since the careless actions of a few can eventually have disastrous impacts on whole ecosystems. As I watched countless people leave marked paths and stick lava rocks in their pockets during my two visits to the national park, I wondered if we have already reached that tipping point.

Figure 72–74. Although some of the buildings in the historic district met a dark fate, many others are being preserved.

Iceland capitalized on mobile technologies through the development of several apps catered to tourists, whether they are seeking hot pots [natural thermal baths], gas stations, or even happy hour venues around the capital. Therefore, it seems that the creation of an app could showcase the treasures of Iceland’s architectural history that are overlooked. For example, visitors frequently bypass preserved examples of Guðjón Samúelsson’s transformer stations from 1921 that were constructed as part of the supporting infrastructure for the groundbreaking hydroelectric facility along the Elliðaár River: by the second decade of the 20th century, Iceland was already going green (figure 75).18

Figure 75. One of the Baroque transformer stations in the Old Town.

Additionally, interactive architectural guides could give preservation success stories, as well as sites in desperate need of care, the consideration they deserve. By pairing the rich photographic record housed in the Reykjavík Museum of Photography with augmented reality technologies, visitors could turn their attention from Pokemon hunting to an app that reveals layered views of the capital city’s history and development, perhaps even showcasing projected renderings from the Reykjavík Municipal Plan 2010-2030 (figure 76).19 Such initiatives would be inline with the Municipal Plan that proposes densification and would help concentrate new tourist and preservation endeavors on urban areas, helping to alleviate some of the current stress on natural sites while they scramble to construct much-needed elements of infrastructure to ensure safety and sustainability.20 But for now, we just have to use our imaginations.

Figure 76. Photomontage by the author featuring the Hljómskálinn on Tjörn, combining photographs from 1925 and 2016.

Björnsson, Björn G. 18th Century Stone Buildings. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavík: Salka, 2013.

———. Large Turf Houses. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavík: Salka, 2013.

———. Turf Churches. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavík: Salka, 2013.

———. Writers' Homes. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavik: Salka, 2013.

ICOMOS. "Þingvellir National Park." Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee, March 2004.

IUCN. "Surtsey." World Heritage Nomination, April 2008.

Jóhannesson, Dennis. A Guide to Icelandic Architecture. Translated by Bernard Scudder. Edited by Jóhannesson Dennis Reykjavík: Association of Icelandic Architects, 2000.

Maack, Sigríður. "Can Reykjavík Stop the Sprawl? A Look at Reykjavík's New Municipal Plan for 2010-2030." HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 1 (2015): 42-49.

———. "One of the Largest Design Projects in Icelandic History." HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015): 40-47.

Þorleifsdóttir, Svava. "Growing Pains: Designing Travel Destinations in Iceland." HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015): 86-97.

1 See http://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2016/juni/tourism_-in_iceland_in_figures_may2016.pdf

2 Svava Þorleifsdóttir, "Growing Pains: Designing Travel Destinations in Iceland," HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015): 97.

3 Ibid., 90.

4 For more on the school see Dennis Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, ed. Jóhannesson Dennis, trans. Bernard Scudder (Reykjavík: Association of Icelandic Architects, 2000), 184.

5 Pétur H. Ármannsson, ""The Mountains Are Their Castles": Contemporary Architecture and Local Traditions in Iceland," in Iceland and Architecture?, ed. Peter Cachola Schmal (Frankfurt: Deutsches Architekturmuseum, 2011).

6 Ibid., 13.

7 Björn G. Björnsson, 18th Century Stone Buildings, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavík: Salka, 2013); Writers' Homes, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavik: Salka, 2013); Turf Churches, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavík: Salka, 2013); Large Turf Houses, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavík: Salka, 2013).

8 Ármannsson, ""The Mountains Are Their Castles": Contemporary Architecture and Local Traditions in Iceland," 15.

9 Björnsson, 18th Century Stone Buildings, 42.

10 Ármannsson, ""The Mountains Are Their Castles": Contemporary Architecture and Local Traditions in Iceland," 18.

11 Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, 69.

12 For more on this trend within the writing community see Björnsson, Writers' Homes.

13 Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, 109.

14 The other site is the volcanic island of Surtsey. For additional information, see IUCN, "Surtsey," (World Heritage Nomination, April 2008).

15 For additional information on the site, see the ICOMOS, "Þingvellir National Park," (Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee, March 2004).

16 Þorleifsdóttir, "Growing Pains: Designing Travel Destinations in Iceland."

17 Ibid., 91.

18 Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, 38.

19 Iceland’s first design and cultural journal, HA, frequently uses renderings to explore the impacts of new proposals. See Sigríður Maack, "One of the Largest Design Projects in Icelandic History," HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015).

20 For more information on the densification plans, see "Can Reykjavík Stop the Sprawl? A Look at Reykjavík's New Municipal Plan for 2010-2030," HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 1 (2015).

As I approach my sixth week of travels, I am enjoying a very welcome feeling of familiarity with Reykjavík and its environs. I have a favorite coffee shop, a preferred place to watch the late night sunsets that never disappoint, and the capital city’s parks are now animated with locals and visitors due to the recent ‘heat wave’. The crest of summer also welcomes a host of pop-up events around the city, ranging from a massive slip-n-slide on the steep shopping street of Laugavegur to a beer garden in the Old Town complete with transported turf to line the cobblestone streets. The days, however, are rapidly growing shorter: instead of the midnight sunset and 2 a.m. sunrise of the summer solstice, daylight lasts from about 4:30 a.m. until 10:30 p.m. and that light grows shorter by about ten minutes each day. Although the sunny hours are slipping away, studies from the Icelandic Board of Tourism prove that visitor numbers are nearing their peak for the year, at a little over half a million.1

Figure 1. Artificial light illuminating the buildings of Reykjavík Old Town in summertime.

Since 2013, tourism has been the main stream of revenue for the island. The majority of tourists state that ‘nature exploration’ is the main goal of their journey and in anticipation of the demands imposed by high visitor numbers to the islands, the Tourist Site Protection Fund was established in 2011.2 The Fund is currently working with 450 sites around the island, but their impacts have been limited due to the requirement that localities provide 50% of the funding for projects. As Iceland continues to promote ecotourism, local authorities are rushing to construct barriers for protecting tourists and natural resources alike: waterfalls, cliffs, and thermal fields pose dangers to curious visitors who wander from prescribed routes, site erosion runs rampant, and ecologists are carefully monitoring water and soil quality.

Figure 2. A sign at the Seltún thermal fields.

Through the Fund, officials hope to construct pathways, viewing platforms, and accessible routes that can be easily placed, and even removed, without large impacts on the natural sites.3 These interventions must sustain themselves with minimal maintenance, despite harsh climatic conditions, since the staff members of various parks and natural sites are already overtaxed. To fund so many built interventions, the government is currently evaluating the concept of a ‘nature pass’: a fee structure for all natural sites that would help support both necessary building initiatives and provide adequate staff.

Aerial view of the harbor skyline.

Curiously, as the island tries to inaugurate a massive do-no-harm building program for ecotourism, bringing essential way finding and landscape architecture interventions to frequently traversed sites, the island is doing fairly little to promote its architectural heritage or museums. These sites seem to fall to a second tier, at least from an advertising perspective, when compared to the Golden Circle, glacier walks, or even visits to the Blue Lagoon. Although one can find myriad walking tours around the capital, and many for free, the built environment is strangely absent from the offerings. There are tours that celebrate Reykjavík as a UNESCO City of Literature, ‘walking the crash’ from the banking fallout of 2008, pub crawls, culinary tours, and even an exploration of street art from the grassroots group I Heart Reykjavík, but there is not a tour primarily dedicated to the architecture and urban development of the city. In hopes of highlighting a few sites that can escape the typical visitor, this post will focus on some of the architectural gems of Iceland’s southwest and museums in the capital that provide an interesting glimpse into the island’s history through unique means of historical interpretation. Moving forward in partnership with Iceland’s new tourist initiatives, it will be critical that these architectural sites also receive the funding and attention needed to ensure their preservation.

Figure 3. A photomontage by the author of the Héraðsskólinn girls’ school, now a hostel, in Laugarvatn that combines photographs from 1936 and 2016. State architect Guðjón Samúelsson designed the school in 1928 and the roofline was intended to reference the region’s traditional domestic architecture: gabled turf farmhouses from the 18th and 19th centuries.4

Missing pieces

Before I journeyed to Iceland, I knew that I would not find any preserved structures from the Viking Age. However, as I continue explore Suðurland [the southwestern areas of the island] I am surprised that it is nearly impossible to find a piece of architecture from the 15th through the 18th centuries. The Suðurland is home to the oldest settlements and richest preserved architectural fabric, yet the oldest buildings in the capital region are from the later portion of the 1800s. There are a few examples where visitors can find earlier traces of Iceland’s built environment but these sites are not widely advertised. For example, there are a handful of sites with archaeological evidence of monasteries from the 1200s, such as the island of Viðey and Skálholt (figure 4). The latter, once home to the largest Catholic congregation and the bishop of Iceland, embodies the two main types of architectural heritage sites found in Iceland: vernacular structures, often reconstructions (figure 5), and striking examples of 20th-century modernism. Today, Skálholt is an auxiliary site for a handful of travelers on the Golden Circle who want the opportunity to imagine one of the many grand wooden cathedrals that occupied the site between the 11th century and the Reformation. Today, a small, honor-based fee system offers entry for those who want to duck through an earthen passage to the crypt, containing some of Iceland’s oldest Christian relics, and ascend into the colorful modern sanctuary (figures 6–7). However, the school and small restaurant dictate the majority of traffic to the site and only private tour companies offer excursions from the capital.

Figures 4–5. The Skálholt historical site, featuring a cathedral from the 1950s atop the ruins of a 12th-century monastery and a reconstructed turf-covered chapel.

Figure 6. A restored portion of the tunnel that once connected the medieval monastery to the adjacent school.

Figure 6. A restored portion of the tunnel that once connected the medieval monastery to the adjacent school.

Figure 7. A view of the nave of Skálholt church (1956-1963), with stained glass windows by Gerður Helgadóttir.

As explained by architectural historian Pétur H. Ármannsson in an essay entitled “The Mountains are Their Castles,” there are several reasons for the large gap of preserved structures within Iceland’s built record.5 The volcanic soil and porous lava rocks require alternative approaches to traditional stone building techniques and the production of brick is nearly impossible. Prior to settlement, approximately 25% of Iceland was forested but it is estimated that by the 12th century less than 2% of the island was wooded, putting a severe restriction on the use of wood for domestic or civic architecture. Complicating factors were the harsh climate as well as the tradition of rotating tenant farming in the 18th and 19th centuries: workers needed dwellings that could be constructed quickly with local materials and easily maintained in the harsh weather. Therefore, Icelanders turned to dense, turf-covered structures and used stretched Skate fish as translucent coverings for apertures in the roof. As buildings that literally combine the built and natural environments, Ármannsson recognizes these vernacular constructions as Iceland’s most important contribution to architectural history.6 However, with the exception of two living history museums, these structures are not part of the main cultural narrative presented to visitors to the island and it is difficult to trace Iceland’s architectural history within the nation’s established museums. Nonetheless, visitors who are willing to do some independent investigation can assemble the puzzle of Iceland’s architectural heritage by visiting several of the nation’s museums located both in and out of doors.

Of the five sites that comprise the Reykjavík City Museum [the Árbær Open Air Museum, The Settlement Exhibition, the Reykjavík Maritime Museum, the Reykjavík Museum of Photography, and Viðey Island], the majority feature interesting architecture but the interpretation of the sites focuses on other aspects of history.

Figure 8. A photograph from the Vikín Maritime Museum, illustrating Reykjavík’s harbor in 1910.

Figure 9. One of the permanent exhibitions in the museum focuses on the Cod Wars that occurred from the late 1950s to early 1970s as Iceland expanded its claim on the fishing territory around the island.

For example, the Vikín Maritime Museum (established 2005) is a recent adaptive reuse project that transformed a midcentury fish freezing plant into a site for interpreting the history of the harbor (figures 8–9). In hopes of creating a new path for understanding the architectural history of Iceland, this post will examine two sites within the Reykjavík City Museum, the Settlement Exhibition and Viðey Island, alongside several other natural site and cultural institutions.

Uncovering the layers of the city

As a small museum on the edge of the Old Town, the Settlement Exhibition tells the story of the Reykjavík’s foundation but the building's exterior does little to express the compelling architectural artifacts held within: the ruins of a 10th-century Viking longhouse that was discovered during a construction project along the Aðalstræti in 2001 (figures 10a and 10b). The nickname, Reykjavík +/- 2, prompts curious expressions from some visitors but for those acquainted with the history of the island it is a familiar equation referring to a significant geological event: the eruption of Torfajökull in 871, a date estimated within a two year margin of error. This event spread a layer of tephra around the island that is clearly marked within the horizon profile, helping archaeologists date a small portion of the longhouse preserved within the Settlement Exhibition to an era before 871. This makes the longhouse the oldest known structure in the city.

Figure 10. The unassuming entryway of the Settlement Exhibition does little to advertise the rich collections.

Figures 11–13. The ruins of a Viking longhouse, preserved within the subterranean Settlement Exhibition, exist a story beneath one of the Old Town’s main corners.

In addition to the unparalleled example of early architecture and vitrines around the perimeter of the room that hold relics and fragments discovered at the site, including bones of the now-extinct auk, the Settlement Exhibition is also home to some of the subtlest and most effective interactive installations I have ever seen within an interpretive exhibit design. The elliptical, subterranean exhibit surrounds the on-going archaeological excavations and the dim lighting provides ideal conditions for the backlit display boards. Here, ghostly silhouettes that hunt, fish, farm, and build enliven vibrantly colored representations of Reykjavík in the Viking era. The exhibits truly bring to life the 'smoky bay' and showcase how the city derived its name from steam plumes of nearby thermal springs. A touchscreen table allows visitors to explore the ongoing excavations at the longhouse while another screening room provides information on the materials and construction processes used by Viking builders. The museum is also home to manuscripts of the Sage Age, an era of the 12th when Icelandic writers recorded the oral histories of settlement, battles, and dramas of the initial settlement period from 870 to 930.

Animation of an early Icelandic inhabitant hunting a great auk now extinct, within the exhibition.

Figures 14–16. The illuminated and interactive displays of the Settlement Exhibition are put in stark contrast with the dimly lit ruins and utilitarian concrete posts and beams that support the subterranean space.

Figure 17. The stairway leading visitors back to the present-day level of Reykjavík.

Although entirely fascinating and perhaps one of the best exhibits for learning about how and why Reykjavík was settled, the subterranean museum receives fewer visitors than other sites. Like the Roman amphitheater discovered beneath the Guildhall in London or the Crypte archéologique du Parvis Notre-Dame, the Settlement Exhibition literally falls below the radar of many visitors but numbers have been bolstered by its inclusion on the Reykjavík Welcome Card, a tourist pass for access to various transit options and cultural sites.

The key site one would expect to find information on the built environment is the Þjóðminjasafn Íslands, the National Museum of Iceland. Although there are a handful of exhibits on traditional building techniques and a reconstruction of a baðstofa (figures 18–19), a typical one-room residence for much of Iceland’s rural population in the 19th century, the museum operates without an architectural curator. This is more incredible considering the museum serves as the steward for forty historic structures around the island.

Figure 18. The interior of the baðstofa illustrates the simple furnishings and build-in beds that were common in these dwellings. The single volume form helped concentrate heat during the colder temperatures of Iceland’s medieval period. Photograph captured in the National Museum of Iceland.

Figure 19. Various domestic accouterments from the late 18th and early 19th centuries, ranging from iron house keys decorative weather vanes bearing the family name of the occupants and date of construction. Photograph captured in the National Museum of Iceland.

Established in 1863, the National Museum of Iceland was originally housed in a series of public buildings in the Old Town. In 1945, State Architect Guðmundsson was charged with the design of a purpose-built museum, just outside of the city center along the Hringbraut ring road. Resembling a Werkbund factory more than a museum, the building features a series of chronological exhibitions rooms across three floors. With only a small section of one floor dedicated to the architecture of the island, visitors have to search a bit harder to understand the issues that facilitated transitions in construction and aesthetic principles. Leaving the museum, it is not clear how Iceland’s built environment evolved from turf-covered vernacular structures to neoclassical civic building to a capital city dominated by concrete. Local masterworks are unexplored and one of Reykjavík’s most prized architectural gems, just south of the National Museum amid the monumental early 20th-century institution structures of the University of Iceland, is not mentioned in the National Museum. This means that without some careful, prior research, architectural enthusiasts could miss the Nordic House that was designed by Alvar Aalto between 1963 and 1968 (figures20–29). It is home to a 30,000 volume library, small performance hall, and café for cultivating exchange between Iceland and other Scandinavian countries. Like the majority of his other projects, Aalto designed the hardware, furnishings, and lamps for the building. The unstained wood and the use of white paint throughout the building provide a neutral backdrop that makes natural light the main decorative feature of the building. The building’s exterior features the only bit of bold color: ceramic blue tiles line a portion of the roof and the sinuous line mimics the mountain range in the distance.

Figure 20–21. Views of and from the Nordic House emphasize the capital city’s dramatic landscape.

Figure 20–21. Original architectural drawings of the project hang within the building’s corridor.

Figure 24–29. Views of the interior of the Nordic House reveal several pieces of furniture and light fixtures designed by the architect.

It is in Aalto’s library that visitors can find some of the best resources for exploring Iceland’s architecture. Thankfully, the recent production of small guides and resource books help fill in the gaps about the nation’s architectural history. An architectural series by Björn Björnsson explores a few building types and some newly placed and state-sponsored signage helps tell the story of sites such as the Government House or Parliament.7 But to understand the transition from buildings made of turf to those constructed of stone, visitors have to venture to Viðey iIsland in Kollfjödur. The round-trip ferry ride to Viðey is part of the Reykjavík City Card and this tiny island, just a short ride from Reykjavik's old harbor, boasts a rich history (figure 30).

Figure 30. The view of Viðey Island from the Reykjavík harbor places the nation’s first stone structures within an impressive nature backdrop.

Figure 31. Elevations and a lateral section for the Viðey House. From the National Archives of Iceland.

Figure 32. Architectural drawings for the Viðey Church, dated 13 May 1766. From the National Archives of Iceland.

Viðey House was constructed for the Royal Treasurer Skúli Magnússon, commonly known as the Father of Reykjavík. Built between 1752 and 1755, it is one of the oldest surviving stone structures in Iceland. Driven by a didactic approach to architecture during the Enlightenment, the building was intended to serve as a model for new construction in Iceland, urging the locals to move away from turf building traditions and towards more permanent, masonry designs.8 Danish court architect Nicolai Eigtved (1701-1754) provided the plans for the building and, later, an unknown architect designed a church for the island that was constructed around 1774 (figures 31-32). The buildings have been restored several times, yet they do not seem to be the main draw for visitors to Viðey. Instead, visitors board the ferry for bird watching, biking, and inspection of two contemporary art installations: the Imagine Peace Tower by Yoko Ono and Áfangar [Milestones](1990) by Richard Serra, both visible in the aerial video below.

Videy aerial from Danielle Willkens on Vimeo.

Caption: Aerial footage of the architecture and art installations on Viðey Island.

Figures 33–34. Photomontages by the author featuring the Parliament House and park along Kirkjustræti, combining photographs from 1900 and 2016.

The end of the 19th century, however, brought prosperity and new architectural developments. For Iceland, this was the era of Industrial Revolution where mechanization streamlined production and steam trawlers allowed for increased trade. The Parliament, built around 1881 became the first dressed stone building in Iceland and several other neoclassical masonry structures followed, although the trend did not last long (figures 33–34). Appointed by the newly empowered Home Rule government, architect Johannes Magdahl-Nielsen designed the National Library between 1906 and 1909 (figure 35).11 This would be the last major stone building in Reykjavik: with the introduction of concrete in 1900, the capital turned its attentions to this more industrious and malleable construction method for public buildings, as evidenced by the National Theatre of 1928 (figure 36). Nonetheless, the National Library, now known as the Culture House and home to a series of rotating and temporary exhibits, is a uniquely Icelandic building. It is comprised of a cavity wall with a Basalt exterior and concrete interior. Unfortunately, the exterior was covered with a slurry layer and painted white while the interior received stucco, entirely masking the masonry.

Figure 35. The distinctive façade of the Culture House stands out in Reykjavík due to its bright white coating and uncommon use of neoclassical forms.

Figure 36. Concrete rapidly replaced masonry structures in the 1920s and civic buildings, such as the National Theatre, were funded by public entertainment taxes.

Alongside the newfound prosperity and building boom initiated by Home Rule, a new class of wealthy citizens began building residences around the Tjörnin, in the areas known as Tjarnagata and Þingholtsstræti (figures 37–38). Many of these were influenced by the Swiss Chalet style and in 1906 the Craftsmen’s House was constructed for the Reykjavík Technical School.

Figure 37. A panoramic photograph looking north across the Tjörn. The Craftsmen’s house is the yellow structure in the center of the image.

Figure 38. Grettisgata 11 was home to one of Reykjavík’s master craftsmen, Jens Eyjólfsson.

Figure 39. ‘The Turnip’ was constructed as the retirement residence of Icelandic governor Magnús Stephensen in 1902.

With a new legion of trained builders with skills in concrete, corrugated metal, and wooden gingerbread work, structures like Fríkirkjuvegur 11 were now possible (figures 40–43). This home, designed by Einar Erlendsson between 1907 and 1908, contained the most modern advancements, such as plumbing and electricity, despite the fact that the city had yet to install public utilities. Entrepreneur-owner Thor Jensen capitalized on improved shipping routes and imported granite from Denmark to construct an impressive entry stairway and wood for a parquet floor. Although the project was under threat of demolition from the 1950s through the 1990s, a major renovation project is now underway and the building should reopen as offices for the City Council in late 2016. Although few homes were as grand as the one along Fríkirkjuvegur or ‘The Tulip’ (figure 39), metal-clad homes with wooden details dominated the residential architecture of the city in the early 20th century. With concrete substructures and metal weatherboard, the homes were economical and durable. Paint and wooden details also meant that even simple structures could be distinctive. The homes of the city’s artists, however, established different trends.

Figure 40. Photomontage by the author featuring the Fríkirkjuvegur.House and park near Tjörn, combining photographs from 1915 and 2016.

Figures 41–43. Details of the Fríkirkjuvegur 11, showing the use of wood, corrugated metal and faux finishes.

Art and culture in the capital city

Of the many art museums in Reykjavík, the house museums and studios of two of Iceland’s most famous sculptors are of note. Based on my research and travels thus far, the Einar Jónsson Art Museum and the Ásmundarsafn are representative of a tradition in Iceland for poets and sculptors of the 20th century to construct their own creative and domestic retreats then bequeath these residences to the nation in hopes of preserving their work and adding to the record of cultural heritage.12

Figure 44. Photomontage by the author featuring the main façade of the Einar Jónsson Museum, combining photographs from c.1920 and 2016.

Figure 45. Jónsson and his wife in the snow-filled garden of their home, date unknown. From the online collection of the Einar Jónsson Museum.

Sculptor Einar Jónsson (1874–1954) was one of the first to establish this trend (figures 44–45). Trained at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and well traveled throughout Europe in the early 1900s, Jónsson donated all of his works to the nation in 1909 with the condition that the government provided an appropriate structure to house the collection. After parliament approved the request in 1914, State Architect Guðjón Samúelsson was commissioned for the project but Jónsson objected to the plans. Consequently, Jónsson intervened his own design ideas and enlisted the support of his friend and governmental architect Einar Erlendsson. The pair selected a site on the previously unbuilt Skolavorduhæd, described in the museum's interpretation as the 'Acropolis of an independent Iceland'. Opened in summer 1923 as Iceland’s first art museum, the Deco-inspired building with large, sculptural concrete forms also served as the sculptor’s studio, gallery, and home from 1920 until his death (figure 46). Eventually outgrowing the cramped quarters of the upper floor of the museum, Jónsson and his wife built a small home in the garden that provided easy access to the twenty-six bronze casts that would eventually dot the landscape, showcasing his signature interests in monumentality, personification, and the revival of classical sculpture (figure 47). The museum now holds more than 300 of the sculptor’s works, ranging from rough plaster maquettes to paintings and massive finished works.

Figure 46. Jónsson at work in his studio in Copehnagen, adding detail to a model of Þorfinnur Karlsefni, commissioned by the Fairmount Park Association and installed in Philadelphia in 1920. Photograph from the online collection of the Einar Jónsson Museum.

Figure 47. Photomontage by the author featuring the rear façade and sculpture garden of the Einar Jónsson Museum, combining photographs from 1920 and 2016.

Although initially spurned by Jónsson, Samúelsson’s architecture was certainly influenced by the sculptor. Eventually, Samúelsson would also build atop the Skolavorduhæd and it was here that he designed his masterpiece, the Hallgrimskirkja. Today, visitors can look down on Jónsson’s museum from the clock tower and this may have provided some form of amusement for Samúelsson, had he lived to see the completion of the church. Nonetheless, Jónsson’s use of geological forms within his sculptures can be seen as a precedent for the work of Samúelsson at the Hallgrimskirkja and the best possible evidence for this claim is Rest, a sculptural theme that Jónsson pursued at several scales and with different materials between 1915 and 1935 (figure 48). One of the plaster models now preserved in the museum presents a dynamic image of the head of a man emerging from basalt protrusions. The physical and allegorical layers of sculpture draw parallels to the Slaves series of Michelangelo, with figures that seem to emerge directly from the stone, rather than from the hand of the artist. The tower of the Hallgrimskirkja has prismatic basalt forms as buttresses, presenting the viewer with a façade that seems to grow from the natural summit of the Skolavorduhæd and reach, imposingly, towards the sky (figure 50). The highly textured exterior of Jónsson’s museum may have also influenced Samúelsson considering the architect began incorporating local aggregate into his roughcast from the mid-1920s. Examples can be seen throughout the city and the varied aggregate (obsidian, quartz, and spar) provides texture that breaks the visual monotony cast by even the grayest days while simultaneously acting as a reflective and luminescent surface under the sun’s rays.

Figure 48. A plaster iteration of Rest, housed on the museum’s ground floor. Photograph from the online collection of the Einar Jónsson Museum.

Figures 49–50. Views of the Hallgrimskirkja, featuring basalt-inspired crenellations and neo-gothic pointed arches. Many visitors mistakenly attribute the sculpture of Leif Eriksson (1930) to Jónsson but it was by American schulptor Alexander Stirling Calder.

The Ásmundarsafn is the common Icelandic name for the Ásmundur Sveinsson Sculpture Museum. Sveinsson (1893–1982) was a sculptor who, like Jónsson, was interested in the representation of Icelandic folklore and historical figures. Sveinsson’s subjects were often reduced to simplified forms that emphasized a particular action, akin to the work of Rodin or even elements of Botero, and several of his other pieces moved towards cubic abstraction.

Figures 51–52. Views of the Ásmundarsafn and its sculpture garden.

Like Jónsson’s home, the Ásmundarsafn works as a representative piece of sculpture for the works held within. Sveinsson designed the home in several stages, first constructing a two-story, domed building in 1942. Here, the family lived on the ground floor and Sveinsson used the top-lit upper floor as his studio (figure 55).13 He later worked with his friend and city architect Einar Sveinsson to design an Egyptian pylon-inspired entry, with flanking gallery spaces, and semi-circular studio on the site (figure 56).

Figures 53–54. Aerial views of the Ásmundarsafn.

Figure 55. The studio in its present form.

Figure 56. A maquette of the building, showing the layout before the connective joint was added in the late 1980s.

Figures 57–58. Photographs of the entrance galleries. One is now reserved for temporary exhibitions while the other represents Sveinsson’s studio.

Figures 59. A lamp designed and crafted by Sveinsson’s in the entrance corridor.

Figures 60–62. The rough exterior of the board-formed concrete used for the semi-circular addition conceals a bright, top-lit volume that was used as a studio and gallery.

In 1977, Sveinsson donated the home, studio, and works within to the city of Reykjavík and in preparation for opening the museum to the public, architect Manfreð Vilhjálmsson (b. 1928) designed an extension to connect the domed home to the studio in 1987 (figures 63–64).

Figures 63–64. The connective joint between the dome and the semi-circular addition creates a seamless transition between Sveinsson’s designs.

At the house museums of Jónsson and Sveinsson, I found myself alone in the galleries. This was spectacular for quiet exploration and uninterrupted photographs, especially in the Ásmundarsafn where certain spaces feel like you have stepped into an architectural rendering instead of a tangible space, but the absence of visitors was also a bit alarming considering the incredible content and spatial qualities of these museums. As recorded in visitor numbers from the tourist board, the summer is the busiest time of year for museums yet the halls were empty. The gardens, however, have been filled with locals each time I have visited the sites since the sculpture-filled green spaces are popular for picnics and games of hide and seek. Both sites had recent restorations and, perhaps, they are best left as local secrets?

Exploring historic landscapes

Caption: Figures 65–66. Views of Þingvellir.

As previously noted, nature tourism dominates the agendas of visitors to Iceland and this has been the case since the first recorded foreign ‘tourists’ descended upon the island in the 18th century. Þingvellir [Thingvellir] National Park is one of two UNESCO World Heritage sites in Iceland and worth brief investigation in this assessment of key architectural sites in the region (figures 65–66.)14 Inscribed in 2004 in recognition of the rich historical landscape and unparalleled view of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the park is part of the manmade tourist circuit known as the Golden Circle.15 The other keys sites within the 300km circuit both deal with water. Gullfoss features an impressive cascade and the name instantly helps visitors learn a bit of Icelandic since gull means golden and foss means waterfall. The other site within the established triad of the Golden Circle is Geysir, the namesake for all other erupting hot springs. It has been active only once during the last century so, to the delight of visitors, the adjacent geyser known as Stokkur presents an impressive plume every few minutes.

Figure 67. Photomontage featuring the Þingvallær housing and Þingvallakirkja of Þingvellir National Park, combining photographs from the 1930 millenary celebration of the Alþing and 2016.

It is estimated the more than half of the visitors to Iceland partake in the Golden Circle, whether through guided tours or in hired cars.16 Cultural highlights of the park include The Alþingi, the island’s first general assembly, was established in 930 and served as the location of parliamentary procedures until 1798. Located along one of the main hiking trails, there are two noteworthy architectural sites: the Þingvallkirkja (figures 68–69), a church from 1859 that marks a site of worship that has been active since the 11th century, and a series of farmhouses built by Samúelsson in 1930 to house park staff and offices (figure 67).

Figures 68–69. Exterior and interior views of the traditional, wooden-framed Þingvallkirkja on the ground of the National Park.

As a side note, if anyone says that Iceland is a bug-free nation, they clearly have not visited the Þingvellir. The giant gnats are omnipresent. Nature photographers and explorers, too, are found in abundance due to the geological composition of the area, consisting of waterfalls, the largest lake in Iceland, and a continental rift. Since the park is popular for hikers and historians alike, visitors to Þingvellir have increased by 80% in the last decade.17

Caption: Figures 70–71. Underwater views of the Silfra fissure’s ‘cathedral’ and lagoon.

One of the most monumental elements of Þingvellir is the continental rift, representing movement between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. This rift is also causing Iceland to expand at a rate of two to three centimeters a year. Visitors can experience the rift on land at sites such as the continental bridge, or underwater at the Silfra Fissure where glacial ice melts from the Lángjökull provide crystal clear water and a smooth, steady current. Here, snorkelers and divers have the unparalleled opportunity explore a freshwater tectonic fissure, if they can brave the temperature: a refreshing 2°C/35°F throughout the year. Taking advantage of the opportunity for explore such a celebrated geological anomaly, I participated in a snorkeling excursion that I can describe as both surreal and, at times, quite claustrophobic. Aware of the influx of tourists and popularity of such eco-adventurers, the guides were keen to urge visitors to avoid touching or otherwise disturbing rocks of the fissure and similar natural sites since the careless actions of a few can eventually have disastrous impacts on whole ecosystems. As I watched countless people leave marked paths and stick lava rocks in their pockets during my two visits to the national park, I wondered if we have already reached that tipping point.

Lingering questions

At the present moment, the capital city and surrounding areas of the Suðurland make little of the preserved architectural heritage and offer few opportunities for visitors to learn about significant structures and movements. However, it is clear that changes are in the works. Despite the fact that some historic homes are collapsing beneath the cranes constructing the city’s new skyline, there are many others covered in wooden scaffolding, undergoing careful restoration (figures 72–74). Museums are well organized and have extended operating hours in the summer while public art initiatives are expanding around the nation.

Figure 72–74. Although some of the buildings in the historic district met a dark fate, many others are being preserved.

Iceland capitalized on mobile technologies through the development of several apps catered to tourists, whether they are seeking hot pots [natural thermal baths], gas stations, or even happy hour venues around the capital. Therefore, it seems that the creation of an app could showcase the treasures of Iceland’s architectural history that are overlooked. For example, visitors frequently bypass preserved examples of Guðjón Samúelsson’s transformer stations from 1921 that were constructed as part of the supporting infrastructure for the groundbreaking hydroelectric facility along the Elliðaár River: by the second decade of the 20th century, Iceland was already going green (figure 75).18

Figure 75. One of the Baroque transformer stations in the Old Town.

Additionally, interactive architectural guides could give preservation success stories, as well as sites in desperate need of care, the consideration they deserve. By pairing the rich photographic record housed in the Reykjavík Museum of Photography with augmented reality technologies, visitors could turn their attention from Pokemon hunting to an app that reveals layered views of the capital city’s history and development, perhaps even showcasing projected renderings from the Reykjavík Municipal Plan 2010-2030 (figure 76).19 Such initiatives would be inline with the Municipal Plan that proposes densification and would help concentrate new tourist and preservation endeavors on urban areas, helping to alleviate some of the current stress on natural sites while they scramble to construct much-needed elements of infrastructure to ensure safety and sustainability.20 But for now, we just have to use our imaginations.

Figure 76. Photomontage by the author featuring the Hljómskálinn on Tjörn, combining photographs from 1925 and 2016.

References

Ármannsson, Pétur H. ""The Mountains Are Their Castles": Contemporary Architecture and Local Traditions in Iceland." In Iceland and Architecture?, edited by Peter Cachola Schmal, 11-45. Frankfurt: Deutsches Architekturmuseum, 2011.Björnsson, Björn G. 18th Century Stone Buildings. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavík: Salka, 2013.

———. Large Turf Houses. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavík: Salka, 2013.

———. Turf Churches. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavík: Salka, 2013.

———. Writers' Homes. Translated by Anna Yates. Reykjavik: Salka, 2013.

ICOMOS. "Þingvellir National Park." Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee, March 2004.

IUCN. "Surtsey." World Heritage Nomination, April 2008.

Jóhannesson, Dennis. A Guide to Icelandic Architecture. Translated by Bernard Scudder. Edited by Jóhannesson Dennis Reykjavík: Association of Icelandic Architects, 2000.

Maack, Sigríður. "Can Reykjavík Stop the Sprawl? A Look at Reykjavík's New Municipal Plan for 2010-2030." HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 1 (2015): 42-49.

———. "One of the Largest Design Projects in Icelandic History." HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015): 40-47.

Þorleifsdóttir, Svava. "Growing Pains: Designing Travel Destinations in Iceland." HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015): 86-97.

1 See http://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2016/juni/tourism_-in_iceland_in_figures_may2016.pdf

2 Svava Þorleifsdóttir, "Growing Pains: Designing Travel Destinations in Iceland," HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015): 97.

3 Ibid., 90.

4 For more on the school see Dennis Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, ed. Jóhannesson Dennis, trans. Bernard Scudder (Reykjavík: Association of Icelandic Architects, 2000), 184.

5 Pétur H. Ármannsson, ""The Mountains Are Their Castles": Contemporary Architecture and Local Traditions in Iceland," in Iceland and Architecture?, ed. Peter Cachola Schmal (Frankfurt: Deutsches Architekturmuseum, 2011).

6 Ibid., 13.

7 Björn G. Björnsson, 18th Century Stone Buildings, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavík: Salka, 2013); Writers' Homes, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavik: Salka, 2013); Turf Churches, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavík: Salka, 2013); Large Turf Houses, trans. Anna Yates (Reykjavík: Salka, 2013).

8 Ármannsson, ""The Mountains Are Their Castles": Contemporary Architecture and Local Traditions in Iceland," 15.

9 Björnsson, 18th Century Stone Buildings, 42.

10 Ármannsson, ""The Mountains Are Their Castles": Contemporary Architecture and Local Traditions in Iceland," 18.

11 Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, 69.

12 For more on this trend within the writing community see Björnsson, Writers' Homes.

13 Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, 109.

14 The other site is the volcanic island of Surtsey. For additional information, see IUCN, "Surtsey," (World Heritage Nomination, April 2008).

15 For additional information on the site, see the ICOMOS, "Þingvellir National Park," (Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee, March 2004).

16 Þorleifsdóttir, "Growing Pains: Designing Travel Destinations in Iceland."

17 Ibid., 91.

18 Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, 38.

19 Iceland’s first design and cultural journal, HA, frequently uses renderings to explore the impacts of new proposals. See Sigríður Maack, "One of the Largest Design Projects in Icelandic History," HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 2 (2015).

20 For more information on the densification plans, see "Can Reykjavík Stop the Sprawl? A Look at Reykjavík's New Municipal Plan for 2010-2030," HA: Hönnun & arkitektúr á Ísland [Design & architecture in Iceland] 1 (2015).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top